September 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung! The horned eagle flies swift and high, making more progress in the timely delivery of these monthly newsletters. The last issue featured a selection of remarkable anthropomorphic rock art and this month there is more to see, furnishing unique insights into the culture of ancient Upper Tibet. A second article examines parallels in the funerary rituals and mortuary customs of the Tibetans and the Xiongnu of Mongolia, illustrating how ancient traditions traveled far and wide in Inner Asia.

Horned, Feathered and Sanctified: Extraordinary anthropomorphs in the rock art of Upper Tibet – Part 2

Introduction

Outstanding anthropomorphic rock art in Upper Tibet reveals the cultural and religious activities of an ancient people in rich and intimate detail. Esthetically pleasing and deeply expressive, yet mysterious and entrancing, this rock art is of considerable importance to the broader study of Tibetan civilization. It provides unprecedented access to the beliefs, traditions and ambitions of a people who inhabited the highest land on earth.

Save for a few examples, the art featured in this and last month’s newsletter stands alone as complete rock art compositions. They are pictures of a special time and a special world, demonstrating that Upper Tibet had a strong tradition of rock art portraiture. Both animals and anthropomorphs are depicted in magnificent isolation, an artistic tradition that may have been more pronounced in Upper Tibet than in any other region of Inner Asia. Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic portraiture captures esthetic sensibilities, symbolic representations and religious proclivities as well as any other form of ancient art.

The archaeology, cultural history and ethnography of Upper Tibet are excellent tools for understanding the social, economic, political and cultural environment of ancient Upper Tibet. These disciplines can be applied to rock art to secure an impression or general understanding of the compulsions and mindset behind its creation. However, these fields of study cannot ferret out the specific meaning, disposition or selfness of individual compositions.

In this survey of extraordinary anthropomorphs certain cultural and thematic characteristics are repeated with much regularity, helping to define a distinctive genre of Upper Tibetan rock art. Among sacerdotal or divine figures, arms often reach towards the sky, as if their authority or power was celestially ordained. In tandem with this stretching of the arms upward, figures are frequently shown with legs spread apart in a stable pose, conveying mastery over the earth and the beings that reside on or below it. This physical attitude is reproduced in rock art from the Late Bronze Age (post-1200 BCE) until the early centuries of the second millennium CE. We know from the Tibetan literary and ethnographic records that ancient Tibetans divided their universe into two parts: sky and earth. These binary realms were the haunts of a variety of spirits. The sky realm was closely associated with male divinities such as the lha and the earth with the female srin-mo and klu-mo. Those divinities or wizards who controlled both spheres of existence exercised dominance over the dichotomous groupings of spirits. This mythological theme may help to account for the customary attitude of extended arms and legs in Upper Tibetan rock art portraiture.

A longstanding trait of extraordinary anthropomorph rock art in highland Tibet is the affixing of zoomorphic elements onto anthropomorphic depictions. The merging of avian and human qualities is particularly noteworthy and is discussed in last month’s newsletter. A standard physical attitude and the presence of zoomorphic motifs are cogent evidence not only for historical continuities in artistic style, but also for an enduring ideological fabric underlying its execution. Cultural legacies reaching back into prehistory even touch upon the modern period, as indicated by other facets of Upper Tibetan life I have documented over the last three decades.

Note: Dates assigned rock art below should be taken as suggestive and not prescriptive, as these dates are derived from proxy data and inference rather than direct chronometric testing.

Picture Gallery, Comments and Analysis

Fig. 23. A red ochre anthropomorphic figure holding a trident-like object. Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE) or Early Historic period (650–1000 CE), central Changthang.

We begin this month’s feature article with a pictograph of what appears to be a priest, shaman or deity. The three-pronged object carried in one hand may possibly be a trident. Tridents (kha-ṭam rtse-gsum) are used in Tibet by spirit-mediums (lha-pa), lay ritual practitioners (sngags-pa) and by some protective deities. The object depicted could of course have a different identity but in any case a ritual or symbolic function appears to be indicated. The anthropomorphic figure has long flowing hair and wears a full robe that may open down the middle. Its appearance seems to convey an attitude of protection or benediction, but any such interpretation is subjective.

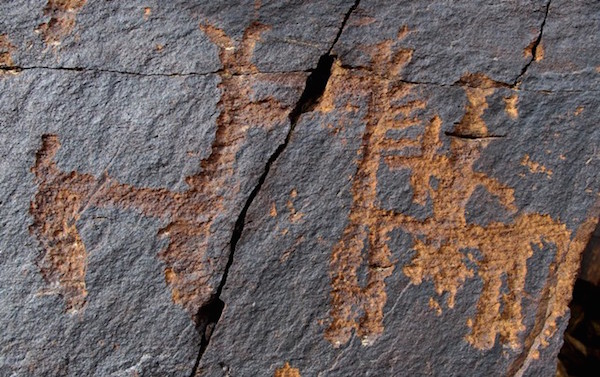

Fig. 24. A squatting figure, arms raised; its head ornamented with what appears to be feathers or rays. Photograph taken in the early 2000s. Protohistoric period, northwestern Tibet.

The pose of this anthropomorph may possibly signify an ecstatic state or that of birth giving. It cannot be ascertained whether a real human being, mythic figure or a deity is portrayed here. The petroglyph was engraved on a limestone surface, a relatively uncommon medium for the makers of Upper Tibetan rock art. At the time of photography, this composition was not in very good condition, precluding a more detailed analysis of its iconographic features. Circa 2008, this carving and many others at the same location were destroyed with explosives in order to build a dam. A closely related but more elaborately rendered figure is found less than 200 km to the west in Ladakh. Both of these petroglyphs are studied in an article I co-authored. See with Bruneau, “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS, 2013.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

While the rock art of Upper Tibet teems with hunters and their quarry, the composition pictured above appears to depict something different. In hunting scenes hunters are usually shown with bows and arrows and other weapons. However, in this portrayal there are no signs of a violent encounter. Therefore, a mystic or symbolic meaning may possibly be intended here. The anthropomorph seems to be carrying a drum or some other round object by its side. Its legs, arms and body are all flexed conveying a sense of movement. One or perhaps two of the accompanying animals appear to be carnivores. The middle zoomorphic subject resembles a wild sheep, and judging from its style, the technique used in carving and the more patinated condition of this animal, it was made at an earlier date than the surrounding figures.

The long tail attached to this figure is suggestive of bestiovestism, the transformation of humans into animals. This is a cultural theme with much currency in Upper Tibet. Today’s spirit-mediums, as well as ancient priests (gshen and bon), are thought to take on the form of animals for protective and healing purposes, and as a sign of their power and majesty. The rock art figure depicted here may have the snout or horns of an animal, while its bipedalism and gesturing arms are those of a human. The pose of this subject communicates a mystic or supernatural theme.

Fig. 27. A large anthropomorph with zoomorphic features situated next to a much smaller anthropomorph. Iron Age, northwestern Tibet.

This figure also has a tail, endowing it with zoomorphic qualities associated with bestiovestism. It brandishes a long object held upright. The other arm ends in a hand with three fingers or an object of three points. On the head of this anthropomorph, above two lines that may simulate hair or horns, there is a conspicuous three-pronged object attached to a long stem. Horns once again may be indicated for this unusual crowning motif. The broad torso, arresting accoutrements and tail of the anthropomorph may signify a deity. A supernatural identity is reinforced by the huge size of the figure in relation to the other one in the composition. The tiny figure seems to be portrayed in a more humanly conventional manner. It has one arm raised and may possibly be playing a drum as part of an invocation. The composition exudes a theophanic theme.

This unique figure seems to have the lower body of an animal and the upper body of a human. The form is one of great vitality and action. Arms spread, it appears to be carrying a long, upright object in one hand. Flaring of the head could possibly depict the brim of a hat or horns, among other things. While I do not know of centaurs being specifically mentioned in the mythology of Tibet, composite animal-human figures are a quite common leitmotif, particularly in the ancient context.

Here, too, this composition may possibly depict a human paired with a much larger deity. The bigger figure exhibits a rectangular head and very short rectangular arms. The arms point directly upward, as if signaling towards the realm of the gods or as part of another celestial theme. Short, rather non-descript legs, appear below the massive bi-triangular torso. An examination of the wear, re-patination and carving techniques employed reveal that the smaller anthropomorph was created at a considerably later date. This figure was cut right next to the bigger one in an act of tribute, worship or awe. Its tricuspidate crown is of the kind examined in last month’s Flight of the Khyung, one sometimes associated with raptors. Its legs and arms are spread in a demonstrative display. Male genitalia may possibly be depicted as well.

This willowy anthropomorph is no longer very clear, as the ochre pigment has undergone much wear. Attired in a long robe with a sash tied at the waist, the figure is depicted with an open neckline or a kind of jabot. The eyes are still visible but few other facial features. It is unclear whether the long object to the right of the figure is part of the composition. The identity of this anthropomorph is indiscernible: any number of ordinary or extraordinary attributions can be conjectured, but this does not at all detract from its beauty. This pictograph was first published in the November 2013 Flight of the Khyung.

Here we see another lone anthropomorph whose form is redolent with meaning. What allusions are connected to the bending of its legs, body and arms in a period before Buddhism arrived in Tibet is, however, beyond our knowledge. The well-proportioned athletic figure has an almost classical form.

This anthropomorph, arms raised and legs spread, is in the traditional birth-giving position. That this might be a female figure is reinforced by the large circle just above the legs, which is reminiscent of a womb. Something may be emerging from between the legs of the figure but the carving is ambiguous. Although prominent breasts are undepicted, this might not be uncharacteristic of a female portrayal. If this figure was perceived of as one of cosmic life-bestowing proportions, a schematized or abstract style might have been seen as most appropriate. Of course, the said circle could also depict the navel, giving the composition another but interrelated identity. The sun and swastika are life-generating symbols in Tibetan culture, as they are throughout Eurasia and further abroad. The lighter patination of the sun indicates that it was created at a later date than the other three subjects of the composition. The species of quadruped situated below the anthropomorph is undetermined.

The two anthropomorphs featured in this composition appear to possess zoomorphic traits. The figure on the right has a turtle-like body and head, and could be shown with a tail (or sword?). Its arms are holding or in contact with a large square. In the rock art of Upper Tibet, shields are most often square in form and this is one possible identity for the object. The figure on the left has outstretched wing-like arms, a long triangular body and what may be a prominent snout. Between it and the square wielding figure is a subject that superficially resembles a shrine (a commonly depicted subject in Upper Tibetan rock art). However, attached to this object is a long channel-like line terminating in a rectangle. Evidently, something momentous is being portrayed in this rock art, but save to say that it is ritualistic or mythological in nature, little more can be affirmed.

Fig. 34. An anthropomorph, line of bulbous objects and swastika-bird motif. Protohistoric period or Early Historic period, central Changthang.

This composition appears to show a priest, spirit-medium or deity carrying out a ritual, whether in a real life, historical or mythic context. The anthropomorph dons a crown or headdress of five prongs or tines, which once again brings to mind horns or feathers. The jutting face and headgear are animal-like in form. One arm is raised and pulled back while the other is gesturing towards a row of five round objects at ground level. The central object is larger than those flanking it and is surmounted by a three-branched motif. The line of five objects may portray offerings (mchod) or receptacles of deities (rten), mainstays of the Tibetan ritual tradition for many centuries. The swastika-like motif hovering over the anthropomorph could be a bird. Birds rendered in this way with either end of the two axes turned in the same direction (instead of opposite directions as with the standard swastika) are known from several sites in Upper Tibet. If this carving is really a bird, a theriomorphic identity is probably indicated, possibly as the patron or protector of the ritual. This petroglyphic composition was first published in Suolang Wangdui (Bsod-nams dbang-’dus), Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings. Introduction by Li Yongxian and Huo Wei. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House, 1994.

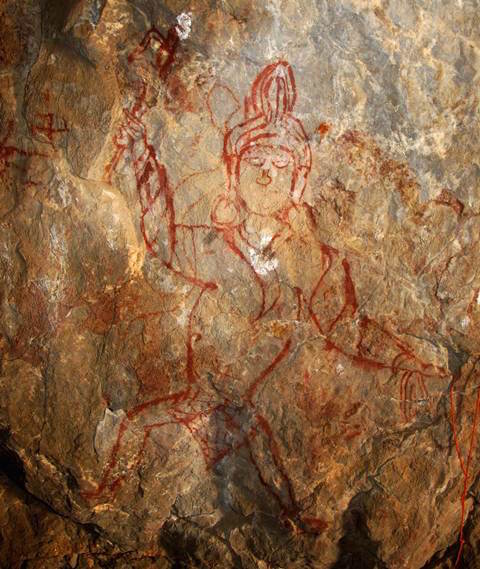

Fig. 35. This large red ochre pictograph of a turbaned anthropomorph is 2/3 life size. Early Historic period, central Changthang.

This impressive portrait of what is probably a priest or mystic belongs to a non-Buddhist religious tradition. Its makers are likely to have adhered to a regional, hierophantic or tribe-based cult, which along with others in Upper and Central Tibet, evolved to become the Eternal Bon religion in the the late 10th century CE. The value of this pictograph cannot be overestimated as it is one of the few to provide ample iconographic details. It was first discovered in the early 2000s by an art researcher from Tibet University (Lhasa). A turban winds around the figure’s head and very prominent topknot. Tibetan literary sources tell us that Tibetan priests and royalty alike wore turbans in ancient times. Large hoop earrings hang from the figure’s long ears. Semicircle eyes gaze over a small nose and mouth. The tight-fitting garment covering its torso opens down the middle of the chest. The sleeves fit tightly over the wrists. The patterned lower article of clothing ends in a pointed flap and resembles a tiger-skin loin cloth (characteristic dress of yogis). The thin legs of the anthropomorph appear to be bare. This priestly figure brandishes a hook in the right hand (a well-known Tibetan ritual implement), and has what may be a lasso or snare (another common ritual implement) coiled over its left hand. In the book Zhang Zhung (pp. 179, 180), I suggest that this anthropomorph is in the guise of a brahmin (bram-ze), as was Tonggyung Thuchen (sTong-rgyung mthu-chen), a famous 8th century CE Bonpo who spent a considerable amount of time around Lake Nam Tsho, in the eastern Changthang.

Fig. 36. This large red ochre anthropomorphic figure is found immediately to the left of the one in fig. 35. Early Historic period, central Changthang.

This important composition was also created as part of a non-Buddhist mystic or sacerdotal tradition, which appears to have existed during the Tibetan imperium as a counterpoint to the growing influence of Buddhism. The counterclockwise swastika painted above the left hand of the figure is shown in fig. 35. There are no indications of any clothing in the painting. The two-tiered pointed topknot is highly unusual, as are the eyes with vertical pupils and the two long fangs. Arms raised and legs spread, the pose of this figure is one commonly encountered in Upper Tibetan rock art portraits of extraordinary anthropomorphs from the Late Bronze Age onward. This kind of posturing communicates strength, confidence and status. Given its fangs and physical attitude, we might assume that this wrathful figure is depicted demonstrating religious or magical power and authority.

This priest, deity or magician presides over a tantric ritual in which a row of seven objects is used. Each of these pyramidal objects is topped by three pointed lines. The triangular shape of these objects recalls Tibetan offering cakes such as torma (gtor-ma) or dranggye (’brang-rgyas). They are directly comparable to the offering objects in the older rock art composition in fig. 34. The ritualist, legs spread, sports a crown consisting of three diadems. What may be an incomplete clockwise swastika or bird and a horse rider are found to the left of the main figure. The horseman appears to be an integral part of the composition, as does the hum’ syllable to the right of the main figure. The horse rider may possibly represent the benefactor of the ritual or could even be a depiction of the ritualist’s tutelary deity. Below the composition (not shown in photograph) is an engraving of the Vajra Guru mantra (for Guru Rinpoche). The inscription indicates that this ritual scene was created by Buddhist practitioners. The composition is part of the final phase of extraordinary anthropomorphic portraiture in Upper Tibetan rock art. Borrowing from longstanding cultural and artistic traditions, local Buddhists adapted the carving of exceptional anthropomorphs to their own purposes. In this case, the ritual portrayed may have been directed against local non-Buddhist practitioners, those more actively propagating symbolic and artistic forms that prevailed in Upper Tibetan rock art during the previous 2000 years.

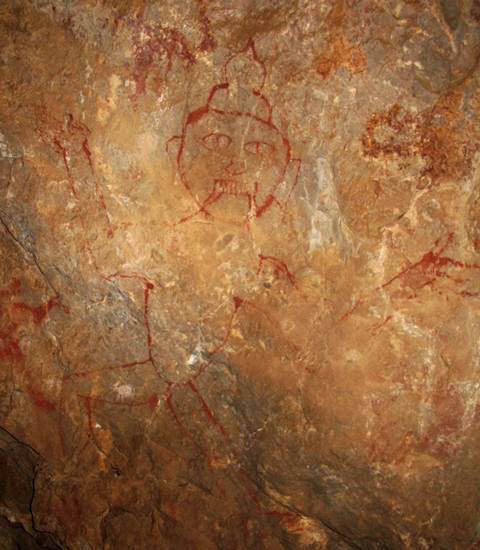

Fig. 38. A large pictograph of a non-Buddhist priest or god. Early Historic period or Vestigial period (1000–1300 CE), eastern Changthang.

This curious orange-red figure was painted on a beige background. Note the two counterclockwise figures just to the right of the background. The anthropomorph wears a pointed hat longitudinally divided into two parts. Pointed hats made of felt were worn in the eastern Changthang until modern times. Eyes, nose and mouth punctuate the round face of the figure. The counterclockwise swastika (exhibiting the same pigment type, application technique and wear as the anthropomorph) at the neck confirms the non-Buddhist identity of this figure. It was probably painted by members of a local religious cult, which can be generically referred to as bon, a precursor to the Eternal Bon religion. The short arms of the anthropomorph are raised, as they often are in this genre of rock art, whatever its age. A sash binds the long robe worn by the figure.

This head was rendered with a shallow carving technique associated with Early Historic period rock art in Upper Tibet. By only lightly cutting away at the rock surface, rock art compositions could be completed much more quickly. The face of the wearer has an almost cartoonish appearance. Characterized by perfunctory execution, naive realism and relative rarity, Early Historic period compositions represent a decadent stage in the development of Upper Tibetan rock art. The crown of five pointed diadems, each with a face, depicts the riknga (rigs-lnga), a crown still used by tantric practitioners today. This composition and others of the Early Historic period or Vestigial period underline the lasting influence of extraordinary anthropomorph portraiture in the Upper Tibetan rock art tradition.

The target of this standing archer is not clear because in the direction it is shooting there is another more elaborate composition that may be thematically unrelated (for this other composition, see figs. 13, 14, in the first part of this article). The archer in this composition wears a fan shaped headdress, which may possibly be made up of feathers. This figure appears to be attired in a shirt or short tunic and trousers. It cannot be ascertained whether a real life hunter or a mythic figure is being portrayed.

Fig. 41. Standing anthropomorph, legs and arms spread wide. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age, western Tibet.

This figure appears to be shown with exposed male genitalia, a fairly common form of depiction in prehistoric Upper Tibetan rock art. The identity of the composition remains unknowable: it could be a human being, mythic personality or deity. The unabashed nature of the portrayal of male reproductive organs bespeaks virility, courage, raw power, and other masculine qualities. For phallic representation in Upper Tibetan rock art, engraved agates and copper alloy talismans, see the Sept. 2010 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 42. A standing anthropomorph holding something aloft. Protohistoric period, northwestern Tibet.

The head and body of this unusually formed anthropomorph are composed of different sized squares. The short arms and legs of the figure are widely spread apart, and it seems to be holding up a banner or some other such object. It also appears to be represented with male reproductive organs. On the same boulder is a geometric motif and nondescript subjects, all of which seem to form an integrated composition with the anthropomorph.

Fig. 43. Another standing male figure with exposed genitalia. Protohistoric period, northwestern Tibet.

This boldly executed anthropomorph smacks of male vitality. On the same rock but at some distance away is a wild yak and stag carving that appear to have been made by the same hand.

Fig. 44. Two red ochre anthropomorphs, arms and legs spread. Protohistoric period, western Changthang.

These two figures stand as if watching over the small cave below. Although their pose is now familiar to us, it does little to establish the identity or function of these anthropomorphs. The subject on the right appears to display male genitals.

This is one of a multitude of hunting scenes in Upper Tibetan rock art. I have selected it for inclusion in this article because of the anthropomorph’s very tall headdress. Differences in the coloration of the carvings appear to be the result of highly localized geochemical processes.

This anthropomorph is clad in a long robe tied at the waist and a small, tight fitting cap. The hair, eyes, nose and mouth of the figure are all discernable. The sleeves of the robe are long, as they are in the modern chuba. The diagonally descending neckline of the robe seems to indicate that it closes on the left side of the body, an older style of Tibetan dress. Modern-day chubas and those of more recent periods generally close on the right side.

Fig. 47. A bowman taking aim at an animal (not pictured). Last part of the Protohistoric period or Early Historic period, northwestern Tibet.

This archer wears a long robe that closes along the left side of the body, an older form of dress in Tibet, as confirmed here. The figure is well executed, of realistic proportions, and stands pluckily with its bow and arrow.

A Review of Parallels in the Funerary Traditions of the Xiongnu and Tibetans

In 209 BCE, the chieftain Modun Chanyu united the tribes that formed the Xiongnu (Hsiung-nu) confederation, the most powerful political entity on the steppes for nearly two centuries. Improvements in military organization introduced by Modun during his 35-year reign include the apportionment of his army into quadripartite regional divisions known as the Four Horns. He also introduced an improved line of command and control in which leaders were assigned to each unit of ten, one hundred and one thousand men. These same military organizational structures were used by Tibetans during the imperial period (circa 650–850 CE). The tradition of four horns and decimalized military units must have colored the martial lore and traditions of regions peripheral to the Xiongnu Empire such as Qinghai, Gansu and Xinjiang, before filtering down to northern or western Tibet and finally onto the Central Tibetans by the early imperial period.

The influence of Xiongnu military organization on Tibetans eight centuries after the founding of the steppe empire appears to be yet another example of north Inner Asian cultures playing a formative role in ancient Tibet. Similarly, plate (laminar) armor pioneered by the Xiongnu (as well as by the Scythians, Sakas, Sassanids and Parthians) also made its way in due course to the heartland of Tibet. According to Bon tradition, this type of armor was used in Zhang Zhung.

This article touches upon interpretations for Xiongnu mortuary culture based on parallel funerary customs and traditions of the Central and Upper Tibetans.* These customs and traditions do not appear to have arisen from direct contacts between the two peoples. This is borne out by the contrasting sets of burial monuments and grave goods in each region. The rock art and other aspects of material culture of the Tibetans and Xiongnu are also largely unrelated to one another. This is not surprising, in that there are large distances between the Xiongnu empire and core regions of the Tibetan plateau. Rather, parallels between the funerary culture of the Xiongnu and Central and Upper Tibetan are best explained as being derived from a common cultural progenitor(s).

For Tibetan archaeological and literary materials, see the books Zhang Zhung and Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet. For the Xiongnu archaeological materials, I rely here on the most comprehensive work of its kind, Treasures of the Xiongnu (ed. G. Eregzen), Institute of Archaeology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 2011.The movement of Bronze Age peoples such as Tocharians and Andronovs eastward may possibly account for the cognate mortuary customs and funerary beliefs described below. On geographic and chronological grounds, the Tocharians and Andronovs seem the best candidates for sowing traditions with a lasting impact on both the steppes and Tibetan plateau. It may be these culturally complex groups that helped spread chariot and mascoid rock art and attendant ideologies throughout Inner Asia in the Bronze Age. Thus the Xiongnu archaeological evidence and Tibetan literary evidence presented here are probably best seen as having originated through older transcultural prototypes. Seminal aspects of funerary culture may have been transmitted to the Xiongnu via the Scythians and Slab Grave culture, among other intermediaries, while imperial period Tibetans may have picked them up from the early Turks and Zhang Zhung. Archaeological evidence I have uncovered indicates that Zhang Zhung is likely to have had communications with the Scythians, either directly or through intervening Iron Age cultures native to Xinjiang.

In elite Xiongnu burials, the head of corpses face northward (Treasures of the Xiongnu, p. 45). Using Tibetan cultural parallels as a basis for comparison, this appears to signify the direction of the afterlife. In Old Tibetan literature, the afterlife or ‘Joyous Land’ (dGa’-yul) is described as the “northern parts” (byang-rnams).

According to Treasures of the Xiongnu (p. 45), broken Chinese bronze mirror fragments often found in elite tombs of the Xiongnu were deposited, “…in order to release the essential spirit of the object, thereby rendering it useful in the world after death”. Using Tibetan archaic funerary culture as a point of comparison, I have formulated a contending hypothesis. As the otherworld closely parallels the one of the living, unbroken objects would likewise have been seen as most useful. Accordingly, Tibetan literature suggests that gifts for the next world were deposited in tombs in good condition. As for the broken Chinese mirrors, I believe these were used to enshrine the soul or spirit of the dead during evocation rites. Once the essential persona of the dead was sent heavenward the mirror was broken to prevent any hindrance to the journey. Similarly, Tibetan receptacles for the soul of the deceased (bla-rten) were dismantled or broken to prevent reoccupation by the deceased. Treasures of the Xiongnu (p. 143) alludes to this theme when describing the separation of the body and spirit in shamanic rituals. The deliberate breaking of bronze vessels and plates (pp. 166, 173) may reflect a cognate eschatological theme. The occurrence of broken Chinese mirrors in Xiongnu graves suggests that this foreign object was utilitarian in function and dispensable in nature, as befits a commodity from a rival nation.

The skulls and bones of horses and sheep deposited in elite Xiongnu tombs (pp. 45, 47, 195) are likely to represent one or more categories of funerary ritual activity. These include appeasement sacrifices for demons interfering with the passage of the deceased to the afterlife, as provisions for the next world, and as animal guides and / or carriers that ritually transported the dead to the afterlife. A guiding function is suggested by the placement of a horse and sheep skull on an earthen shelf above the head of the corpse (p. 57). Another excellent indication of the existence of the psychopomp horse in Xiongnu burials is the deposition of bits, cheekpieces, breast collars, bridle decorations and other parts of horse harnesses in Xiongnu tombs (pp. 194–217).

Fig. 1. A Xiongnu burial, Burkhan tolgoi, Bulgan, Khutag-Undar, Mongolia. Note the horse skull, sheep skull and long bones of animals at the head of the burial. Presumably, these animals were sacrificed in order that they could accompany the dead to the afterlife. Photo courtesy of Treasures of the Xiongnu.

The lids of some timber coffins of the Xiongnu are painted with spiraling cloud motifs and flying birds (pp. 62, 65). I see these motifs as replicating the overhead pathway to a celestial afterlife, one not unlike that described in Tibetan archaic funerary literature.

In Treasures of the Xiongnu, it is speculated that orifices of corpses were sometimes sealed with pieces of jade to protect the spirit (p. 143). Quite to the contrary, I see this custom as being carried out to prevent reanimation of the corpse by the deceased, which would prevent him or her from reaching the otherworld. In Tibet the cutting of the corpse still serves the same purpose.

Treasures of the Xiongnu tells us that cup-like oil lamps made of ceramics, bronze and iron are found near the head of corpses (pp. 188, 189). This appears to be the material correlate to the well-developed Tibetan eschatological theme of a lamp or symbolic lamp (such as a precious stone, horns or a thread-cross) illuminating the way through the murky postmortem existence en route to the heavenly afterlife.

Among harness and breast collar decorations found in Xiongnu tombs are those with animal motifs including the yak, deer, mountain goat, unicorn of antelope-like appearance, and dragon (pp. 205, 208–213). Again, using the Tibetan archaic funerary tradition as a model, the animals depicted on these objects must have functioned as protectors and guides of the dead.

Fig. 2. Decorative silver plates of a breast collar depicting an ibex-like unicorn, from burials at Gol Mod, Khairkhan, Arkhangai province, Mongolia. The hooked horn of the unicorn may have functioned to catch the soul of the deceased, so that it could be transported to the afterlife. In the Tibetan archaic funerary tradition, horns have powerful apotropaic functions. The stylized clouds around the unicorns suggest that these psychopomps were envisioned as celestial creatures. Photo courtesy of Treasures of the Xiongnu.

Next Month: Sinuous Shapes: How Tibetans adopted the Eurasian ‘animal style’!