January 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

Happy New Year to the fliers of the great khyung! May 2013 bring you all much joy and success. This month’s Flight of the Khyung highlights rock art discoveries made in the last weeks of 2012, in the eastern Changthang. Fresh down from the high plateau, this art is presented here for the first time. Among the finest finds were an undocumented pictographic site and archaic lakeside cave shelters. It reminds us how much there still is to explore in Tibet. In addition to rock art, we will look at an amazing ancient sculpture revealed by Tibetans for the first time in a generation.

High on the khyung

Some of you admirers of the great horned eagle will remember that last January’s newsletter showcased ancient khyung rock art from Upper Tibet. Same this year, but firstly, for your inspection, here is an unusual inscription expressing the most exhilarating of sentiments.

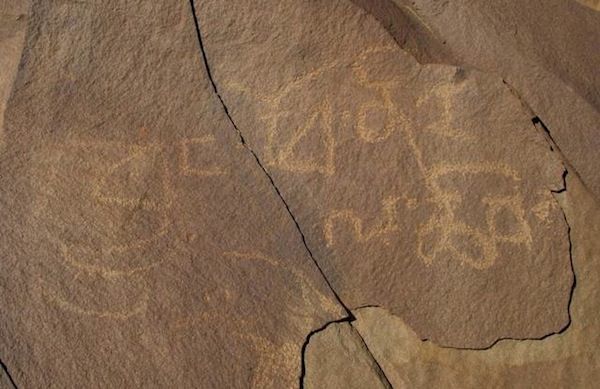

Fig. 1. Ancient inscription from northwestern Tibet documented in 2011 on the UTRAE II.

This inscription may possibly read: khyung pho ni nga la chib. If so, it could be translated as “The male khyung is that on which I ride”. Despite this reading being attractive and suggestive of dzokchen (rdzogs-chen), an esoteric mind-training tradition, it is not very sound grammatically speaking. Also, it rests on the fourth syllable being rendered as nga, although it was inscribed differently from the nga in ‘khyung’, raising more doubts. Reading the fourth syllable as ra (goat) instead, could change the sentence to: “The male khyung is that which rides on the goat”. However, this reading does not make too much sense to me. Interpreting khyung-pho as a clan name (Classical Tibetan = khyung-po) alters the sentence to: “The Khyung-pho [clan] is that which rides on the goat”. If this was the intended meaning of the writer, it may convey that the goat was a symbol or mount of the clan deity of the Khyung-pho. In modern Upper Tibet, there are still rituals in which goats function as vehicles for the protective spirits of ancient clans, adding some weight to this reading. Truth be told, I cannot say for certain what the writer actually intended his (yes, I think a male composed it) inscription to mean. This level of ambiguity is frequently encountered in short epigraphs written in Old Tibetan (unless they are simple dedications, prayers or mantras), for there is no wider textual context upon which to rely for teasing out their meaning.

The style of writing with its blocky letters, horizontal i superscriptions and uneven arrangement of syllables suggests an early historic period (650–1000 CE) origin. This chronological attribution based on paleographic grounds is strengthened by the old-fashioned usage of pho (an affix signifying ‘male’) with khyung and the obsolete spelling chib (to mount, to ride; Classical Tibetan = bcibs). Also, the engraved letters have undergone considerable re-patination, another sign of much age. The Bon religion holds that dzokchen is of prehistoric origin, but the oldest texts of this tradition date to the early historic period. We require more archaeological evidence to properly evaluate this claim of great antiquity.

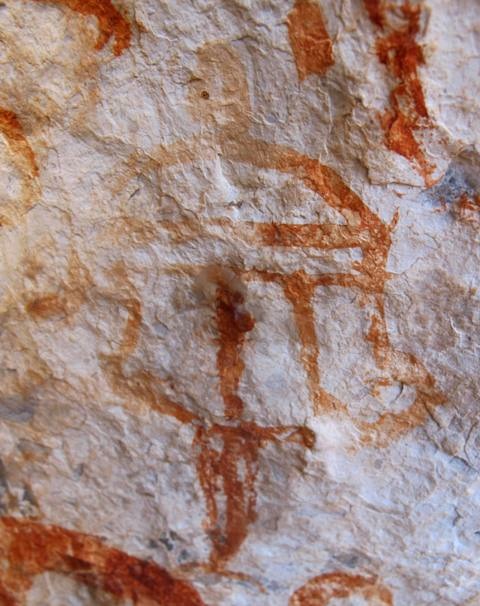

Fig. 2. A red ochre raptor with prominent horns found at a newly documented rock art site, eastern Changthang. This pictograph (20 cm in height) has undergone much wear and geochemical change necessitating rigorous digital enhancement in order to fully appreciate its beauty.

In Upper Tibet rock art the horned eagle or khyung varies much in style and age (for some examples, see January 2012 newsletter). This particular specimen is beautifully and vividly rendered, reflecting the cultural iconic status of the khyung. Painted in isolation, it is difficult to pinpoint the age of this lovely pictograph. It is best attributed to either the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE) or early historic period.

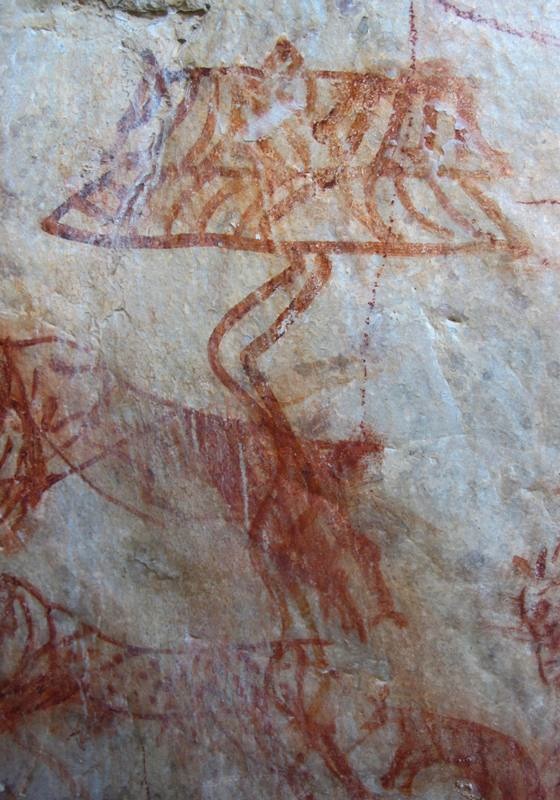

Fig. 3. Another horned raptor from the eastern Changthang documented last December.

This specimen belongs to an early phase of rock art filling a small but important cave. This rock art is characterized by thin lines, sharp angles, embellished bodies, and an economic but vibrant style of painting. The khyung appears to date to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) or protohistoric period. The existence of such rock art seems to verify the prehistoric origin of the khyung, as maintained by Bon texts and the oral tradition. These sources introducing horned raptors, however, may be at some variance with the identity and function of those painted and carved on stone.

An ancient stone figure from western Tibet

We now turn to a rare stone sculpture of exceptional historical and artistic value. I heartily thank my Tibetan colleagues Dondrup Lhagyal and Karma Gyaltsen for letting me know that this sculpture was recently stripped down to its original state.

Fig. 4. The stone sculpture at Khardong (Mkhar-gdong) identified by the Bonpo as that of the 8th century CE saint and translator Dranpa Namkha (Dran-pa nam-mkha’). Khardong, in western Tibet, is the site of what may well have been a capital of Zhang Zhung, Khyunglung Ngulkhar (Khyung-lung dngul-mkhar), the ‘Horned Eagle Country Silver Castle’. For more information on this location, see April 2012 newsletter. Photo courtesy of Dondrup Lhagyal.

According to the historical tradition of Gurgyam (Gur-gyam), the Bon monastery located at the foot of Khardong, the site was neglected for centuries. It is said that, circa 1930, the renowned lama Khyungtrul Jikme Namkha Dorje (Khyung-sprul ’jigs-med nam-mkha’ rdo-rje) unearthed the stone statue from the top of the Khardong formation. He identified it as the self-arising image of the Bon sage Dranpa Namkha and considered that it marked the location of the capital of Zhang Zhung. The Bon call the statue Kharak Doku Rangjung (Kha-rag rdo-sku rang-byon), the ‘Self-formed Stone Personage of Kharak’ (a region of Zhang Zhung).

Khyungtrul believed that the damaged sculpture had been desecrated during the persecution of the Bon religion in the late 8th century CE. He restored it for religious purposes by rebuilding the missing parts and covering the whole statue with a clay veneer to recreate facial and other anatomical details. Unfortunately, it was desecrated again during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. In the mid-1980s Khyungtrul’s chief disciple, Tenzin Wangdrak (bsTan-’dzin dbang-grags), restored the stone statue once more, so that it would be a fit object for religious devotion. It was then enshrined in a small temple at the place of discovery. The resulting product with its strange facial features and bright colors was somewhat garish, at least by Western tastes. Moreover, the thick layers of paint and clay had completely obscured the sculpture within. It was therefore quite a revelation when I saw photographs, a few weeks ago, of the statue stripped down to its stone core. Finally, one could appreciate its great artistic and historical value. It is not clear to me though whether it was originally a bust terminating in the pectoral region or if the statue once possessed a full body and appendages.

Fig. 5. A close-up of the head of the Khardong sculpture. Photo courtesy of Karma Gyaltsen.

Dranpa Namkha is one of the greatest personalities in Bon. He is attributed with mastering all higher teachings, composing various religious histories, and most importantly of all, with preserving the teachings by concealing texts during the persecution of Bon by the Tibetan king Trisong Deutsen (Khri-srong lde’u-btsan), in the 780s CE. He was thus given titles such as lachen (bla-chen; greatly superior one), khoepung (khod-spungs; fount of the teachings) and khyeu (khye’u; [purity like] youth). Of western Tibetan ancestry, Dranpa Namkha’s father, Gyungyar Mukhoe (rGyung-yar mu-khod), was the king of Khyunglung Ngulkhar, according to Bon texts.

We have no independent means at our disposal to determine if the Khardong sculpture is actually that of the great saint Dranpa Namkha (conventional Bon iconography depicts him quite differently). There are certain clues however that encourage us to see merit in this traditional attribution. Most important among them is the indigenous quality of the sculpture: it appears to have been produced in Upper Tibet. Although faint echoes of Sassanian and Gandharan art can be discerned on the face of the sculpture, it certainly belongs to neither cultural sphere. The esthetic connections to Tibetan Buddhist art and western Nepalese tribal art also appear tangential. Another important clue possibly confirming the identification with Dranpa Namkha is the non-Buddhist character of the sculpture. The wide triangular nose, large third eye set vertically in the forehead (a common feature in Hindu iconography), and prominent tiered topknot (thor-gtsug) all seem to point to an early bon iconography. A similar topknot is found in a red ochre pictograph of an archaic religious figure from the central Changthang (go to photo gallery – archaeology – photo captioned ‘a wrathful bonpo of Zhang Zhung’). As for the shape of the eyes, they are in a style that is typically Tibetan.

There are obvious iconographic correspondences between our statue and images of the Hindu god Shiva, such as the topknot and vertical third eye. Two of the greatest Tibetologists of the 20th century, Giuseppe Tucci and R. A. Stein, both considered it likely that Zhang Zhung culture in western Tibet was influenced by Saivism coming from Kashmir and other Himalayan regions. The existence of the Khardong stone sculpture appears to corroborate this historical scenario of religious traditions originating on the Indian Subcontinent permeating western Tibet, at least during the terminal period of Zhang Zhung (post-6th century CE).

As the Khardong statue was informed by parallel Indian and Tibetan Buddhist artistic traditions, its creation is likely to postdate the early 7th century CE. The highly unusual iconography and western Tibet provenance of the Khardong stone figure probably indicate the existence of a Zhang Zhung artistic tradition, the extent of which is still far from clear. While smaller non-Buddhist anthropomorphic figures of various kinds in metal have been recovered from the region, nothing so monumental has yet been reported in the scholarly record. The extreme rarity and historical significance of the stone image demand that it undergoes further inquiry. Hopefully, research will be stimulated by the introduction of the statue here to a wide audience.

I appeal to art historians and other specialists to share their knowledge and ideas about the Khardong sculpture. There is always room in this newsletter for the informed contributions of others.

Lucky but different: Non-standard auspicious symbols

Last month’s newsletter touched upon the ‘eight auspicious symbols’ (bkra-shis rtags-brgyad) of Tibetan religions. These have been an integral part of the artistic and ideological traditions of Buddhism and the analogous Bon religion for at least a millennium. In addition to these conventional demonstrations of good fortune and doctrinal insight, there were once other aggregations of lucky signs. These have come down to us in the rock art record and in metallic objects of the thokcha (thog-lcags) class of amulets, insignia and implements.

Fig. 6. Four auspicious symbols comprising a pair of fish, parasol, victory banner and endless knot, eastern Changthang. The grouping of these figures together and their current signification in Tibetan religions indicate that they are indeed symbolic in nature and not merely literal representations of objects.

Letters from a mani mantra were written over the pair of fish while another mani mantra and the syllable hum encroach upon the other three symbols. This superimposition of Buddhist inscriptions suggests that the symbols were made by non-Buddhists or those who might be loosely called bonpo. That these motifs have a non-Buddhist identity is supported by the fish symbol presented in last month’s newsletter, others among which are examined below.

Fig. 7. A close-up of the red ochre pair of fish in figure 6.

The manner in which the pair of fish was written over seems to show that they were neglected or had otherwise become obsolete or irrelevant. This pair of fish (nya), like others presented last month, has an unaffected quality, folk art that probably belonged to localized cults that existed before the definitive conversion of the region to Buddhism.

Fig. 8. The red ochre parasol (dbu-gdugs) in figure 6.

Although somewhat faded and worn, this pictographic parasol is clearly recognizable. This symbol may have signified the all-sheltering nature of the religious doctrine, as it does today.

Fig. 9. The red ochre victory banner (rgyal-mtshan) in figure 6.

Symbolizing the all-conquering nature of the religious doctrine (Bon or Buddhism), this particular victory banner was segmented into many horizontal bands; these may have been envisioned as having different colors, like Tibetan victory banners and standards today. The fourth symbol in the cave, the endless knot (pa-tra), is not singled out for illustration here.

Conspicuously missing from the same cave are the other four auspicious symbols of the standard grouping: vase (bum-pa), wheel (’khor-lo), conch (dung-dkar), and lotus (pad-ma). Why the set of symbols was abbreviated in this manner is not known. It may be that they were painted before the widespread introduction of the standard octad or as part of an alternative tradition. According to the religious history of the Taklung kagyu (sTag-lung bka’-rgyud) subsect, this corner of Upper Tibet did not fully convert to Buddhism until the early 13th century CE (for more details, see the book Divine Dyads, pp. 167–173). This date can be seen as the terminus ad quem for the creation of the symbols under consideration. The same cutoff date can probably be applied to most if not all ancient non-Buddhist rock art in the region. Given its rudimentary or archaic character, it is prudent to consider that the tetrad of symbols under scrutiny may have been painted as long ago as the early historic period (650–1000 CE).

If these symbols were indeed made during the early historic period, they coincide with the long transition from archaic forms of bon to the Lamaist religion still known today with its Buddhist-like doctrines and sensibilities. Very little of this transformation was candidly recorded in Tibetan texts, a collective amnesia serving to reinforce the new religious order. The transition from archaic to Lamaist Bon appears to have reached its final stage circa 980 CE. Red ochre inscriptions and art such as those featured in this newsletter appear to document this transformation in some detail, but study is impeded by a lack of reliable dates for their production. If and when rock art and epigraphy can be accurately dated, a powerful new tool will be added to our understanding of religious development in ancient Tibet.

Fig. 10. The eight-syllable mantra Om’ ma tri mu ye sa le ’du’ of the Bon religion and four auspicious symbols in a row, consisting of victory banner, five-pointed star, conch, and triple gems (this inscription and symbols were briefly discussed in last month’s newsletter). The pigment and wear characteristics of the inscription and symbols indicate that they were executed in the same general timeframe. The presence of the octosyllabic mantra, which does not occur in Old Tibetan texts, suggests that these ochre applications postdate 950 or 1000 CE.

The eight-syllable ma-tri mantra has been a mainstay of the Bon religion for upwards of a millennium. In practical terms, it is the counterpart of the Buddhist mani mantra, uttered universally by adherents. The ma-tri mantra inscription indicates a religious presence in the eastern Changthang either synonymous with today’s Bon or belonging to a formative regional tradition closely allied to it.

In addition to the four figures noted above, there are a number of other auspicious symbols on the same rock panel. In total, they can be tallied as follows: one victory banner, two vases, three endless knots, two five-pointed stars, one triple gems, one fish, one pair of fish, and one parasol. The triple gems and five-pointed star motifs are not part of the eight auspicious symbols. They appear to reflect a distinctly bon conception of what constitutes the ideal symbolic ensemble. Worth noting here is that in the Bon religion a star signifies an object made of meteoric metal.

Fig. 11. The unusually rendered parasol on the same rock panel as the Bon religious mantra discussed above. It was painted over a hunting scene consisting of an archer on horseback and a hound chasing two deer.

Fig. 12. The most graceful of the three endless knots on the same cave wall.

This highly worn and faded pictograph, like other auspicious symbols featured here, was most likely painted before the middle of the 13th century CE. The dharma wheel and lotus are not represented in non-Buddhist pictographs. Perhaps they were too closely identified with Buddhism to interest the followers of alternative religious traditions.

Fig. 13. A copper alloy fibula decorated with various auspicious symbols, circa 9th to 12th century CE. On the lower portion of the object are birds and what may be two pairs of fish, in addition to other symbols. Along the top section of the fibula is a row of nine auspicious symbols including (left to right) the pair of fish, conch, vase, endless knot and victory banner. Private collection, Lhasa.

Fibulae of this type appear to have been manufactured in western Tibet (they are consistently reported from this region) and broadly date from the 7th to 13th century CE. They are typically embossed with various kinds of propitious symbols, but like the pictographs examined above, these sets do not correspond with the standard eight auspicious symbols of Lamaism. It appears that during the artistic and conceptual development of the eight auspicious symbols a number of alternative sets or ‘systems’ existed, all of which eventually passed from favor. As these alternative assemblages are linked to non-Buddhist religious currents, they must have disappeared when Buddhism and its analogue, ‘Eternal’ Bon, came to dominate the religious-scape of Tibet. There may also be geographic factors in play with Upper Tibet having had its own repertory of felicitous emblems. In any case, these came to be replaced by the ubiquitous eight auspicious symbols of today.

Next month: more 2012 discoveries from Upper Tibet!