July 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung, transporting you to uppermost Tibet! Recently, I had the opportunity to revisit a holy lake in the eastern Changthang renown for ancient rock shelters. These primitive dwellings are believed to have been used by the Bon practitioners of Zhang Zhung. The second article in this month’s newsletter features a set of uniquely designed thousand-year-old Buddhist religious monuments known as chortens. These are the most intricately carved examples discovered in all of Upper Tibet.

A New Map

This is to inform readers that a map showing tomb sites surveyed by Dr. Guntram Hazod in Central Tibet has been added to the May 2014 newsletter feature, Review of the Website Called “Tibetan Tumulus Tradition”. This map was specially drawn for this newsletter by Karl E. Ryavec, a professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin (Stevens Point).

A Bon Stronghold Past and Present: The lakeside settlement of Gyer Ru Tsho Do

West of Nakchu city there are only two major areas with native Bon religious practitioners extending all the way to the borders of India. One of these Bon enclaves is Poche (sPo-che) located northwest of Lake Nam Tsho. Poche is dominated by an approximately 5700 m-tall divine mountain of the same name. According to local folklore, this mountain was a rival for the affections of the goddess of Lake Nam Tsho. In a fit of jealousy, the husband of Nam Tsho, Mount Nyenchen Thanglha, cut off the top of Poche. This tale is told to explain why this mountain has a flat top. In textual accounts, Mount Poche is a territorial deity and the northern general of Nyenchen Thanglha. For more lore about Poche, see my book Calling Down the Gods (bibliographic information is available in the “Books” section of this website).

Fig. 1. Mount Poche from the west, as seen from the summit of the headland known as Gyer Ru Tsho Do.

Twenty kilometers west of Poche is a small sacred lake, which nowadays is called Coral Lake (Byu-ru mtsho). The Bonpo maintain however that this name is a corruption of the original appellation: Gyer Ru Tsho (Gyer-ru mtsho). Gyer Ru Tsho translates something to the effect of ‘Bon District Lake’ or ‘Bon Community Lake’. The old name is said to reflect the significance of this body of freshwater to the religious predecessors of today’s Bon religion. According to Bon tradition, Gyer is the Zhang Zhung language equivalent of the term ‘Bon’.

In particular, the three-kilometer-long headland known as Gyer Ru Do that bisects Gyer Ru Tsho is thought to have been occupied by adepts since early times. Local tradition has it that the famous 8th century CE Bon saints Nangsher Löpo (sNang-bzher lod-po) and Gyerpung Drenpa Namkha (Gyer-spungs dran-pa nam-mkha’) meditated at Gyer Ru Tsho Do. Although this association of great saints with the headland at Gyer Ru Tsho cannot be independently verified, the archaeological evidence does indeed indicate that this lake has been a magnet of human settlement for a long time.

At Gyer Ru Tsho Do there is a cave that has been in use as a place of meditation for at least several centuries. This hermitage (called bsam-khang: ‘house of meditation’) is known as the Elephant Cave (Glang-chen phug). It is named for the formation in which it is found, one that is thought to resemble an elephant. Beautifully situated on the south side of Gyer Ru Tsho Do, in this period of diminished religious activity, Elephant Cave now lies vacant. Nevertheless, this cave is still maintained by Bon devotees as a palpable symbol of their august past. Meditators from Menri Ling (sMan-ri gling) and more recently those of Rulak Yungdrungling (Ru-lag g.Yung-drung gling), in Tsang (gTsang), have frequented this cave. Even before the foundation of Menri Ling in the 15th century CE, an ancient Bon sage called Langchen Tshampa (Glang-chen mtshams-pa) is supposed to have meditated at Gyer Ru Tsho Do. In the late 1940s, Elephant Cave was home to Lopön Tenzin Namdak. Now Bon’s senior-most scholar, The young Lopön Tenzin Namdak stayed at this retreat site with his spiritual master Gang Ru Pönlob (Gangs-ru dpon-slob).

Fig. 3. Elephant Cave, Gyer Ru Tsho Do. As can be seen in this image, the cave is divided into two parts. The right half functioned as a kitchen and fuel storage area and the left half (with large window) was used for religious practice and sleeping. The latrine is located below the kitchen.

In the mid-1990s, I conducted a series of interviews with Lopön Tenzin Namdak regarding his stay at Elephant Cave, clearly a seminal event in his life. In the book Divine Dyads, I write:

…The young Lopön Tenzin Namdak lived at Gyer Ru Tsho with his master the then head scholar of Bon, Tshultrim Gyaltsen (Tshul-khrims rgyal-mtshan), better known as Gang Ru Pönlob. It was at this time that Lopön Tenzin Namdak acquired tremendous first hand experience of Nam Tsho and the adjoining areas. He became fluent in the language of the Apa Hor (name of the tribe of shepherds in the region) and learned a great deal about their history and culture. While a debate revolves around the historicity of the Zhang Zhung kingdom in Western academic circles, for the Lopön, his stay at Nam Tsho and later at Dangra Yumtsho proved without a shadow of a doubt the existence of this ancient kingdom. He found it evident in the legends, customs, religion, and language of the shepherds (’brog-pa), and in the physical remains of ruins and in caves. No longer merely a matter of Bon orthodoxy, Zhang Zhung took on a tangible and credible identity for the young scholar… Gang Ru Pönlob and his disciple were part of the culmination of a Bon cultural renaissance in the region. Theirs was essentially an effort to reclaim ancient Bon-po territories…

The archaeological evidence at the many headlands of Lake Nam Tsho, Gyer Ru Tsho Do and other places in the eastern Changthang does indeed demonstrate that the region enjoyed a vibrant cultural life before the advent of Buddhism. As many readers will know, I have charted this ancient heritage in a series of books, papers and in the pages of this newsletter. While the political affiliations of the eastern Changthang before the unification of Tibet under King Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century CE remain unclear, the archaeological record points to a unique Upper Tibetan cultural formation. On this basis, I have suggested that a relationship with Zhang Zhung and its smaller sister kingdom Sumpa, as described in Tibetan literature, as being plausible and of significant interpretable value.

Gyer Ru Tsho Do is not one of the Changthang’s larger or more spectacular archaeological sites. This blue limestone headland rises a maximum of 60 m above the lake but most of it is 30 m or less in height. Gyer Ru Tsho and the headland are relatively small and so are traces of ancient settlement in this locale. These remains take the form of cave shelters developed over time in various phases of settlement activity. Some of the eight or nine rock shelters of Gyer Ru Tsho Do were exploited in the historical era, while others appear to date to the pre-7th century CE prehistoric era and to have been abandoned in the distant past.

Even in its most developed phase, the rock shelters at Gyer Ru Tsho Do could not have supported more than several dozen residents. The existence of this site shows that even headlands with more modest geographical qualities were exploited as permanent habitations, provided they possessed certain physical attributes. These attributes are both practical and geomantic or mythic in nature, and include lakes containing potable water and south-facing headlands overlooking expanses of water to the east. The importance of potable water is self explanatory, as is a southern aspect in a cold northern hemisphere climate. Orientation over a body of water to the east is probably best explained by ritualistic and ideological factors. The placation of lake goddesses and the sun rising over water appear to be relevant considerations in this regard.

I first surveyed Gyer Ru Tsho Do in 1999. In the fifteen years since then, I have developed a more refined typology of rock shelters. This year I was keen to apply that knowledge to the ruins at Gyer Ru Tsho. For the initial survey of the site, see my book Antiquities of Northern Tibet.

Fig. 4. Locus I, a rock shelter on the north side of Gyer Ru Tsho Do. Note the remains of the masonry walls that once sealed the cave.

There is just one cave on the north side of Gyer Ru Tsho Do. I call this site locus I. Despite receiving far less sunlight than places on the south side of the headland, this cave (5 m x 3 m) was modified for human habitation. It is situated near the rocky summit of the headland and is barricaded by the remains of a masonry facade. Like most other manmade walls at Gyer Ru Tsho Do, this was a quite heavily built structure composed of double-coursed, dry-stone, uncut limestone blocks. Extending out from the facade are the vestiges of one or two parallel walls, which may have possibly formed an anteroom or landing around the cave. In close proximity to this cave is an unmodified example with a low ceiling and two mouths. Morphological evidence at Locus I is limited, hence the period in which the walls were built is unclear.

Just east of locus I, there is a saddle in the center of Gyer Ru Tsho Do in the otherwise rocky backbone of the headland. Just below the rim of the saddle, on the south side of the headland, is Locus II. A highly deteriorated wall bounds a level area (11 m x 4 m) nestled against a rock face. The wall demarcating the site is freestanding to a height of as much as 1 m. This appears to have been a residential site of the kind found at headlands and islands in Upper Tibet predating the 10th century CE. Nonetheless, the existing structural evidence does not permit a conclusive assessment of the structure.

East of Elephant Cave, towards the tip of the headland, is another zone with what appear to be a series of highly deteriorated walls, which may have belonged to ancient rock shelters. However, there is very little physical evidence left to appraise and any such attribution remains tentative. Elephant Cave itself may have possibly been an early residential site but the Lamaist retreat center has completely engulfed what may have existed there earlier. Areas with possible ancient remains east of Elephant Cave have been assigned the label Locus III.

Fig. 6. The rock shelter at Locus IV. Note the manner in which wall traces continue up the natural ramp of stone on the left side of the structure.

Locus IV is situated west of the saddle and on the south side of the headland. It is set approximately 20 m above Gyer Ru Tsho in an overhang of the escarpment. A wall up to 1.5 m in height on its exterior side encloses a triangular space (5 m on each side) underneath the overhang. The forward wall runs up a natural stone ramp, a design feature found at archaic rock shelter sites in Upper Tibet. If this ramp of stone was fully enclosed by walls, it would have added approximately 6 m² to the residential structure. In the cliff face there is a quite recognizableself-formed (rang-byon) swastika, a local sacred feature of the Bonpo. In a recess to the east are two highly exfoliated counter-clockwise swastikas painted in red ochre. These pictographs mark the ancient tenure of the site by those practicing an archaic form of religion.

Fig. 8. The interior of the cave at Locus V. Note the wall in the foreground dividing the forward and central portions of the cave. In the background the shut in rear of the cave is visible.

Locus V of the Gyer Ru Tsho Do headland consists of a V-shaped crook in the escarpment elevated about 15 m above the lake. A cave with a heavily mud-mortared facade forms the nucleus of the site. The fabric of this facade strongly suggests a historical religious origin. Prayer flags have been hung inside and outside of this cave and votive clay plaques (tsha-tsha) deposited in the interior. While it does not appear to have a name, this cave retains a religious status in the sacred geography of the Bonpo. Five stone steps lead up to the 1.4 m tall entranceway of the cave. Relatively large doorways are another trait associated with historical architecture. The cave is divided into three sections: forward (open space 4 m long), central (3 m long, with masonry partition wall and entablature) and rear (narrow immured space probably with a ritual function). In front of the cave are a series of manmade terraces which cover at least 100 m² and have a total height of 5 m. These remains appear to be those of anterior structures. While the walled terraces have virtually disappeared over time, the cave itself indicates that these may have had residential significance in ancient times.

Fig. 9. Structural remains at locus VI, Gyer Ru Tsho Do. Note the intact standing wall enclosing the cliff on the upper right side of the image.

Locus VI is located at the base of the limestone escarpment. Fragmentary foundations and revetments create a level space, 3 m to 5 m wide, running along the cliff for more than 20 m. On the basis of its aspect, design and construction, this presumably was an archaic residential complex. The formation partly overhangs the site. On the east end a wall fragment up to 1.8 m in height clings to the cliff, the only fully standing ancient structure surviving at Gyer Ru Tsho Do.

Fig. 10. The horizontal fissures of Locus VII situated near the summit of the escarpment, Gyer Ru Tsho Do. Access to points west is via a narrow ledge on the left side of the site. This restricted access lends an impregnable quality to Locus VII.

Fig. 11. Forward and inner walls in the central fissure of Locus VII, Gyer Ru Tsho Do. The aspect and design of this construction strongly suggests an archaic cultural identity.

Locus VII is the most westerly one on the Gyer Ru Tsho Do headland. It is comprised of several horizontal fissures in the escarpment perched 15 m to 20 m above the lake. A centrally located fissure is surrounded by wall traces reduced to 50 cm or less in height. These walls demarcate an internal space (approximately 8 m x 5 m), which is divided in half by another wall. An outer wall, at a distance of 1 m to 2 m, parallels the forward wall of this structure, the remains it seems of a more extensive structure. Locus VII is quite hard to reach and has a defensible position. Finding protected locations for construction was a preoccupation of archaic builders. Like other loci at the headland, Locus VII is well sheltered from rock falls.

Exquisitely Carved Chortens from Far Western Tibet

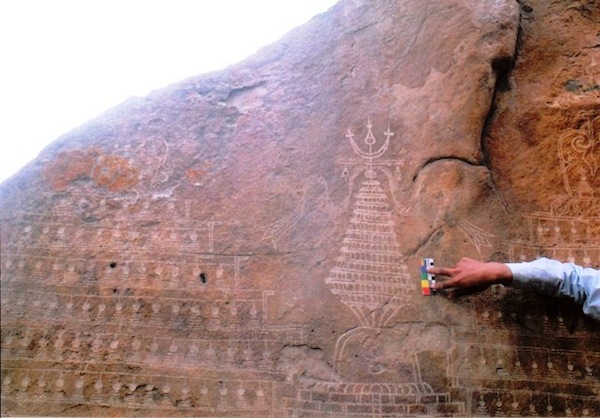

There is a series of beautifully carved chortens (stupa) I discovered in the Guge region of western Tibet about a decade ago. They are located in the remote western corner of the county, not far from the Indian district of Kinnaur, at a place called Gyalading (rGyal-la-lding). The carved chortens here are of much cultural and artistic value. On art historical grounds, these large petroglyphs can be dated to circa 1000–1250 CE. When the focus is on archaic cultural traditions in Upper Tibet, I refer to this particular era as the ‘vestigial period’ (during which the definitive conversion to Lamaism occurred throughout Upper Tibet). However, in the case of the Gyalading chortens and other Buddhist art and architecture of that period there is absolutely nothing vestigial about them. These chortens belong to one of the greatest phases in the history of Tibetan Buddhism. Centered in Guge, this was a time of great cultural and religious attainments that left an indelible mark on Tibetan civilization.

Often referred to as the second diffusion of Buddhism (btsan-pa phyi-dar), circa 1000 CE, Indian philosophy and tantracism burst upon western Tibet in the most dramatic of ways. That which was created in a physical sense bore the marks of all the major cultures surrounding western Tibet and beyond. Thus the Gyalading chortens represent a high-water mark in the carving of reliefs in stone. Of considerable technical refinement, these chortens were part of an artistic tradition in Guge that extended to many different media including painting (on paper, cloth and as frescoes), sculpture and carving (in a wide variety of materials), textiles (of many kinds) and ornaments (also rich in variety).

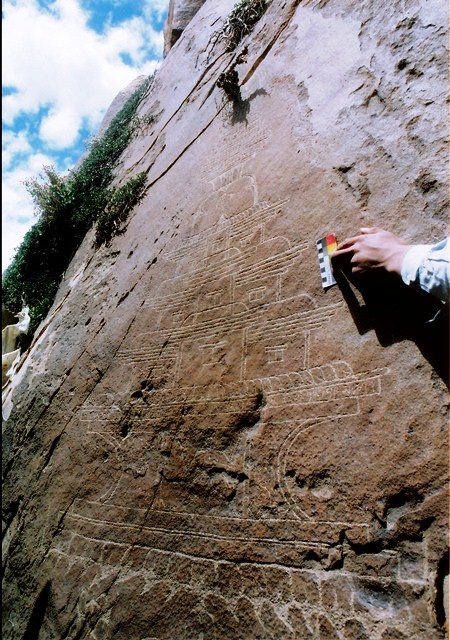

Fig. 13. Partial view of three of the six large chortens carved at Gyalading in far western Tibet. They range in size from around 1.3 m to more than 2 m in height. As I am in the field at the moment, I do not have access to my original research notes with their more detailed quantitative data.

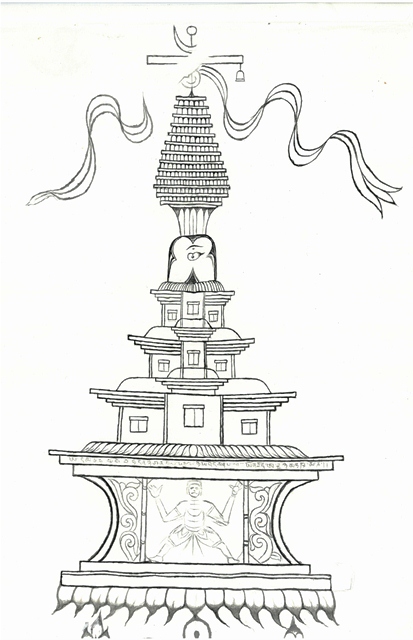

These etchings in stone were difficult to photograph because there is only a narrow space in which to work. The chortens are situated on two vertical boulder faces oriented in opposite directions, with less than a meter between them. Today, with digital photography, more of each chorten could be captured in a single image. To compensate for the limitations of my photography, I commissioned the renowned thangka Tibetan artist Lingtsang Kalsang Dorjee to create black and white drawings of the chortens. Using my photographs he and his atelier have expertly recreated this ancient Buddhist art. I heartily thank them for their excellent efforts. Monies for the commissioning of drawings of this and other Upper Tibetan rock art was provided by the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York). I heartily thank this august institution for its unstinting support of my research work.

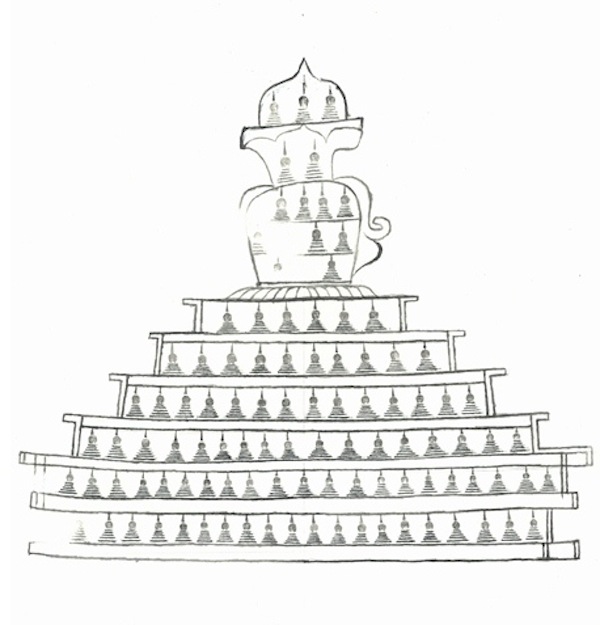

As one can readily see, the body of this rendition of a sacred monument is embellished with a series of horizontally arrayed rows of miniature chortens. There are six such tiers of tiny chortens, an anomalous number. Usually, the base of a chorten consists of a five stepped structure. I have documented a chorten in the Ochang (O-byang) region of Ruthok, which also has rows of miniature chortens inside it.

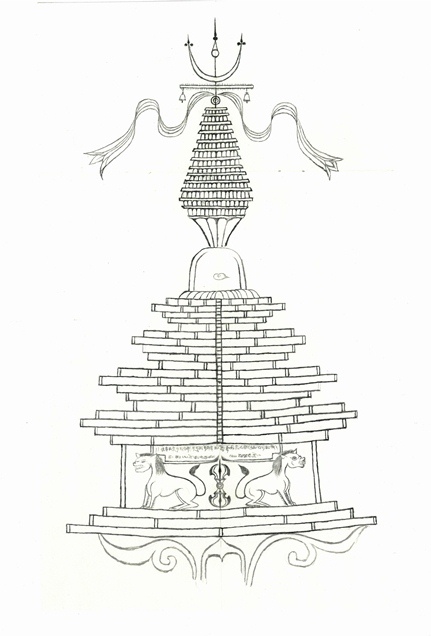

This unique specimen has an unusually designed finial (tog), consisting of a highly stylized conjoined sun and moon (nyi-zla). While this motif is standard in Tibetan Buddhist chorten design, this particular example retains a horn-like appearance, recalling archaic ritual monuments depicted in Upper Tibetan and Ladakhi rock art. The spire (’khor-lo) is segmented into thirteen layers, a standard iconographical tradition in chorten construction. The shape of this spire (squat and tapering towards the bottom and top) accurately recreates those of actual chortens constructed in Guge in the same period. The pair of prominent streamers suspended from the banner are another common feature of Tibetan carved chortens, particularly in the early centuries of the second millennium CE.

Fig. 16. A close-up of the pair of lions, ritual thunderbolt and inscription adorning the chorten carving in figure 15. Due to digital enhancement of this image, the carved lines of the chorten appear whiter than they do in real life.

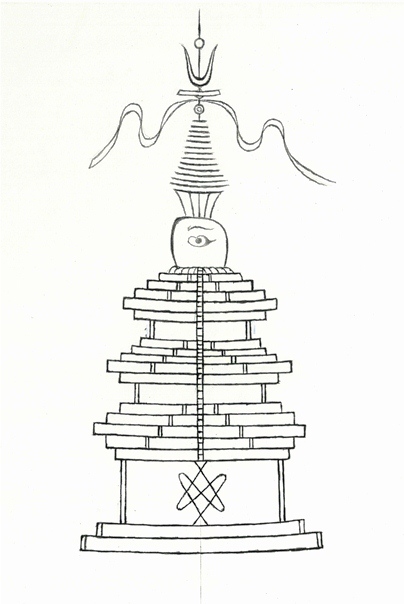

The rounded midsection (bum-pa) of this chorten is particularly small even for the design conventions of that time. In the center of this part of the chorten is an eye, presumably that of the all-seeing Buddha (ye-shes spyan). This striking feature is also found in a carved chorten near the Ladakh-Ruthok border. Spanning the multiple tiers of the lower middle part of the carving is a ladder, identifying this subject as being related to the ‘deity descent’ (lha-’babs) type chorten. Below the series of narrow tiers is a stage of the chorten adorned with a pair of addorsed lions. In between the felines is a vertically arrayed ritual thunderbolt (rdo-rje), symbol par excellence of Vajrayana Buddhism. The lions and thunderbolt, as well as the scroll work at the base of the carving, will be instantly recognizable to students of Guge art. These motifs help to place the carving in the second diffusion of Buddhism period. There is a highly worn religious inscription engraved above the lions. I did not have enough time Gyalading to decipher it, nor did I properly photograph it on account of limited film supplies.

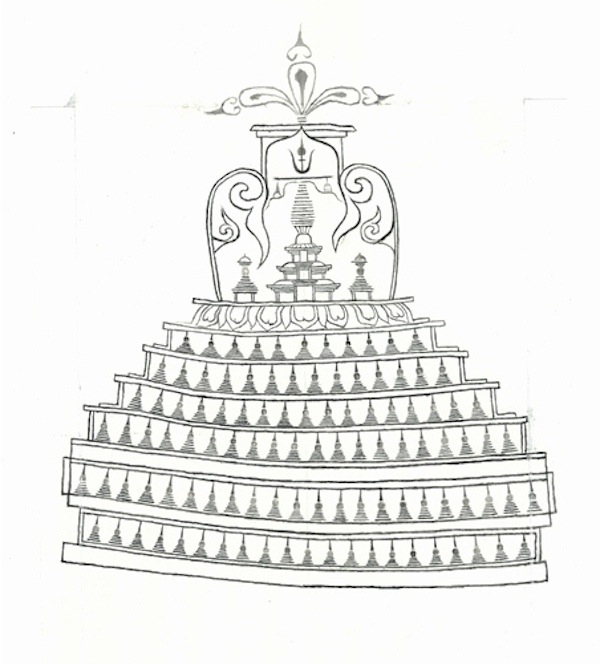

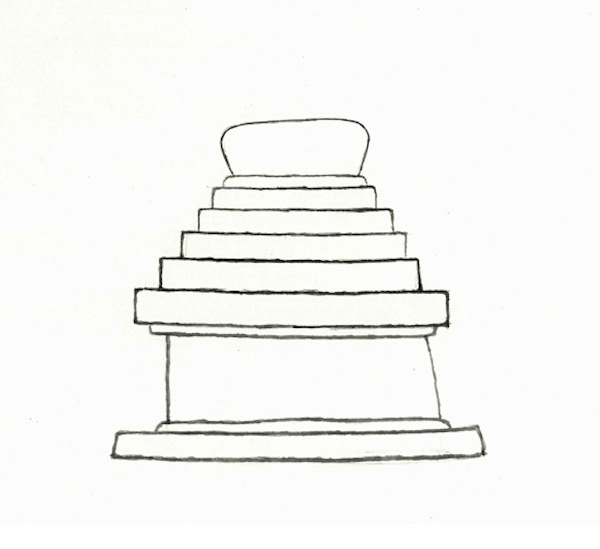

This chorten is characterized by an anomalous stepped base of of six stages, each of which is ornamented with miniature chortens. It is close in form to that in figure 14. Above the tiered base is a stage carved with lotus petals. The rather square petals are an ancient stylistic trait, which is also seen in copper alloy ornaments of even greater antiquity. The remarkable pointed midsection of the chorten boasts three subsidiary chortens of much intricacy and appeal. The scrollwork of the midsection is of a style seen in western Tibetan paintings and carvings of 11th and 12th centuries CE. There is no spire: the finial rests directly on the middle section of the chorten. I have not seen a trilobate finial like this in any other Tibetan chorten. Each lobe is crowned by an arrowhead-like motif.

It appears that the chortens we are examining were quite heavily influenced by antecedent non-Buddhist ritual structures, some of which have tricuspid finials (for more information, see February and August 2013 newsletters). One can therefore assert that this rock art was in all probability made by native artists working in a vernacular style. Nevertheless, this art ultimately owes much of its inspiration to the Buddhist chortens of northern Pakistan and Xinjiang, which began to be carved and painted on rock faces in the first half of the first millennium CE.

Fig. 19. A photograph of another carved chorten at the same site in Guge. It was only at an oblique angle that a photograph of the entire petroglyph was possible.

In form, this chorten is not unlike rock art examples dated to the early historic period (650–1000 CE). It has a base of two stages topped by a taller stage in which an abbreviated endless knot (pa-tra) has been carved. This simply rendered endless knot has open ends, a curious feature (for ancient non-standard auspicious signs, see the January 2013 newsletter). The lower portion of the chorten consists of three sets of five tiers separated from one another by a single undercut tier. In the middle of the tiny midsection is the wisdom eye and eyebrow. The truncated spire is of a type that mostly disappeared in Tibetan chorten architecture by the 13th or 14th century CE. The crescent moon motif of the finial has a horn-like appearance. Also, rather than being cradled in the crescent moon, the sun hovers quite high above it.

This intricately rendered chorten carving, with a spire, banner and final, is of the kind we have already examined. The small midsection and eye are also characteristic traits of chortens at the site. Below the midsection is a portion of the chorten designed as a three story tall temple, complete with windows and arched roofs. Such temples were actually built in Tibet, particularly in the Amdo region.

Fig. 23. A strongman (gyad-mi) in the base of the chorten carving. Above this figure is an inscription.

The elaborate base of the chorten rises up from lotus petals. In the center of the base is the carving of a strongman rendered as if he is holding up the structure. Scrollwork flanks this athletic figure. Above these carvings, in an intervening tier, is an inscription in the uchen (dbu-can) script. Unfortunately, I did not have time to work on this inscription in the field nor did I have sufficient film to carefully photograph it. I take it that it constitutes a prayer rather than a dedication but I cannot be certain.

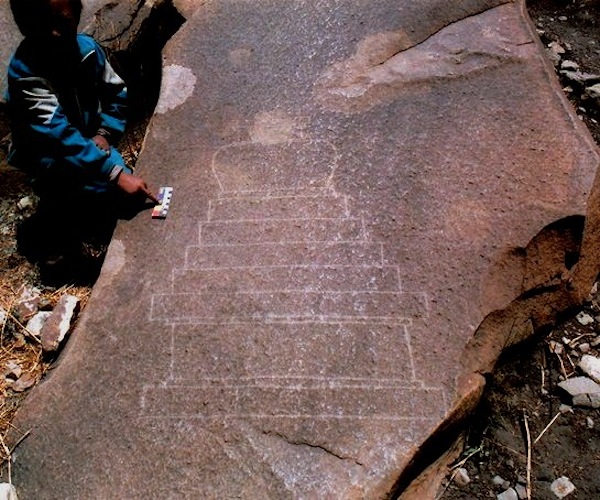

Fig. 24. A photograph of a smaller and much more rudimentary chorten on another boulder at the same site.

This sixth chorten at the same Guge site is of a kind commonly found in the rock art of Upper Tibet. Quite a few such rudimentary carvings grace the rocks of diverse locations in the region. Probably dating to the same time period as the complex carvings, the upper sections of this chorten were never completed.

Next month’s special feature: Ancient rock art in Upper Tibet up close and personal!