November 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung! This month’s issue features a general interest article on the origins of Tibetan art, as seen through ancient rock carvings and paintings. It explores the relationship between rock art and the classical art of Tibetan Buddhism that first appeared in the 7th century CE.

This article was first published in 2013 on the Himalayan Art Resources website (http://www.himalayanart.org), under the behest of Donald Rubin, a longtime benefactor of my research work. It appears under the following URL: http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=3108. However, the formatting of the work was not completed and it was never added to the general site index, despite my repeated communications with the director of Himalayan Art Resources. I have therefore taken it upon myself to republish the article here in Flight of the Khyung, permitting more people to read it and enjoy the images in the proper sequence. Please note that this work has been specially edited for the newsletter.

Before the Mural and Scroll Painting: Rock Art in Ancient Tibet

Introduction to the rock art and classical art of Tibet

A perusal of its monasteries, temples, palaces and other sources demonstrates that Tibet produced a huge array of religious paintings and sculptures over a long span of time. Buddhist murals and statuary can be traced back to the 7th and 8th centuries CE, while the oldest painted scrolls or thangkas date to the 10th or 11th century CE. As in many other parts of the world, the classical religious art of Tibet was preceded by more ancient traditions of figuration painted and carved on stone. This rock art is of two major types: petroglyphs (engravings on stone) and pictographs (paintings on stone).

Tibetan Buddhist art owes its esthetic inspiration to India, particularly to the regions of Kashmir and Bengal under the Karkota and Pala dynasties respectively. The Licchavi kingdom of Nepal also had a formative impact on Tibetan painting and sculpture. Sogdiana and Khotan in Central Asia were major influences on the development of classical religious art in Tibet as well. The introduction of Buddhism and other foreign cultural inputs on the Tibetan Plateau beginning in the 7th century CE led to a major reordering of its civilization. As a result, the indigenous religions of the Plateau known generically as bon waned. This archaic bon is not to be confused with the (Yungdrung) Bon religion, the Lamaist counterpart to Tibetan Buddhism, which arose in the late 10th century CE.

The older artistic traditions of Tibet possessed their own cultural makeup, physical environment, social compulsions, and economic priorities. Conversely, Buddhism and Bon are part of a more recent world, one in which foreign cultural and religious patterns played a huge role. As rock art is a very different kind of medium from classical forms of art, it is hard to single out the historical connections between them. Rather than a specific subject or genre of prehistoric art acting as direct inspiration for the creation of classical art, antecedent pictorial traditions exerted a more diffuse esthetic and cultural influence, shaping the styles and motifs of classical art in an uncritical or unremarked fashion.

Although rock art is the historic forerunner of Tibetan Buddhist and Bon painting, the functional links between them are muted. Indigenous religious traditions such the cult of territorial deities, utilitarian ritual practices and life-cycle celebrations did indeed infiltrate Buddhism and Bon, including its figurative arts, but these were reconfigured to embody the ethical guidelines, philosophical principles and esthetic sensibilities of the two classical religions. In the realm of art antecedent customs and traditions are most recognizable in costumery, ornamentation, armaments, zoomorphic imagery, and symbology. Pre-Buddhist motifs, however, tend to serve as a subtext to the main doctrines and practices expressed in Buddhist and Bon art.

There are also other major differences between the archaic and classical art worlds of Tibet. Rock art was a more inclusive enterprise in which both those with and without specialized artistic skills could participate. This medium is generally more rudimentary in execution and composition, reflecting the inherent challenges of painting and cutting uneven stone surfaces while being exposed to harsh weather conditions. The elementary character of rock art also seems to betoken a less diverse economic regime than the one prevailing in more recent times.

The motivations for creating rock art remain hypothetical, contrasting with the well-articulated religious purposes for which Buddhist and Bon art was and is made. We can infer from the preponderance of hunting scenes, as well as battles and martial contests, that Tibetan rock art encompassed more pedestrian or pragmatic concerns. Mythic and ritualistic scenes are represented in rock art as well, but pinpointing the cultural expressions intended by the makers is not possible in any objective sense. We are left, therefore, with broad indications of what the abstract significance and practical usage of archaic art might have been to its makers and original viewers.

Technical considerations: Age and location

To better appreciate how archaic artistic traditions contributed to the pictorialization of Tibetan Buddhism and Bon, we shall examine petroglyphs and pictographs that both predate and are contemporaneous with these religions. The rock art presented in this study is all located in the uppermost portion of the Tibetan Plateau, in the regions situated north of the Transhimalayan ranges and west of Lhasa (Changthang), the upper Brahmaputra valley (Martshang Tsangpo), and far western Tibet (Tö). This vast territory of some 300,000 square miles can be referred to as ‘Upper Tibet’.

A note on dating rock art is in order. The attributions provided below should be viewed as suggestive and not prescriptive. At this time scientifically verifiable methods for gauging the age of rock art worldwide are still under development. A number of inferential methods for formulating a chronology of rock art are currently used by specialists. These include stylistic analysis, identification of content, appraisal of physical characteristics, examination of the relative position of paintings and carvings, collateral archaeological evidence, cross-cultural comparison, and interpretation of literary and ethnographic sources. It must be stressed that none of these methods are completely reliable and are best used to devise a relative chronology, which determines what compositions might be older or newer than other ones. The chronology employed in this study is as follows:

Prehistoric epoch

- Late Bronze Age (circa 1500–800 BCE)

- Iron Age (ca. 800–100 BCE)

- Protohistoric period (ca. 100 BCE to 600 CE)

Historic epoch

- Early Historic period (ca. 600–1000 CE)

- Vestigial period (ca. 1000–1300 CE)

Gallery of rock art images

Fig. 1: On this flat-topped boulder there are more than 25 animals, most of which appear to be wild herbivores indigenous to Upper Tibet (wild yaks and sheep). In the middle of the boulder is a lightly re-patinated animal of more recent production. Iron Age.

While Tibetan mural and thangka paintings are generally more complex than rock art, boulders, cliffs and caves containing upwards of 100 interrelated petroglyphs and pictographs are known. Frequently, hunters either on horseback or on foot are depicted among intricate animal compositions. The function of the rock art bestiary in fig. 1 is a matter of speculation. More favored hypotheses include an articulation of social or ceremonial obligations, ritual magic for hunting, and expressions of thanksgiving.

Fig. 2: This complex composition with its counterclockwise swastikas, crescent moon, sun, trees, bird-of-prey, yak, other wild herbivores, anthropomorphic figure with bow or some other object, and unidentified motifs appears to embody a mythic, ritual and/or narrative theme. Protohistoric period.

The medley of subjects depicted in this painting were of seminal importance to the hunting way of life in Upper Tibet, and include animals used for food and the natural constructs that sustained them. The swastika, sun and moon are still key cosmological and religious symbols in Tibet and often grace classical religious art. However, it is not prudent to attempt to transfer their historic meanings in toto to the prehistoric cultural setting. While longstanding cultural continuities exist in Tibet much has also changed over time, obscuring historical links.

Fig. 3: Swastika painted in red ochre. Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

The counterclockwise swastika is the symbol of the Bon religion par excellence, but its origins as a rock art motif go back to prehistory. On the other hand, Tibetan Buddhists use the clockwise swastika, setting them apart from the Bonpo in an easily recognizable way. The powerfully painted swastika depicted here was painted in red ochre (oxides of iron), the most common pigment used in Tibetan rock art. According to David and Janice Jackson (see bibliography), red ochre (tsak) was also utilized by painters of early thangkas.

Fig. 4: Eccentric swastika. Iron Age.

It was in the Early Historic period that the direction of the swastika became a marker of sectarian affiliation. In prehistoric rock art, swastikas are oriented in both directions with no apparent differences in their mytho-ritual context. Like the whimsical example shown here, some early swastikas have arms turned to align with the opposite side. Some of these non-standard swastikas resemble birds. Birds and swastikas were well-known solar symbols in Eurasia, possibly accounting for the hybrid design in Tibet.

Fig. 5: Sun, moon and swastika. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age.

In addition to the swastika, the sun and moon figure prominently in the symbolic rock art of Upper Tibet. In Buddhist and Bon art the sun often cradles a crescent moon, signifying the union of the methods and wisdom that lead to enlightenment. In more ancient rock art the sun and moon usually appear separately on stone surfaces. In this composition, the two were carved in conjunction with a swastika. The sun with its spokes and hub resembles a chariot wheel, a motif that may also have had solar symbolism in the rock art of Upper Tibet. At the same rock art site with the triad of symbols illustrated above there are numerous petroglyphs of chariots with similar wheels, providing us with an indication of its antiquity. In the historic epoch, Tibetans did not regularly use wheeled vehicles for transport.

Fig. 6: This complex red ochre composition features a conjoined sun and moon, two sunbursts, tree, counterclockwise swastika, and many dots. Protohistoric period or Early Historic period.

Gracefully executed, the concentration of all these crucial symbols seems to signify a cosmological or cosmogonic theme. Trees and a variety of other vegetation as well as the sun and moon are often used to enliven thangka paintings, but these are subsidiary features rather than central motifs.

Fig. 7: A horned eagle (khyung) hovering above a wild herbivore. Protohistoric period.

Due to the horns on the bird, we can presume that this raptor was conceived of as a supernatural creature. Thus, the maker of this boldly rendered composition may well have intended it to have ritual or mythological import. The khyung is still a popular subject in thangka paintings, adorning the tops of thrones and as a primary figure in its own right. In Tibetan Buddhism and Bon, the khyung is a tantric symbol and deity, protector god, and attribute of the esoteric mind training school known as Dzokchen. Bon texts further tell us that the khyung was once an important clan deity in Upper Tibet. Given the textual indications that have come down to us, the khyung may also have functioned as an ancestral and protective spirit in prehistory. It is not clear what is being conveyed by the pairing of a horned eagle with what appears to be a wild yak (drong). One possibility is that they are symbols of the dichotomous universe, the sky and earth. Nevertheless, other interpretations are also admissible.

Fig. 8: Horned eagle with outstretched wings. Iron Age.

This majestic khyung is found among a menagerie of animal carvings. According to Bon historical texts, the khyung was a royal and priestly emblem of the Zhang Zhung kingdom in Upper Tibet. Some Bon literature suggests that the so-called bird horns were crest feathers on certain species of avifauna. These ‘horns’ are said to possess demon-destroying properties.

Fig. 9: A group of four or five birds with outstretched wings. Bronze Age or Iron Age.

These birds appear to be dancing in the sky. Carved in isolation, it is not clear whether this composition was merely a literal representation of flying raptors or one charged with the cognitive and emotive imprints of complex cultural traditions. Flying birds frequently soar through the air in thangka paintings but as subsidiary figures.

Fig: 10. A beautifully rendered bird with a crest of three points, eyelike body ornamentation and tripartite tail. Iron Age.

This petroglyph seems to portray the silhouette of an eagle or other bird-of-prey. In murals and thangkas birds are shown standing, flying and swimming as ancillary background figures. However, in ancient rock art animals play a much more central role and were often depicted in isolation. Some of these depictions may be zoomorphic deities but it is very difficult to distinguish the numinous from more prosaic renditions of animals.

Fig. 11: A red ochre duck or goose pictograph. Early Historic period.

Like much historic epoch rock art, this bird is realistically painted with many easily recognizable anatomical details; however, the execution is somewhat stiff. The wing of the water fowl forms a narrow arc across the striped body and its tail feathers spread out like the fingers of a hand. The painting is somewhat obscured by other pigment applications. Ducks and geese fill the ponds and lakes of many murals and thangkas, part of the idyllic environments in which deities reside.

Fig. 12: Confronted carnivores prancing or fighting among a variety of other animals (not shown). Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

The figure on the left has a long muzzle, pointed ear, and what appears to be a long tail curled over the graceful body. These are common motifs in the feline (tiger) rock art of Upper Tibet. The animal on the right with its big head and chest and curved tail with a ball at the end is lion-like. These creatures may have served a variety of functions for the artist (clan symbols, military emblems, zoomorphic spirits, objects of trance states, etc.), none of which we can know for certain. In thangkas protective deities (srungma) are commonly accompanied by wolves, bears, felines, raptors, and other fierce animals, which serve as their minions and agents of power.

Fig. 13: With its gaping jaws, pointed ears, long curling tail and stripes this appears to be the likeness of a tiger. Protohistoric period.

There is a prehistoric genre of striped carnivore art in the region suggesting that at one time the tiger may have been native to Upper Tibet. Scenes of these big cats attacking wild yaks and other wild herbivores of the region reinforces this impression. In thangka art there are a variety of protective and tutelary deities that ride tigers. However, in Upper Tibetan prehistoric rock art, there are no gods or goddesses portrayed riding tigers or other carnivores.

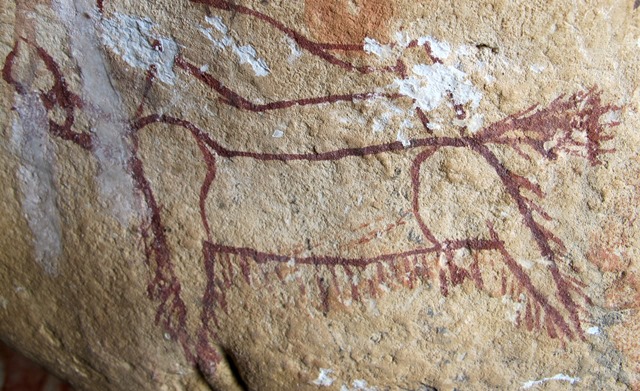

Fig. 14: A red ochre stag identified through its branched antlers. Iron Age.

The most popular figurative subject in the rock art of the Tibetan highlands is the wild herbivore. Next to wild yaks, deer are the most common species represented. According to Tibetan literature, deer fulfilled several ancient ritual functions, serving as sacrificial offerings, psychopomps and the mounts of deities. While these kinds of religious purposes may possibly also be indicated for rock art deer, this remains unconfirmed. The earliest Tibetan literature dates to circa 700 CE and its description of more ancient times cannot necessarily be taken literally.

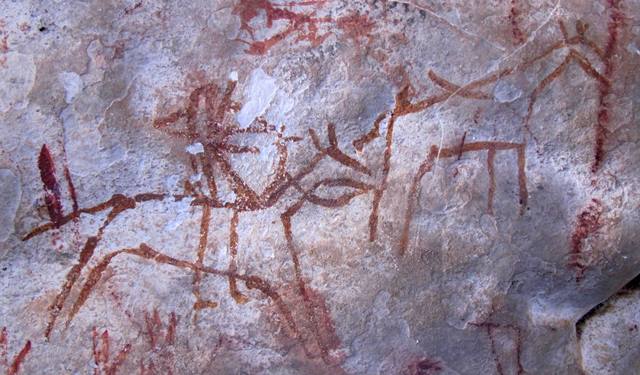

Fig. 15: Two gamboling antelopes with spiraling horns. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The two antelopes in this composition were rendered in a style of art closely aligned to the steppes and the various Scythic tribes known as Sakas. This genre of art is only found in northwestern Tibet, evidently a conduit for cultural interactions between the Plateau and the deserts and steppes to the north. As with most ancient rock art styles, there are no exact counterparts in the murals, thangkas and statuary of Buddhism and Bon.

Fig. 16: A wild herbivore with curled horns most resembling an argali. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The argali (nyen) is the largest species of sheep in the world. Since the carving of this animal the rock on which it was made has deeply split. The simplicity yet vibrancy of the figure is a hallmark of prehistoric rock art in Upper Tibet. While animals in Buddhist and Bon art can also be highly stylized and dramatic, they lack the raw potency of earlier art.

Fig. 17: A wild yak carved in magnificent isolation. Iron Age.

This wild yak was made in a style characteristic of Upper Tibet, marked by circular horns, ball-like tail, belly fringe, and large rounded withers. Like the two herbivores in fig. 15, the body of this animal is ornamented with the scroll motif characteristic of the Upper Tibetan version of the Eurasian animal style. The rock cracked (through weathering) after the petroglyph was made, an indication of considerable antiquity. This yak may have had either prosaic or preternatural connotations for its maker. Be that as it may, in Tibetan Buddhism and Bon, yaks are the vehicles of territorial deities (yulha) and the personal protective spirits of men, women and warriors.

Fig. 18: A wild yak with what appears to be an anthropomorphic rider. Iron Age or Protohistoric period.

The significance of this intriguing composition is debatable. It is not very likely that bull yaks (gender indicated by the long belly fringe) were customarily ridden in Tibet. This understanding leads us to consider that the composition may depict a deity or some other kind of supernal figure. If so, this demonstrates that the tradition of Tibetan deities riding yaks is of prehistoric origins, just as Bon ritual texts maintain.

Fig. 19: A wild bull yak boldly painted in an ochre with a magenta hue. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age.

This adroitly painted animal and others like it in the same cave belong to the oldest stratum of pictographs in Upper Tibet. They could be as old as the late second millennium BCE. This genre of painting is associated with a rich color palette ranging from mustard and orange to the deepest reds. No such style of painting exists in Buddhist or Bon art, which is many centuries more recent.

Fig. 20: An archer mounted on a horse taking aim at a wild yak. The yak has already been hit in the back by three projectiles. Iron Age.

Quarry in Upper Tibetan hunting scenes is often depicted mortally wounded in this manner. It seems to signal that this depiction was used either as a charm to attract game, a forum for showcasing hunting skills, or as a celebratory gesture after the successful completion of a hunt. These kinds of graphic killing scenes of ordinary animals do not occur in Buddhist and Bon art, as these religions are based on an ethic of nonviolence. Hunting compositions, as much as any other class of prehistoric figuration, highlight the stark cultural differences between archaic and classical art.

Fig. 21: A hunter on horseback shooting an arrow at an animal resembling a Tibetan wild ass (kyang). Iron Age.

Although the hunter is merely a stick figure, there is much vitality in his form. The reins of the horse and dangling legs of the hunter are prominent motifs in this composition. As in Figure 20, the prey has already been struck by an arrow. An orange-red ochre was used to create this composition.

Fig. 22: A mounted hunter with a bow and what appears to be a pike painted with a black pigment. Protohistoric period or Early historic period.

The hunter seems to be shooting an arrow as he closes in on the two large wild herbivores (wild yaks?). This finely rendered pictograph has suffered much wear. The use of black pigment is much less common than red ochre in the pictographs of Upper Tibet. Carbon from soot and ash are regularly used in thangka painting to make black pigments, but the chemical composition of this pictograph remains to be determined. In addition to charcoal, manganese dioxide has been used as a rock art pigment since the Stone Age in sundry parts of the world.

Fig. 23: A horseman shooting a bow. Protohistoric period.

This erect figure is part of a hunting scene (the rest of it is not illustrated). The hunter appears to be sitting on top of a tall saddle (with pummel and cantle depicted), a type still used in Tibet today. However, there is no clear sign of stirrups in the composition. Metal stirrups were not widely adopted in Inner Asia until after the advent of the Turks in the 5th century CE. The wedge-shaped object on the rear of the horse may represent the horsemen’s gear. The double curved profile of the bow identifies it as the so-called Scythian or recurved type.

Fig. 24: Figure on horse brandishing a bow with what may be a quiver on his back. Protohistoric period.

This horseman with a topknot is not part of a hunting scene. The depiction of battles, martial contests and ceremonial functions in which equestrians participate are part of the Upper Tibetan rock art tableau. The bow and arrow is also carried by a wide spectrum of wrathful and protective deities in Buddhism and Bon. From the hunting weapon of choice in ancient times, it has come to symbolize the piercing of ignorance in the modern religions of Tibet.

Fig. 25: Anthropomorphic figure standing before a row of circular objects with a swastika-like bird overhead. Protohistoric period.

Anthropomorphic figures in what appear to be mythological and ritual portrayals also adorn Upper Tibetan rock surfaces. It cannot be determined conclusively however if these figures represent deities, ancestral luminaries, priests, spirit-mediums or mythic heroes. In any case, all these possible identities are represented in Tibetan literature and in the oral tradition. In the scene depicted in fig. 25 an anthropomorphic figure gestures towards a row of five round objects, the middle one of which is surmounted by a plant-like object (these may possibly be offering cakes). On the head of the ostensible ritualist is a crown or headdress with five protuberances resembling diadems (known in classical art). Above the anthropomorph a swastika-like bird watches over the proceedings.

Religious and mythic themes connected to rich narratives lie at the heart of Buddhist and Bon art. This art is inspirational and pedagogic in nature, part of a living tradition that can be studied and understood in both a traditional and academic sense. No such claims of intellectual understanding can be made for ancient rock art. It belongs to a cultural sphere that has mostly vanished. Even when traditions and concepts documented in the Tibetan literary and ethnographic records are applicable, rock art remains too uncomplicated and ambiguous in appearance to confirm what these might constitute in each individual example.

Fig. 26: A bent anthropomorphic figure assuming a pose that appears to be ritualistic in character. In addition to a long tail, this figure may have two horns on its head. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age.

As this evocative figure was carved in isolation there are no other subjects that might lend it a clearer context. According to Bon texts, the prehistoric kings of Zhang Zhung wore crowns of bird horns. These texts also refer to horned deities especially those that underpin old funerary traditions. Moreover, Bon speaks of the transformation of ancient saints into animals in the course religious rituals such as the retrieval of lost souls. It is not known however if any of this textual lore is relevant to the composition in fig. 26. All that can be safely stated is that it appears to depict an extraordinary activity or event, one in which sacerdotal or supernatural personalities may be incumbent.

Fig. 27: An anthropomorphic figure seemingly dancing with a large bird. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age.

On the same rock face (not illustrated) is an animal and unidentified curvilinear motifs that may be part of the same composition as the bird and anthropomorph. This exceptional composition appears to encapsulate a mythic or religious theme. The bird with its outstretched wings and large triangular tail is typical of ornithic depictions in Upper Tibet. The placement of the right arm of the anthropomorph mimics the aspect of the bird (the position of the left arm is more ambiguous). This identification with birds could possibly indicate a shamanistic activity, as in an ecstatic flight to the heavens.

Fig. 28: Two unusual anthropomorphic figures. The figure on the right can be attributed to the Late Bronze Age or Iron Age and the one on the left to the Protohistoric period.

The figure on the left stands with spread arms and legs. On the top of its head are three prominent lines, which may possibly simulate rays or feathers, both of which are attested in Bon accounts of prehistoric Upper Tibet. This anthropomorph is of a type seen at other rock art sites in Upper Tibet (it is reminiscent of the specimen in Figure 25). The figure on the right has an hourglass-shaped body and stubby arms raised up towards its square head. The abbreviated appendages and tiny head may suggest that it limns a supernatural being. The two figures were carved using different techniques and exhibit varying degrees of re-patination, indicating that they were made in different periods. The retroactive coupling of these figures suggests that they were conceptually integrated into a single supramundane theme.

Fig. 29: An anthropomorphic head crudely carved in shallow relief. Early Historic period or Vestigial period.

The technique employed to engrave this rock art is characteristic of the historic epoch. The crown of five diadems (rignga) is a recognizable historic religious trait. It is still used by Buddhist and Bon tantric practitioners and spirit-mediums. This type of headdress is also worn by various deities including the popular class of female divinities known as ‘sky-goers’ (khandro). Thus, we cannot know if the carver of this petroglyph intended it to represent a human or divine figure. In this example of the rignga, simple eyes, mouth and nose were engraved in each diadem. These may represent the five directional Buddhas (Gyalwa Rignga), a class of divinities found in paintings, statuary and on the diadems of headdresses.

Fig. 30: A five-tiered shrine with bulbous top. Protohistoric period.

Upper Tibetan rock art is replete with the facsimiles of shrines consisting of graduated steps. These include rudimentary examples like this one as well as more complex and later forms known as stupas (Sanskrit) or chortens (Tibetan). In addition to architectural and religious influences coming from the Indian Subcontinent, Tibetan chortens owe their origins to more basic shrines of prehistory. Elementary shrines are still common in contemporary Tibet. Bon ritual texts contain accounts of them, and they were used to enshrine deities for effecting various practical objectives. According to Bon tradition, the graduated layers of these monuments symbolized the five elements (ether, air, water, earth, and fire). The ruins of early tiered shrines have been discovered at various locations in Upper Tibet. Miniature models of these structures in copper alloys and stone have also been documented. Likewise, copper alloy, iron, wooden, ivory and stone Buddhist and Bon chortens in various sizes and styles are well known. Chortens figure prominently in religious paintings as well.

Fig. 31: A polychrome chorten or a precursory variant of shrine. Early Historic period.

The precise architectural status of the structure depicted in this carving is unclear. The minor figures to the right of the shrine have not been identified. Polychrome pictographs are uncommon in Upper Tibet. This example was painted using red ochre, yellow ochre (ngangpa) and a white pigment. According to David and Janice Jackson (see bibliography), yellow ochre was rarely used as a pigment by thangka painters, but was exploited as the primary undercoat for gold in Tibetan paintings. The white pigment of the pictographic shrine is most likely calcareous in composition such as the mineral chalk or gypsum.

Fig. 32: From left to right: a dagger (phurba), ritual thunderbolt (dorje) and bell (drilbu). Vestigial period.

This nicely executed pictograph was made by an individual thoroughly acquainted with Buddhist religious objects. The dagger, ritual thunderbolt and bell are widely represented in Tibetan classical art. In the first few centuries after the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet, its chief symbols and implements formed a substantial theme in rock art. Flanking the trio of ritual tools are two clockwise swastikas (one in yellow and one in red), another essential sign of Tibetan Buddhism. The exact reasons the artist chose to paint these motifs cannot be known to us. Perhaps he was a meditator or magician who occupied the cave. Alternatively, they may have been drawn by a peripatetic lama conferring his blessings on the locale in this way. It is also conceivable that these potent symbols were laid down to religiously secure the location and expel non-Buddhist or bon practitioners. The cave contains several counterclockwise swastikas possibly suggesting a clash or encounter between Buddhists and non-Buddhists. The bright yellow pigment used to produce the pictographs might be orpiment (arsenic trisulphide), a pigment regularly used in thangka paintings.

Selected Bibliography

BELLEZZA John V. 1997. Divine Dyads: Ancient Civilization in Tibet. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

____2000. “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet”, Rock Art Research [Melbourne] 17 (1), pp. 35–55.

____2000. “Images of Lost Civilization: The Ancient Rock Art of Upper Tibet”, in Asian Art Online Journal, http://www.asianart.com/articles/rockart/index.html

____2001. Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau. Delhi: Adroit Publishers.

____2002. Antiquities of Upper Tibet: An Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Sites on the High Plateau. Delhi: Adroit Publishers.

____2002. “Gods, Hunting and Society: Animals in the Ancient Cave Paintings of Celestial Lake in Northern Tibet”, in East and West [Rome] 52 (1–4), pp. 347–396.

____2004. “Metal and Stone Vestiges: Religion, Magic and Protection in the Art of Ancient Tibet”, in Asian Art Online Journal, http://www.asianart.com/articles/vestiges/index.html

___2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts, and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Forthcoming. BRUNEAU, Laurianne and BELLEZZA John V. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’”, in Revue d’etudes tibétaines [Paris].

CHAYET Anne. 1994. Art et archéologie du Tibet, Manuels d’archéologie d’Extrême-Orient, Civilisations de l’Himalaya. Paris: Picard.

CHEN ZHAO FU. 1988. Découverte de l’art préhistorique en Chine. Paris : A. Michel.

___1996. “Rock Art Studies in the Far East During the Past Five Years”, in P. G. BAHN and A. FOSSATI (eds.), Rock Art Studies: News of the World I. Recent Developments in Rock Art Research (Acts of Symposium 14D at the NEWS 95 World Rock Art Congress, Turin and Pinerolo, Italy, pp. 127–131. Oxford: Oxbow Books (Oxbow Monograph 72).

___2006a. Zhongguo yan hua quan ji – Xibu yanhua (1) (The Complete Works of Chinese Rock Art – Western Rock Art Volume 1), vol. 2, Beijing: Liaoning meishu chubanshe.

___2006b. Zhongguo yan hua quan ji – Xibu yanhua (2) [The Complete Works of Chinese Rock Art – Western Rock Art Volume 2], vol. 3, Beijing: Liaoning meishu chubanshe .

FRANCFORT Henri-Paul. 1992. “Archaic Petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar”, in M. LORBLANCHET (ed.), Rock Art in the Old World: papers presented in Symposium A of the AURA Congress, Darwin (Australia), 1988, pp. 147–192. New Delhi: IGNCA.

JACKSON David and Janice. 1988. Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials, illustrated by Robert Beer. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications.

JIANG ZHEMING. 1991. The Rock Art of China. Beijing: New World Press.

LI YONGXIAN. 2004. “The Discoveries of Rock Painting in Zhada Basin and Some Ideas on Tibetan Rock Painting”, in Huo Wei / Yongxian Li (eds.), Xizang kao gu yu yi shu guo ji xue shu tao lun hui lun wen ji (Essays on the International Conference on Tibetan Art and Archaeology), pp. 30–46. Chengdu: Sichuan renmin chubanshe.

SUOLANG WANGDUI (Bsod-nams dbang’-dus). 1994. Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House.

TANG HUISHENG. 1989. “A study of petroglyphs in Qinghai Province, China”, in Rock Art Research [Melbourne] 6 (1), pp. 3–10.

TANG HUISHENG and GAO ZHIWEI, 2004. “Dating analysis of rock art in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau”, in Rock Art Research [Melbourne] 21 (2), pp. 161–172.

TANG HUISHENG and ZHANG WENHUA. 2001. Qinghai Yanhua. Beijing: Science Press.

WU JUNKUI and ZHANG JIANLIN. 1987. “Xizang Ritu xian gudai yanhua diaocha jianbao (A brief investigation report on ancient rock art of Ritu, Tibet)”, in Wenwu [Beijing] 2, pp. 44–50.

ZHANG JIANLIN. 1987. “Ritu yanhua de chubu yanjiu [Initial studies of rock art in Ritu, Tibet]”, in Wenwu [Beijing] 2, pp. 51–54.

Next Month: A new survey of a Final Bronze Age necropolis in Upper Tibet!