September 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung, your very own vehicle to the marvels of ancient Tibet! This month’s offering is filled with the third and final part of an article about wild yak hunting in the rock art of uppermost Tibet. If you have not already done so, it is suggested that readers begin with the first part of the article in the July newsletter.

Bravery, Propitiation and Accomplishment: Wild yak hunting in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 3

Note: For the first and second parts of this article, see the July and August newsletters. For the bibliography, see the July newsletter.

Part 3 of this article is divided into the following subsections:

The group hunting of wild yaks and associated activities in the Iron Age

The group hunting of wild yaks and associated activities in the Protohistoric period

Interspecies hunting

Horsemen and other human figures and wild yaks in various non-killing scenes

Chronological terminology used in this work:

Late Bronze Age: ca. 1500–700 BCE (differentiation between late Bronze Age and early Iron Age omitted due to lack of data)

Iron Age: ca. 700–100 BCE

Protohistoric period: ca. 100 CE to 650 CE

Early Historic period: ca. 650–1000 CE

The group hunting of wild yaks and associated activities in the Iron Age

Part 3 begins with rock art scenes in Upper Tibet depicting two or more archers hunting wild yaks together. Most of these archers are mounted but sometimes horsemen are shown working in tandem with bowmen on foot. The physical challenge, whirlwind of activity and drama incumbent in wild yak hunting is amply demonstrated in this genre of rock art. A high degree of cooperation and tactical skill is implicit in scenes involving multiple players. The group hunting of wild yaks also reveals a particular set of social functions characterized by affiliation, leadership and prestige (see Part 1 for discussion).

The chronological division of wild yak hunting rock art into the Iron Age and Protohistoric period is based on criteria enumerated in Part 1 of this article. This categorization of rock art according to age constitutes a subjective appraisal and is open to amendment should new findings make that necessary.

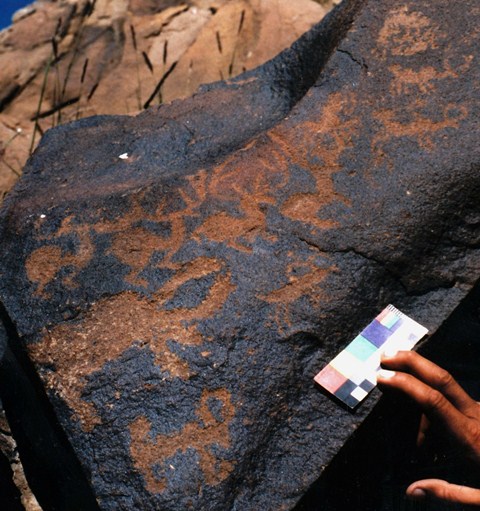

Fig. 50. Three wild yaks, several other wild ungulates, standing archer and what appears to be another anthropomorph (figure in human form) with long-tailed animal, far western Tibet. Most figures belong to the Iron Age.

This appears to be a hunting scene but one with additional dimensions of meaning or pictorial narration amended to it. On the bottom left side of the boulder, a pair of wild yaks face in opposite directions. The elongated animal below the two wild yaks may possibly be a stag (more clearly rendered stags in this style are found at the same site). The two central anthropomorphic figures are flanked by wild yaks. The more finely carved bowman and carnivore to his left and wild caprid to his right seem to form a separate composition. The carnivore appears to be a hunting dog belonging to the standing archer, who aims in the direction of the wild caprid situated at a considerable distance away. The anthropomorph to the left of the ostensible hound was executed in a different style.

Fig. 51. Close-up of central figures in fig. 50.

In this photograph, the different carving techniques employed to produce the two anthropomorphic figures are clearly recognizable. The anthropomorph on the left may be holding objects in his hands. The archer appears to be attired in a long robe. His bow and the arm grasping it form a cross-shaped pattern. The arrowhead is pointing in the direction of the wild caprid (not shown). The bowman’s other arm reaches out towards what appears to be his hunting dog. This bowman, carnivore and wild caprid composition may possibly predate the introduction of the riding horse in Upper Tibet. If so, they can be attributed to the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age.

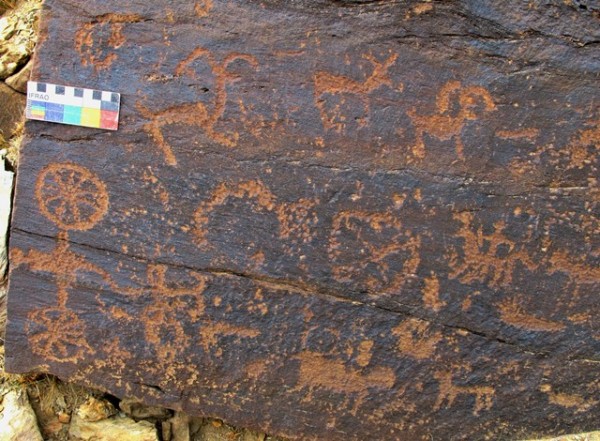

Fig. 52. Three wild yaks (middle part of image), three horsemen (bottom right), ostensible carnivore with gaping jaws and another quadruped (left side), far western Tibet. Iron Age. Below the horsemen is a double volute motif.

The compositional organization of figures on this boulder has not been determined.* The petroglyphs constitute two or more separate compositions. The larger horseman on the extreme right side may have been carved by a different hand than the other two. The horsemen are not armed with bows so it is not certain that they are hunters. However, the carnivore and wild yaks appear to convey the predator-prey cycle. The double volute motif is a Eurasian animal style trait, prominent in the rock art of northwestern Tibet.

For this rock art, also see Bellezza 2002a, pp. 141, 235 (fig. XI-2f).

Fig. 53. The two largest figures on the panel are wild yaks, the lower one of which is being attacked by a standing archer, far western Tibet. Iron Age. Below the lower wild yak is what may be an equid (horse or wild ass) carrying something on its back. At the bottom of the boulder there is another standing archer. Higher up on the boulder there are at least four other wild ungulates.

The two standing archers and most other figures on this boulder may possibly predate the introduction of the riding horse in Upper Tibet.* In any case, the face to face encounter of a standing archer with a wild yak only occurs in the earliest phases of Upper Tibetan rock art. The depiction of this risky hunting technique is uncommon in the rock art of the region.

For this boulder, also see ibid., pp. 141, 236 (fig. XI-4f).

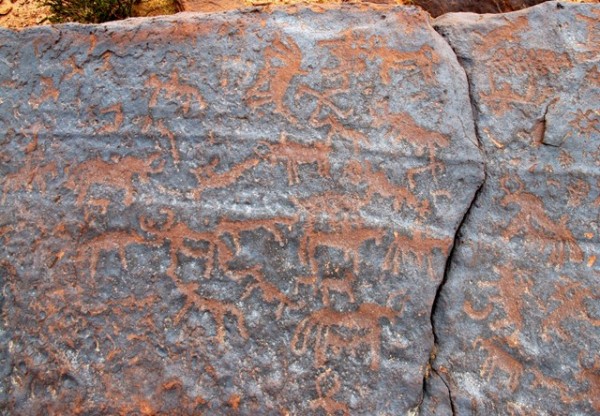

Fig. 54. A complex hunting scene consisting of two or more independently made compositions, far western Tibet. Iron Age. The figures include a standing archer attacking a wild yak (top left). There are no less than seven other wild yaks depicted. A triangular subject (upper middle) and circular subject (middle right) may possibly represent hunting traps or barriers. The boulder sports four mounted archers assailing wild yaks (bottom half). There are also several smaller zoomorphic figures interspersed across the face of the boulder.

The standing archer at the top of the boulder wears a knee-length robe. The mounted archers are working in concert to kill wild yaks. They drive their prey towards the center of the scene.* Although the hunters do not fully encircle their prey, they are outflanking wild yaks, essential in gaining a tactical advantage over them.

For this rock art, also see ibid., pp. 141, 237 (fig. XI-5f).

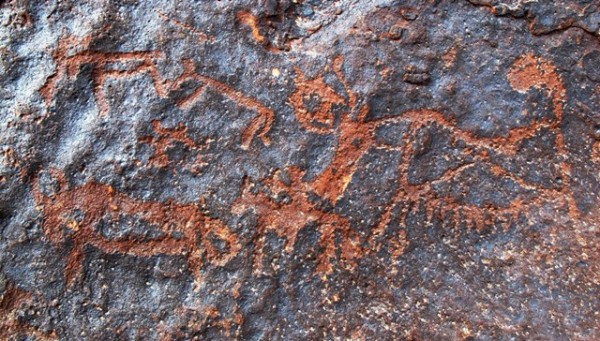

Fig. 55. Close-up of two mounted archers on right side of boulder illustrated in fig. 54.

The wild yak between the two hunters appears to be running at high speed, its rear legs thrown up in the air. A projectile appears to be lodged in the back of the animal. Above it, a wild yak or some other species of wild herbivore appears to be entering a circular trap or enclosure.

It is not clear how many of the mounted archers belong to the same composition as the stricken wild yak. These pictographs are part of a densely packed mass of cave paintings that cannot be parsed easily into individual compositions, as there is so much thematic and stylistic overlap. The wild yak has been struck in the haunches by one or two arrows, a clarion sign that the hunt has been successful. The swept back tail of the wild yak suggests that it is depicted running at full speed. The lowermost horseman painted in yellow ochre has a forked headdress reminiscent of feathers, and the mane of his horse is portrayed in a series of barbed lines. The mythic horned eagle (khyung) in yellow ochre appears to stand on its own.

Fig. 57. A boulder with disparate figures, western Changthang. Iron Age. Figures comprising various compositions include what appear to be three horsemen, wild yak, another animal, sun, and crescent moon (top of boulder), tree and wild yak (left side), horned eagle and standing bird (bottom right), wild yak and swastika (bottom left), and unidentified subjects (middle and middle bottom).

It is not certain in which activity the horsemen are engaged. They may be hunting wild yaks but the carvings on this boulder comprise far more than that. The tree, sun, moon and horned eagle are seminal figures and symbols in Tibet, which during the historical era have encapsulated a wide range of cosmological, mythic and religious ideas. As this boulder demonstrates, the equestrian arts and wild yaks were closely tied to these fundamental cultural motifs in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 58. Two mounted archers, wild yak and hunting dog, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The wild yak is under attack by one or both mounted archers. The dog appears to be biting the snout of the wild yak, an action that would draw the prey’s attention away from the hunters who are closing in on it from two other directions. The wild yak may have already been hit by an arrow in the back of the neck.

Fig. 59. One bowman on foot and one bowman on horseback slaying two wild yaks, western Changthang. Iron Age.

Here we have an example of a standing archer and mounted archer working in concert. An arrow is lodged in the back of the wild yak on the left. The yak on the right may also have been hit by an arrow that bisects its body.

Fig. 60. Wild yak, two other animals, two standing human figures, and unidentified subject at bottom of rock panel, far western Tibet. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Perhaps this rock art forms two different compositions and probably includes a hunting scene. The upper human figure appears to brandish a bow and perhaps has an arrow in his other hand. In addition to the unambiguously rendered wild yak there are two other wild herbivores on the rock panel.

Fig. 61. Five mounted archers (the uppermost one is partially cut in the photograph) almost encircling two or more wild yaks, and other animals, western Changthang. Iron Age.

On the lower left side of the image a hunting dog springs up at a wild yak. There may be one or two more hunting dogs depicted in this integral composition, but they are presented in an indistinct manner.

Fig. 62. Partial view of a boulder with a complex hunting scene, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The carvings on this boulder were made by different hands. On this boulder there are over seventy figures of mounted hunters, wild yaks, wild caprids, carnivores, raptor, sunbursts, crescent moons, tree, linear subjects, etc. On the left side of the rock, four or five long-tailed carnivores are savaging a wild yak. They may be either hunting hounds or wild animals. All around this part of the scene mounted archers are attacking wild yaks. On the upper right side of the image are three sunbursts (one is partly cut) and on the lower right side there is a wild caprid and crescent moon. Also note the two swastika-like subjects (upper middle and middle right).

Fig. 63. Upper right side of same boulder face in fig. 62.

On this part of the boulder there are men on horseback with bows or other instruments, tree, sunbursts, wild yaks, and other animals. Note the striped animal (oriented vertically) at the top of the boulder. This may possibly represent a tiger, a species known from a number of rock art sites in Upper Tibet. Hunting notwithstanding this group of carvings highlights a symbolic vocabulary pregnant with cultural meaning.

Fig. 64. Close-up of middle right portion of boulder face illustrated in fig. 63.

It is not certain what kind of object the horseman is holding up. The wild yak above is nearly upon him. Perhaps ritual practices are implicit in such a scene.

Fig. 65. Close-up of middle of boulder face illustrated in fig. 63.

The horseman grasps an unidentified object (drum or mirror come to mind). To the left there is a sun with eight rays.

Fig. 66. Part of same boulder illustrated in fig. 62.

On this portion of the boulder there is an archer on horseback between two wild yaks. The body of the wild yak on the right combines an hourglass and triangle. What appears to be a sunburst is carved between its horns (which flare out at the ends). Above the wild yak on the left a long-tailed carnivore is pursuing a wild herbivore. Below these two animals is an unfinished sunburst.

Fig. 67. Part of a complex hunting scene consisting of more than 30 figures, dominated by archers attacking wild yaks, western Changthang. Iron Age.

On this part of the boulder there are three mounted archers shooting at five or six wild yaks. On the right edge of the boulder is what appears to be a standing archer. On the upper right side is what may possibly be another horse but if there is a rider it is extremely attenuated. On the bottom third of the boulder there are two or three other animals. Curvilinear subjects near the top of the boulder have not been identified.

Fig. 68. Three horsemen (two of them clearly have bows) attacking two wild yaks, western Changthang. Iron Age.

There is an unidentified figure immediately to the left of the seemingly unarmed horseman on the upper right side of the image.

Fig. 69. Three wild yaks and one to three mounted archers, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The mounted archer the right is explicitly shooting at the wild yak in front of him. There is a wild yak in a different style below these two figures. This lowermost wild yak on the boulder may also be confronting a mounted archer but the carving is obscure. On the left side of the boulder the horns of a wild yak nearly touch what appears to be the horse of another rider. The import of this part of the composition is not readily discernable.

Fig. 70. Complex scene covering most of the boulder, consisting of five wild yaks, three horsemen (at least one of which is shooting an arrow) and standing archer, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The mounted archer in the middle left of the boulder is accompanied by a hunting dog. All the wild yaks appear to have been hit in the back with arrows. On the upper right side of the boulder is another hunting composition consisting of an archer on horseback attacking a wild yak (carved in outline). A yak from the larger composition is interposed between these two more re-patinated figures. On the lower right side of the rock a standing archer shoots at the belly of a wild yak.

Fig. 71. Close-up of a wild yak impaled by the arrows of a hunter and horseman illustrated in fig. 70.

The wild yak has three projectiles sticking out of its neck and body. The hunter is shooting another arrow, probably depicting the final act of killing.

Fig. 72. The right side of the boulder illustrated in fig. 70.

The two different scenes on this section of the boulder can be seen in the photograph. The more re-patinated composition (upper right side) consists of a wild yak with a multi-branched sinuous line of uncertain identity connected to it, a half circle (possibly a trap) and a mounted archer to the left. A wild yak belonging to a larger composition stands between the horseman and his quarry. On the bottom left side of the image is a standing archer aiming at the belly of a wild yak. This aspect seems to signify that the archer was lying in wait for his prey, permitting an attack from a highly advantageous position.

Fig. 73. Two mounted archers and doomed wild yak, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The upper archer is releasing an arrow in the direction of the wild yak, which has already been hit by one or two arrows that deeply pierce its body. It is not clear what the lower archer is shooting at. In between him and the wild yak is the carving of what might be another animal.

Fig. 74. A dense array of around 20 figures of wild yaks, wild caprids, mounted archers and possibly a hunting hound on a boulder, western Changthang. Iron Age.

The various animal carvings are more or less organized in rows. The wild caprids (horns curling downward) are situated in a middle row, an archer in the upper row, and wild yaks in the upper and lower rows and on the right side of the boulder. Another horseman composition is located higher up on the boulder.

Fig. 75. Close-up of mounted archer and wild yak prey in fig. 74.

The archer (his legs hang below the belly of the horse) is facing backwards as he shoots at the wild yak, in a special display of martial ability and equestrian skill.

The group hunting of wild yaks and associated activities in the Protohistoric period

Fig. 76. Mounted archer firing upon wild yak, and standing anthropomorph, eastern Changthang. Protohistoric period.

The horseman is bearing down on the wild yak as he fires his arrow. It appears that his prey has already been hit in the back by a number of arrows. The action of the standing human figure is in question. Perhaps he is lassoing the horns of the wild yak but this hardly seems practicable given the great power of the animal. Perhaps a wild yak could be distracted in this manner, making it more vulnerable to archers. Another possible interpretation is that this anthropomorph is a supernatural figure such as a guardian of the hunt. What might be the cantle and pommel of the hunter’s saddle are visible. The taller wedge-shaped object on the rear of the horse has not been identified.*

On this rock art, also see Bellezza 2002b, p. 366 (fig. 10).

Fig. 77. Three mounted archers coursing three wild yaks. A fourth horseman (middle right) may possibly be a part of the same scene. Above this composition standing archers are hunting wild caprids (partly visible in image), far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

On this one rock face two major modes of hunting in ancient Upper Tibet are presented: wild yak hunting by horsemen and wild caprid hunting by archers on foot.* Two of the wild yaks carry body ornamentation (two dots, double volute) characteristic of the Eurasian animal style in Upper Tibet. This genre of art persisted in Tibet as a relict cultural trait until modern times.

On this rock art, also see Bellezza 2002a, p. 176 (fig. 313).

Fig. 78. On this rock panel there are seven well represented wild yaks, several other animals and unidentified minor carvings, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period. At the top of the panel is a horseman, standing figure and unidentified subject.

The seven wild yaks, half circle (hunting trap?), unidentified animal and other carvings occupy the lower two-thirds of the rock panel. On the upper third of the panel, a carnivore is pursuing a wild caprid. The horseman and standing anthropomorph do not appear to be armed. The subject on the upper right side of the panel has not been properly identified. It appears that most or all carvings on this rock panel constitute an integral composition, one chronicling or extolling the ancient relationship between Upper Tibetans and their most important game animals. The differential coloring of the carvings in the photograph is due to uneven light exposure.

Fig. 79. Two or more mounted figures, at least eight wild yaks and several other animals, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The two most obvious mounted figures are stylized in a manner reminiscent of centaurs. The larger example is shooting an arrow and the smaller one may possibly be throwing a lasso. Wild yaks are all around them in a demonstration of plentitude. There may possibly be another horseman and a standing human figure on this boulder, all part of what might be an integrated composition.

Fig. 80. On the lower part of the panel are various carvings (partially cut in photograph), far western Tibet. Protohistoric period. On the middle part of the panel is a standing archer, a mounted archer and three wild yaks. On the upper part of the panel are a wild yak and two or three other animals.

Both archers are hunting wild yaks in a show of skill and prowess.

Fig. 81. Close-up of standing archer and prey in fig. 80.

The hunter is depicted running toward the wild yak with his bow and arrow. The hunter must have been lying in wait for his prey.

Fig. 82. Various wild yaks, mounted archers and other figures on a large rock panel, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

Taken in the glare of direct sunlight the carvings on this rock wall not very distinguishable. These petroglyphs were deeply carved in friable rock, further blurring their forms. Across the upper middle band of the panel are two human figures brandishing large rectangular shields, and a carnivore chasing a wild ungulate. Below these petroglyphs are the two largest carvings on the panel: a horseman in pursuit of a wild yak. Directly below this pair of figures the same theme is once again repeated.

Fig. 83. Close-up of a horseman chasing a wild yak illustrated in fig. 82.

The human rider and head and horns of the wild yak are somewhat obscured in this image. Lines carved perpendicular to the contour of the wild yak’s back may possibly be arrows that have already found their target.

Fig. 84. Two or three horsemen (one is on left side of a fracture in the rock panel), four standing human figures, three wild yaks, and two other animals, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The uppermost standing figure may have a bow. To his right there appears to be a horse with something on its back. The other three standing humans do not appear to have weapons. The second horseman in close proximity to the standing figures may possibly be shooting a bow. Although hunting seems to be one theme of this rock art, its significance could be multivalent in character.

Fig. 85. Two mounted archers, two wild yaks, a wild caprid, and three other animals, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The two archers are shown on either side of the large wild yak in the act of hunting. Lines radiating from the back of the lower wild yak may be arrow strikes. The two quadrupeds with hooked tails at the top of the rock panel appear to be carnivores attacking the upper wild yak. The figure to the left of the upper wild yak is not identifiable.

Fig. 86. Two mounted archers attacking three wild yaks and probably a wild ass and what looks like a hunting dog dominate the top of the boulder, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period. Lower on the panel are two more wild yaks and carvings of other animals.

The apparent hunting hound attacks wild yaks from the rear. The two mounted bowmen are aiming directly at their prey. The bristly mane of the figure farthest from the hunters in this group of animals identifies it as a wild ass. The two isolated wild yak petroglyphs on the lower portion of the boulder are typical solitary portraits of the animal (this genre of wild yak rock art will appear in another Flight of the Khyung). On the left side of the boulder is what appears to be a lone wild ass.

Fig. 87. Four mounted archers outflanking three wild yaks and a wild caprid, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This composition is suggestive of an encircling technique generally known as the ring hunt. If the rock art of Upper Tibet is an accurate indicator of ancient hunting techniques (and there is little reason to think that it is not), a limited number of personnel were involved in the actual slaying of wild yaks. There is no indication in this corpus of rock art that wild yaks were completely surrounded; rather a form of hunting dependent on the outflanking of prey seems to be depicted.

Fig. 88. On this rock panel there are at least twelve horsemen and perhaps four wild yaks, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This complex rock art scene is unusual because hunters outnumber game animals. It indicates that larger parties were indeed involved in wild yak hunting prior to the historic era. The horsemen are depicted without bows or with poorly rendered ones. The wild yaks are concentrated on the left edge of the panel. The best-defined example is situated in the upper left corner of the image.

Fig. 89. Close-up of three horsemen on lower right side of panel illustrated in fig. 88.

Like other examples in the composition, these three riders appear to be holding the reins of their mounts.

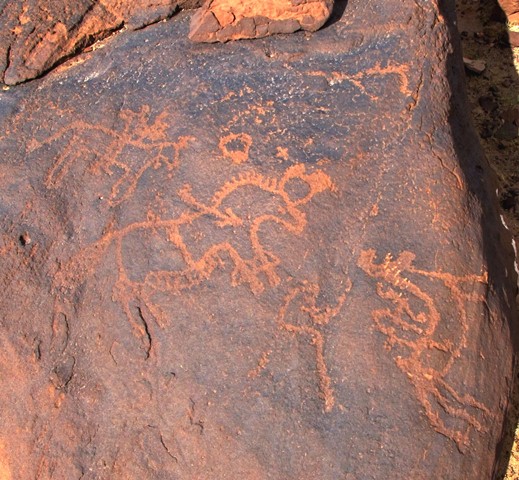

Fig. 90. The largest concentration of rock art on a single rock face documented in Upper Tibet, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

There are around 250 individual figures on this rock face, all of which were carved in the same time frame.* The most common figure is the wild yak, followed by wild caprids, standing figures (some with shields) and horsemen, in that order of precedence. On the upper left side of the rock face are two oblong forms pinched in the middle. These are copies of more ancient mascoids found in northwestern Tibet. To the left of the lower pseudo-mascoid is a line of birds. The single largest anthropomorphic figure wields a bow and is situated to the right of the lower pseudo-mascoid. It is not clear how many separate compositions have been cobbled together on the rock face. In any case, they are well matched and exhibit uniform thematic and technical qualities. Aside from the hunting of wild bovids and caprids, figures with shields and possibly swords evince a martial theme (dueling figures will be the subject of another article in Flight of the Khyung). A wild caprid in the Eurasian animal style is found on the upper right edge of the panel.

On this rock art, also see Bellezza 2002a, pp. 146, 147, 257 (fig. XI-1l), 258 (figs. XI-2l, 3l).

Fig. 91. Horseman and two wild yaks on upper right edge of rock face illustrated in fig. 91.

The horseman appears to have a bow but he is not directly confronting the two wild yaks situated behind him.

Fig. 92. A horseman on either side of a wild yak and two other figures on middle bottom of rock panel illustrated in fig. 90.

The archers may be armed with bows but the carvings are too rudimentary to make a positive determination. The carving in front of the horseman on the left may possibly be a hunting hound. The large lower figure is unidentified.

Fig. 93. Panel with at least nine wild yaks, four horsemen, three standing anthropomorphs, and possibly other types of animals, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

In the middle of the panel two horsemen (one seems to be brandishing bow) pursue a wild yak. On the upper right side of the panel, a standing figure chases or stalks a wild yak. Below these two scenes, on the right edge of the panel, there is an animal with a large head, gaping jaws and pointed ears. This appears to be a carnivore such as a tiger. Below the ostensible carnivore is a horseman and below it, on the edge of the panel, is a circle. To the left of the carnivore there appears to be another ambulatory human figure. On the bottom right side of the panel are two wild yaks and possibly a horseman. Above and to the left of the figure chasing or stalking a wild yak is another anthropomorph with partially extended arms, attired in what appears to be a knee-length robe. Further to the left are several wild yaks. This panel of figures was carved in the same time frame and possibly by the same hand. It appears to depict various activities such as wild yak hunting, possibly the taming of wild yaks, and perhaps ritual or mythic themes as well.

Fig. 94. Rock face densely packed with at least 12 wild yaks, one or more wild caprids and six horsemen, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This busy scene of wild yak hunters and other figures may represent an integral composition, a tableau of the way of life of the ancient hunter. On the lower right side of the panel is a wild yak carved in the Eurasian animal style. Founded upon curvilinear schema, both its front and rear haunches are ornamented with volutes. As in fig. 90, this petroglyph was integrated into a much larger assembly of indigenously styled figures.

Fig. 95. Close-up of bottom right side of rock panel illustrated in fig. 94.

The large horseman is discharging an arrow at a wild yak. Directly above him is a more indistinctly carved horseman.

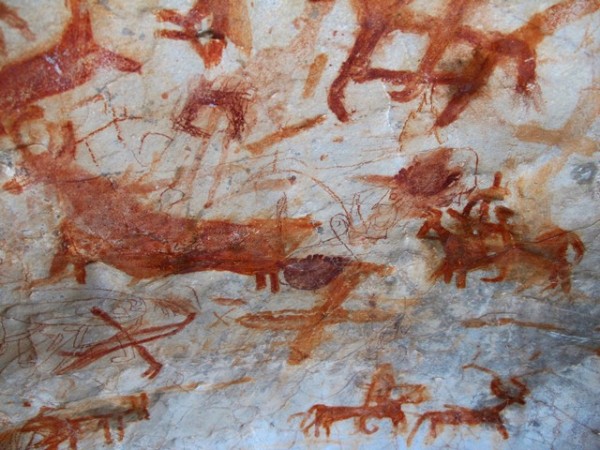

Fig. 96. Mounted archer slaying a wild yak in the middle portion of the photograph, eastern Changthang. Early Historic period. This composition is found among many other pictographs painted in a recess in a large limestone formation. They include another wild yak hunting scene on the bottom right side of the image.

The horseman is firing upon the wild yak, an arrow having already struck the animal while others are shown whizzing in the air toward their target. Below these two figures is an analogous one, consisting of a fleeing wild yak with an arrow protruding from its back. Many other red ochre pictographs painted at various times surround these two wild yak hunting vignettes; they include a cruciform and what appears to be a bow and arrow (bottom center and bottom left of image).*

The recess in which these pictographs were made is illustrated in Suolang Wangdui 1994, pp. 148, 149.

Wild yak hunting rock art dating to the Early Historic period is very uncommon in Upper Tibet. In that time, rock art production was very much reduced and the quality of execution heavily degraded. With the rise of the literacy and the written word, rock art as a prime conveyor of cultural knowledge lost its luster. While literary sources indicate that wild yak hunting remained an important social and economic activity in the Early Historic period, very little of it is recorded in the dwindling rock art output.

Interspecies hunting

In the rock art of Upper Tibet it is fairly uncommon for wild yaks to be depicted with other types of prey. Wild caprids occupy a different habitat, one hardly conducive to hunting on horseback, the mainstay of wild yak hunting. On the other hand, deer appear to have occupied the high plains and basins of the region, as did the wild yak. Their overlapping ranges furnish an environmental justification for portrayal in integrated hunting scenes. Moreover, the deer, like the wild yak, is an exceptionally important animal in the mythic, ritual and cultic universe of Tibet. Deer and deer hunting rock art will be the subject of another article in Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 97. Mounted archer chasing wild yak and stag, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

Most of the rock panel upon which these carvings were made has broken away obliterating whatever rock art was on it. All that is left is a single horseman armed with a bow attacking a wild yak and a stag, two of the most important game animals in Upper Tibet. The wild yak has horns forming a circle and the stag large antlers with vertically arrayed tines. One or two smaller figures are located below the stag.

Fig. 98. Horseman chasing wild yak and possibly a smaller wild ungulate as well, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

The horseman probably armed with a bow and arrow approaches the wild yak from behind. What appears to be the hunter’s hound is shown just above the tail of the wild yak. The well executed lower animal is either a deer or antelope. Its head has been obliterated. The body of this figure is adorned with a double volute motif. This carving was conceived upon a curvilinear schema typical of Eurasian animal art in Iron Age Upper Tibet.

Fig. 99. Four wild yaks, four stags, wild caprid and a mounted archer, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

This rock art presents a comprehensive view of hunting in ancient Upper Tibet. The horseman is coursing the stags and wild yaks. The stags form a single line, their legs deeply flexed as if running at top speed. This implies that they are within the sight of the hunters. The four yaks form two pairs arranged on opposite sides of the composition. A wild caprid (identifiable by its downward arching horns), an important game animal in its own right, has been added to the composition (middle of image).

Fig. 100. Close-up of upper portion of hunting scene illustrated in fig. 99.

This is a conventional wild hunting scene, whereby a mounted archer shoots an arrow at a fleeing wild yak.*

For this rock art, also see Bellezza 2002a, pp. 143, 246 (XI-6g).

Fig. 101. Two horsemen, wild yak, five antlered deer and three other animals are fully visible in this image, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period. The upper part of a sixth stag and the long-tailed carnivore pursuing it can be seen at the bottom of the photograph.

The upper horseman is armed with a bow and arrow and appears to be shooting at the wild yak in a conventional presentation of hunting in Upper Tibetan rock art. The wild yak may be shown with an arrow strike in the neck. It is not clear if the second horseman is armed. The animal directly above the wild yak has not been identified. The flexed legs of the animal above it and the folded legs of the animal at the very top of the rock panel seem to identify them as cervids. Three other antlered deer have folded legs and may depict the animals at rest. If so, this composition is more than a hunting scene, reflecting other ecological aspects of the animals shown. Alternative components of cultural expression may also be indicated, possibly encompassing the ritual, mythic or cultic.

Fig. 102. Central portion of a rock panel with two horsemen chasing two or three wild yaks and a stag, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The bow and arrow of the upper horseman is discernable. In addition to the figures illustrated here there are more than twenty-five others consisting of wild yak hunters as well as a tiger attacking a stag. Like fig. 101, the rock panel partly illustrated in fig. 102 portrays both types of predator-prey cycles: wild carnivores and wild ungulates, and human hunters and wild ungulates. These two modes of hunting parallel to one another, the former informing the latter.

The many scenes of wild carnivores (tigers, wolves and possibly snow leopards) chasing and attacking wild yaks, deer and other wild ungulates in the rock art of Upper Tibet appear to have served as a prototype for hunters, who emulated the natural predator-prey relationship. This is especially indicated in compositions in which both major modes of interspecies hunting are represented. We might see the depiction of wild carnivores hunting wild ungulates as furnishing a religious rationale for human hunters, legitimizing and even sanctifying their venatic activities. The carnivore attack rock art of Upper Tibet will be featured in another article in Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 103. Two mounted hunters pursuing wild yaks and possibly other animals, far western Tibet. Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

The finely engraved mounted archer on the middle right side of the rock panel and the wild yak at the bottom middle of the panel constitute an integral composition dating to the Iron Age. To this panel another horseman (top left) and two or three unidentified animals were added at a later date. The largest amendment to the rock panel is that of the antelope with long swirling horns and double volute body ornamentation. This rock carving is an example of the Upper Tibetan version of the Eurasian animal style.

Here, as with many other desirable expanses of rock in Upper Tibet, carvers and painters added their own creations over time, many of which complemented those that came before, in acts of cultural affirmation, social belonging and historical ratification. Thus, hunting compositions and other zoomorphic art of varying periods occupying the same rock face, cave wall or boulder are often temporal progressions of the same themes and subjects.

Fig. 104. Mounted archer (bottom) next to standing human figure, standing archer (top), wild yaks and various other figures comprising three or more compositions, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The archer on horseback at the bottom of the image is shooting in the direction of a standing figure. Although these two figures appear to be part of the same composition, the relationship between them is uncertain. There are combat scenes in the rock art of Upper Tibet, but homicide does not appear to be graphically represented. Thus, the standing figure may be a groom or an associate of the horseman. He is rendered in bi-triangular form, a common style of human depiction in northwestern Tibet in the Protohistoric period.

The standing archer at the top of the image is shooting away from the animals on the rock panel. This seems to suggest that this hunter is portrayed in a triumphant attitude, not in sanguinary pursuits per se. The two animals with bushy tails and upward curving horns to the left of the standing archer appear to be wild yaks. Below these animals is a roughly carved quadruped with a rectangular body. Below it, in the center of the panel, is a wild yak with a belly fringe. To the left of the rectangular animal and wild yak with a belly fringe are a number of obscure carvings. To the right of the wild yak is an unidentified animal that was also finely engraved on the rock. Below and to the left of the wild yak with a belly fringe is a trio of figures, including (from left to right) a raptor with a swastika form, a raptor with a broad triangular body and tail and arm-like wings, and quadruped with long rear legs and sinuous body.

Horsemen and other human figures and wild yaks in various non-killing scenes

In addition to hunting and hunting-related scenes with wild yaks, humans and this wild bovid occur in several other pictorial contexts. In these alternative scenes, the wild yak is found in association with anthropomorphs with shields and possibly swords, chariots, mascoids, and other kinds of horse riders. This diverse range of subjects demonstrates the wide applicability of the wild yak to the culture of ancient Tibet. This animal emerges not only as vital to the social and economic realities of the region, but as instrumental to its cognitive universe, as articulated in myth, ritual and religious belief.

Fig. 105. Two anthropomorphs with rectangular shields and two wild yaks are recognizable on this boulder, far western Tibet. Probably Protohistoric period.

Rectangular shields occur in a number of dueling or sporting scenes, supporting this assignment of object type to the rectangular motif. The two standing figures also appear to be carrying something in the other hand. Swords are seen in various dueling scenes, but they are usually depicted raised. Both anthropomorphs wear knee-length robes that spread out below the waist. The upper wild yak is complete while the lower specimen was left unfinished by the artists. The identity of the other carvings on the same boulder is unknown. The theme conveyed by this rare scene can only be speculated upon. Perhaps warriors are depicted, the wild yaks symbols of martial strength or affiliation. Ritual or mythic themes should also be considered as alternative interpretations.

Fig. 106. Anthropomorph with linear object in raised hand and circular object held out in the other encountering three animals (two of which appear to be a wild yaks), western Tibet. Protohistoric period.

The right arm of the human figure is raised and he is wielding a linear object that may be a sword. In the other hand he holds out a large round object. The raised middle of this object is rendered as a smaller circle. This may possibly be a shield; however, round shields are very uncommon, if they are found at all, in the rock art of Upper Tibet. In the historic era round shields were made and used in western Tibet, but more ancient examples have not surfaced to the best of my knowledge. In any case, the stance of the anthropomorph recalls that of a warrior in a classic battle pose.

As noted in Part 1 of this article, in more than 250 portrayals of wild yak hunting in Upper Tibet, the bow and arrow is the preferred weapon. An individual hunter on foot with weapons effective only at close quarters could hardly withstand a charge by wild yaks. Therefore, other interpretations for this scene must be sought. If it is ritualistic in nature, perhaps the animals are demonic representations about to be slaughtered by a warrior-priest. Many prehistoric sacerdotal figures bearing arms are recorded in Bon literature. If the composition is mythic in nature, the anthropomorph could possibly be a hero or divinity facing an enemy in zoomorphic form. An alternative interpretation of this scene is that a drummer is invoking animals in a ritual performance.

To the left of the human figure is a long-tailed animal rearing up in the opposite direction. Perhaps this is a carnivore helper or tutelary deity, aiding the warrior in combat or the priest in ritual. Two or three animals are portrayed coming towards the human figure. The one nearest him is clearly a wild yak, as its upward pointing, double curved horns and upright bushy tail illustrate. The animal farthest from the ostensible warrior, the largest of the three, may also be a wild yak. However, it seems to lack horns, a defining trait of wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet. The carving between these two zoomorphic depictions seems to be another animal but the graphic evidence is inconclusive. Carved lines on the right end of the rock panel do little to enhance our understanding of the scene depicted.

Fig. 107. On the top of the rock panel there are two wild caprids and what appears to be a wild ass, far western Tibet. Iron Age or possibly Protohistoric period. Along the middle tier of the boulder face is an incomplete circle, a circle divided into four quarters, and a horseman holding a bow or some other implement. In the middle of the bottom part of the panel is a wild yak and what appears to be a wild caprid to the right. On the bottom left side is a chariot.

All the figures shown in the photograph exhibit common production, stylistic and wear traits, indicating that they were made in the same time period as complementary representations. The carvings may even possibly have been the handiwork of a single individual. To the right of the petroglyphs illustrated are other matching subjects on the same boulder. They include another horseman (immediately to the right of the one shown above), several wild caprids and a wild yak (a portion of is submerged in the soil).

Of special interest is the chariot carved on the left side of the panel.* Much effort went into depicting its salient features, including two spoked wheels, car, axle, yoke and two draught animals. The round circle extending behind the square box appears to represent the head of charioteer. Each wheel has nine spokes and this numerical arrangement is not likely a coincidence (in Part 2 of this article, two suns carvings with nine rays are discussed). The nine spokes of the chariot wheel, like the nine rays of the sun in equally ancient rock art, probably had cosmological significance, as enneads of deities, weapons and mountains did in more recent times in Upper Tibet. The carvings of the two wheels on the same panel may have solar connotations, probably putting them in close correspondence with chariot wheels and sunbursts (wheels and discs will be the subject of an upcoming article in Flight of the Khyung).

On chariot rock art in Upper Tibet (and Ladakh) and its historical and cultural relationship to the rock art of north Inner Asia, see August 2010 and November 2011 Flight of the Khyung; Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 32–40, 71, 75, 76. The introduction of the chariot in China in the second and early first millennia BCE constitutes a cultural and technological transfer of long duration, one element in a wider range of contacts with Mongolia, Central Asia and even Eastern Europe (Shelach-Lavi 2015: 16). In all likelihood, similar observations can be made for the chariot carvings of Upper Tibet, which appear to have been made from the late Bronze Age to the late first millennium BCE. The geographic placement of Upper Tibet interposed between the Subcontinent and Xinjiang (East Turkestan) would have facilitated interactions with peoples of these territories, and perhaps with more distant places as well. I will return to the chariot rock art of Upper Tibet and its dating in a future issue of Flight of the Khyung.

Dates postulated for chariot rock art by Jacobson-Tepfer (2015) reflect current scholarly opinion, but they have not been verified using chronometric methods. It is thought that wheeled vehicles (chariot, wagon and cart) appeared abruptly in the rock art of north Inner Asia (Kazakstan, Tuva, Altai, Mongolia, and North China) in the middle of the second millennium BCE and endured until the end of Bronze Age (ibid., p. 193). At that time, the nomadic world became fully dependent on the horse and it appears that chariots disappeared from the rock art record (ibid.). Hundreds of chariot carvings dating to the second half of the second millennium BCE are found in north Inner Asia, and almost all are presented as seen from above or in a split perspective (ibid., p. 195). Without exception, this perspective also characterizes Upper Tibet rock art portrayals. It is not clear if the Afanasiev, Andonovo or Okunev cultural complexes were responsible for chariot rock art in the eastern steppes, as no actual vehicles have been discovered in their burials (ibid.). Chariots disappear from the rock art record of north Inner Asia in the early Iron Age, replaced by horse riding scenes (ibid., pp. 210, 211). Chariots in the rock art of Inner Asia have been interpreted variously by researchers as vehicles belonging to an emerging male warrior aristocracy, a platform for ritual activities including those related to death, and as a status symbol (ibid., pp. 194, 195). Most chariot petroglyphs in Mongolia are located on boulders situated on slopes or in terrain not accessible to light vehicles, not on obvious routes through the highlands (ibid., 202, 204). Similarly, the boulder upon which the chariot in fig. 107 was carved is located on a very rocky and steep slope. Jacobson-Tepfer (ibid., pp. 209, 210) hypothesizes that due to the inaccessible locations, the drivers depicted in unusual aspects and improbable hunting scenes, chariot rock art in Mongolia may show the transport of the dead to their final resting places, or might represent scenes of an idealized afterlife; either way they were community memorials to the dead. The same observations may possibly be applicable to the chariot carvings of Upper Tibet.

As we have seen, the wild yak and wild caprids that make up half of the carvings on the boulder in fig. 107 were the common prey of hunters in Upper Tibet. The two horsemen among them, however, are not shown explicitly in the act of hunting. As such, a more encompassing theme for this group of rock art is indicated. Narrative expressions of the ancient way of life, with the horsemen and wild ungulates as cardinal props or symbols, appear to be behind this group of subjects. The chariot adds yet another dimension to the scene. Whether it is a representation of an imaginary or actual vehicle, the chariot is restricted to about two dozen occurrences in the rock art of Upper Tibet. The chariot’s limited currency and the technological and military power implicit in this kind of depiction suggest that it possessed elite connotations for the carvers of the boulder, endowing the composition with a socioeconomic and/or political component. Nevertheless, the cosmological underpinnings of this assemblage of carvings may possibly be its most dominant thematic feature. Moreover, the assemblage is typical of the region’s rock art repertoire, indicating that the chariot was indigenized and integrated firmly into the cultural universe of Upper Tibet.

Fig. 108. Two human figures holding upright objects flanking a yak, far western Tibet. Protohistoric period or possibly Early Historic period.

If the linear objects in the hands of the two anthropomorphs represent swords this might be an animal sacrifice scene. Yet, alternative interpretations (pastoralism, etc.) for this unique composition must also be considered. Much depends on whether the yaks depicted are wild or domestic animals. The composition is found on a large rock panel with about twenty-five other carvings of a comparable style and time frame. They include horsemen and wild ungulates (including at least one other yak).

Fig. 109. Rock panel with five wild yaks and several other carvings, far western Tibet. Iron age.

The petroglyphs of this panel are organized in at least two independent compositions. Of particular interest is the anthropomorphic figure riding a wild yak at the top of the panel. This figure has outstretched arms in an acrobatic or provocative gesture. Yak riders form an intriguing subset of rock carvings in Upper Tibet (see July 2012 Flight of the Khyung). A study of this genre strongly suggests that the wild form of the animal is being represented. If this is indeed the case, the riders are probably heroic or numinous characters, not humans. It should be noted again that a number of territorial and personal deities ride wild yaks in the ritual texts and folklore of Upper Tibet. This religious custom may stem from older cultural traditions, as articulated in rock art. Yak riders constitute some of the most convincing evidence indicating that the prehistoric pantheon of Upper Tibet is represented in the rock art of the region.*

There are examples of loop-headed anthropomorphic figures standing on horses and that of bowmen standing on yaks in Ladakh. Such scenes occur mostly in the lower portion of the region, along the Indus River in the environs of Dah. See Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 29.

Fig. 110. Anthropomorphic figure standing on the back of a wild yak with two or three additional wild yaks, a couple of other wild ungulates and possibly a horseman on the opposite side of the rock panel, far western Tibet. Iron Age.

The compositional organization of the carvings on this rock panel is somewhat ambiguous. The wild yak with the rider and the similarly sized wild yak to the left appear to be part of the same composition, as does the wild caprid on the upper left side of the panel. The shallower bruising on the rock appears to constitute other compositions. Again, the identity of the rider is in question. Standing on the back of a wild yak is no mean feat, suggesting a mythic or supernatural identity for the rider. Perhaps the composition depicts a patron spirit or guardian of wild yaks. I shall refrain from further speculation.

Fig. 111. On the top of the boulder face a rider of an equid and a rider of what appears to be a wild yak are visible, far western Tibet. Late Bronze Age. Below the equid rider is another equid. The rest of the image is dominated by two mascoids (anthropomorphic visages in emblematic form).

The style of the figures and the presence of mascoids, a subject with wide dispersal in Inner Asian rock art, indicate that these carvings are probably best dated to the late Bronze Age.* In terms of style and wear, the rock art of this boulder forms an integral whole, even if various hands were responsible for its creation. The upper surface of the boulder is completely covered in carvings, mostly consisting of mascoids which are at least seven in number. There are also two or more other wild yak carvings on the rock. All of these carvings are heavily re-patinated and eroded. As with chariots, wild yaks were seen as a fit accompaniment to the mascoid art in Upper Tibet. This is illustrative of an indigenization process whereby Upper Tibetans exploited an interregional icon for their own cultural purposes.

For a comparative study of mascoids in Upper Tibet and Ladakh, see December 2011 Flight of the Khyung; Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 40–45. A more comprehensive study of Upper Tibetan mascoids will appear in a future issue of Flight of the Khyung. Recently, members of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society discovered two early mascoids in Spiti. These mascoids are closely related to those in Upper Tibet and will be featured soon in Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 112. A close-up of the rider illustrated in fig. 111. The orientation of this and nearby figures indicates that this was the top portion of the composition, although the boulder face is on the horizontal plane.

This is the only example of an equid rider directly connected to early mascoid art in Upper Tibet. Although there are later mascoid carvings in Upper Tibet, these ‘imitations’ are of another order of artistic representation. The anthropomorph’s arms are outstretched and it appears to be standing erect on the back of its mount in an impressive show of riding skill. The identity of the mount is unclear: it may be a wild ass or horse. A line extending from its face thematically links it to the equid below and other carved figures on the boulder. Perhaps Upper Tibetans were involved in the taming and riding of wild asses or horses in the late Bronze Age, which was mirrored in ritualistic elements of their art. However, if a late Bronze Age date for the petroglyphs on this boulder withstands further scrutiny, the rider may not be a human figure but rather a heroic or divine personage.

Fig. 113. Close-up of rider of what appears to be a wild yak illustrated in fig. 111.

The anthropomorphic figure has one arm raised and one extending downward on the back of the mount. A set of horns surmount the animal’s head (this trait and its massive body are indicative of a wild yak). The line extending from the face of the animal links it to other carvings of the same composition, betokening of an overarching narrative theme. As with the equid rider, a heroic or divine character can probably be ascribed to the rider.

Fig. 114. Standing anthropomorph making contact with animal resembling a yak with another anthropomorphic figure below, eastern Changthang. Protohistoric period.

There are two horn-like extensions are on the head of the standing human figure.* The arched line between it and the animal may be a bow (no bowline is shown), but it is pointed towards the hunter signifying that it is not in use. One arm of the anthropomorph appears to rest on the head of the animal. This quadruped with its massive body, belly fringe and what may be a bushy tail resembles a yak. Nonetheless, the possibility that it is a large dog or some other kind of animal cannot be ruled out. A kneeling figure touches the front hoof of the animal and its head makes contact with the standing anthropomorph. The red ochre line to the right of the legs of the kneeling figure is not part of the same composition. The identity of this scene is questionable. I have speculated that it may represent the taming of a wild yak, and the lower figure a subterranean spirit such as the lu (klu).† Perhaps, but other interpretations are also admissible. Certainly, the depiction of a mythic event or ritual performance should not be ruled out.

For this rock art, also see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 145 (fig. 182); Bellezza 1997.

In his groundbreaking work on Upper Tibetan rock art, Suolang Wangdi (1994), interprets a number of prehistoric compositions as depicting pastoralism; i.e. pasturing and stock rearing. My analysis of this rock art suggests that most of it is actually dedicated to other functions. For example, Suolang Wangdui (ibid., p. 79 [fig. 57]) interprets an anthropomorph with three yaks as a herdsman. However, other interpretations of this composition should be considered. A scene from a northwestern site called mTha’-kham-pa ri is interpreted as depicting domestic yaks and goats (ibid., p. 90 [fig. 72]), when it may show a human running in the direction of wild yak and what could be two hounds. A composition from Rgya-gling (central Changthang) is also perceived as seemingly pastoral in nature (ibid., 118 [fig. 126]). This Iron Age rock art depicts two wild yaks confronting one another, as in combat, and possibly a smaller third figure below them as part of the same composition. However, it does not appear to have anything to do with yak herding. Another Iron Age scene from Rgya-gling is interpreted as showing two men leading two yaks (ibid., p. 120 [fig. 130]). Indeed, one anthropomorph appears to be in contact with a yak; If so, this may be a scene of taming. In a composition from a western Changthang site Suolang Wangdui calls Tshwa-kha there are three horsemen and several yaks interpreted as herdsmen and livestock (ibid., 104 [fig. 97]). While this may be a pastoral scene, it probably dates to the Early Historic period, because it exhibits little erosion and was carved and abraded in a particular way with sharp metal tools. The same chronological and artistic observations can be made for a scene depicting yaks, a standing human figure, and a mounted archer facing in the opposite direction (ibid., p. 100 [fig. 91]). There is also a second standing anthropomorph on the right side of the composition. This may be a herding vignette but it could also be something else.

Next Month: More marvels from Tibet await you!