January 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Flight of the Khyung wishes all users of this website a productive and salutary New Year! To ring in the new, this issue delights readers with two images of the ancient khyung or horned-eagle from uppermost Tibet. The second offering in this newsletter is simply a definition of Bon, an often misunderstood term due to its disparate historical and religious connotations.

The third and longest article features never-before-seen Buddhist murals from western Tibet. Sadly, they are no longer intact, spotlighting a tragedy besetting all of Tibet: the unrelenting destruction of its cultural heritage. Increasingly, ancient monuments are being razed by hungry developers, rock art and Buddhist frescoes despoiled by vandals, and tombs and chortens smashed open by thieves looking for valuable objects. The problem is worsening, compounded by the inaction and ignorance of those appointed to safeguard Tibetan culture. Some of the archaeological sites I have documented over the last two decades no longer exist. They will never be studied more deeply, nor inspire others by their presence. That is truly a great shame.

The fourth and final article looks at ancient equine art in Upper Tibet, as manifested in stone objects. This art of the equid is as distinctive and handsome as that of any other Eurasian culture of yore.

More Ancient Khyung in the Rock Art of Upper Tibet

For your good auspices, I present two rock art images of what appear to be khyung, the ancient horned eagle of Zhang Zhung fame. For other early khyung images, see the January 2012 and January 2013 issues of Flight of the Khyung. The rock art illustrated in these newsletters confirms Tibetan literary accounts (especially Bon ones) that speak of the horned eagle god as having prehistoric (pre-7th century CE) religious origins. The khyung as a genealogical and tribal symbol of the Zhang Zhung kingdom, held an especially prominent place in Upper Tibet. As a Yungdrung Bon and Buddhist protector and tantric figure, it is propitiated by Tibetans right down to the present day.

Fig. 1. A soaring khyung. Note the pair of large horns that extend well above the tips of the wings. Iron Age (or possibly a little later).

This carving of a raptor has outstretched wings, a long neck, broad body, and even wider tail. The beak faces to the right but it is highly eroded and merges with the adjacent wing. We can only speculate why an artist carved this horned eagle in stone, drawing from Tibetan literary and ethnographic sources. Tibetan legends claim that horned eagles once flew in the skies above Tibet, but this seems hardly possible. Perhaps the horned eagle is based on an extinct species of an especially large bird-of-prey with prominent horn-like feathers on its head. In our times, the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) is a good example of an avian species with conspicuous horn-like ear tufts.

The horns of the khyung are probably best seen as a stylistic transformation of the crest feathers or ear tufts of certain raptors. Their creation is likely to have been inspired by the wild ungulates of the Tibetan plateau, which were particularly plentiful in the high plains of the north and west. In ancient Tibetan literature and in common folk practices, animal horns have protective functions against demons and serve as vessels for deities. Placing them on eagles enhances the glory, power and stature of this bird, acting as a potent mythological symbol of religious, tribal, and national identity.

Fig. 2. This bird carved in profile has three corniculate lines extending from the top of its head. The body is filled with an attractive ocular design. Iron Age.

The ‘horns’ of this bird resemble those found on the heads of human figures at other rock art sites, which are also related to the khyung (for example, see figs. 13 and 14 in August 2014 Flight of the Khyung). In number, form, and position, the long tail feathers complement the horns. The bird is depicted with two legs. This carving together with another one of a horned eagle immediately above it and other figures was first published in Antiquities of Upper Tibet, p. 216 (fig. 17), but the bird illustrated here in fig. 2 is barely noticeable in that photograph.

A Definition of Bon in 358 Words

What is and what is not meant by the word Bon has never been fully settled. Tibetologists, comparative religion specialists, and religious practitioners all have their own thoughts on the significance of the term. Recently, in a work contracted by Oxford University Press, I composed a short essay on Bon, succinctly describing the various shades of meaning encompassed by it.

For revised definition, see October 2015 Flight of the Khyung

Senseless Greed: The irreparable loss of the ancient Buddhist murals of Mangdrak

Introduction

In the October 2009 issue of Flight of the Khyung, I publicized the destruction of Buddhist murals at Mangdrak (Mang-brag), a cave site in Guge, far western Tibet. At that time, I was only able to reproduce a photograph taken by D. Ott of the then recently vandalized cave temple. According to Ott, many of the ancient frescoes had been destroyed in that attack. Evidently the motive for this destruction was profit. The thieves attempted to remove the frescoes from the walls but things went badly wrong and most fell to the ground and shattered into a multitude of pieces. Many have since been pulverized into dust. I was very fortunate to be able to visit Mangdrak in 2001. On May 10th of that year, I expended nearly a full roll of film on the wall murals, a considerable expenditure, as the documentation of pre-Buddhist archaeological sites was the main priority of that expedition.

Had I any inkling of what would befall the murals of Mangdrak some years later, I would have attempted to photograph each and every figure individually. As it now stands, my photographic coverage of this art is spotty at best.

For years photographs of Mangdrak were stored in my archives unseen by anyone else. It was only recently that I was able to retrieve and digitize the images in order to present them here to readers. I know of no other scholar or traveler who visited Mangdrak before its priceless art was turned into a heap of earth. I very much hope that somebody did see the site and that my photographs of the intact murals are not the only ones in existence.

Mangdrak is also the name of an ancient community, the ruins of which lie near the eponymous cave. It is said to be named for the variegated cliffs at the locale, but I do not know how well rooted historically this etymology is. Mangdrak is situated on the north bank of the Sutlej river (Glang-chen gtsang-po), just above where it enters an impassable gorge.

East of Mangdrak are four other abandoned communities extending for 12 km along the north side of the Sutlej river, established (or reestablished) during the expansion of Buddhism in the region. They contain ruined temples, castles, cave complexes, and other derelict residential and ceremonial structures. Agriculture was once extensively practiced in these villages. Apparently, because of a lack of water, the fields were discarded. In the oral tradition, it is said that [in 1630 CE] an invading army from Ladakh (La-dwags) destroyed whatever was left of Mangdrak village and the contiguous population centers. There was also an earlier invasion of the area in the 16th century CE by a combined army from other Upper Tibetan regions. More recently, the TAR (Tibet Autonomous Region) government has tried to reintroduce agriculture in the area.

For a description of these abandoned communities, see Antiquities of Zhang Zhang, vol. 1, Tsarang (site no. A-62): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza/#!book=/bellezza/wb/b1-1-15/

Built of mud brick and rammed earth, Mangdrak and the other communities on the right bank of the Sutlej appear to have come up with the florescence of Buddhism in Guge, beginning in the late 10th century CE. These settlements from east to west are as follows: Karu (Ka-ru), Giri (Gi-ri), Gogyam (Sgo-gyam), Sergam (Gser-sgam; the prevailing spelling), and Mangdrak (N. lat. 31° 30.44´ / E. long. 79° 25.28´).

Across the river from the eastern end of these ancient villages is Tsaparang (Rtsa-pa-rang), one of Guge’s most famous monasteries and citadels. Ten kilometers further upstream is Tholing (Mtho-lding), the mother monastery of western Tibet. Thus, 500–1000 years ago, Mangdrak and her sister communities were part of the heartland of the Guge kingdom and its Buddhist religion and culture.

I will present the images of Mangdrak with a minimum of commentary. My specialty is not Buddhist art history and I am unable to make further inquiries on the subject at this time. I trust the pictures will be largely self-explanatory, especially to experts and connoisseurs of western Tibetan mural art. The small cave (4 m x 4 m) at the geographic center of Mangdrak was fully enrobed with murals of lamas (the Bka’ gdams-pa and Sa-skya sects were predominant in the region), protector deities (srung-ma), tutelary gods (yi-dam), buddhas (sangs-rgyas), bodhisattvas (byang-chub sems-dpa’), and sky-treaders (mkha’-’gro), among other figures.

The murals of Mangdrak appear to have been painted at the same time. This Buddhist art can be attributed to the 1200–1400 CE period. Black, gray, white, and red pigments predominate. There is a conspicuous absence of the colors blue and green at the site. It appears from earthen platforms in the rear of the cave temple that statues were once installed.

The art of Mangdrak has the appearance of being made by native artists. Although they were competent painters, the workmanship is not of the high standard encountered at sites such as Tholing monastery, a major religious and political center in Guge during the second diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet. The small size of the Mangdrak temple and the quality of its art suggests that this religious facility catered primarily to local residents, inspired by the dramatic religious developments around them.

Gallery of Frescoes

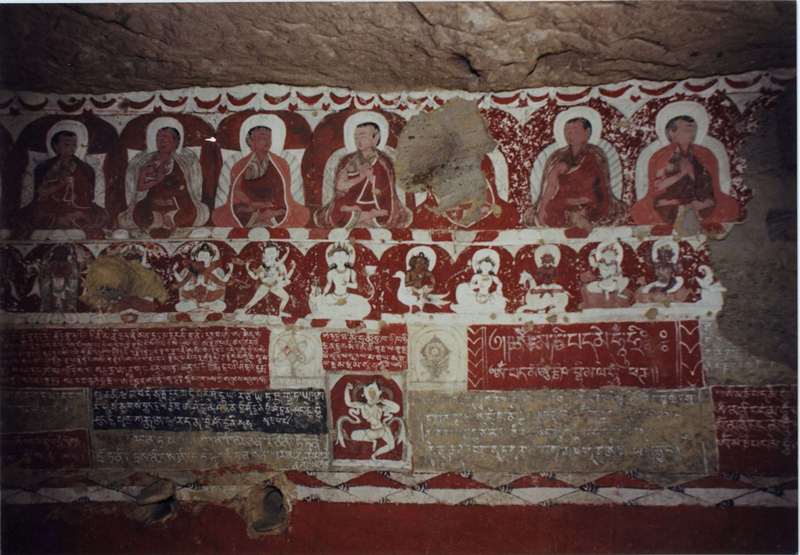

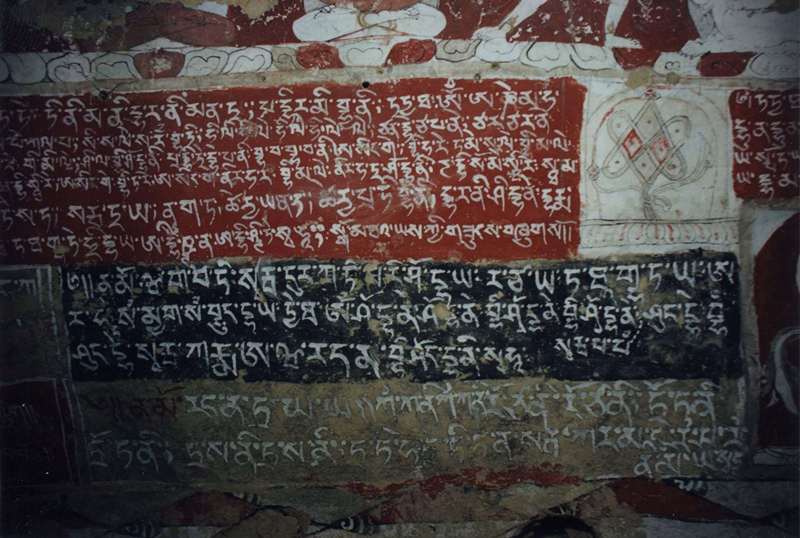

Fig. 4. Part of two walls of the cave temple of Mangdrak, with paintings of lineage lamas, deities in ecstatic embrace and other divine figures, as well as inscribed mantras and prayers.

Fig. 5. A better view of some of the same figures in fig. 4 and others to the right of them. As one can see from these photographs, Mangdrak had already sustained some damage to its art before the catastrophic attack of the late 2000s.

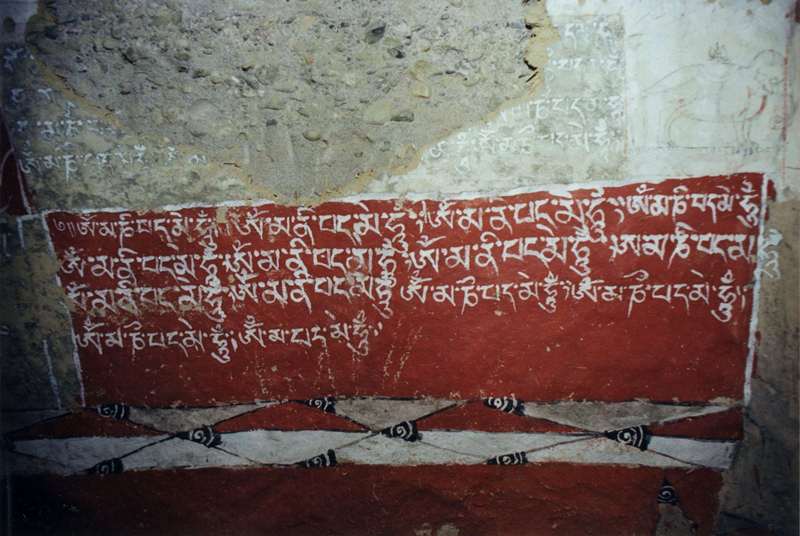

Fig. 6. A close-up of figures in fig. 5. The six-syllable mani mantra and others can be read in this photograph. Note the zi (gzi) stone-like motifs in the border below the paintings. To the left of this mantra is a painting of a dharma wheel (chos-’khor).

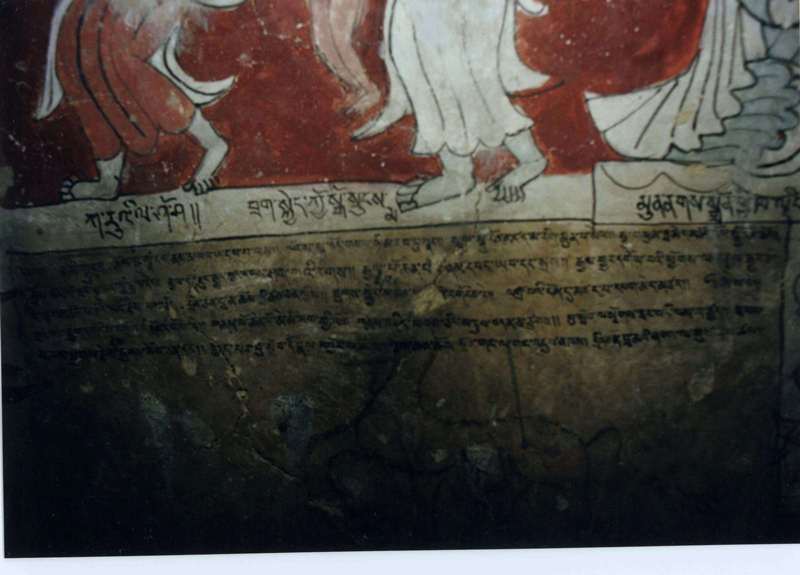

Fig. 7. A detailed view of some of the mantras inscribed below the paintings of lamas and divinities. Note the endless knot (dpal be’u) drawn in a style that is also seen in copper alloy amulets and other art of the same period.

Fig. 8. A panel of Tibetanized Sanskrit mantras situated to the right of those in fig. 6, which reads: tatya tha mi hu mi hu kha hi kha hi…

Fig. 9. A close-up view of the dharma wheel and panel with mani mantra seen in fig. 4. The Om syllable in the large uppermost mani mantra was written in a style prevalent before the 14th century CE. This style of script has a ma consisting of two components, rather than one which has been standard for the last 700 years or so.

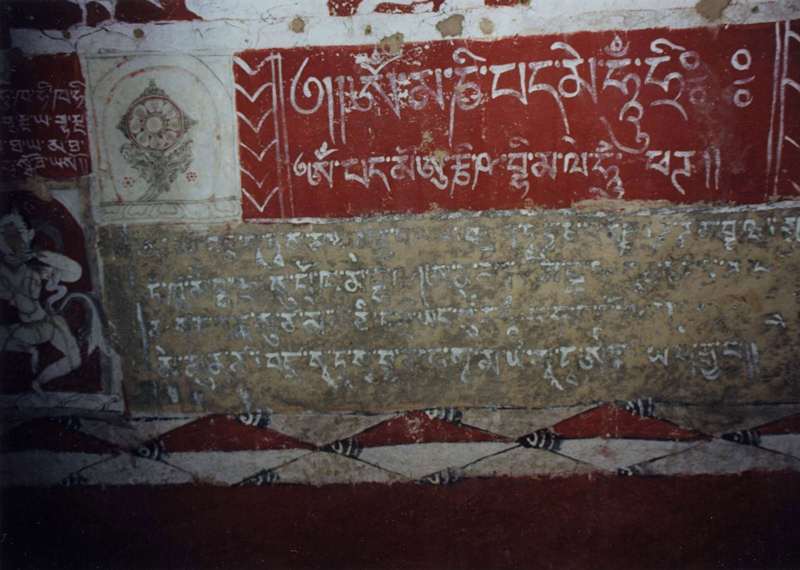

Fig. 10. In the center of this section of murals is the eleven-headed bodhisattva of compassion Chenrezik (Spyan-ras-gzigs). Other figures seen include buddhas and lamas.

Fig. 11. Tutelary deities (including Heruka) in ecstatic embrace (yab-yum) and bodhisattvas. At the bottom of the panel is a vase (bum-pa), another one of the eight auspicious symbols of Tibetan Buddhism painted on the walls of Mangdrak. Next to it is the mani mantra exhibiting old-fashioned paleographic characteristics including the cradled ma of the Om and the reverse i vowel sign above the na.

Fig. 12. Some of the murals in this photograph are included in fig. 11 and others in this image are situated to the left of them.

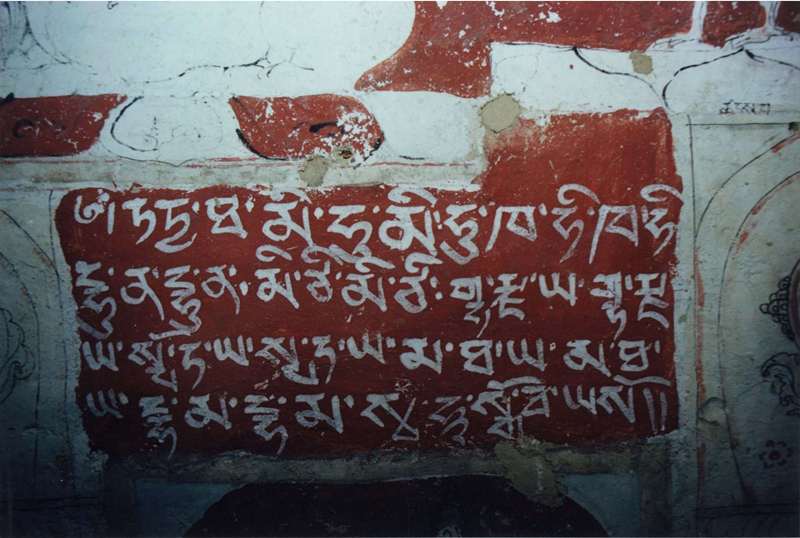

Note the mantras of the bodhisattvas Chakna Dorje (Phyag-na rdo-rje; red background) and Jampayang (’Jam-dpal dbyangs; earth-colored background) to the left of the mani mantra of Chenrezik. This trio of famous bodhisattvas is known as Riksum Goenpo (Rigs-gsum mgon-po).

In the depictions of the figures in ecstatic embrace, Khasa Malla or western Nepalese influence is particularly discernable. Thanks to David Pritzker for pointing out this artistic influence, which extends more generally to all of the temple art of Mangdrak. The imprint of the Khasa Malla at Mangdrak is important in dating these murals.

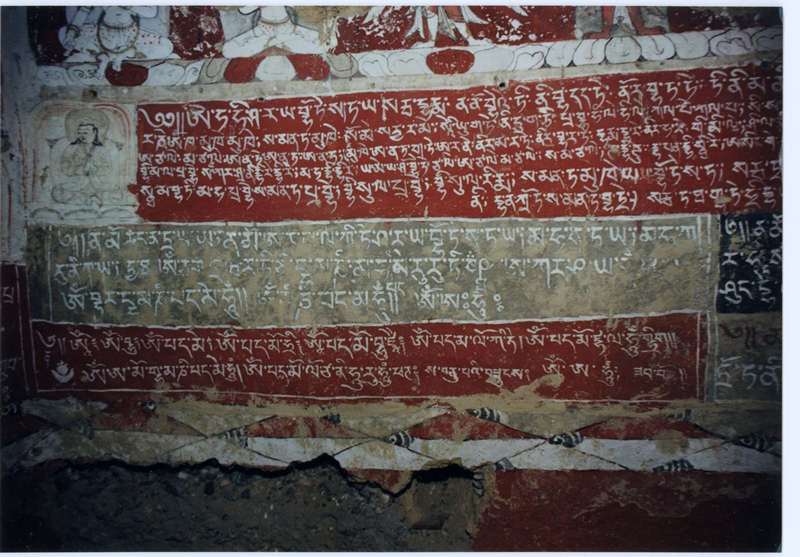

Fig. 13. A variety of divine and human figures. The upper central figure is the historical Buddha Sakyamuni in the earth-witness pose. To the right is a bodhisattva. Even in 2001, a significant portion of some murals had already disappeared.

Fig. 14. Mantras and prayers on a lower register of the murals as well as divine figures also visible in fig. 4.

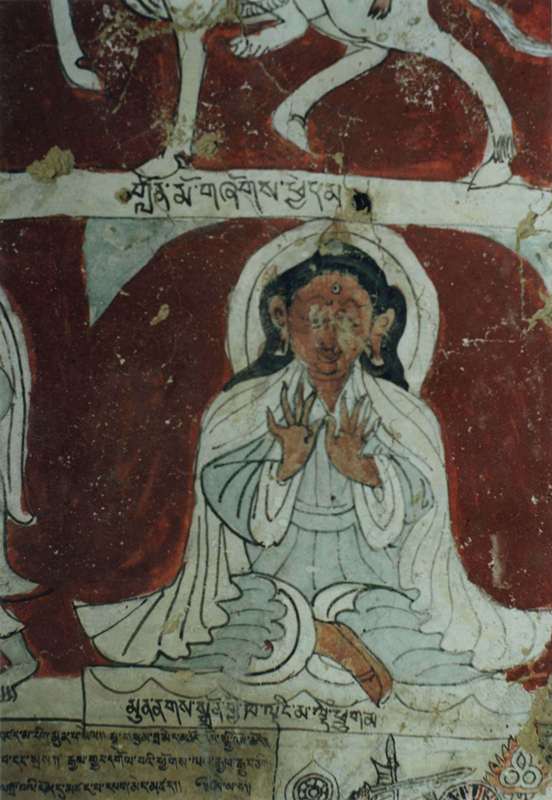

Fig. 15. Another view of the panels in fig. 14. The man dressed in white to the left of the upper inscription appears to be an aristocratic benefactor. He is attired in the dress and turban of a layman.

In the top register are four lama figures and to their right is a god riding a lion. In the middle register there is a line of protective gods, some of which are attired in the costumes of Guge and other regions of western Tibet. Note the goat-headed god on the right end of the middle register. The biggest figure of the lower register is Rahula (Ra-hu-la), the personification of eclipses, positively identified by the accompanying inscription. His body is covered in eyes. In his right hand he holds a scythe and in his left a horn-like object. To the left of Rahula’s heads is what appears to be a water spirit (klu), which is facing in the direction of a territorial or warrior god dressed all in white and mounted on a horse. The large animal-headed figure next to Rahula seems to be pushing against both a red demon sandwiched between it and Rahula and Rahula himself. This may signify the astrological regulation of Rahula, who is perceived as an extremely wrathful figure.

These mantras were written in a time when the i vowel sign commonly faced in both directions. This paleographic period is also indicated by the ma in Om, which alternatively exhibits both obsolete and modern conventions on the same panel. This mix of graphologic conventions is also found on copper alloy plaques embossed with the mani mantra from the same timeframe (these were worn by Tibetans as amulets).

Fig. 18. Local protective deities (yul-lha) and other divine figures located on the wall beside the entrance to the cave temple.

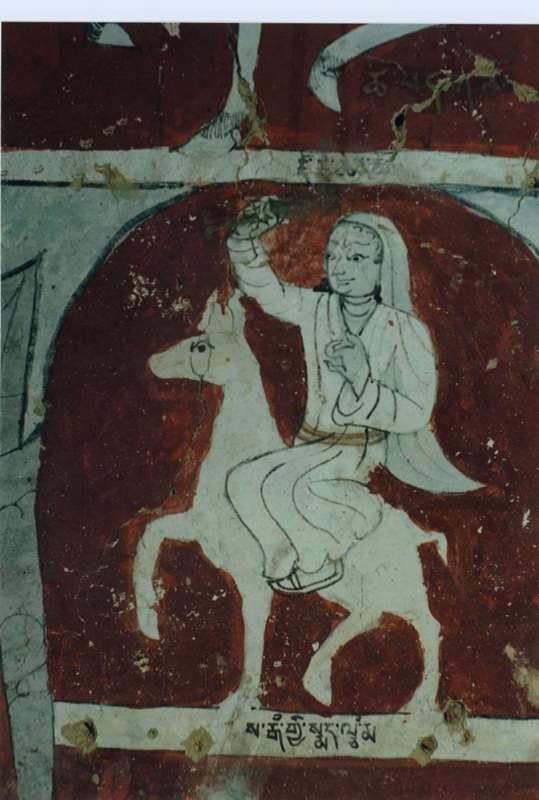

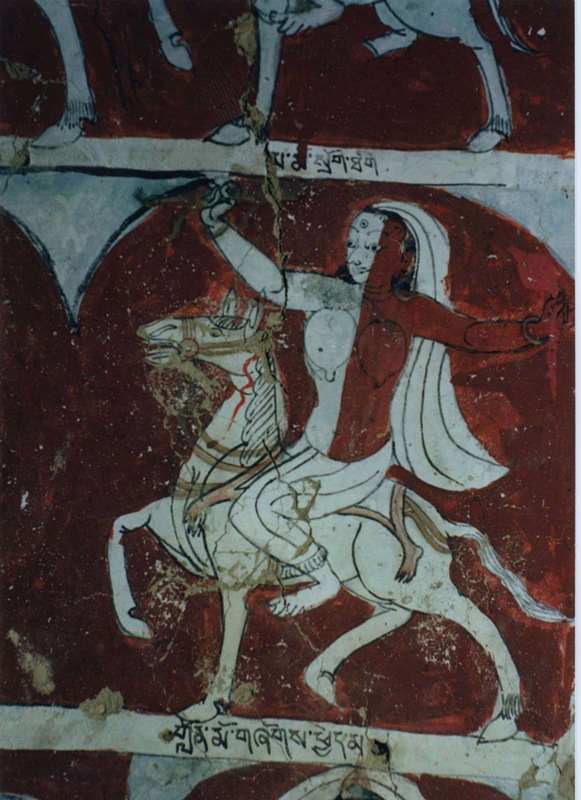

During my visit to Mangdrak, I was most interested in local territorial deities depicted in murals beside the entrance. Seven of these yulha are shown on horses, while at least two are standing and one seated. The majority of these figures are female, reflecting the predominance of female yulha in southern Guge (Gu-ge lho-smad). At Mangdrak, they exhibit a style of dress and ornaments drawing from cultural traditions of western Tibet, the western Himalaya and the plains of India. In my journal of 2001 (vol. 39) I write: “Historically, I think the [chief] importance of this panel is it graphically demonstrates that in Guge the cult of local deities had become Indianized to some extent in terms of attributes and costumes. This iconographic modification undoubtedly went hand in hand with a doctrinal reorganization of the cult to reflect Buddhist values and sensibilities.”

Inscriptions that accompanied these paintings provided most of the names of the deities. In a few instances, the accompanying inscriptions retained the orthography of Old Tibetan: nags for nag (black) srungs for srung (protector), ru’i for ru yi (of the division), and rgam for sgam (box / chest). It is curious that old-fashioned spellings were used into the 13th or 14th century CE. This may be a result of the provincial nature of the temple and the influence of the local dialect. Sadly, this exceptionally important artwork and the inscriptions have been obliterated.

The size and placement of this figure on the left side of the upper register indicates that it is a particularly important or powerful member of the Guge pantheon. This goddess wears the crown of tantric Buddhism with its five diadems (rigs-lnga). Her hair stands on end. Another Indian feature is the third or wisdom eye (ye-shes spyan). The goddess spews fire from her mouth and brandishes a double-edged sword in her right hand. She is garlanded with shrunken human heads and clad only in a wrap that winds around her loins. A bow appears to be hung across her back. She is mounted on a braying light-colored mule with brown markings. Given her dress, mount and position in the murals, this goddess can be identified as an aspect or manifestation of Palden Lhamo (Dpal-ldan lha-mo), the main protectress of Tibetan Buddhism.

According to the Tibetan art expert David Pritzker (in personal communication), this figure of Shri Devi is done in a classic western Tibetan style, which is particularly seen in the way in which her hair flames up, an iconographic trait that derives its influence from Kashmir. I would also like to thank another scholar of Tibetan art, Ian Alsop, for his comments about Mangdrak.

I have no close-up photograph of the second yulha in the upper register, a female wearing a veil and patterned gown and wielding a scythe (zor-ba).

Fig. 20. The third yulha in the upper register, Dorje Chenmo. In the mural she also carries the epithet Tshedakmo (Tshe bdag-mo), the ‘Mistress of Long Life’.

Dorje Chenmo (Rdo-rje chen-mo) is the yulha of Tholing, which sprung from her role as an important protectress of Kadampa monasteries and interests. She is still a patron deity of Buddhist temples in western Tibet and the western Himalaya. Dorje Chenmo was the tutelary goddess of Lotsawa Richen Sangpo (Lo-tsa-ba rin-chen bzang-po), a lama who made great strides in reestablishing Buddhism in western Tibet, in the late 10th and first half of the 11th century CE. More specifically, Dorje Chenmo was the guardian of Lotsawa Richen Sangpo’s teachings (bka’-srung).

In the fresco from Mangdrak, Dorje Chenmo has a bluish complexion, dons a crown of five diadems and grasps a ritual thunderbolt in her right hand, all attributes of tantric Buddhism. However, much of the rest of her dress and attributes have indigenous Tibetan overtones. She holds a golden vase at her breast, an ancient symbol of long life and prosperity. The draped arrow (mda’-dar) in her left hand is ornamented with lammergeyer feathers (rgod-sgro), multicolored ribbons (dar-sna), and a metal mirror (me-long) with eyes (mig). The draped arrow is a Tibetan ritual instrument used to ward away evil and usher in good fortune.* Dorje Chenmo is attired in a white gown with red trim that opens down the middle, a western Tibetan style of attire. She is ornamented in a golden necklace and earrings (there is not enough detail in the picture to identify their cultural origin). Dorje Chenmo’s white horse with a red mane and tail is caparisoned with golden tack.

For extensive coverage of the draped arrow in Tibetan myth and ritual, see:My book Calling Down the Gods (consult books section of this website for bibliographic details).Samten G. Karmay’s The Arrow and the Spindle: Studies in History, Myths, Rituals and Beliefs in Tibet, Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point, 2009.According to the accompanying inscription, this is Mamo Srogthik (Ma-mo srog-thig), a tantric goddess, holder of the essence of life. Her name and iconography indicate that she had a broader religious role than merely being a territorial deity. Her attributes include a sword (ral-gri), mirror (me-long), staff (kha-tam-ga), and snake (sbrul). Note the eyes along the edge of the mirror. Judging from their spacing, they were almost certainly nine in number, an ancient mythic and ritual tradition. Metal mirrors of this type were commonly produced in ancient Tibet for ritual purposes. Nine eyes symbolize all the modalities or elements of the universe and were thus employed as an apotropaic and good-fortune-bestowing apparatus.

I have no photographs of the two figures on the left side of the middle register. The female on horseback is named Mukgyam Gyi Khalama (Smug-gyam gyi kha-la-ma). She is the yulha of Mukgyam, located on the opposite side of the Sutlej river from Mangdrak. At Mukgyam there is an important archaic installation called Balu Khar (Sba-lu mkhar, Castle of the Dwarfs). Mukgyam Gyi Khalama is a queen-like figure riding on a white horse, and holding a chopper (gri-gug) in her right hand and a snare (zhags-pa) in her left hand.

Fig. 22. The yulha Sargam Gyi Mechamma (Sa-rgam gyi smad lcam-ma) riding a horse. She is located second to the right in the middle register.

This goddess is the territorial deity of the lower portion of the nearby derelict village of Sargam, which is nowadays known as Sergam (Gser-sgam; Golden Chest). Sargam is probably the Old Tibetan spelling for ‘Earthen Chest’. In the goddess’ right hand she grasps an anthropomorphic demonic figure or effigy. Her dress and veil are of western Tibetan or western Himalayan origins.

Fig. 23. The yulha Lönmo Shokchema (Glon-mo gshogs-phyed-ma) who, as her name indicates, is half red and half white in color. She is found on the right side of the middle register.

This goddess also holds a demonic figure in her right hand and possibly organs in her left. She has pendulous breasts and is clad in clothing that is of Indian inspiration.

The large figure on the left side of the lower register has a bird head and holds a ritual thunderbolt in its right hand and a skull cup full of blood in its left. Fortunately, I recorded the name of this god in my journal: Charokdongchen Gyi Dra Oyi Srok Chöpa (Bya-rog sdong-can gyis sgra ’o yi srog gcod pa; Crow-headed One Who By Its Cry Cuts the Life-force).

Fig. 24. Karui Lashosha (Ka-ru’i la-sho-sha), the yulha of Karu, located a few kilometers upstream from Mangdrak. In dress and aspect, this territorial spirit resembles an Indian dancing girl. It is not clear to me what she is holding in her hands.

Fig. 25. Brakkye Kyo Gosungma (Brag-skyed kyo sgo-srungs-ma), the yulha or ‘portal protectress’ of a large rock formation near the village of Sergam.

The goddess is attired in a long gown and veil. She holds up a reddish figure by its hair. This naked male must represent a demon of some kind.

Located on the right side of the lower register, this is the only seated yulha depicted on the rear wall of the temple. She has a halo and a third eye (as do other local deities we have been examining), iconographic traits imported from India. Her hands are held in a gesture of protection or benediction. She is wearing a long robe and cape.

During my visit to Mangdrak, I did not have time to closely examine this inscription. With my current digital copy, it is very hard to make out. A digital scan of the actual negative should produce a better image (the images in this newsletter are from scans of the photographs). The dedication refers to the Female Fire Pig Year (Gnam-lo chen-po me-mo-phag gyi lo), the last of which was in 2007. This recorded year seems to be a reference to when the temple of Mangdrak was founded. Thus, along with a consideration of the style of the murals and inscriptions, we might infer from this calendrical attribution that Mangdrak was established in either 1227, 1287, 1347 or 1407 CE, with perhaps the first two dates best indicated.

Standing Proudly: Early equine art in Upper Tibet

During a recent trip to Lhasa, a collector of ancient art from western Tibet permitted me to photograph three stone stands, which functioned as a tripod for cooking. These heavily patinated hearthstones are decorated with what appear to be the heads of equids.

Fig. 28. Three carved stones of the hearth on which a stone pot rests. These objects were obtained in western Tibet. According to information received by the current owner, the hearth stones are of western Tibetan origins. Private collection, Lhasa.

It is not clear whether the carved tripod stones depict wild ass or horse heads. Given their unusual appearance, perhaps an entirely different creature is intended, but this does not seem to be a strong possibility. The utilitarian function of the stones favored the fashioning of a squat head without sharp projections. These heads have a sleek form, small oval ears, almond-shaped eyes with eyebrows, short muzzle, and an open mouth with circular ends. The three carved stones reveal a distinctive style of zoomorphic art, which appears to be particular to western Tibet.

The hearthstones are designed to be stable but as light as possible by relying on two vertical supports with a large open area between them. This design also makes it easy for the stones to be picked up and moved. The stability of each stone is enhanced by its thick foot, which gradually tapers downward to further reduce weight.

Such a tripod could have been used in homes of western Tibet, but also possibly by wealthier pastoralists, as the stones are quite portable. I am not certain about the age of this figured stone tripod. It may be ancient, even dating to the first millennium CE. Alternatively, such objects could possibly have been made within the last 500 years, representing a folk-art tradition that persisted in western Tibet for centuries. Until more such objects appear (preferably within a secure archaeological context), their provenance and age will be in question.

Traditionally, the hearth in the Tibetan home and tent is fundamentally made up of three stones. According to the ancient mythology of western Tibet and the western Himalaya, these stones arrayed in a circle serve as a recapitulation of the tripartite universe (srid-pa’i gsum). In one interpretation, the hearthstones represent the three main classes of deities of existence: the white spirits of the upper realm (steng gi lha), the red spirits of the middle realm (bar gyi btsan) and the blue or black spirits of the subterranean realm (’og gi klu). The hearthstones are also seen as a vessel or sanctuary of the god of the hearth (thab-lha), an important domestic protector. There is also an ancient protectress of the hearth in Tibet (thab-sman).

The god of the hearth is first recorded in Old Tibetan ritual manuscripts (e.g., Pt 1043, Pt 1047, Gnag rabs). Perhaps the three carved stones featured in this article symbolize the god or goddess of the hearth in the form of an equid, lending them a sacred quality.

Next Month: A tour of pre-Buddhist objects in the Tibet Museum, Lhasa!