February 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another soaring Flight of the Khyung! The destination of this month’s exaltation is the Tibet Museum in Lhasa and its prehistoric collection of artifacts. Images of a representative sample of Neolithic stone implements, ornaments and other objects from the Tibetan Museum are highlighted here. The featured photographs and accompanying descriptions will be of interest to admirers of Tibet’s ancient cultural heritage and of value to archaeologists and cultural historians.

The second article in this newsletter reviews a recently published article on the origins of agriculture in Tibet by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. It also looks at other questions related to the introduction of agriculture in Western Tibet.

The Prehistoric collection of the Tibet Museum in Lhasa – Part One

Introduction to the Tibetan Museum

The Tibet Museum is Tibet’s premier repository for antiquities, spanning the prehistoric and historical epochs. Its prehistoric collection represents the most important assembly of Tibetan Neolithic stone implements and ceramic vessels in the world. A smaller but still important collection of Iron Age and Protohistoric period ceramics and metal objects are also held by the institution. The Tibet Museum’s historic collection boasts a fine array of ancient Buddhist art, political symbols of power and ethnographic objects.

The umbrella organization managing the Tibet Museum, the Tibet Autonomous Region Cultural Relics Bureau is a key institution for the study of Tibetan antiquities and cultural history. The TAR Cultural Relics Bureau is actively involved in archaeological research and conservation projects throughout the TAR.

The Tibet Museum first opened its doors in 1999. The museum reopened to the public with expanded collections on display after refurbishment in 2014. The prehistoric collection on view is now far more extensive than before renovations took place.

The Tibet Museum is located on Norbu Lingka Road, opposite the main entrance to the Norbu Lingka religious estate. It is reported that the museum contains 10,451 m² of floor space for exhibition. For more general information about the Tibet Museum, here are a few links:

For a description of the Tibet Museum and its holdings, see the website China Tibet Information Center:

http://zt.tibet.cn/english/zt/culture/20040200451384554.htm

Much of the same information as above is found on Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tibet_Museum_%28Lhasa%29

For a short article about the prehistoric collection of the Tibet Museum entitled “Tibet’s Prehistory Culture in Tibet”, see the vTibet website:

http://www.vtibet.com/en/news_1746/ctbnews/201407/t20140728_216102.html

A selection of Buddhist paintings and sculptures held by the Tibet Museum can be viewed on the website Himalayan Art Resources:

http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setid=1380&page=1

Dozens of pictures of mostly Buddhist-era exhibits from the Tibet Museum have been posted online by the photo archivist Brian McMorrow:

http://www.pbase.com/bmcmorrow/lhasamuseum&page=1

A short video featuring some of the Tibet Museum’s exhibits (mostly Buddhist era) is on YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7SjgV69vHM

Clare E. Harris has written an incisive account about colonialist and modern political machinations associated with the acquisition of antiquities in Tibet, and the role museums play in supporting an agenda that extends beyond scientific study and conservation: The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Introduction to Stone Age artifacts in Tibet

Only basic information (in Tibetan, Chinese and English) about artifacts is recorded in the Tibet Museum displays: type of object, location and age. Detailed site, period or excavation data are hardly included in the exhibitions. Further analyses and descriptions of each class of objects, as well as an in-depth treatment of each major period and region in Tibetan prehistory, would be very useful to visitors, helping to make better sense of what they are seeing.

This article (Part One and Part Two) makes a modest contribution to fulfilling the goal of providing more information about the holdings of the Tibet Museum, but much more work is needed if its invaluable collections are be curated to an international standard of excellence.

All photographs included in this survey of the prehistoric collection of the Tibet Museum were taken by the author. Cameras are freely permitted inside the exhibition halls and I used this privilege to document nearly all of the Neolithic, Metal Age and Protohistoric objects on public display.

All descriptions, including types of objects, locations and dates provided in this article, are based on labels accompanying each object or group of objects. If I think necessary, these data are modified in the captions and supplemented with additional descriptive information. Below some photographs, I also append my own comments.

This article will not focus on stone artifacts attributed to the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age in the Tibet Museum collection). Paleolithic studies are not my area of expertise. For those interested in this formative period of human development on the Tibetan plateau, the best overview studies in English remain:

Chayet, A. 1994. Art et Archéologie du Tibet. Paris: Picard.

Aldenderfer, M. and Zhang Yinong. 2004. “The Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau to the Seventh Century A.D.: Perspectives and Research from China and the West Since 1950” in Journal of World Prehistory, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–55. Springer: Netherlands.

The above two works include extensive bibliographies of more specialized studies of the Paleolithic and subsequent prehistoric periods in the development of Tibet. Please note that there remains a good deal of disagreement among specialists about which stone tools found in the TAR actually date to the Paleolithic. Even most artifacts generally agreed upon as belonging to Paleolithic typologies in the TAR have come from the surface and lack a secure archaeological context. The dating of these objects is still undergoing formulation.

As one can see, exploration of this remote period in Tibetan human development is still limited to just a handful of sites. Many other such sites await scientific inquiry.

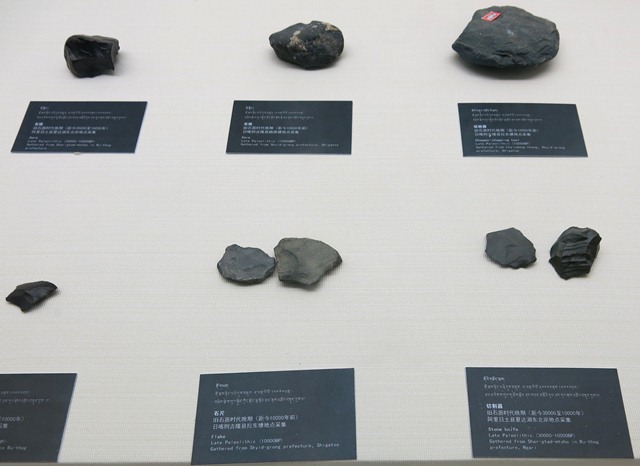

Fig. 2. Hand-axe discovered at Shartay Tsho (Shar-gtad mtsho), Ruthok. Upper Paleolithic (30,000–10000 Before Present). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 3. Stone cores, scrapper and choppers from Shartay Tsho and Kyirong (Skyid-grong), Upper Paleolithic (30,000–10,000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

The Neolithic is also a poorly understood chapter of prehistory on the Tibetan plateau. In addition to Chayet 1994 and Aldenderfer and Zhang 2004, a fine general study of the Tibetan Neolithic is:

Aldenderfer, M. 2007. “Modeling the Neolithic on the Tibetan Plateau” in Late Quaternary Climate Change and Human Adaptation in Arid China, Developments in Quaternary Sciences, vol. 9, (eds. D. B. Madsen, F. H. Chen and X. Gao), pp. 149–161: Elsevier.

For a review of Aldenderfer 2007 and other articles germane to the peopling of the Tibetan plateau, see the May 2013 Flight of the Khyung.

As will become evident as one goes through the photos below, the two most important Neolithic sites excavated to date in the TAR are Kharub (Kha-rub) in Chamdo and Chugong (Chu-gong) in Lhasa.

Kharub is sometimes referred to as Kharo (Mkhar-ro). It is situated on a bench above the Dzachu (Rdza-chu; Mekong river) at 3100 m above sea level. It was excavated to a relatively high standard in the late 1970s, led by the Chinese archaeologist Tong Enzheng, and again by a different team in 2002. Kharub, an agricultural settlement, in its various phases of occupation has been dated to circa 4000–2100 BCE. These dates are based on the radiocarbon analysis of organic samples collected on site and on a typological study of ceramics. Nonetheless, further inquiry is needed if chronological discrepancies that remain in the archaeological record of Kharub are to be ironed out.

In addition to hunting and foraging, millet was cultivated at Kharub and pigs and cattle appear to have been reared there. In the lower strata of the Kharub settlement, microliths were found in association with ceramics. A wide range of floral and faunal remains were collected at Kharub, but the archaeological study of these materials has proven rather rudimentary. For more information on Kharub’s subsistence economy, see the second article in this newsletter.

As one will see in this survey of the Tibet Museum’s prehistoric collection, a large variety of objects were discovered at Kharub including stone tools, metates, bone awls and needles, ceramic vessels, stone jewelry, and stone spindle whorls (indicative of a weaving tradition), among other items. In fact, the greatest variety of Neolithic ceramics and stone tools in the TAR was discovered in Kharub. Around one dozen other Neolithic sites have been documented near the Dzachu river, in the vicinity of Kharub.

Chugong, on the northern edge of Lhasa valley, is situated at 3680 m above sea level. It has been dated to circa 1800–1100 BCE. Only a few minor architectural features (ash pits, tombs) were detected at Chugong. The ceramics recovered from this site exhibit more advanced production techniques (finer fabrics, higher firing temperatures, wheel-turned construction) than those from Kharub. Microliths, bone tools and grinding implements were recovered from the highly disturbed site. A single copper alloy arrowhead was also discovered at Chugong, indicating a familiarity with Bronze Age technology (either as part of local production or importation). Both hunting and animal husbandry were practiced (reportedly, yaks, sheep and pigs were raised at Chugong). The relationship between tombs discovered at the site and dated Neolithic remains is still obscure.

Another site in Central Tibet with cultural affinities to Chugong is Tranggo (’Phrang-sgo), located near the bank of the Brahmaputra (Yar-lung gtsang-po) river in Gongkar (Gong-dkar county). See the second article below for more details about this site.

From the findings made at Kharub and Chugong, Chinese and Tibetan archaeologists reason that these and other Neolithic sites like them are the cultural and demic precursors to later periods in the evolution of Tibet. While this is very plausible, archaeological data documenting the transition from the Tibetan Neolithic to the Tibetan Metal Age (Chacolithic and Bronze Age, if they existed as discrete technological and cultural phases) is still woefully lacking. The relationship between earlier sites unearthed in Eastern and Central Tibet and Iron Age civilization is also obscure.

Although I (and others) have surveyed a wide range of Iron Age rock art and monumental remains in Upper Tibet (includes Western Tibet and the Changthang), the only Neolithic sites studied in that vast region are located in Ruthok. This work by Chinese archaeologists, however, is preliminary in scope. Therefore, it is still not evident how precisely Neolithic sites contributed to subsequent cultural and demographic developments in Upper Tibet.

A Photographic Gallery of Neolithic Implements and Ornaments in the Tibet Museum Collection

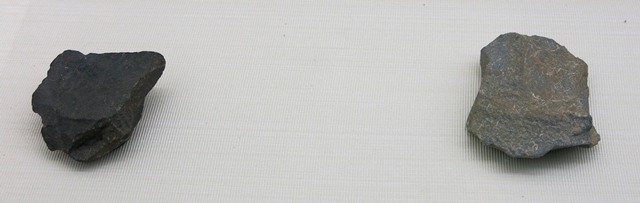

Fig. 4. Stone chisels, Metok (Me-tog) prefecture (southeastern Tibet). Late Neolithic. Tibet Museum collection.

These two objects do not appear to be chisels but rather a specialized tool that was perhaps used in basketry or tanning. Presumably, “Late Neolithic” here denotes a period between 4000–3000 BP. The dating of Neolithic type sites in the temperate and subtropical forests of the Me-tog region, however, requires further investigation.

This polished axe-head or celt actually appears to be made of gem-grade serpentine. As in other parts of the world, Tibetan polished axe-heads made of high-quality stones may have had ceremonial or ritual functions, and could have been traded over a wide area as prestige goods.

Fig. 6. Polished jade chisels, Kharub (Kha-rub), Chamdo. Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

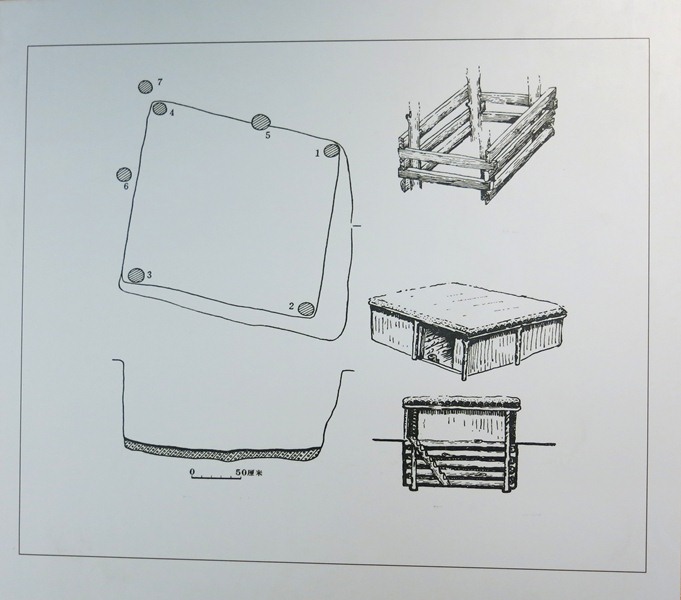

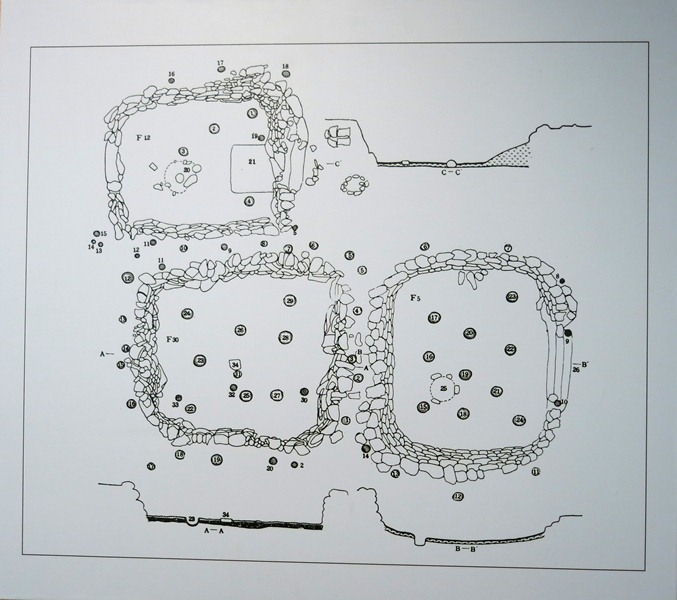

Fig. 7. A ground-plan (upper left), stratigraphic diagram (lower left) and artist’s reconstruction of the exterior and interior walls of one of three such dwellings from the early phase of occupation at Kharub (fourth millennium BCE). Tibet Museum collection. These semi-subterranean dwellings were each between 14 m² and 24 m²

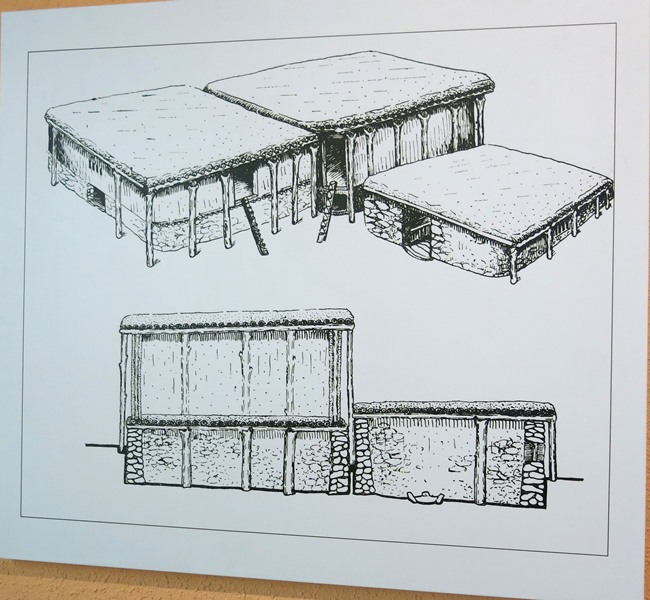

Fig. 8. Artist’s reconstruction of a dwelling from the late phase of occupation at Kharub (third millennium BCE). Tibet Museum collection.

As noted in Chinese archaeological reports, the design of such dwellings anticipated major architectural features of historic-era domiciliary construction in Tibet, such as the flat roof, windowless walls and two-story construction.

Fig. 9. Ground plan and cross-section view of excavated dwelling at Kharub from the late phase of occupation (third millennium BCE). The various smaller circles designate postholes. The larger circles with intermittent lines represent hearths. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 10. Polished white jade axe-head, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

This object may have functioned as an adze rather than an axe.

Fig. 11. Polished stone axe-head, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 12. Polished stone axe-head, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 13. A stone axe-head with spatulate form, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 14. Polished stone chisels from Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 15. Microlithic blades and cores, Drongpa (’Brong-pa), Upper Tibet. Dated to 7000–5000 BP. Tibet Museum collection.

Note that the chronology given by the Tibet Museum for microlith technology is not secure. Chronometric evidence from other sites, suggests that certain types of microliths were made as recently as 2900 years ago.

Fig. 16. Wedge-shaped micro-cores, Drongpa, Upper Tibet. Dated to 7000–5000 BP. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 18. Microlithic cores (conical, polyhedral, wedge-shaped), Chugong (Chu-gong), Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 19. Conical, polyhedral and wedge-shaped cores, Chakrithang (Lcags-ri thang), Damshung county. End of the Neolithic (Eneolithc?) (3200–2900 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

A large variety of microlithic objects were found at Chakrithang. These are discussed and illustrated in Cultural Relics Bureau of Tibet, Shaanxi Archaeological Research Institute, and Department of Archaeology of Sichuan University, 2005: mTsho bod lcags lam khongs bod ljongs khul gyi gna’ rdzas rtog zhib kyi snyan zhu, Beijing: Kexue chu banshe.

Fig. 20. Scrappers, Chakrithang, Damshung county. End of the Neolithic (3200–2900 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 21. Microlithic flakes, Ngamring (Ngam-ring), Upper Tibet. Dated to 7000–5000 BP. Tibet Museum collection.

As noted above, the designated dates for these stone tools are not secure.

Fig. 22. Stone tools of uncertain function. Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 23. Ovoid stone blades, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 24. Jade frows, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Identified by the unifacial cutting edge, frows were primarily used as a cleaving tool. Like an adze, the handle was set at right angles to the stone head.

Fig. 25. Perforated, semi-crescent-shaped stone sickle blade, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Similar stone sickles are found in the Neolithic cultures of the upper Yellow River valley.

Fig. 26. Perforated stone sickle blade, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 27. Polished stone (serpentine?) adze, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of the Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 28. Rectangular stone bladelets, Kharub, Chamdo. Late Phase of the Neolithic (circa 4000 BP). The white blade on the left is perforated. Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 29. Stone tool with serrated edge, Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

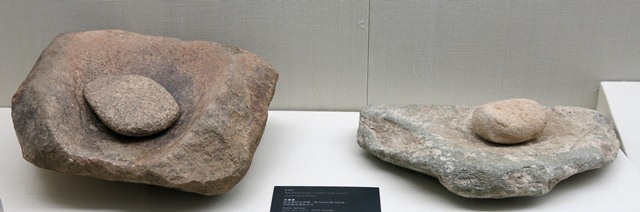

Fig. 30. Bottom row: stone pestles, Chugong, Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Middle row (right): stone spade and stone hoe, Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP). Middle row (left): stone spade, Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP). Upper row: various stone tools, Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP); and Chugong, Lhasa, Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 32. Sheep or deer astragalus, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

As in later times, this knucklebone may possibly have been used as a gaming piece or ritual object.

Fig. 33. Tusk of musk deer, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

This tusk and the one of a boar bucktooth next to it (not pictured) may have functioned as a tool or possibly as an ornament.

Fig. 35. Bone needles, some with eyes for threading, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

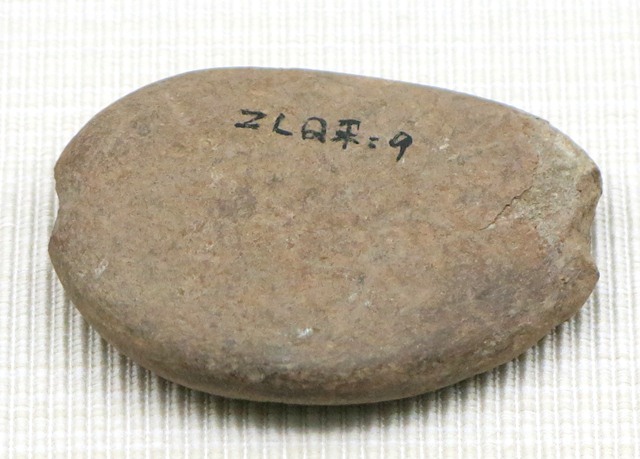

Fig. 36. Stone spindle whorl, Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 37. Stone sinker on net (?),Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 38. Bone awls, Chugong, Lhasa, Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP); Kharub, Chamdo, Middle or Late Phase (5300–4000 BP); Kharub, Late Phase (4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 39. Stone balls with hole in middle of unknown function, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 41. Two fragments of what might be stone bracelets (the larger of which is scored with a geometric pattern), Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 42. Two bone plates (right) and bone bar (left) of varying functions, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 43. Bone hairpin, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 44. Stone pendant of malachite, a cylindrical bead of turquoise (?) and beads of other substances, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

These beads anticipate later lapidary designs in Tibet. The finds from Kharub show that already in the Neolithic Tibetans enjoyed beads made from a variety of substances. Some of the beads illustrated may have been trade items.

Fig. 45. Small tabular stone objects, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

Fig. 46. Ceramic discs and perforated triangular object of unknown function, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

The ceramic disc on the left appears to have thirteen punctated eyes. This kind of design and numerical arrangement is also found in Tibetan copper alloy discs and mirrors, which were produced some 1500–4000 years later.

Fig. 47. Shell ornament, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

A hole was drilled through both ends of this cowrie-like shell, marking it as an ornament or ritual object. It is also possible that this shell was used as a medium of exchange. In Tibet, cowries remain important cultural objects to this day, with both ritual and ornamental functions. The shell from Kharub probably came from the Indian Ocean or possibly from the South Pacific. Its presence in Kharub demonstrates that extensive trade networks extending from the Tibetan plateau to the seacoast existed in the Neolithic. Cowries are found at Neolithic sites of Mongolia, the ultimate source of which was the Indian Ocean. For a cultural study of cowries in Tibet, see the May 2014 Flight of the Khyung.

The broad-based system of trade and exchange that appears to have encompassed Eastern Tibet in the Neolithic is likely to have functioned as a vehicle for the transmission of manifold cultural outputs. Details of Tibet’s role in intercultural material, symbolic and intellectual transactions during the Neolithic, however, are still lacking.

However the situation is changing for the better. Progress in understanding interactions between Neolithic cultures on the northeastern Tibetan plateau and on the loess plains and hills of northwestern China has been made thanks to a recent article by Ling-yu Hung, Jianfeng Cui and Honghai Chen: “Emergence of Neolithic Communities on the Northeastern Tibetan Plateau: Evidence from the Zongri Cultural Sites”, in The ‘Crescent-Shaped Cultural-Communication Belt’: Tong Enzheng’s Model in Retrospect. An examination of methodological, theoretical and material concerns of long-distance interactions in East Asia (ed. Anke Hein), BAR International Series 2679: Oxford, 2104.

The above article postulates a more refined model for the Neolithicization of northeastern Tibet, with multilateral cultural and technological exchanges playing a large role. Its authors help to revise an earlier assumption that large-scale demic diffusion from northwestern China were chiefly responsible for the appearance of the Tibetan Neolithic. I will be revisiting the Ling-yu Hung et al. paper at a later date.

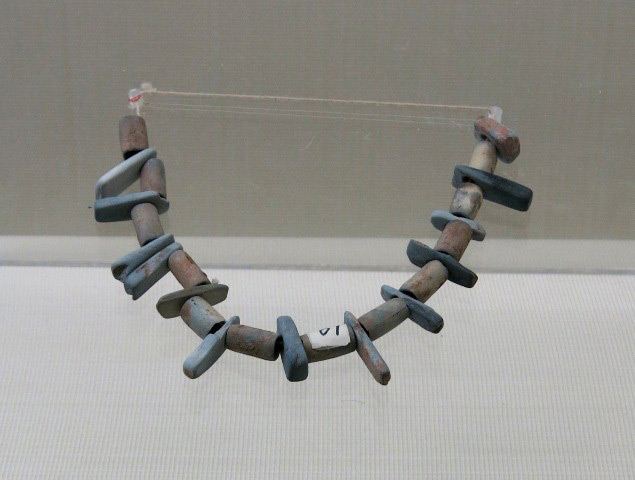

Fig. 48. A stone (jasper?) necklace, Kharub, Chamdo. Middle or Late Phase of Neolithic (5300–4000 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

With alternating red cylindrical beads and blue tabular ones, this necklace indicates that the inhabitants of Kharub either produced or traded for sophisticated forms of jewelry. Neolithic necklaces with alternating cylindrical or round beads and tabular ones are known from various places in Eurasia as far afield as Britain.

Fig. 50. A ceramic monkey-like head, Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

The facial features were incised and pressed into the unfired clay.

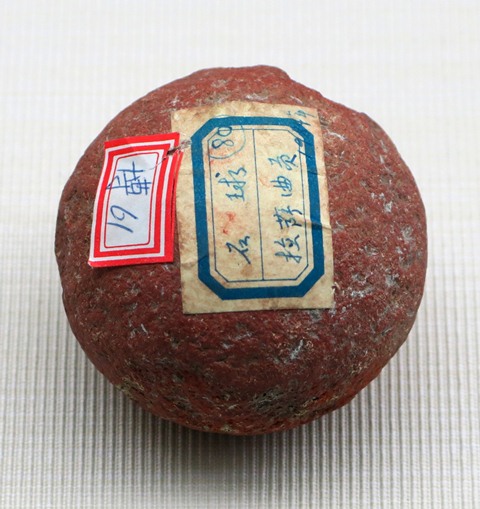

Fig. 51. A stone ball tinted with red ochre, function unknown, Chugong, Lhasa. Late Neolithic (4000–3500 BP). Tibet Museum collection.

A number of red ochre-tinted stones, as well as grinding stones for preparing this pigment, were discovered at Chugong. Red ochre has a long legacy of usage in Tibet. Red and yellow ochre paint was used in Tibetan rock art, the earliest of which dates to the first millennium BCE. Red ochre was also applied as face paint in the Imperial period (650–850 CE). Red ochre is still employed medicinally and as a pigment in Tibet today.

Early Agriculture in Tibet: A Review of a recent scientific paper by d’Alpoim Guedes et al.

Here I briefly review a scientific article published in 2014 by the authors Jade d’Alpoim Guedes, Hongliang Lu, Yongxian Li, Robert N. Spengler, Xiaohong Wu, and Mark S. Aldenderfer entitled “Moving agriculture onto the Tibetan plateau: The archaeobotanical evidence”, in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, vol. 6, pp. 255–269. After describing the salient elements of this article, I will offer a few of my own comments.

This article by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. is a very welcome addition to the archaeobotanical study of early agriculture in Tibet. It synthesizes data from previous studies to furnish the reader with an up-to-date overview of the debut of agriculture on the Tibetan plateau. This work reviews how agriculture seems to have spread in Tibet, and how food crops may have been adapted to cope with the harsh environmental conditions of the Plateau.

In addition to reviewing archaeobotanical data from other studies, this article presents the findings of the authors from two far-flung sites on the Tibetan plateau: Kharub* in the east (with calibrated dates of circa 2700–2300 BCE) and Khardong in the west (with calibrated dates of 220–334 CE and 694–880 CE). From the available archaeobotanical and archaeozoological evidence, the authors conclude that the first stage of agriculture in Tibet entailed millet (broomcorn and foxtail) farming and the rearing of swine, a pattern of economic subsistence that is likely to have originated in northwestern China. Another agropastoral system in Tibet was based on the cultivation of wheat, barley, peas and millet, and on sheep and goat pastoralism, as the authors note.

The authors call this site by its Sinicized name: “Karuo”.Using a macrobotanical analysis of economic plant remains found at Kharub and Khyunglung, the authors argue that early farmers on the Tibetan plateau experimented with various crops to devise the best strategies for coping with difficult high altitude conditions. The authors maintain that the first crops grown in Kharub were foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum), which appear to have been introduced from the highlands of western Sichuan or from the northeastern fringe of the Tibetan plateau (in Gansu and Qinghai), circa 3500 BCE.

The authors of the study state that another suite of crops introduced into Tibet by circa 1400 BCE includes bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), naked or hulless barley (Hordeum vulgare var. nudum) and peas (Pisum sativum). As is well known, these crops were cultivated in Southwest Asia (8000–11,000 years ago) before spreading eastward.

Recent genetic evidence summarized by the authors indicates that the naked barley and six-row barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grown in Tibet have a monophyletic origin, pointing to Southwest Asia as the ultimate source for their domestication. The authors observe that, as in northern Europe, before wheat and barley could be grown in Tibet, phenotypes that permitted sowing in Spring had to be developed. The authors do consider that gene flow between indigenous wild barley and the introduced domesticates possibly occurred, creating local barley cultivars that were especially well adapted to the environmental conditions of the Tibetan plateau.

The authors review the epic spread of western plant domesticates (wheat, barley, peas) across Central Asia, noting that by 2800–2300 BCE they had reached Neolithic sites in Kashmir. Western plant domesticates may have reached China in the third millennium BCE, but the evidence is still tentative. Certainly, in the second millennium BCE wheat and barley was being grown in the central plains of China.

According to d’Alpoim Guedes et al., evidence for a wide range of western domesticates first appears in Central Tibet at Tranggo (’Phrang-sgo), in the Yarlung Tsangpo valley (Gongkar county).* It appears that in the late second millennium BCE or early first millennium BCE, a free-threshing variety of wheat, naked barley, pea, rye (Secale sp.), and naked oat (Avena nuda) were known in Tranggo, either as trade items or cultivated crops. The authors caution though that this list of domesticated plant species is somewhat tenuous due to the sample collection methods used by Chinese archaeologists involved in the study of the site.

The authors use transliterations of Sinicized Tibetan names: “Changguogou” and “Gongga”.The authors cite a study by Wagner et al. 2011, which indicates that evidence relating to pastoralism, advanced metallurgy and animal style art have been detected at the cemetery of Liushui (circa 1100–900 BCE), in the Kunlun Mountains of southern Xinjiang. The authors remind us that these cultural and economic patterns are repeated in many other regions of north Inner Asia as well. The authors also refer to Wagner’s (et al. 2011) hypothesis that a steppe-style economy which penetrated the Kunlun consequently spread throughout the Himalayan region by 800 BCE.

The authors discuss findings made by a joint Sino-American team from Khardong (Mkhar-gdong) in Western Tibet, in 2004. The authors call this site “Kyung-lung Mesa”, which is characterized by the remains of many residential structures as well as refuse pits. From two structures at the site, the researchers compiled calibrated dates of 220–334 CE and 694–880 CE, indicating that Khardong was occupied for centuries.

A number of plant and animal species were identified among the remains of Khardong by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. Botanical remains include a barleycorn and barley rachises, free-threshing wheat caryopses (T. aestivum/turgidum), buckwheat nutlets (Fagopyrum sp.), foxtail millet, a single pine seed coat (Pinus yunnanensis/tabulariformis), and a variety of wild herbaceous seeds. The pine seed is said to be morphologically related to varieties of pines with edible seeds found in southeastern Tibet. From the archaeobotanical evidence collected, it is not clear whether the barley is of the naked or six-rowed variety. The small size of the buckwheat nutlets recovered at Khardong, encourage the authors to believe that they probably belong to a wild species. However, it is not known if the buckwheat remains were brought to Khardong for human consumption, or if they appear in the deposits through dung burning or seed rain.

The authors believe that the relatively large amounts of goat and sheep dung found at Khardong are likely to indicate the penning of the animals, thus pastoralism. The authors hold that the occurrence of animal dung along with barley and buckwheat rachises and chaff points to the economy of Khardong as being based on a mixed agropastoral system of considerable complexity. This agropastoral system developed by the second or third century CE, say the authors. Moreover, the bones of small fish from the site suggest that fishing took place locally. Foraging at Khardong is represented by the pine nut shell, wild raspberry seeds and possibly Potentilla seeds.

D’Alpoim Guedes et al. observe that the eventual adoption of Southwestern plant domesticates in Tibet was facilitated by the frost resistance of barley and wheat, something not shared by millet. As is well established, the authors note that the short growing season for barley (60–100 days) and its robustness in the face of low temperatures and persistent frost make it ideally suited for cultivation on the Tibetan plateau. In conclusion, the authors reiterate that a highly diversified subsistence economy composed of hunting, fishing, foraging, pastoralism, and agriculture developed in Western Tibet and across the entire Plateau.

My Comments on the Article by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. 2014

Here I append a few brief comments. I intend to pursue topics touched upon here in more detail in the not-too-distant future. What is clear in any case is that Tibet is vast and archaeological inquiry is still in its infancy.

As the authors of “Moving agriculture onto the Tibetan plateau: The archaeobotanical evidence” acknowledge, archaeobotanical evidence for the introduction of agriculture in Tibet is limited to a very small handful of sites. Moreover, evidence from some sites was collected in ways that are methodologically weak. Thus, the chronology suggested by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. for the introduction of western plant domesticates such as barley, wheat and peas in Central Tibet requires further corroboration from the field.

Given what is known about the introduction of western domesticates in Kashmir and eastern Central Asia, a period earlier than 1400–900 BCE for the like to occur in Central Tibet should be entertained. Nevertheless, the documentation of early or middle phase Neolithic sites in Central Tibet is still hazy and what kind of agriculture might have been practiced in them is still unknown.

Derived from the controlled analysis of botanical materials, d’Alpoim Guedes et al. have determined that Western Tibet had a highly diversified agropastoral economy by the third century CE. How the domestication of yaks fits into this picture, however, is still unclear. While sheep and goat rearing appear to have originated in southwest Asia, the taming of wild yaks and subsequent stockbreeding is much more likely to have arisen on the Tibetan plateau itself.

A preliminary survey of the highly varied assemblage of material objects obtained from Khardong and from nearby tombs at Gurgyam dated to the same general period (circa 130–350 CE) as the botanical samples studied by d’Alpoim Guedes et al. support the characterization of its economy as advanced.* The existence of silk in a Gurgyam tomb indicates that trade or exchange with north Inner Asian regions was taking place in the third century CE. In other tombs excavated in Guge, dated to 500–100 BCE, bamboo and birch bark objects were discovered. These floral materials point to trade and exchange with moister cis-Himalayan regions.

For details, see the October 2010 and April 2012 Flight of the Khyung.Given the picture of interregional relationships emerging for Khardong, circa third century CE, perhaps the origins of the pine seed and buckwheat remnants found there are best traced to western Himalayan regions such as Kinnaur. At least in the contemporary period, buckwheat is cultivated and pine nuts flourish in lower Kinnaur. Kinnaur (and Uttarakhand) are adjacent to Guge, and seeking the source of buckwheat and pine nuts there rather than in faraway southeastern Tibet may prove fruitful to researchers. I hasten to add that only through macrobotancial and molecular analyses of Western Himalayan pine nuts and buckwheat will their potential role in the ancient Western Tibet economy be determined.

As for the later period of occupation at Khardong (694–880 CE) recorded by d’Alpoim Guedes et al., this squarely coincides with the imperial period, suggesting that Khardong had become a garrison for troops or an administrative center of the Tibetan emperors (btsan-po). Forward lines of command and control were necessary for the invasion and conquest of Ladakh, northern Pakistan and Wakhan in the 8th century CE, and we might see the Khardong of this period fitting into that strategic pattern.

Evidence for fishing found at Khardong dovetails with an Old Tibetan Chronicle account of Semarkar (Sad-mar-kar), a Tibetan princess (btsan-mo) married to the Zhang Zhung ruler Liknyahur (Lĭg-myi-rhya), in the 630s CE. Semarkar went on a fishing trip to Lake Manasarovar (Mtsho ma-pang), but she also complained bitterly about the fish diet served at the castle of Khyunglung (mkhar Khyung-lung), a site best identified with Khardong.

As it now stands, the origins of Southwestern Asian plant domesticates in Western Tibet are highly obscure. High-quality archaeobotanical data for Western Tibet comes from only one site and that thanks to d’Alpoim Guedes et al. There are scores of residential and ceremonial sites in Western Tibet of the same period or older (Iron Age and Protohistoric period) than Khardong that could be examined for ancient botanical and zoological traces.

It remains to be seen how archaeological sites I have documented can be correlated to the carrying of western domesticates to Tibet. A tomb at a necropolis with arrays of standing stones in eastern Ngari has yielded a calibrated date of circa the 9th or 8th century BCE.* As I have shown in my various writings, these types of funerary sites have morphological affinities to the pre-Scythic menhirs or deer stones of north Inner Asia, which recent archaeological work shows began to be erected circa 1200 BCE. Animal style rock art in northwestern Tibet indicates that cultural interactions between Upper Tibet and north Inner Asia were taking place perhaps by the Early Iron Age (circa 900–600 BCE).** The foreign cultural and technological contacts incumbent in these necropolises and rock art may possibly be related to the spread of western plant and animal domesticates.

See Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet, p. 91 (see below for bibliographic details).Also see Antiquities of Zhang Zhung, site no. C-160:http://www.thlib.org/bellezza/#!book=/bellezza2/wb/b2-1-68/ See the October and November 2014 Flight of the Khyung.

If it is shown that western plant domesticates were introduced in Western Tibet prior to the Iron Age, a likely prospect in my opinion, then, correlation with mascoid and chariot rock art in Ruthok and Guge may be indicated. These rock art subjects also occur in north Inner Asia (and in Ladakh and northern Pakistan), and are generally thought to date to the Middle or Late Bronze Age (2000–1000 BCE). A more conservative estimate of the age of mascoid and chariot rock art in Upper Tibet might be prudent (1200–500 BCE), but without the means to securely date this art, this cannot be confirmed.

Archaeobotanical and archaeozoological research in Ladakh and Xinjiang is critical for understanding the spread of western domesticates in Western Tibet. Unfortunately, very little of this work seems to have taken place to date. These contiguous regions have been shown to be instrumental in the propagation and transformation of Bronze Age and Iron Age artistic motifs of a transcultural scope, which appear to have been subsequently transferred to Western Tibet.* Likewise, as regards domesticates in Western Tibet, Ladakh and Xinjiang may well have played a transmissive role.

See:2013. With Bruneau, L. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS:http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

That there is some kind of correlation between the dissemination of north Inner Asian art forms, funerary ritual monuments and western plant and animal domesticates in Western Tibet seems assured. It can be readily imagined that the establishment of agriculture and the more powerful and diversified economy it engendered was necessary for the construction of the archaic citadels of Western Tibet. It must be remembered that almost all of these strongholds are situated near erstwhile agricultural enclaves. As they occur in the same areas, it can also be envisaged that some of those who created mascoid, chariot and animal style rock art in Western Tibet also cultivated crops, as part of a suite of cultural and technological legacies originating from abroad. Other elements of this suite of Eurasian legacies may have possibly included the introduction of the domesticated horse, equestrian technology, knowledge of wheeled vehicle construction, advanced metallurgical techniques, more stringent social hierarchies, and a masculinization of the pantheon, among other things.

The challenge now before us is to expand the scientific data available and to place it in a secure chronological context. Until that is done the prospective scenarios I have drawn here will remain in the realm of hypotheses.

Next Month: Tibetan ceramics from the Neolithic and Metal Age objects exhibited in the Tibet Museum collection!