August 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to the Flight of the Khyung marking nine years of this newsletter’s publication! This 109th issue is focused on cultural interconnections between Spiti and Upper Tibet and Ladakh in antiquity. There is much beautiful and mysterious rock art to see as we plumb the depths of cultures in Greater Western Tibet.

As part of a special series on Spiti, this month’s offering complements articles in the last three issues of Flight of the Khyung, Readers are encouraged to refer to those first. For an introduction to Spiti, see the May newsletter. For a review of its early cultural history see both the May and June issues. For an introduction to the rock art of Spiti consult the July newsletter.

Visitations from Upper Tibet and Ladakh: A survey of trans-regional rock art in Spiti

Introduction

This article presents rock art in Spiti (Spi-ti / Spyi-ti) with affinities to rock art in Upper Tibet and Ladakh. This body of parallel rock art demonstrates that from the Iron Age (begins circa 600 BCE) until the Early Historic period (ends circa 1000 CE) the culture of Spiti did not exist in isolation. Rather, the rock art record indicates that exchanges with adjacent parts of the Tibetan plateau were taking place over this long span of time. The effect of these transmissions was to add new stylistic and thematic elements to the rock art of Spiti. Implicit in the acquisition of new forms of artistic expression is the absorption of certain cultural inputs emanating from Upper Tibet and Ladakh.

Spiti adjoins both Upper Tibet (sTod) and Ladakh (La-dwags) and these are the regions that significantly enriched its rock art repertoire. A survey of Spiti rock art suggests that the greater of the two cultural contributors was Upper Tibet, that vast region lying immediately to the east. This is not surprising given that traditionally the only reliable year-round route out of Spiti joins it to Guge in Upper Tibet.

Spiti is a small region, especially compared to Ladakh and the vastness of Upper Tibet. As noted in last month’s Flight of the Khyung, Spiti has a minimal number of pre-Buddhist monuments, in contrast to the well developed early monumental infrastructure of Ladakh and Upper Tibet. Spiti also has a historical record of being under the political domination of its two larger neighbors from the late 10th century CE to the early 19th century. Thus, it probably can be assumed that many cultural flows enriching the rock art of Spiti came from its more powerful neighbors to the north and east, Ladakh and Upper Tibet.

Cultural transfers to Spiti are likely to have varied considerably over time and the changing historical circumstances of the greater region. Many agents of cultural influence must be considered, all of which remain hypothetical at this time for a lack of solid archaeological evidence. The potential bearers of cultural information and inspiration that materially affected rock art in Spiti can be outlined as follows:

Military (raids, invasion, conquest)

Political (arrival of emissaries, confederation, vassalage)

Religious (cultic participation, missionary activity)

Economic (trade, tribute, gift giving)

Technological (introduction of agriculture, metal implements and weapons and ceramics)

Social (adoption of new values, mores and fashions)

Chronological terminology used in this article (for an explanation, see last month’s Flight of the Khyung):

I. Prehistoric epoch

- Early Iron Age (circa 900–500 BCE)

- Iron Age (circa 500–100 BCE)

- Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 630 CE)

II. Historic Epoch

- Early Historic period (630–1000 CE)

- Vestigial period (1000–1300 CE)

- Later Historic period (post-1300 CE)

This survey of rock art is divided as follows:

- Tigers

- Horned eagles

- Equids

- Wild yaks

- Cervids

- Ceremonial structures

- Symbolic compositions

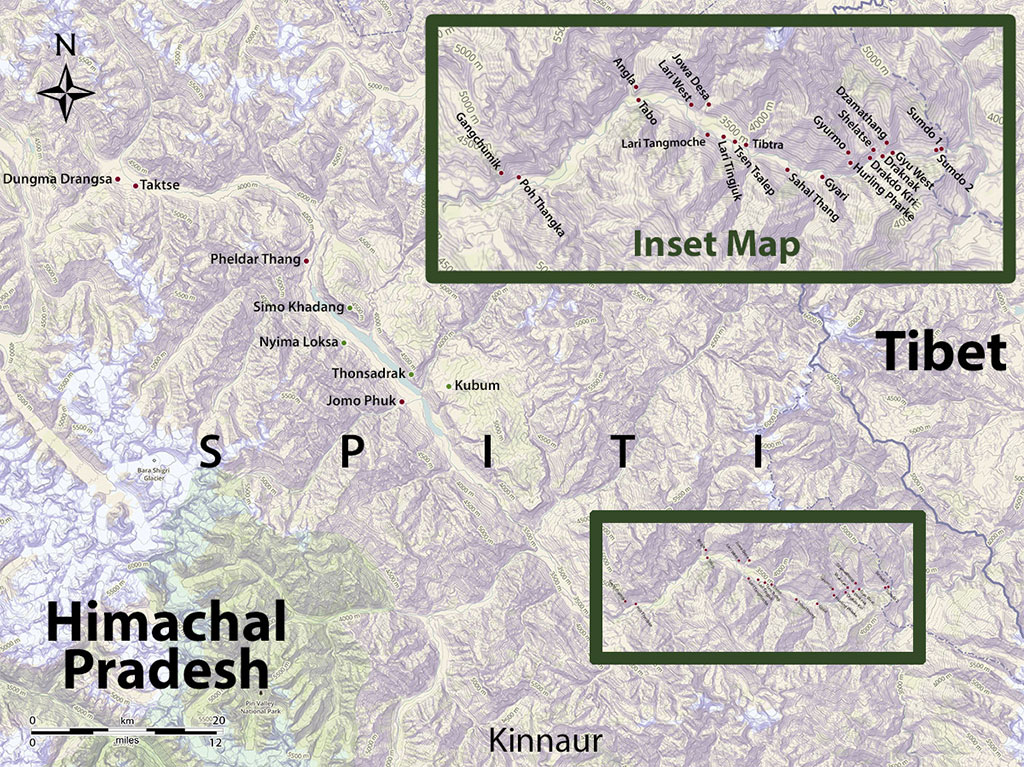

The rock art sites of Spiti: red dot denotes petroglyphs, green dot denotes pictographs. Map by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza. Click to enlarge.

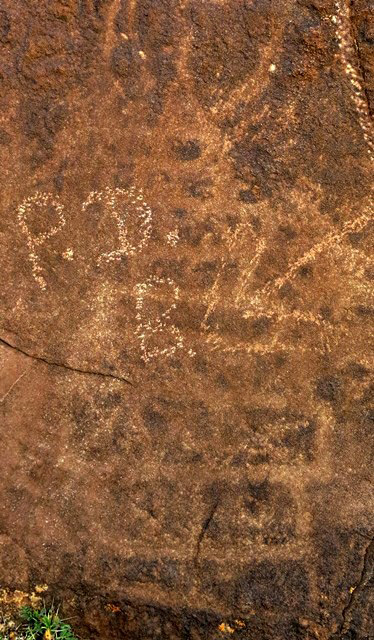

1. Tigers

We begin this survey of extraneous cultural influences in the rock art record of Spiti with the tiger, an iconic figure in carvings of Greater Western Tibet (Spiti, Ladakh, Tö and Changthang) and regions of north Inner Asia (Greater Mongolia, Ningxia, etc.). Tiger rock art throughout Inner Asia is identified typically by the depiction of stripes, long sinuous tails, gaping mouths, and claws and fangs in some cases.

The largest concentration of tiger rock art in Spiti (eight different examples) is located at its southeastern frontier, near the settlement of Sumdo (Sum-mdo; el. 3085 m). The petroglyphs of Sumdo 2 are perched on a gigantic boulder that rises out of the left bank of the Spiti river. Most of the carvings have a southern aspect. This big mass of rock is located just below the main road in the Spiti valley. Unfortunately, in recent years its expansive surface has been disfigured by vandalism and graffiti.

Sumdo 2 is one of the earliest rock art sites in Spiti, boasting carvings that can be attributed to the Iron Age (500–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 630 CE). Perhaps the oldest tiger petroglyphs at Sumdo 2 were made in the Early Iron Age (900–500 BCE), but it is not yet possible to support such an early periodization.

Many rock art subjects in Sumdo, in terms of their subject matter, style and techniques of production, exhibit Upper Tibetan cultural influences. Sumdo 2 is situated very close to the old trail running between Spiti and the Chusum (Chu-gsum) region of Guge (Gu-ge) in western Tibet. Traditionally, this was the only route leading to and from Spiti open regularly in winter months. Other routes exiting Spiti (to lower Kinnaur, Lahul and Ladakh) traversed passes usually closed in the wintertime on account of heavy snow. A route to Chango and Nako in upper Kinnaur was sometimes open in the winter but these villages (particularly Nako) are vulnerable to heavy snowfall, which periodically led to its closure.

The carving techniques used to produce the tiger carvings of the Iron Age at Sumdo 2 contrast with typical ones employed in the creation of most petroglyphs in Spiti. These tigers exhibit more finely etched lines and were executed with much care and precision. Rather than a coarse bruising or abrading of the stone surface, it was painstakingly removed using more evolved engraving techniques and probably different tools. It appears therefore that the creation of the tigers entailed investment of more time than the bulk of Spitian petroglyphs.

The tiger carvings of the Iron Age differ in style from what we might call indigenous or ordinary Spitian rock art. These tigers were carefully modeled with attention to distinguishing anatomical features of the animal such as stripes, claws and long tails. An awareness of the gait and the manner in which tigers pounce when attacking is also embodied in the forms of the engraved tigers. Thus, this art has a vivid and graceful quality. Also, these tiger carvings are between 30 cm and 40 cm in length, larger than many animal petroglyphs in the indigenous rock art of Spiti.

One of the most distinctive and dominant styles of tiger rock art in Inner Asia is associated directly or indirectly with the complex of Iron Age cultures known as the Saka-Scythians. These carvings belong to what is called the ‘Eurasian animal style’, reflecting their trans-regional and trans-cultural distribution. It is within this wide purview that some tiger carvings of Sumdo 2 must be placed. The Eurasian animal style however is not widely represented in the rock art of Spiti, as illustrated by the absence of wild ungulates and carnivores with volutes and scrolls ornamenting their bodies. Animals with these kinds of adornments proliferated in the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh.*

For an analysis of Eurasian animal style rock art in Upper Tibet and Ladakh, see Francfort, Klodzinski, Mascle 1992; Bellezza 2002a, pp. 137–139; Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 45–49; Bruneau 2013; Bruneau and Vernier 2010; Lü 2010; October and November 2014 Flight of the Khyung. I noted animal style rock art at Sumdo during a visit to the site in 1994: “The petroglyphs found in Spi ti push the limits of Saka cultural penetration in the Himalaya to at least the 32nd parallel” (Bellezza 1997: 424). I should add that this does not necessarily mean Saka tribesmen visited Spiti but that styles of zoomorphic art with which they are associated spread that far south.The specific styles of Iron Age tiger rock art in Spiti indicate that they were transferred or modulated through Upper Tibet and possibly Ladakh. These regions are of course interposed between Spiti and other Inner Asian territories with animal style tiger rock art such as Qinghai, Ningxia and Mongolia.* The peculiar style and production techniques used to render tigers at Sumdo 2 strongly suggest that their creators actually came from Upper Tibet and/or Ladakh. Nevertheless, given the close proximity of Sumdo to Upper Tibet, the early tiger carvings of Spiti are more likely to be of Upper Tibetan origin.

A discussion of tiger rock art in Upper Tibet and Ladakh and its stylistic, compositional and chronological affinities to that of north Inner Asia is discussed in Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 51–53, 65, 66. For the links between Upper Tibetan and north Inner Asian animal style tiger rock art, also see November 2014 Flight of the Khyung. For a survey of western Tibetan tiger petroglyphs, their cultural historical context and indications that the carvings possibly reflect the existence of this carnivore in the region in ancient times, see August 2012 Flight of the Khyung. For black and white drawings of felines on rocks and deer stones in north Inner Asia, see Francfort 2002, p. 69 (figs. 19 (after Novgorodova 1984), 20). For tigers in the rock art of Ningxia, see Chen Zhao Fu 2006. For photographs of tiger rock art in Inner Mongolia, see the Bradshaw Foundation website article “The Tiger in Chinese Rock Art” http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/china_tiger/index.php .There are no definitive answers to why tigers in the Eurasian animal style were carved at Sumdo 2. Generally speaking, factors such as those outlined in the introduction to this article are implicated in their creation. Each of the tigers at Sumdo appears to have been made by a different hand. This imparts the impression that they may have possibly functioned as a kind of personal signature or mark of possession.

Sumdo is a strategic location. Like today, those occupying Sumdo in ancient times would have controlled an important geographic nexus, conferring access to western Tibet, Spiti and upper Kinnaur. The tiger is a widespread symbol of power and prowess (politically and militarily) in eastern Central Asia and East Asia. This is clearly true of ancient Tibet were the tiger was a symbol of the warrior and his bravery, weapons and dress. Therefore, tiger art at Sumdo might be seen as a symbol of military conquest and occupation. Such a hypothesis is strengthened by examples of more overtly aggressive rock art in Spiti that also exhibits Upper Tibetan influence. Tigers play a significant role in ancient Tibetan religious traditions as well, thus mythic and cultic traditions could have been a factor in fashioning feline rock art in Sumdo 2. For example, in Tibetan textual and ethnographic sources warrior spirits known as drabla (dgra-bla) take the form of tigers.

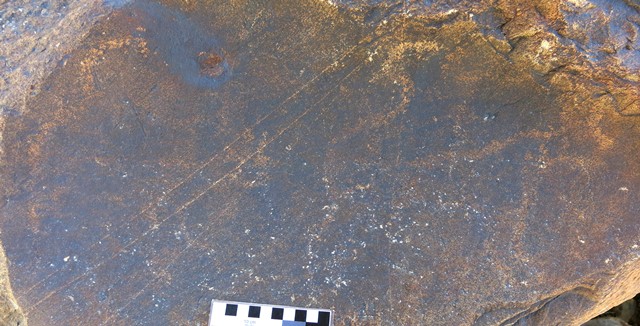

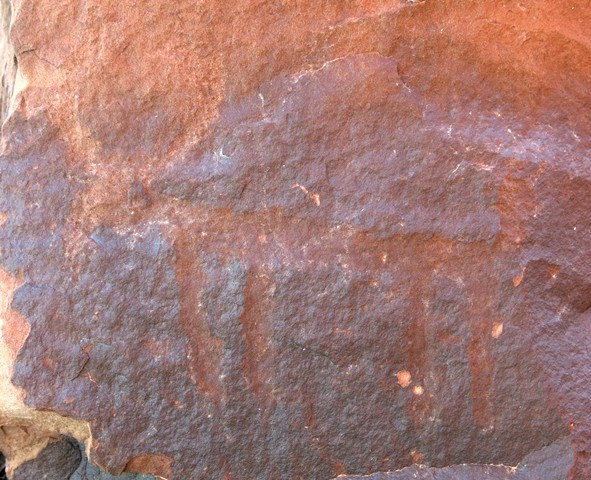

Fig. 1. A tiger petroglyph (32 cm long) finely etched on the giant boulder of Sumdo 2. The positions of the four legs appear to simulate movement. Iron Age.

This well-crafted petroglyph of a tiger strongly resembles one found in Guge, located approximately 150 km to the southeast (see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013: 141 [fig. V.20, upper tiger]; August 2012 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 9). Both specimens have similarly shaped heads (although the jaws of the Upper Tibetan example are open), prominent upright ears, clawed feet, tails that curl at the end (each in different directions) and V-shaped or almost V-shaped stripes that point to the right.

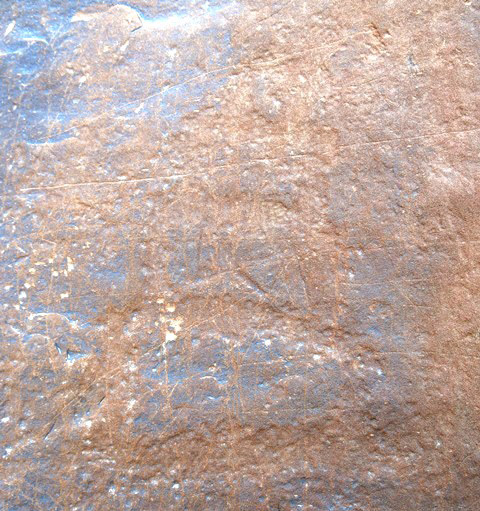

Fig. 2. Another adeptly engraved tiger petroglyph (33 cm long), Sumdo 2. Iron Age.

The tiger has an S-shaped tail, open jaws, upright ear, eye and V-shaped stripes that point to the right. The form and method of producing this long, lithe feline point to Upper Tibet, although there is no exact parallel known in its rock art. A tiger petroglyph at Zamthang (Zam-thang) in Ladakh and a copper alloy tiger talisman from Tibet also has V-shaped stripes but they point to the left (Bruneau and Bellezza 2013: 142 [fig. V.22], 143 [fig. V.23]).

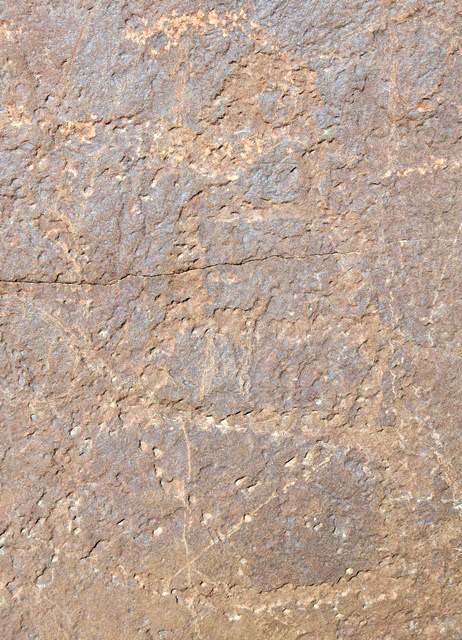

Fig. 3. The tiger in fig. 2 is part of an integrated composition consisting of a triad of wild animals, Sumdo 2. In addition to the feline, there is an ungulate and bird. It is not clear what species of herbivore is intended by the depiction of short, straight horns. The bird, also shown in profile with its wings folded, appears to be portrayed with a pair of horns.

The integrated nature of this composition is demonstrated by the aspect of the three animals, the same engraving technique used to produce them, and the uniform level of wear and re-patination. If the bird does indeed sport horns, it is a portrayal of the khyung, the legendary horned eagle of Greater Western Tibet (found in the rock art of Upper Tibet, Ladakh and Spiti).* A portrait of three different animals facing each other is encountered in Upper Tibet, as in the pictographs of Chedo (lCe-do). Birds, tigers and wild ungulates (such as wild yaks and antelopes) in combination are also depicted on early copper alloy objects from western Tibet (subject of a future Flight of the Khyung). These kinds of compositions must have had symbolic, ritual and/or mythic significance. Tibetan literature offers points of reference, but how these might be applied to a particular piece of rock art or object is not a clear-cut proposition.

For a khyung depicted in profile with its wings folded in the rock art of Upper Tibet, see January 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 2.

Fig. 4. A tiger springing up. It has a tail curled over the body, V-shaped stripes pointing to the left and four feet with claws, Sumdo (36 cm long). Iron Age.

The shape of the stripes, tail and the clawed feet of this tiger have considerable resemblance to tigers in figs. 1 and 2, but this petroglyph also recalls tigers in Upper Tibet and Ladakh that are more closely allied stylistically to animal style examples from north Inner Asia. These include a tiger in Rimodong (Ris-mo gdong, Ruthok) and one in Tangtse (sTang-rtse, Ladakh) chasing wild ungulates.* The Spitian tiger also resembles three specimens carved on a boulder in Alchi (A-lci), Ladakh (Francfort 1994: 40 [fig. 6]; Linrothe: figs. 83121, 83123, 83124). As Francfort (ibid., 39, 40) notes, these three felines are in a style aligned to the steppes. He dates this rock art to the 5th to 3rd century BCE.

Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 129 (figs. IV.20, 21). Also see Bruneau and Vernier 2010, p. 32 (fig. 7).

Fig. 5. What appears to be another tiger in the rock art of Sumdo 2 (34 cm long). The tail curling over the body, stripes and arched back of the animal are discernable. This petroglyph was deeply engraved into the stone surface but it is highly eroded, impairing recognition of its various distinguishing features. Iron Age.

Fig. 6. The stripes and what appears to be a sinuous tail suggest that this petroglyph depicts a tiger (40 cm long), Sumdo 2. However, it is so worn that very few details of the animal remain intact. Iron Age. The head of this tiger (facing left seems to have almost a teardrop shape, somewhat corresponding with the form of the tiger’s head in fig. 1.

The two stripes on the front haunches of the animal bend in opposite directions, recalling animal style art tigers of Rimodong, as in the one referred to above in the description of fig. 4. Indeed, from what can be seen, this tiger belongs to the animal style, bringing it in correspondence with feline art across Inner Asia.

Fig. 7. This animal with its elongated form, stripes, four legs conveying movement and long curling tail appears to be a tiger (38 cm long). Iron Age. This petroglyph is highly eroded and few anatomical details of the depiction have survived.

With its long, slim body and straight stripes, this specimen has certain similarities to a tiger petroglyph in Ruthok (August 2012 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 1) and a tiger petroglyph in Zamthang, Ladakh (Bruneau 2011, fig. 218). While the three tigers referred to here have less in common with the Eurasian animal style than others examined above, their affinities to one another draw them into a common grouping, we have called the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ (Bruneau and Bellezza 2013).

Fig. 9. Feline in the rock art of Ruthok. Protohistoric period.

Fig, 10. Pair of felines, Sumda Rikpa Bao, Ladakh. Protohistoric period. Image courtesy of Martin Vernier.

The two felines in fig. 8 appear to represent either tigers or snow leopards. They were carved on top of a boulder at the Dzamathang site. Similar style felines are found in the rock art of Ruthok (Ru-thog). Although the Ruthok feline pictured above was much more deeply carved, it shares a long winding tail, prominent upright ears, legs conveying the same kind of movement, and a similar body shape to the two specimens from Dzamathang. There are also similarities between the felines of Dzamathang and a pair found at Sumda Rikpa Bao in Ladakh (Vernier 2007: 6/12 [I11._23]; Bruneau 2010, fig. 209). The Ladakh felines face in opposite directions. There is also a comparable feline at the Ladakh site of Murgi Tokpo (Bruneau 2010: fig. 273). The parallels in form between these felines in Spiti, Upper Tibet and Ladakh indicate that they belong to an interrelated group of art designated the Western Tibetan Plateau Style.

Fig. 11. A tiger carving among many figures on a boulder, Tabo (el. 3285 m). Early Historic period.

This more crudely carved tiger has a stiffer appearance than the tiger art already discussed. Its various technical and stylistic traits are telltale signs that it belongs to a later period of figuration. This is corroborated by Tibetan inscriptions found in proximity to this style of rock art at Tabo, exhibiting uniform wear and re-patination qualities.*

Thakur (2008: 31) attempts to link the carvings of felines at Tabo (Ta-po) to those of Northern Pakistan, Ladakh and western Tibet. The felines depicted in Thakur’s article (ibid.) and others surveyed at Tabo, however, appear to belong to the Early Historic period and primarily represent indigenous styles and techniques of carving. Parallels in form and subject matter do show that this phase of rock art was a carryover of older rock art traditions in Spiti. Nonetheless, it is through the older traditions of figuration that tiger rock art in Spiti can be directly associated with trans-regional and trans-cultural tiger art of the Iron Age.

Fig. 12. A tiger in an indigenous style, Sumdo 2. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 13. A tiger in an indigenous style located to the right of the one pictured in fig. 12. Protohistoric period.

These two tigers appear to be in pursuit of a pair of ibexes situated on the same rock face to the left, which was carved in a similar fashion. These tigers were probably created in imitation of the earlier tiger rock art at the site. They are rendered in an indigenous style, characterized by a more rudimentary carving technique and a more naive form.

2. Horned eagles

One of the most unique and iconic figures in the rock art of Spiti heralding cultural bonds with Upper Tibet and Ladakh is the horned or crested eagle (khyung). The khyung, the king of the birds, as a distinctive and integral figure in the Tibetan cultural world, functions as a specific marker of cultural affiliation. This is demonstrated by the great number of place names throughout Tibet that include khyung in them (and in ancient times by the proliferation of personal names with khyung as a component).

The khyung, a pre-Buddhist religious and mythological paragon, appears to have become assimilated to the Indian garuda with the coming of Buddhism to Tibet. As is often pointed out, the garuda does not generally possess horns. The demise of the khyung as a kind of pre-Buddhist solar symbol is recounted in the Ling Gesar (Gling ge-sar) epic of Ladakh (Francke 1905a: 122–129), seemingly alluding to the rise of Buddhism in the region.

As a protective spirit, genealogical symbol, tantric god and metaphor for mind training traditions known as the Great Perfection (rDzogs-chen), the khyung, fulfills dozens of roles in Tibetan cultural and religious life. In an attempt to place khyung rock art in a cultural historical context, I will review just a small handful of this welter of traditions and practices. According to Tibetan tradition, the khyung was an important tribal progenitor in Greater Western Tibet, representing a major component of the Zhang Zhung kingdom (Karmay 1972: 11–13; Bellezza 2008: 288, 289; 2013: 173–175). Subsequently, the khyung became a totem or symbol for the Khyungpo (Khyung-po) clan, which is still well distributed in various ramified forms in Greater Western Tibet. A nuptial song from western Tibet mentions a world tree with six branches, six points and six birds, one set of which is associated with the khyung (Tucci 1949: 711–713). These were symbols of six major clans or lineages of the region. The Khyung clan is still active in Upper Tibet, Ladakh and Spiti.

In Upper Tibet and Ladakh, territorial deities (yul-lha) and warrior spirits (dgra-lha) often take the form of a khyung, ride on a khyung or have the khyung in their entourage. For example, a Yungdrung Bon text with a theogony of the great mountain god Nyenchen Thanglha (gNyan-chen thang-lha) states that he first manifested as a conch white khyung (Bellezza 2005: 179). According to Yungdrung Bon tradition, the khyung was also an important symbol of sovereignty for the kings of Zhang Zhung. Certain of these kings, as well as their high priests, are supposed to have worn headgear with the horns and other parts of the khyung as emblems of power and prestige (Bellezza 2008: 229, 239–242; 2010: 81, 82). Finally, in this résumé of the ancient religious and cultural functions of the khyung, mention of its role in archaic funerary rituals must be made. In Old Tibetan and Yungdrung Bon literature, the khyung and its horns have protective and psychopomp functions (Bellezza 2008, Part III: passim; 2013: passim).

It cannot be determined with any assurance which elements of the khyung persona in Tibetan literature and the oral tradition can be applied to horned eagle rock art in Greater Western Tibet. In general terms, we might assume that lore such as that reviewed above had a bearing on the creation of this art.

While we cannot know the purpose of khyung rock art (pictographs and petroglyphs) in Greater Western Tibet with any certainty, its antiquity is indisputable. In Upper Tibet, Ladakh and Spiti much khyung rock art is attributable to the Iron Age and Protohistoric period. The 17 or 18 specimens of khyung rock art discovered in Upper Tibet occur at 12 different sites, spanning much of Tö (sTod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang). The ten or so examples of the khyung in greater Ladakh are concentrated in the gorge country of Zanskar (Zangs-dkar), at the sites of Yaru (Yar-ru) and Yaru Zampa (Ya-ru zam-pa). This zoomorphic subject in the wider region helps define the Western Tibetan Plateau Style of rock art.*

On the khyung rock art of Upper Tibet, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 172 (fig. 303), 175 (fig. 310); 2002a, pp. 216 (fig. XI-17c), 217 (XI-17c, 18c), 221 (XI-26c), 234 (XI-4e, 5e); Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 144 (fig. V.26); January 2015, November 2014 (fig. 69), January 2013 and January 2012 Flight of the Khyung. On the khyung rock art of Ladakh, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, pp. 66, 67, 145 (figs. V.27, V.28); Bruneau 2010 (fig. 208); Thsangspa n.d., sites 8-9; 2014, p. 22 (figs. a-c).There are also copper alloy talismans known as thokcha (thog-lcags) in the form of the horned eagle. The oldest of these may date back to the Protohistoric period but the bulk of them date to the Early Historic period and to more recent times.*

On these khyung talismans see Norbu 2009, pp. 172–176; Bellezza 1998, p. 54 (pl. 27, 28), 59 (pl. 51–54); John 2006, pp. 139, 147–149.

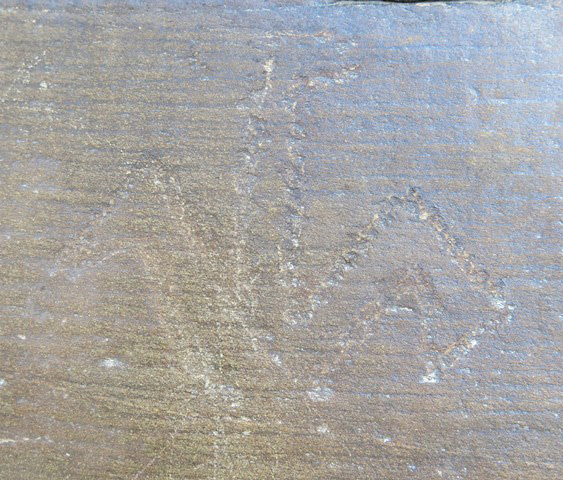

Fig. 14. A majestic khyung rock carving with fully spread wings, longs horns, pointed beak and triangular tail (24 cm high, 27 cm wing span), Sumdo 2. Note the double-curving left horn, a style of depiction also found in the wild yak rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh. Iron Age.

The style of this heavily re-patinated horned eagle and the engraving technique effecting the removal of a deep layer of the rock surface recalls khyung petroglyphs in Upper Tibet. While khyung rock art in Upper Tibet customarily have outstretched wings that point upward, all those of Ladakh have folded or downward pointing wings (cf. Bruneau and Bellezza 2013: 67). That the khyung of Sumdo 2 so strongly resembles counterparts in Upper Tibet points in that direction, as regards its origin or avenue of transmission. This rock art reinforces the picture gained from early tiger rock art at the same site indicating Upper Tibetan cultural affinities.

Fig. 15. The khyung carving at Lari Tinjuk (La-ri ting-mjug; el. 3260 m), with a triangular body sub-rectangular wings and prominent horns (15 cm high, 16 cm wingspan). Note the manner in which the wing and tail feathers were simulated by painstakingly removing tiny wedge-shaped bits from the surface of the stone. As in fig, 14, the horns have two curves. This petroglyph is very highly worn and re-patinated. Iron Age.

The intricacy and technical proficiency exhibited by this figure is not in keeping with the great majority of Spitian rock art, characterized by standard or indigenous styles and techniques. These differences are typified by the far less re-patinated wild ungulate partially visible above the right side of the horned eagle. Also above the khyung are two chronologically related petroglyphs (not pictured) that appear to portray an elongated striped yak and stag. These two species are characteristic zoomorphic depictions in Upper Tibet. There is also an anthropomorph on the same boulder typical of the Spitian style (it may date to a somewhat later phase of rock art). Although the quadrilateral wings of the khyung are outstretched, they are not pointing upward. There is also a body of raptor rock art in Upper Tibet with triangular bodies.*

For an example, see Bellezza 2008, p. 172 (fig. 304); 2002a, p. 29 (XI-16d); 2002b, p. 391 (fig. 49).

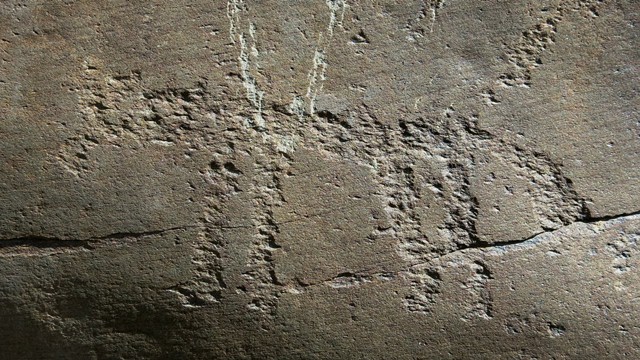

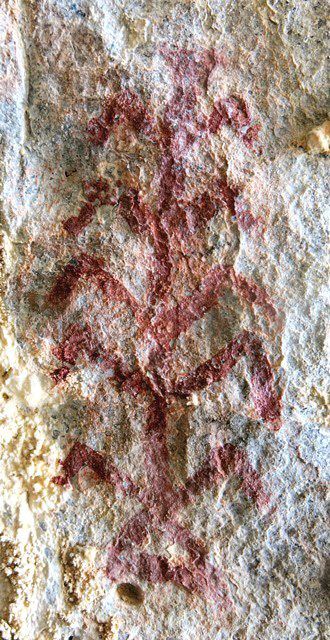

Fig. 16. A figure combining avian and anthropomorphic features (15 cm high), Sumdo 2. This finely engraved figure has a prominent triangular crest, a blunt beak or face, bi-triangular body and arm-like wings with fingers. Protohistoric period.

This is one of the only ornitho-anthropomorphic figures registered in the rock art of Spiti. Such figures (pictographs and petroglyphs) in various styles are fairly well represented in the rock art of Upper Tibet.* However, no figure resembling fig. 16 has been documented elsewhere. This unique composition has religious and mythological overtones; it may represent a kind of deity or shaman (among the deities and spirit-mediums of Upper Tibet there is much ornithic imagery and attributes).

For ornitho-anthropomorphic rock art in Upper Tibet, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 111 (fig. II.7); Bellezza 2000, pp. 45 (fig. 14), 50 (figs. 26, 27).Yungdrung Bon literature documents many examples of prehistoric priests and sages of yore manifesting as khyung and other raptors and flying around in space as a demonstration of their religious power. Also, priests and sages of yore are recorded as wearing costumes with avian qualities, which is also represented in the rock art of Upper Tibet.* How themes reviewed here might relate to the piece of rock art from Spiti is a moot point. The high standard of engraving, thematic counterparts in the rock art of Tö and Changthang, other rock art at the Sumdo 2 site with the same geographic affinities, as well the cultural lore surrounding birdman figures in Tibetan literature, indicate an interrelationship between the Spiti specimen and analogous figures in Upper Tibet.

A concentration of such figures is found at Thakhampa Ri (mTha’-kham-pa ri) in Ruthok. See Suolang Wangdui 1994, pp. 83 (fig. 62), 92 (fig. 76); December 2013 Flight of the Khyung.

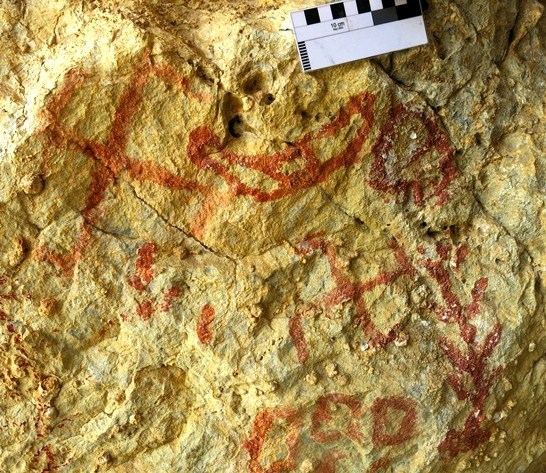

Fig. 17. What appears to be a khyung (14 cm high) in the pictographic art of Sinmo Khadang (Srin-mo kha-gdang, Gaping Mouth of the Ogress; el. 4720–4740 m). This raptor has wings folded in a diamond pattern and a triangular body and tail. This figure seems to have two large upright horns but the head was not very distinctly depicted. Protohistoric period.

Sinmo Khadang is a large cave suspended high above the village of Chichim (dKyil-khyim), just below the ridgeline that divides the main Spiti valley from the tributary valley of Kibbar (dKyil-bar). Sinmo Khadang is approximately 80 m long and has two mouths, which open up in both valleys: east (14 m wide) and south (8 m wide). From the south mouth a narrow ledge separates the cave from a 700 m vertical drop to the floor of the Spiti valley. Thus this cave occupies a powerful geomantic position. It contains around 100 red ochre pictographs of a closely matching and decidedly religious persuasion. They include numerous swastikas aligned in both directions, a variety of anthropomorphs in several dramatic poses, and the sun, crescent moon, tree and other symbols. In addition to the raptor, there are two separate paintings of ibexes in the cave.

Fig. 18. Another possible khyung, Tabo. Like the bird of Sinmo Khadang above, the body and tail are composed of inverted triangles and the wings fold inward in a similar manner. The head of the Tabo specimen is not very clearly rendered, also paralleling the design of the Sinmo Khadang specimen. Protohistoric period.

This bird is located on a boulder with many carved figures mostly dating to the Early Historic period, including the tiger in fig. 11. The existence of this bird in Tabo indicates that whatever religious or mythological traditions were connected to this type of figure permeated both lower and upper Spiti in the Protohistoric period.

The horned raptors of Sinmo Khadang and Tabo vividly recall a carved specimen at the Yaru Zampa site in Ladakh. They all have wings folded in a diamond or hooked pattern, triangular bodies and tails and what appear to be horns.* There is also another carved raptor that appears to be horned and of similar style at Yaru.† Khyung with wings folded in a diamond pattern are known from Gertse (sGer-rtse) and Ruthok.‡ The striking similarity of the Sinmo Khadang, Tabo and Yaru Zampa raptors indicates a cultural alignment. Based on this rock art, we can infer that the creators and users of these three sites possessed a mythos and religious beliefs and customs with analogous dimensions. In a generic sense these traditions can be subsumed under the label bon.

For this raptor, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 145 (fig. V.25); Thsangspa 2014, p. 22 (fig. b); n.d., Site 8-9. Thsangspa n.d., p. 22 (fig. a); Site 8-9. Bellezza 2002a, pp. 216 (fig. XI-17c), 217 (fig. XI-18c), 221 (XI-26c); January 2012 (figs. 2, 11) and November 2014 (fig. 69) Flight of the Khyung.On the ridgeline just above Sinmo Khadang are a series of old cairns that were used to mark the arrival of the seasons. This fact and the altitudinous aspect of the cave may possibly suggest that cult activities related to the heavens were carried out at this site. In any case, bon traditions are laden with heavenly phenomena and astronomical lore.

Fig. 19. A raptor with wings partially folded and pointing downward, Sumdo 2. This depiction of a bird has a long neck and hardly any body. Protohistoric period.

The cultural significance of this petroglyph is not immediately apparent. Perhaps it indicates that cultural influences from Ladakh also reached Sumdo, but it is difficult to read so much into a single carving that does not seem to be especially iconic in nature.

Fig. 20. A swastika-like carving of a bird (8 cm high), Drakdo Kiri (Brag-rdo ki-ri; el. 3180 m). Protohistoric period. This figure has a round head, upturned wings / arms and a triangular tail.

Birds that resemble swastikas are also found in the rock art of Upper Tibet,* intimating another point of cultural convergence with Spiti. There are many other figures on the same boulder, including hunting scenes.

For example, see Bellezza 2000, p. 47 (fig. 18). I will return to the swastika-birds of Upper Tibet in a future newsletter.

Fig. 21. Red ochre anthropomorph and bird, Kubum (sKu-bum; el. 4315 m). The arms of the anthropomorph almost form circles as if it is carrying something. The figure has a peaked cap and rectangular body. The type of bird represented by this long-necked specimen is uncertain. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

The approximately thirty pictographic figures at Kubum consist of anthropomorphs, swastikas, trees and the sun and crescent moon. The paired bird and anthropomorph are somewhat set off from others at the site, but it cannot be determined whether they were composed together or stand separately. If they are paired, religious or mythological factors behind their creation are indicated. Irrespective of the particular meaning that was conferred on the bird and anthropomorph at Kubum, the pictographs of the site in general betoken a mytho-ritual function within a cult setting, which might be described generically as bon.* As noted, birds are rare in the rock art of Spiti and those like the khyung have supermundane significance. That Kubum had a pre-existing religious identity is strengthened by it being selected for the construction of a retreat center by the Sakya (Sa-skya) sect of Buddhism, circa the 13th century CE. Peaked headgear like that worn by the Spiti pictographic figure is quite common in the anthropomorphic depictions of Upper Tibet.

In the Upper Tibetan region of Guge there is a rock carving of an anthropomorph consorting with a raptor. See August 2014 (fig. 19) Flight of the Khyung; Bellezza 2012 (http://www.himalayanart.org/items/31827).Birds have manifold mythological and religious functions in Tibetan literature and the oral tradition. So extensive is this material, that to provide even a synopsis would require several paragraphs and none of the traditions cited could be correlated beyond a shadow of a doubt with the rock art of Kubum. In general, the tradition of deities manifesting as birds (ornitho-theriomorphism) is probably best indicated.

3. Equids

As noted in last month’s newsletter, horses and the equestrian arts are not well represented in the rock art of Spiti. In Upper Tibet and Ladakh horses were regularly used to hunt wild yaks; however, the lower elevation rugged valleys of Spiti do not appear to have been a fecund source of wild yaks. This may be one main reason why horse riding does not seem to have become a popular activity in prehistoric Spiti. The slower pace of cultural development in Spiti (a region without large pre-Buddhist monuments) might have contributed to the deferred adoption of the riding horse. Be that as it may, the handful of equid petroglyphs in Spiti dating to the prehistoric epoch (pre-7th century CE) seems to reveal Upper Tibetan influences.

Like the tiger and horned eagle, the horse is an animal with a sacred status in Tibet. In Tibetan culture, the horse has long been the mount (chibs) of choice for numerous deities, the bearer of a good luck energy (rlung-rta), an object of divine offering (tshe-thar, lha’i rta), and a transporter of the souls of the deceased to the afterlife (do-ma), etc.

Fig. 22. Equid (25 cm long) with two swastikas above, Sumdo 2. The equid is identified by the shape of its head, neck, long tail and frame. Iron Age.

Portraits of solitary equids (horses and onagers) are rare in Spiti but quite common in Upper Tibet. Swastikas carved directly above animals are well known in Upper Tibet and Ladakh. However, two swastikas looming above a single animal is rare in Upper Tibetan rock art. The significance of the Spiti composition is not clear. The swastikas may be a solar sign, but why two of them? Perhaps then these swastikas are auspicious or protective marks or have other purposes. The functions of the swastika in Tibetan culture are particularly rich and varied (for a synopsis, see Bellezza 1997: 228–230). The swastika is the mostly common and widely occurring symbol in Spiti rock art, as it is in Upper Tibet.

The carving style of the equid from Sumdo 2 matches that used to create other early art at the site, including a khyung (see fig. 14), supporting its identification with Upper Tibetan culture. It is worth considering that this petroglyph may possibly mark the literal or symbolic introduction of the domesticated horse in Spiti, but I hasten to add that this is mere speculation.

Fig. 23. Another possible equid carving (21 cm long) from Sumdo 2. This animal is identified through its hanging wedge-shaped tail, shape of its head and overall appearance. Protohistoric period.

This appears to be another rare portrait of an equid in the rock art of Spiti (if not, it is a wild yak). It may have been created by Upper Tibetans or by natives of Spiti chronicling the culture or natural history of their highland neighbors.

Fig. 24. An archer on horseback (25 cm long) firing bow, Sumdo 2. No animals are visible in close proximity to the bowman. The figure sitting astride the horse has a round head and a body that merges with the top of the horse carving. The shape of the weapon indicates that it is a recurve bow, a technology that spread widely throughout Eurasia. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

Mounted archers are very common in Upper Tibetan hunting and war scenes and as isolated portraits. In Spiti horse riders are uncommon, particularly before the Early Historic period. The location and nature of this carving suggests Upper Tibetan cultural influences. It is hardly possible to ride horses in the gorge that forms around Sumdo without a bridle trail, and the one from historic times is situated well above the big boulder at Sumdo 2. Thus this rock art might be best seen as a demonstration of martial prowess. In any event, the introduction of horse riding in Spiti almost certainly came from Upper Tibet or Ladakh. Petroglyphs such as this one indicate that this development occurred no later than the Protohistoric period.

Fig. 25. A mounted archer (25 cm long), Sumdo 1. Many of the anatomical details of the horse and rider were rendered in this realistic carving. The horseman is in pursuit of a wild ungulate (not shown in image). Early Historic period or later.

This petroglyph is also located in the gorge at Sumdo and is a show of hunting and equestrian skills. Sumdo being a crossroads has received much traffic over the course of history, and some visitors for whatever reasons chose to embellish its rock surfaces with carvings. The great majority of petroglyphs in this locale are found at Sumdo 2. Modern road construction may well have destroyed much of the rock art of Sumdo 1.

Fig. 26. A horseman standing on his mount (13 cm long, 15 cm high), Dzamathang. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

This equestrian composition and the two to follow were carved on a large rock (3.3 m x 2.5 m) with many other carvings on the top and sides. These include wild caprids, standing archers, swastikas and geometric subjects made at various times in history. This particular petroglyph appears to be an acrobatic show of equestrian skill. The Dzamathang site straddles the old route between Hurling (Hur-gling) and Gyu (rGyu). It can be readily imagined that visitors to or from Upper Tibet were responsible for this petroglyph as well as the ones depicted in figs. 26 and 27.

Fig. 27. Horseman (17 cm long), Dzamathang. Early historic period.

Fig. 28. What appears to be another horseman (17 cm long) at Dzamathang. The rider however is not clearly discernable. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 29. The shelf at Dzamathang. The mountains of Kinnaur can be seen in the background. To the left of the shelf is the main road that connects Sumdo to Hurling.

4. Wild yaks

Compositions that depict wild yak hunting in Spiti are uncommon. On the other hand, rock art portraying riders hunting wild yaks in Upper Tibet are very common and are also well known in Ladakh. Some of the wild yak hunting scenes in these two regions closely match those of Spiti.

Fig. 30. A mounted archer (13 cm long) confronting a wild yak (15 cm long), Shelatse (Shel-la-rtse; el. 3275 m). The wild yak has the rounded horns, snout and broad tail characteristic of a wild yak. The bow of the mounted figure is discernable; he appears to be firing at its prey. Protohistoric period.

This petroglyph is southwest facing, but the orientation of petroglyphs in Spiti seems to have been largely a matter of convenience. They were placed wherever rock surfaces were conducive to their creation. There are a number of other carvings on the same boulder, including caprids, anthropomorphs and non-descript figures. This boulder is situated near the trail that connects Hurling (Hur-gling) to Gyu (rGyu) and Guge. It is not likely that wild yaks could have been hunted on horseback in such rugged terrain. The proximity of this rock art to a major line of communications suggests that Upper Tibetan influences lie behind its creation.

Fig. 31. A horseman armed with bow attacking two wild yaks, Gyurmo. The lower yak appears to have been hit with an arrow. Its horns, snout, rounded tail and belly fringe are all clearly recognizable. In addition to other characteristic anatomical features, the prominent withers of the wild yak are depicted on the upper specimen. The horseman is pointing his bow directly at the wild yaks, a graphic display of the final kill. Protohistoric period.

This hunting composition is found on the northwest side of a large boulder covered in ancient carvings. The style and orientation of the figures in this blunt depiction of the slaughtering of animals is strongly reminiscent of Upper Tibetan rock art. The boulder is located on a shelf in the narrow Gyurmo valley. Perhaps wild yaks once lived in this locale, but hunting on horseback is not represented in the prolific indigenous rock art of Gyurmo. Below Gyurmo is the route leading to Guge. These factors indicate that fig. 31 is of Upper Tibetan inspiration.

Fig. 32. The shelf on which is situated the rock art in figs. 31 and 33.

In addition to the hunting of wild yaks in Spiti, there are examples of this bovid portrayed in isolation or with other animals in non-hunting contexts. These wild yak carvings are concentrated in the easternmost rock art sites of lower Spiti; that is, in close proximity to Sumdo and the main route from there to Guge. The narrow valleys and lower elevation of this part of Spiti do not seem like ideal country for wild yaks. One would expect to have found them further up the Spiti valley. As noted, Upper Tibetan influences are indicated in this distribution of wild yak rock art in Spiti. Also, there is little or no wild yak rock art dating to the Early Historic period. This may suggest that the animal was already extinct in Spiti by that time.

Wild yak rock art in Upper Tibet is very extensive and styles of depiction comparable to those in Spiti are easy to find. In Tibet the wild yak is the most emblematic of animals, fulfilling a wide assortment of religious and economic functions. Its rarity in the rock art of Spiti suggests that it played a more marginal role in the religious and economic life of her inhabitants.

Fig. 33. A wild yak (10 cm long) on the same rock as fig. 31, Gyurmo. This animal does not appear to be the direct object of a hunt. Iron Age

This wild yak carving is found on a large, flat, west-facing panel (1.1 m x 1 m), which has around ninety figures on it, including blue sheep, ibex, anthropomorphs, swastikas and geometric designs. The inclusion of a single wild yak on this panel pullulating with figures from the Iron Age does indeed insinuate that this species was known locally. There being only one wild yak on the panel, however, suggests that it was not very common.

Fig. 34. A wild yak (30 cm long), Draknak (Brag-nag; el. 3155 m). The major physical traits of this species are well depicted in this petroglyph. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

On the same boulder as the wild yak are several blue sheep and an ibex from the same phase of rock art. These animals were carved on the southwest side of the rock (see July 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 2).

Fig. 35. The broad tail and shape of the horns seem to identify this carving as a wild yak (16 cm), Hurling Pharke (Hur-gling phar-ke; el. 3210 m). Iron Age or protohistoric period.

The wild yak and an ibex (not pictured) are situated on the southwest side of the boulder. On the southeast side of the same boulder are around fifty figures including many blue sheep and ibex as well as bowmen, geometric subjects and other figures.

Fig. 36. A wild yak (28 cm long), Sahal Thang (Sa-skal thang; el. 3215 m). Typical physical features of this bovine species are reproduced in this petroglyph. Protohistoric period.

This carving is one of two or three wild yaks found on a large boulder (6.2 m x 1.6 m x 1.5 m). One specimen is situated just below the wild yak pictured here. These wild yaks are not being hunted. There are many blue sheep and other figures on all sides of this boulder as well.

Fig. 37. A view of the eastern portion of the Sahal Thang site from across the Spiti river.

Fig. 38. Portrait of what appears to be a wild yak (20 cm long), Lari Tingjuk (La-ri ting-mjug; el. 3255 m). Although this petroglyph is not much more than a stick figure, its horns, head and tail are very much yak-like. Protohistoric period.

5. Cervids

Cervid rock art is uncommon in Spiti. Deer may have once ranged in Spiti but they no longer thrive there. Cervid rock art is widespread in Upper Tibet but not so common in Ladakh. This seems to suggest that the high dales of Upper Tibet were once ideal breeding grounds for the white-lipped deer (Cervus albirostris) and Tibetan red deer (Cervus elaphus wallici), species still found on the periphery of the region. Deer occupy a storied place in Tibetan culture. They have both divine and demonic forms and are represented in a wide spectrum of ritual practices, especially those of a non-Buddhist nature. According to Tibetan archaic funerary texts, deer once functioned as protectors and psychopomps of the dead.

Fig. 40. A deer (20 cm long) portrait, Drakdo Kiri. The large branched antlers pinpoint this petroglyph as that of a cervid. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

This deer carving is not unlike some of those in Upper Tibet.

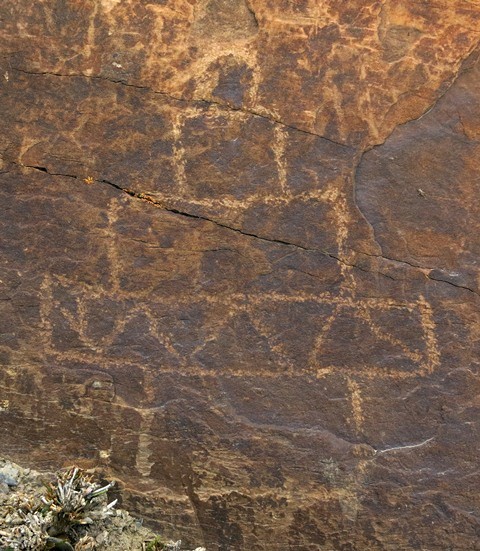

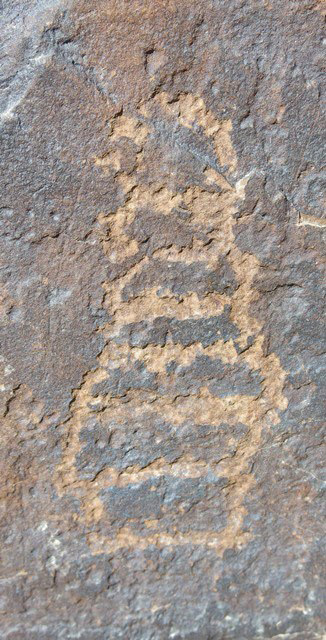

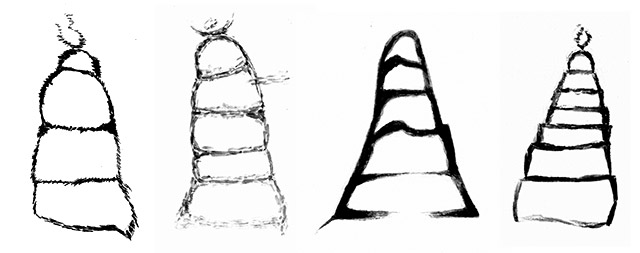

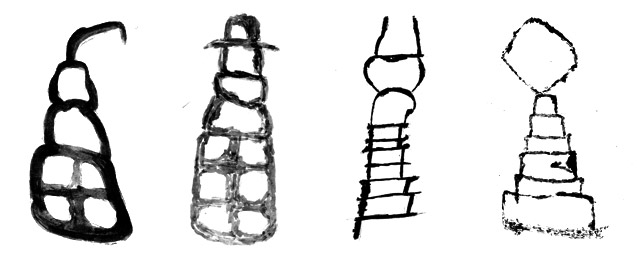

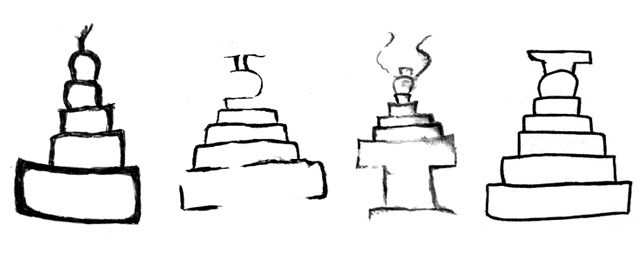

6. Ceremonial structures

Ceremonial structures corresponding to those in Upper Tibet and Ladakh are well represented in the rock art of Spiti. These are likenesses of rudimentary stepped shrines or tabernacles for deities and more complex tiered constructions known in Tibetan as chorten (mchod-rten). The most common types of shrines in the rock art of Greater Western Tibet consist of three to five graduated levels, some of which are topped by a spherical structure and / or a mast. According to Yungdrung Bon tradition, stepped shrines called lhaten (lha-rten) originated in Zhang Zhung for the propitiation of deities such as Gekhö (Ge-khod; Bellezza 2008: 252–258). While these accounts cannot be verified, the archaeological and rock art evidence indicates that such ritual monuments were built in Upper Tibet in the Protohistoric and Early Historic periods.*

Shrines, some of which are stepped, are still erected in contemporary Greater Western Tibet and are known as lhatho (lha-tho), lhatsuk (lha-gtsug), sekhang (gsas-khang) sekhar (gsas-mkhar), tenkhar (rten-mkhar), chokhar (lcog-mkhar), lhakhang (lha-khang), tsenkhang (btsan-khang) and lukhang (klu-khang). These types of structures serve as tabernacles and as ritual venues for the propitiation of territorial and ancestral spirits.

Over the last two decades, I have documented more than 200 shrines and chortens in the rock art of Upper Tibet that appear to predate the 11th century CE. They come in a number of forms and styles. In Spiti more than forty have come to light, with the largest concentration at Lari Tingjuk.† It is not difficult to differentiate primitive shrines from elaborate chortens in rock art; however, there are many transitional styles, and it is not always possible to distinguish what class of ceremonial object is intended.*

For likenesses of primitive ceremonial structures in the rock art of Upper Tibet, which come in a variety of forms, painted and carved, see Bellezza 1997, p. 181 (fig. 1); 2000, p. 53 (fig. 33); 2001, pp. 341 (fig. 10.45), 366 (figs. 10.94, 10.95); 2002a. pp. (fig. XI-4a), 200 (fig. XI-5a), 201 (fig. XI-6a), 202 (fig. XI-7a), 248 (fig. XI-10g), 257 (fig. XI-2k); 2008, pp. 182 (figs. 335), 183 (figs. 336, 337), 184 (figs. 334, 342); 2014a, p. 445 (fig. THE7.3). For an example of a tiered shrine in the rock art of eastern Tibet, see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 169 (fig. 234).For chortens in the rock art of Upper Tibet, see Suolang Wangdui 1994, pp. 143 (fig. 178), 146 (fig. 184); Bellezza 1997, pp. 184 (figs. 4, 5), 207 (fig, 26); 2000, pp. 41 (figs. 4–6), 49 (fig. 23), pp. 339 (figs. 10.40, 10.41), 340 (figs. 10.42, 10.43), 341 (fig. 10.44), 342 (figs. 10.46, 10.47), 350 (10.62), 367 (figs. 10.96, 10.97), 368 (figs. 10.98, 10.99), 369 (figs. 10.100, 10.101), 370 (figs. 10.102, 10.103), 371 (figs. 10.104, 10.105); 2002a, p. (figs. XI-8a, 9a), 208 (fig. XI-1b), 248 (fig. XI-11g), 249 (figs. XI-12g, 13g), 250 (XI-14g, 15g), 254 (XI-1j), 256 (XI-5j); 2008, pp. 160 (figs. 266, 267), 184 (figs. 338–341), 185 (figs. 343–347); August and October 2013 and July 2014 Flight of the Khyung. Thakur (2001: 33 [pl. 3]; 2008: 30 [fig. 8]) provides illustrations of several tiered shrines carved on boulders. They appear to have been destroyed.Comparable stepped shrines and chortens have been discovered in Ladakh, northern Pakistan and Wakhan.* Archaic shrines in the rock art of Spiti are most like their counterparts from Upper Tibet, suggesting that, as in other areas of rock art we have been exploring, these two regions shared a common religious heritage in the Protohistoric period; specifically, that in which stepped structures played a part.

On those from Indus Kohistan, see Thewalt (http://www.thewalt.de/chilas1.htm); Bruneau 2007; Jettmar 1982; 1985. For Ladakh: Bruneau 2010, figs. 86, 105 (a vase?), pl. 53, pl. 54, pl. 88–90, pl. 114, Francke 1902; 1903; 1905b; Orofino 1990; Linrothe. For Gilgit and Wakhan: Mock 2013, pp. 12, 15.Chortens are a well-known religious monument of Tibetan Buddhism and Yungdrung Bon, corresponding with the Indian stupa. They serve a variety of purposes such as models of the universe and the five elements, foci for the descent of deities, protective and auspicious additions to the landscape, representations of the Buddha and religious doctrines, and reliquary vessels. The archaeological, rock art and textual records indicate that these types of monuments began to be created in the Early Historic period. They continued to be made in an unbroken historical tradition that extends to the present day.

The origins of rock art chortens in Upper Tibet can be attributed to two disparate cultural streams: 1) the diffusion of Buddhist art and architecture from Gandhara and Kashmir to Indus Kohistan and Ladakh, thence to Upper Tibet; 2) pre-existing native ceremonial constructions and art in Greater Western Tibet (Bellezza 2002: 128, 129; 2008: 182–186; 2014c: 189–192).

The chortens of Spiti are comparable to more elementary styles from Upper Tibet, Ladakh and northern Pakistan. This indicates that rock art traditions influenced by Buddhist art and architecture reverberated through cultures of the Greater Western Himalaya. The chorten rock art of Spiti is liable to be the product of Upper Tibetan and possibly Ladakhi transmissions into the region in the Early Historic period. Had Gandharan stupa art and architecture or their historical derivatives reached Spiti directly through the lower reaches of Himachal Pradesh, there should be definite evidence of this in the rock art record, but there are no indications of such contact.

The exquisitely carved ornate Buddhist chortens of Indus Kohistan, Baltistan and Ladakh are not known in Spiti and are hardly met with in Upper Tibet before the 11th century CE. This actuality along with other rock art, archaeological and epigraphic evidence indicates that penetration of Buddhism into Spiti and Upper Tibet was relatively weak before the dawn of the second millennium CE. Most of the rock art chortens of Spiti and Upper Tibet of the Early Historic period appear to have been made by those professing non-Buddhist or bon religious affiliations (as testified by the presence of peculiar design traits as well as the presence of counterclockwise swastikas, wild ungulates and non-Buddhist inscriptions in the same compositions).

The purview of shrine and chorten styles in Spiti rock art is not as wide as in Upper Tibet or Ladakh. In fact, there are few fully fledged chortens in Spiti attributable to the Early Historic period. This appears to be another indication that the culture of Spiti was not as progressive as that of its neighbors on the Tibetan plateau. Spiti was a frontier region sandwiched between the high plateau and Himalayan valleys, one evidently shunted off from some of the cultural and technological developments unfolding in other parts of Greater Western Tibet, a state of affairs that continued into the Early Historic period.

Shrines

Fig. 41. A shrine or tabernacle of three tiers with a rounded top section (17 cm high), Lari Tingjuk. The lower three rectangular levels are divided into two sections each. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 42. A shrine of three tiers (the top one is somewhat rounded; 11 cm high) and accompanying ibex, Gyari (rGya-ri; el. 3230 m). Protohistoric period.

As was noted in last month’s newsletter, ibex horns are still erected on lhatho shrines in Spiti. This composition shows that the association shrines and the ibex is of considerable antiquity.

Fig. 43. A view of the Gyari site looking up the side valley belonging to Sumra village.

Fig. 44. A shrine with a triangular form divided into of four tiers (12 cm high) and counterclockwise swastika carved on top of a boulder, Lari Tingjuk. On top of the same boulder are geometric designs. Protohistoric period.

The religious nature of the two figures in this composition are self-reinforcing.

Fig. 45. A shrine of three graduated levels with rounded top (bum-pa), Tsentsalap (rTsan-rtsa leb; el. 3230 m). Protohistoric period. On the same west facing side of the boulder are other rock art figures.

Fig. 46. A view of the Tsentsalap rock art site.

Fig. 47. A shrine of two tiers and rounded top section (bum-pa) with circles protruding from the base (11 cm high), clockwise swastika and ungulate, Poh Thangka (el. 3440 m). Early Historic period.

Fig. 48. A shrine of three rectangular tiers topped by a sphere (12 cm high), Poh Thangka. The upper sections of this carving have been retouched. Early Historic period.

Shrines of the same style are found in rock art as far away as Lake Nam Tsho (gNam-mtsho) in Upper Tibet.

Fig. 49. A two-stepped shrine with hemispherical top portion (8 cm high) and horseman deeply carved into the rock, Poh Thangka. Probably Protohistoric period.

Perhaps the horseman is a self-portrait and the shrine his offering or protective device.

Fig. 50. A view of the Poh Thangka rock art site.

Fig. 51. A shrine of four graduated levels and bulbous top (22 cm high), Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 52. Two shrines; one with five tiers and rounded top (16 cm high) and one with two or three tiers and rounded top, Sahal Thang (Sa-skal-thang). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 53. A shrine of five tiers (12 cm high) carved on top of a boulder, Lari Tingjuk. This petroglyph closely resembles fig. 44 in form. On the top of the same boulder are two suns. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 54. A shrine of seven tiers, Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 55. A shrine of six tiers with half circle extending down from the base (25 cm high), Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 56. A shrine of four tiers (20 cm high), Lari Tingjuk. This one was bisected into two halves. Protohistoric period.

Transitional Forms

Fig. 57. A shrine or chorten of six or seven tiers (at least 17 cm high), Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 58. A shrine or chorten of four rectangular layers and round top (bum-pa), Shelatse (Shel-la-rtse; el. 3240 m). Protohistoric or Early historic period. This carving was retouched.

Fig. 59. A view of the Shelatse site.

Fig. 60. A shrine or chorten with four graduated levels and a rounded top with mast, Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric or Early historic period.

Fig. 61. Two shrines or chortens of seven and three layers (58 cm and 33 cm high) on south-facing rock face, Shelatse (el. 3310 m). The round top or bumpa can be seen in the specimen on the left. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 62. Shrine or chorten with five tiers (the second from the bottom is overlapping) and tiny surmounting sphere or bumpa on top (9 cm high), en route to Gyurmo (el. 3260 m). Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 63. Shrine or chorten with four tiers and small bumpa (38 cm high), Gyurmo (el. 3360 m). Note the band of triangles in the overlapping level. Protohistoric or Early Historic Period.

Fig. 64. Two shrines or chortens (20 cm and 23 cm high) in style similar to specimen in fig. 63, situated on the same southwest face of the boulder, Gyurmo. Early Historic Period.

In all three specimens on this boulder the second layer from the bottom overhangs the base.

Fig. 65. A shrine or chorten of six tiers surmounted by a bumpa, Lari Tingjuk. Early Historic period.

This is one of three comparable ceremonial structures carved on the same boulder. They are each 15 cm to 30 cm in height. Two similar structures (tall, slender, with six or more tiers and rounded top) are found on another boulder at the Lari Tingjuk site. These specimens are highly worn and re-patinated and may date to the Protohistoric period. They are now hard to distinguish. Each of them is around 50 cm in height.

Chortens

Fig. 66. A multi-tiered chorten (58 cm high), Shelatse. The tiny bumpa and triangular spire (’khor-lo) identify this as an archaic form of the monument. A smaller multi-tiered chorten is located to its right. They are found on the south-facing vertical face of a boulder and are both highly eroded. Early Historic period. There is an older ibex carving above the larger chorten.

Another multi-tiered chorten (35 cm in height) of comparable form and age is found at Lari Tingjuk, but it is more highly worn and hard to see.

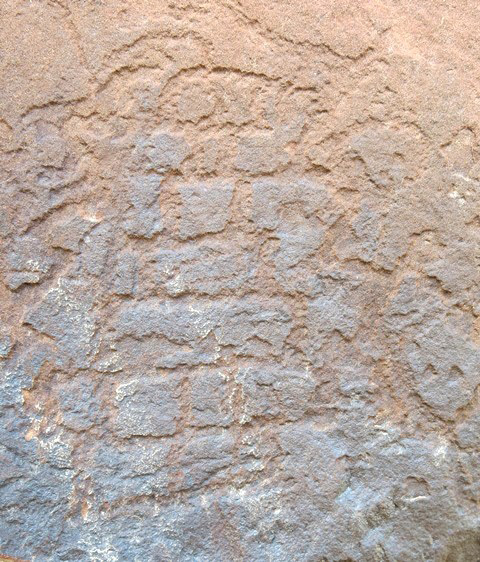

Fig. 67. Three stepped shrines probably of the Protohistoric period and a fully developed chorten (35 cm high) of the Early Historic period, Dzamathang. The three older ceremonial structures are of types (stylistically and technically) we have already examined. Near the top of the photograph is a wild yak exhibiting similar wear and re-patination qualities. A more refined technique of engraving was used to produce the chorten. Below the bumpa is a half-circle layer and below that four rectangular layers. One level is segmented by straight and diagonal lines and another level by diagonal lines only. Above the bumpa extend three vertical lines. A flower of six petals was engraved with the same technique as the chorten. By its paleographic characteristics, an inscribed Om in the upper left-hand side of the photograph was produced either in the Early Historic or Vestigial period. The four swastikas are of more recent production.

The three-pronged crown is a common kind of finial in rock art depictions of ceremonial structures in Upper Tibet, but this is the only example documented in Spiti. The equivalent finial in Yungdrung Bon is known as the ‘horns of the bird, sword of the bird’ (bya-ru bya-gri), a sign of the superlative nature of the religion.

Fig. 68. Three chortens, Tibetan letters and caprids, Tabo. This boulder was integrated into the wall of an apple orchard, saving it from total destruction. Two of the chortens have five levels and the one on the left has three levels. Early Historic period.

Many other boulders with rock art in the vicinity were not so lucky. Each of the three chortens was rendered in a different style. The two specimens with heart-shaped finials are comparable to examples in Ladakh.

Fig. 69. Six (one is incomplete) of nine or ten chortens aligned in a horizontal row, each rendered in a different style (12 to 15 cm in height), Shelatse. These chortens were lightly etched in the rock. Early Historic or Vestigial period.

Fig. 70. Three multilayered chortens, Tibtra. Early Historic or Vestigial period. Photograph courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

These three chortens were documented subsequent to my 2015 expedition to Spiti. There is also a chorten etched in the big boulder at Sumdo 2 and one at Lari Tingjuk, which may predate the 11th century CE. Chorten carvings postdating the 10th century CE will be studied in the November newsletter.

Fig. 71. Black and white drawings of shrines and chortens in the rock art of Upper Tibet resembling those found in Spiti. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods. By Lingtsang Kalsang Dorjee and his atelier.

Fig. 72. Black and white drawings of shrines and chortens in the rock art of Upper Tibet resembling those found in Spiti. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods. By Lingtsang Kalsang Dorjee and his atelier.

Fig. 73. Black and white drawings of shrines and chortens in the rock art of Upper Tibet resembling those found in Spiti. Protohistoric and Early Historic periods. By Lingtsang Kalsang Dorjee and his atelier.

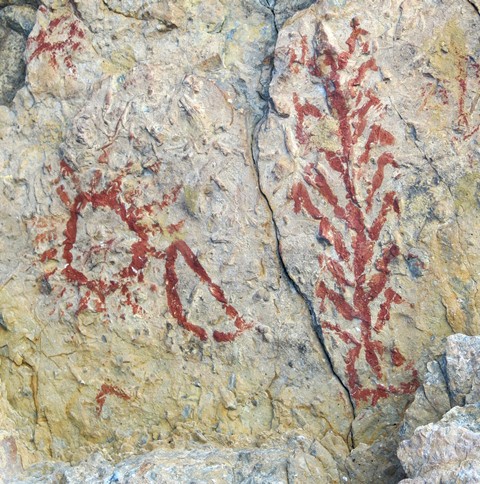

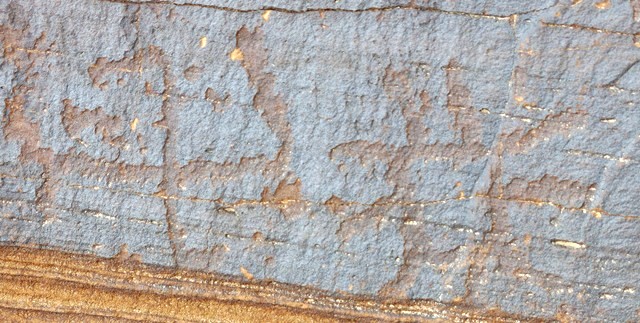

7. Symbolic compositions

In Upper Tibet and Ladakh rock art, S-shaped and scroll designs are sometimes carved in isolation on rocks.* In the rock art of Spiti more complex curvilinear designs including spirals are well represented. In all three regions these types of curvilinear subjects are of substantial antiquity, dating to the Iron Age and Protohistoric period. Curvilinear designs comparable in form and age are also known in the rock art of Mongolia and Xinjiang. While the meaning behind these kinds of curvilinear designs is a matter of speculation, it appears that they served as a trans-regional symbolic and/or esthetic currency in various cultures of antiquity.

In many regions of Inner Asia S-shaped designs, volutes and scrolls ornament the bodies of wild ungulates and other animals as part of localized branches of the Eurasian animal style. This rock art is datable to the Iron Age and Protohistoric period. This style of ornamentation is not encountered in the zoomorphic art of Spiti.

Fig. 74. A scroll design (27 cm long), Gyari. Iron Age.

Fig. 75. Two scrolls on small boulder, Gyari. Iron Age.

Fig. 76. Several scrolls on the southeast side of a boulder, Lari Tingjuk. Protohistoric period.

The repeated articulation in rock art symbols or ideograms as carvings and paintings serve as a testament to what was once considered significant. They are thus an important index of ancient cultural activity. Moreover, compositions that appear to encapsulate particular abstract cultural information are crucial for cross-cultural comparisons.

A composition that almost certainly has rich symbolic meaning in Spiti and Upper Tibet, irrespective of its literal signification, is comprised of the sun, crescent moon and swastika. That these three types of figures, each with a distinctive form, were selected to be depicted together in integral symbolical formats alludes to vibrant cultural interactions between these two regions. The rock art record indicates that these channels of shared ideological representation were in operation by the Protohistoric period.

Sundry meanings and capacities are assigned the sun, moon and swastika in Yungdrung Bon and Tibetan Buddhism, but it is not easy to attribute any of these particularized traditions to rock art. From the preponderance of textual data, we might hypothesize that sun, crescent moon and swastika compositions had cosmogonic, cosmological or protective functions and served as markers of religious affiliation.

Fig. 77. Large counterclockwise swastika accompanied by sun and crescent moon, Poh Thangka. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 78. Crescent moon, sun and counterclockwise swastika, Guge. Protohistoric period.

Despite commonalities in abstract expression, these triadic compositions are rendered differently in Spiti and Upper Tibet, underscoring regional cultural and artistic differences that characterize the majority of rock art in these two regions.*

For other examples of the sun-moon-swastika composition in Upper Tibet, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 112 (fig. II.10); Bellezza 2001, p. 358 (fig. 10.78); 2008, pp. 165 (fig. 278), 166 (fig. 282), 175 (fig. 310); September 2010 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 1, 2.There are also simpler symbolic compositions in Spiti consisting of the sun and moon with and without a tree. In Upper Tibet and Ladakh we also find pre-Buddhist compositions of the sun and crescent moon.* Trees of similar design to those in Spiti pictographs are represented in Upper Tibetan rock art. These trees resemble a maize stalk: straight trunk and multiple branches that extend diagonally upward before bending sharply downward towards the ends. Some of the trees of Spiti and Upper Tibet have a small triangular base, an idiosyncratic design feature. The tree is another fertile symbol in Tibetan literary and textual traditions, one having cosmogonic, cosmological and genealogical connotations.

For sun and crescent moon compositions in the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh, see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 158 (figs. V.49, V.50); Bellezza 2002a, pp. 211 (XI-7c), 219 (fig. XI-22c), Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 103 (fig. 95). Eight such compositions are known in Ladakh and a greater number in Upper Tibet (Bruneau and Bellezza 2013: 71, 72)

Fig. 79. Sunburst and crescent moon, Draknak. Much of the veneer that formed on this petroglyph has been stripped away. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 80. Sunburst, crescent moon and tree, Kubum. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

Fig. 81. A view the rock ceiling on which fig. 78 is situated. There are a number of swastikas and trees among these pictographs as well as the bird and anthropomorph of fig. 21. Protohistoric or Early Historic period.

While the various pictographs of Kubum may have been painted by different hands, they belong to the same timeframe and express common mythic and religious themes. By virtue of their inclusion, the symbolism of the triadic sun, moon and swastika is probably subsumed in this array of pictographs.

Fig. 82. A portion of a panel of red ochre pictographs at Lhari Drakphuk, Upper Tibet. Clearly visible in a deep red ochre hue is a sunburst, crescent moon and tree. Protohistoric period.

The sunbursts, crescent moons, swastikas and trees of Kubum, Sinmo Khadang and Nyima Loksa in Spiti recall red ochre pictographs at Domar (rDo-dmar) and Lhari Drakphuk (Lha-ri brag-phug) in Upper Tibet.* Although Kubum and Lhari Drakphug are separated by more than 1000 km, they contain analogous pictorial representations. This is indicative of a corpus of cult tradition possessing various mythological, ritual and ideological elements in common. Sunbursts, swastikas, crescent moons and trees were likewise carved on a boulder at Ngondong (sNgon-gdong), Upper Tibet (Suolang Wangdui 1994: 128 [fig. 149]; Bellezza 2008: 165 [fig. 278]).

For these two sites, see Suolang Wangdui 1994, pp. 94 (fig. 180), 134 (fig. 161); Bellezza 2002a: 254 [fig. XI-1j]); 2008, p. 165 (fig. 274).The precise cultural-historical factors that led to the creation of a body of interrelated symbolic rock art are unknown. The existence of this art in widely divergent areas of Greater Western Tibet suggests that specific cult traditions with an expansive organizational ambit were operating in the Protohistoric period. Although the archaeological record documents a good deal of cultural variability in this huge region, there may have been a strengthening or codification of shared mythological, ideological and ritual structures in that period.

Perhaps it is to these common traditions, as reflected in the same repertoire of symbols painted in caves, that the term bon is best applied. While there is no archaeological evidence for the introduction of an entirely new religious order in Upper Tibet and Spiti in the Protohistoric period, major developments in the institutional apparatus of Greater Western Tibetan religion cannot be ruled out.

In Spiti there are also compositions featuring the sun and swastika and crescent moon and swastika. These appear to be full of symbolic meaning. In various configurations the same symbols have much currency in the rock art of Ladakh and Upper Tibet.*

For a petroglyph consisting of a sunburst and swastika in Upper Tibet, see Suolang Wangdui 1994, p. 113 (fig. 114).

Fig. 83. Swastika and and sunburst, Poh Thangka. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 84. Two red ochre swastikas and crescent moon (each 10 cm in height), Nyima Loksa Phuk (Nyi-ma log-sa phug; el. 4330 m). Protohistoric period.

Fig. 85. The Nyima Loksa Phuk site is situated high up in the rocks on the right side of the ravine.

Fig. 86. Red ochre composition of crescent moon and swastika, Sinmo Khadang. In close proximity are other pictographs, including a swastika, tree and circles. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 87. The east mouth of the Sinmo Khadang cave site.

Nyima Loksa Phug means the ‘Cave of the Reversal of the Sun’. According to local tradition, this cave marks the return of the sun’s northern trajectory at the time of the winter solstice. As already mentioned, on the ridgeline above the cave of Sinmo Khadang there are calendrical cairns used in premodern times. Thus astronomical lore is attached to Nyima Loksa Phug and Sinmo Khadang. How this might be related to the ancient pictographs is unclear. That there may be some connection is also hinted at by their high altitude locations.

Fig. 88. Swastika (6 cm) and crescent, Lari Thangmoche (La-ri thang-mo-che; el. 3270 cm). Protohistoric period. The circle to the left of the swastika (probably representing the sun) appears to have been added later, perhaps in response to Upper Tibetan cultural influences.

Here we have another example of the symbolic vocabulary of upper Spiti pictographs found in the carvings of lower Spiti, highlighting the coherent cultural complexion of the region.

Fig. 89. Tree (18 cm high) at Nyima Loksa. Note its triangular base. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 90. Tree carving (35 cm high), Sumdo 2. Protohistoric period.

Fig. 91. Two opposing swastikas, Tabo, Forest Research Center (el. 3305 m). Protohistoric period.

Confronted swastikas, each oriented in different directions are found at several sites in Upper Tibet.* Painted together or at separate times, they appear to be laden with symbolic meaning. In Upper Tibet of the Vestigial period, they sometimes chronicle encounters between different religious traditions or sects, a positive one in the case of two pictographs at Tara Marding (rTa-ra dmar-lding; Bellezza 2008: 163 [fig. 273]) and a confrontational one at Nam Tsho (Bellezza 2000: 44 [fig. 13]). The older example in Spiti seems to be a harmonious composition, indicating the complementarity of the two orientations of the swastika.

See Bellezza 2000, pp. 44 (fig. 13), Bellezza 2008, p. 163 (fig. 273).

Bibliography

Bellezza, John V. 2014a. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Residential Monuments, vol. 1. Miscellaneous Series – 28. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org), 2011: http://www.thlib.org/bellezza

____2014b. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Ceremonial Monuments, vol. 2. Miscellaneous Series – 29. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org), 2011: http://www.thlib.org/bellezza

____2014c. 2014. The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

____2013. Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet: Archaic Concepts and Practices in a Thousand-Year-Old Illuminated Funerary Manuscript and Old Tibetan Funerary Documents of Gathang Bumpa and Dunhuang. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 454. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

____2012. “Before the Mural and Scroll Painting: Rock Art in Ancient Tibet”, in Himalayan Art Resources http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=3108

____2011. “Territorial Characteristics of the Pre-Buddhist Zhang-zhung Paleocultural Entity: A Comparative Analysis of Archaeological Evidence and Popular Bon Literary Sources”, in Emerging Bon: The Formation of Bon Traditions in Tibet at the Turn of the First Millennium AD (ed. H. Blezer), pp. 51–116. PIATS 2006:Proceedings of the Eleventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Königswinter 2006. Halle: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies GmbH.

____2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

2005. Calling Down the Gods: Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet, Tibetan Studies Library, vol. 8,Leiden: Brill.

____2002a. Antiquities of Upper Tibet: An Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Sites on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

____2002b. “Gods, Hunting and Society: Animals in the Ancient Cave Paintings of Celestial Lake in Northern Tibet” in East and West, vol.52 (1–4), pp. 347–396. Rome: IsMEO.

____2000. “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet” in Rock Art Research, vol. 17 (no. 1), pp. 35–55. Melbourne.

____1997. Divine Dyads: Ancient Civilization in Tibet, Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

Bruneau, Laurianne. 2013. “L’art rupestre du Ladakh et ses liens avec l’Asie centrale protohistorique”, in Cahiers d’Asie Centrale – Archéologie française en Asie centrale post-soviétique: un enjeu sociopolitique et culturel (ed. Bendezu-Sarmiento), pp. 487–498. Tashkent: IFEAC, Tashkent.

____2010. “Le Ladakh (état de Jammu et Cachemire, Inde) de l’Âge du Bronze à l’introduction du Bouddhisme : une étude de l’art rupestre. Tome 3. Répertoire des pétroglyphes du Ladakh”. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris I-Panthéon-Sorbonne.

____2007. “L’architecture bouddhique dans la vallée du Haut Indus (Pakistan): un essai de typologie des représentations rupestres de stūpa”, in Arts Asiatiques, no. 62, pp. 63–75.

Bruneau, Laurianne and Bellezza John V. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

Bruneau, L. and Vernier, M. 2010. “Animal style of the steppes in Ladakh: a presentation of newly discovered petroglyphs”, in Pictures in Transformation : Rock art Researches between Central Asia and the Subcontinent (L. M. Olivieri et al.), pp. 27–36. Oxford: BAR International Series 2167. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Chen Zhao Fu. 1996. Zhongguo yanhua quanji – Xibu yanhua 1 (The Complete Works of Chinese Rock Art – Western Rock Art Volume 1), vol. 2. Shenyang, Liaoning meishu chubanshe.

Francfort Henri-Paul. 2002. “Rock Art on the Rocks; Rock Art off the Rocks: Iron Age Petroglyphic Images and Agricultural Societies in Xinjiang and Bactria”, in Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, vol. 4 (no. 12), pp. 61–73.

____1994. “Les pétroglyphes d’Asie Centrale et la Route de la Soie”, in Les routes de la soie, Patrimoine Commun, identités plurielles, pp. 35-52. Paris: Éditions Unesco.

Francfort, H.-P., Klodzinski, D., Mascle, G. 1992. “Archaic petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar” in Rock Art in the Old World. Papers presented in Symposium A of the AURA Congress, Darwin Australia. 1988 (ed. M. Lorblanchet), pp.147-192. Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

Francke, August H. 1905a. The Story of the Eighteen Heros. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

___ 1905b. “Archaeological notes on Balu-Mkhar in western Tibet” in Indian Antiquary. A Journal of Oriental Research, vol. 34, pp. 203–210. Bombay.

___ 1903. “Some more rock-carvings from lower Ladakh” in Indian Antiquary. A Journal of Oriental Research, vol. 32, pp. 361–363. Bombay.

___ 1902. “Notes on rock-carvings from lower Ladakh” in Indian Antiquary. A Journal of Oriental Research, vol. 31, pp. 398–400.

Karmay, Samten G. 1972. The Treasury of Good Sayings. A Tibetan History of Bon. Reprint, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2001.

Jettmar, Karl. 1985. “Non-Buddhist traditions in the petroglyphs of the Indus valley” in South Asian Archaeology. 1983, vol.2, (eds. J. Schotsmans and M. Taddei), pp. 751–778. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale.

____1982. Rock carvings and Inscriptions in the Northern Areas of Pakistan. Islamabad: Institute of Folk Heritage.

Linrothe, Rob. “Rock Art of the Hiamlayas, Tibet and Central Asia”, in Himalayan Art Resources. Accessed August 6, 2015.

http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=785