December 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

This month Flight of the Khyung takes you to some of the most extraordinary prehistoric art in all of Tibet. Constituting a comprehensive tableau of life more than 1500 years old, these rock carvings have never been seen in such detail. The photos posted here are so evocative that they almost speak for themselves. These were all shot this year on the Upper Tibetan Rock Art Expedition III, a mission that saw many successes.

As a supplement to last month’s article on the golden burial masks of Inner Asia and the Himalaya, there is a report in this newsletter on another example discovered in Kyrgyzstan. We also return to the golden burial mask of Malari discussed in last month’s newsletter.

I would like to call the attention of readers to an excerpt on Tibetan turquoise in the work of the eminent scholar Professor Samten G. Karmay, which now appears in the August 2013 Flight of the Khyung. It is the last article in the newsletter. I urge all those interested in Tibetan turquoise to read Samten G. Karmay’s contribution, for not only is it highly informative in its own right, it enhances an understanding of the other articles on the subject. For Professor Karmay’s work on turquoise, see:

http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/august-2013/

It is also with much pleasure I announce the publication of an article on antique turquoise by Dr. Stephen Shucart. It is found as the third feature in the August 2013 newsletter. Stephen Shucart is currently an associate professor of English at a high-tech university in northern Japan. One of his fields of research is the origin of language and the modern mind. It is the third article in the newsletter:

http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/august-2013/

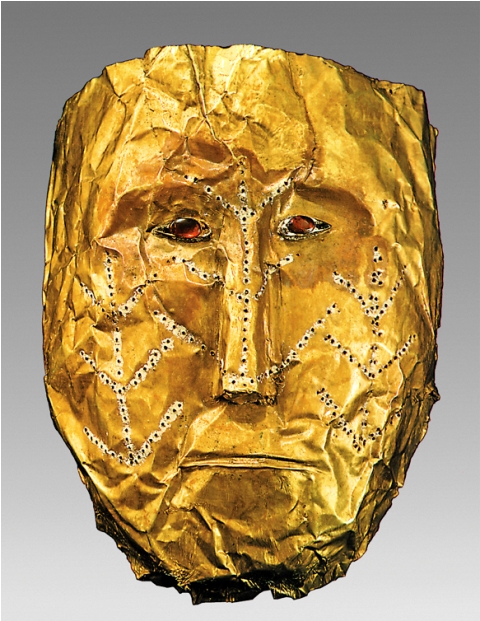

The golden burial mask of Shamsi

Fig. A. Golden funeral mask of a woman with tattoo-like decorations which represent the trees of life. These decorations were created by puncturing on the reverse and covering with white paint on the obverse. Rouran period, 5th–6th century CE. Excavated in 1958 in Shamsi, Chui Province, Kyrgyzstan. Caption and photo courtesy of Dr. Christoph Baumer. Photo credit: National Historical Museum of Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek.

The above photo and caption are taken from Christoph Baumer’s forthcoming book, History of Central Asia: The Age of the Silk Roads, vol. II. After reading about the golden masks illustrated in last month’s Flight of the Khyung, this author was so kind as to provide me with these materials from his upcoming book due out in July, 2014. I urge anyone with an interest in the history of 1st millennium CE Eurasia to obtain a copy of Dr. Baumer’s book. One will be treated to a rich panoply of cultures, religions, and art, which made the Silk Road one of the greatest chapters in Eurasian civilization.

Courtesy of the publisher, here is the synopsis for Christoph Baumer’s forthcoming book, History of Central Asia: The Age of the Silk Roads, vol. II:

The Age of the Silk Roads (circa 200 BC to circa 900 AD) shaped the course of the future. The foundation by the Han dynasty of an extensive network of interlinking trade routes, collectively known as the Silk Road, led to an explosion of cultural and commercial transactions across Central Asia that had a profound impact on civilization. In this second volume of his authoritative history of the region, Christoph Baumer explores the unique flow of goods, peoples, and ideas along the dusty tracks and wandering caravan routes that brought European and Mediterranean orbits into contact with Asia. The Silk Roads, the author shows, enabled the spread across the known world of Christianity, Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Islam, just as earlier they had caused Roman citizens to crave the exotic silk goods of the mysterious Far East. Tracing the rise and fall of empires, this richly illustrated book charts the ebb and flow of epic history: the bitter rivalry of Rome and Parthia; the lucrative mercantile empire of the Sogdians; the founding of Samarkand; the rise of Turkish Empires in today’s Mongolia; and the Chinese defeat at the Battle of Talas (751 AD) by the forces of Islam.

In style and form, the gold foil mask of Shamsi has certain features of both the Boma Cemetery specimen from northwestern Xinjiang (Ili) and those masks discovered in Tibet and the Himalaya (see last month’s Flight of the Khyung). I invite readers to make their own visual comparisons.

The Shamsi mask is embellished with three tree-like designs created by a series of perforations highlighted with a white pigment. Two of the trees cover the cheeks while the the third one was placed over the entire nose and middle of the forehead. For the sake of stimulating further discussion, I will offer an alternative interpretation of this motif. It does not seem plausible to me that the ‘tree of life’ would be used to decorate a mask for the dead. Perhaps it should instead be called something to the effect of ‘the tree of regeneration in the afterlife’. In the eastern Altai, coniferous tree trunks were found buried with their roots in some Turk funerary enclosures. The precise function of this ritual object is not known. Given the general proximity in time and space between these Turk funerary sites and the burial at Shamsi, there may be an ideological and/or functional correspondence between the motif on the golden mask and the ritual use of tree trunks. This is one avenue of inquiry worth exploring in more depth.

The archaic funerary tradition of Tibet could also offer valid points of comparison with both the trees of the Shamsi mask and those of early Turkic burials. The old Tibetan death rites were first written down circa the 8th century CE and continued to find literary expression in Bon religious texts until at least the 11th century CE. In the archaic rite, there is a ritual instrument known as the ‘head juniper’ (dbu-shug), which functioned as a vessel to enshrine and protect the the consciousness principle of the dead; it was thus referred to as the ‘soul fortress’ (bla-rdzong). The head juniper, as a kind of miraculous pillar, was employed to orient the soul of the deceased towards the celestial afterlife. Harnessing the Tibetan archaic funerary tradition as a touchstone, one might speculate that the three levels of branches on the trees of the Shamsi mask, marked the vertical stages in the passage of the soul to the otherworld.

The head juniper is mentioned in evocation rites for the soul of the deceased as part of the Bon funerary collection known as the Muchoi Tromdur. While some of the language of the Muchoi Tromdur passage given below belies Buddhist influence, the ritual itself is fundamentally archaic in character:*

In the beginning, by the sign of perfect accomplishment of the excellent gshen priests, there grew a blue turquoise juniper. Its crown of existence is sharp and hardy. Its roots penetrate the depths of the ocean. Its branches reach all four worlds. Nectar drips from each needle. At its root is the swirling nectar of consummation. At its crown the sun, moon, and stars, these three, circle around. On the branches of white copper (?) and on the conch trunk grows the fruit of perfection. When the excellent gshen were alive, this great precious juniper was a rgyang tree (instrument for securing influence over a wide area?). When the excellent gshen died it was the head juniper. Tonight, deceased dead one, please stay at this great protector head juniper. Make the head juniper, thread cross, and bird wing, these three, the support of the deceased’s body, speech, and mind.

For a detailed description of the head juniper and a comparison of Tibetan funerary practices with those of the ancient Turks, see the book Zhang Zhung, Part III, Sections 4, 6 and 9 (bibliographic data at: http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/books/).While very different cultural, ethnic, and historical forces were at play in Shamsi as compared to Tibet, the concept of a tree at the head is given expression. Perhaps in both cases these trees aided the liberation of the dead. If so, this adds to the growing body of evidence indicating the broad dispersal of material and ritualistic elements connected to funerals and burials in Inner Asia over a long period of time. In addition to golden burial masks, these widely distributed features include the erection menhirs, horse burials, horse headdresses, deposition of ephedra and sheep bones in graves, ‘animal style art’, use of effigies, application of substitute body parts on corpses, etc.

Explicit connection between Turkic and Tibetan funerary rites is made in the Dunhuang manuscript Pt 1060 (best attributed to circa the 9th century CE, pending codicological confirmation). This text indicates that Turkic regions north of Tibet shared the same tradition of horses used to ritually transport the dead to the next world. In this text, 12 lineages of psychopomp horses are located in Tibet while a 13th is attributed to Drugu. Drugu seems to refer to the Uighurs, but it could possibly also denote an earlier period in the ethnohistory of the Tarim Basin. In Pt 1060, the gods (Yol, Reg-rgyal hir-kin and Dan-kan) and one of the funerary horses (Hol-tsun) have names of decidedly Turkic origins. The historical placement of this literary reference is not very clear. It likely refers to the period of Tibetan imperial conquest (mid-7th to mid-9th century CE). However, the usage of genealogical terms in the text to denote the male and female sources of lineages (cho and ’brang) may indicate that the psychopomp horses are being enumerated within a deeper historical context.

Did Turkic groups actually have such psychopomp horses, or is the Pt 1060 account merely based on a pretension of Tibetan imperial might? That the Turks and Tibetans did indeed share certain conceptual and procedural structures related to the funeral and afterlife is given credence by some of the archaeological evidence outlined above. While further inquiry into the historical and archaeological dimensions of the horses of Drugu in Pt 1060 is called for, this text does provide us with an intriguing link, hinting at the widespread diffusion of funerary ritual and eschatological traditions in Inner Asia.

For the Pt 1060 reference discussed above, see Zhang Zhung, pp. 522–524.

I was also able to share a pre-publication version of the above article with another colleague of ours, Sören Stark, Professor of Central Asian Art and Archaeology at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University. He was kind enough to furnish us with additional comments and observations concerning the burial masks of north Inner Asia and further afield germane to our exploration of the subject. What Professor Sören Stark has written follows next.

An overview of golden masks from Inner Asia: A contribution by Sören Stark

The whole burial complex at Shamsi is discussed by Kožomberdieva, Kožomberdiev, and Kožemjakov (1998). Another example of a golden funerary mask comes from a rich burial at the cemetery of Dzhalpak-dëbë in present-day Kyrgyzstan, dated to the 4th or 5th century CE. (Каниметов et al. 1983, p. 41). For ‘Migration period’ (4-5th century CE) Eurasia a useful (though not exhaustive) overview of the phenomenon of funeral masks during the 4th and 5th centuries CE in Eurasia is given by Benkő (1992-1993). Of course solid metal masks are probably only the preserved ‘tip of the iceberg’ of what once existed, including face-covers made of perishable materials: see the cover made of a hemp fiber mass worn by the famous 4th or 5th century CE burial from Yingpan, or face covers made of precious silks onto which metal appliqués were sewn (for one such appliqué type, which can be traced from Inner Mongolia to Hungary see Stark 2009). We should also not forget the often splendidly painted clay masks from the Tashtyk culture in present-day Khakassia in Southern Siberia, dating roughly to the same period (Вадецкая 2009). And also from further west, i.e. from the northern Black Sea area, golden funerary masks dating to the 2nd-3rd centuries CE have been found (Бутягин 2009). Note also that the kidney-shaped garnet (or almandine?) inlays on the famous Boma mask mentioned above most likely originate from a workshop in Eastern Europe or the Mediterranean, as recently pointed out by A. Koch (Koch 2008). See my review of this article (Stark 2010).

Literature mentioned Benkő, M. 1992-1993. “Burial Masks of Eurasian Mounted Nomad Peoples in the Migration Period” in Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae vol. 46, pp. 113–131.

Koch, A. 2008. “Boma – ein reiternomadisch-hunnischer Fundkomplex in Nordwestchina,” in Hunnen zwischen Asien und Europa. Aktuelle Forschungen zur Archäologie und Kultur der Hunnen, Beiträge zur Ur- und Frühgeschichte Mitteleuropas. Edited by Historisches Museum der Pfalz, Speyer, pp. 57-71. Langenweissbach: Beier & Beran.

Kožomberdieva, E. I., I. V. Kožomberdiev, and P. N. Kožemjakov. 1998. “Ein Katakombengrab aus der Schlucht Šamsi,” Eurasia Antiqua 4: pp. 451-471. ___Stark, S. 2009. “Central and Inner Asian Parallels to a Find from Kunszentmiklos-Babony (Kunbabony): Some Thoughts on the Early Avar Headdress,” Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 15: pp. 287-305. ___2010. “Review of”Historisches Museum der Pfalz Speyer (Ed.): Hunnen zwischen Asien und Europa. Aktuelle Forschungen zur Archäologie und Kultur der Hunnen,” Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 5: pp. 201-208. Бутягин, А. М. Editor. 2009. Тайна золотой маски. Каталог выставки. Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Государственного Эрмитажа. Каниметов, А., Б. И. Маршак, В. М. Плоских, and Я. А. Шер. Editors. 1983. Памятники культуры и искусства Киргизии. Древность и средневековье. Ленинград.

More on the golden mask from Malari

Thanks to the kind regard of Professor R. C. Bhatt of Garwhal University, I now have a copy of the preliminary archaeological report made concerning cut chamber burials in Malari, which was published in Japan:

Bhatt, R. C.; Kvamme, K. L.; Nautiyal, V.; Nautiyal, K. P.; Juyal, S.; Nautiyal, S. C. 2008-2009. “Archaeological and Geophysical Investigations of the High Mountain Cave Burials in the Uttarakhand Himalaya” in Indo-Kōko-Kenkyū – Studies in South Asian Art and Archaeology, vol. 30, pp. 1–16.

I will now provide a synopsis of materials in this paper pertinent to the golden mask of Malari. In 1986 and 1987, Professor R. C. Bhatt conducted archaeological work in the Garwhal Himalaya in order to excavate and better understand the cultural background of an intact cave burial in Malari. Cut from calcareous rock on a hillside, this burial chamber is 2.4 m deep. Its mouth was sealed by a boulder. The chamber contained grave goods as well as the complete skeleton of what is identified as a yak hybrid (zoba, mdzo-ba). Additionally, some bones of the dog, sheep, and goat were interred (however, no human remains were detected). Based on a recent analysis of animal skeletal remains, iron and bone artifacts, and glazed pottery from the site, this burial and another of its kind in Malari have been dated to circa 1st century BCE. Among the large quantity of ceramics entombed were intact vessels comprised of dishes, spouted pots, and jars of red and black polished ware, some of which are decorated with incised geometric designs filled in with a white pigment. A variety of trihedral iron arrowheads and spear points were recovered. Also, iron nails inserted into oak twigs and a bronze bowl with a diameter of 16 cm were found. The most remarkable discovery was a mask made of beaten gold weighing 5.23 grams (for photograph, see last month’s Flight of the Khyung).

In 2001, a similarly sized and constructed burial chamber was discovered in Malari by R. C. Bhatt and colleagues. This burial yielded a complete human skeleton with the head pointing southwest and the feet oriented towards the northeast. A preliminary osteological study indicates that this was the skeleton of a juvenile between 12 and 15 years of age. Among the ceramics were 11 intact vessels red and gray in color, some with incised geometric designs. The most distinctive of these are red-ware vessels with wide, slightly flaring mouths, bulbous bottoms, single lug handles, and long spouts supported by a bridge connecting it to the rim of the pots. One of these pots has a conical pedestal.

Bhatt et al. 2009 consider the burials of Malari in the wider cultural and geographic context of western Tibet and Mustang, noting that cave burials are found in these other regions as well. As regards the yak hybrid burial, the authors write, “Taking into consideration the immense usefulness of the animal, it must have been treated as a member of the family, and therefore it was given a proper burial as a mark of respect as evident from the nature of the burial.” It is reported that one AMS assay of an unspecified bone sample from the cave burials was carried out and yielded a date of circa 100 BCE. The authors note that burials at Mebrak (Mustang valley) and Kharpo (Guge) fall within this general time frame. The authors are inclined to group these burials together, in the sense that they demonstrate “a common cultural trait”. The authors elaborate, stating that these regions “must have shared many common practices and beliefs”.

Using techniques based on magnetic gradiometry and electrical resistivity, Bhatt et al. 2009 have identified several other sites in Malari that probably conceal burial chambers.

My comments

It would be helpful if more organic remains from the two excavated burial chambers of Malari were subjected to chronometric testing. The results would help fix the date of the burial, corroborating results from just one sample that was AMS assayed (the details of which have not been published in Bhatt et al. 2009). A formal study of the ceramics recovered would also be very useful. Of course a number of other kinds of analyses (of a stratigraphic, cultural, and molecular nature) of the bones and grave goods could also be carried out to good effect.

In addition to the presence of the golden mask, the ceramics finds from Malari are directly comparable with those recently unearthed at Gurgyam by Chinese archaeologists. See the round bottom pot with single lug handle and wide flared mouth in October 2010 Flight of the Khyung (fig. 15) and fig. 11 in Bhatt et al. 2009. The general similarities in form between two vessels notwithstanding, there are important typological differences between them (shape of the bottom, width and flare of neck, etc.). More important to a comparative analysis is the method of manufacture, fabric and surface finish of the two vessels. This kind of detailed information is not provided in Bhatt et al. 2009, nor yet by the Chinese. Moreover, little can be discerned from the small b&w photo in in Bhatt et al. Anyhow, there is an even more striking parallel in the ceramic assemblages of Malari and Guge: the existence of similarly made red-ware pots with round bodies, wide flaring mouths and long spouts. See figs. 8 and 9 in Bhatt et al. The Chinese example excavated in 2013 has not yet been published; however, thanks to my Chinese colleagues I was able to see the Gurgyam example. The Gurgyam pot is closest in form to the vessel on the right side of fig. 9, sans the conical pedestal, but with the same type of arched bridge connecting the spout to the body of the vessel (the Gurgyam bridge is decorated with three incised circles or eyes extending across its length). The other two spouted vessels from Malari are also close in form but the neck bridges were made with a double curve.

Hopefully the Indian and Chinese archaeologists will furnish us with more serious studies of ceramic finds in adjoining Himalayan regions than what we have to date. Typological and fabric analysis based on modern archaeological methods is sorely called for if we are to achieve a better understanding of the cultural and technological elements involved. It is essential that standard scientific techniques such as thermoluminescence (TL) dating, X-ray radiography, X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and neutron activation analysis (NAA) are brought to bear on the study of the structure and composition of the ceramics discovered in Guge and Malari. It is only by undertaking these lines of inquiry that the method of firing, mineralogical composition of the clay and ceramic petrology (among other empirical parameters) can be known.

Despite the infancy of our field of study, some preliminary observations are in order. The masks and ceramic vessels underline a cultural relationship between Guge and Malari in the 100 BCE to 400 CE time frame. These two regions possessed similar technological skills (also encompassing iron implements and bronzeware) applied to the world of funerary rites and burial. My hunch is that the ceramics of Malari and Gurgyam were produced locally, as they exhibit significant differences as well as similarities. It is also inherently difficult to transport large numbers of ceramics over the Himalaya. As noted in last month’s newsletter, the evidence generally indicates that these regions shared certain cultural customs and traditions in common.

As for the burial of a yak hybrid in Malari, this is liable to be a constituent part of funerary rites carried out for the dead. The Dunhuang text Pt 1068 furnishes a fairly extensive account of the origins of the yak hybrid used to transport deceased women to the afterlife (see Zhang Zhung, pp. 538–542). In this colorful origins tale, composed circa the 9th century CE, a hybrid yak named Dzomo Drangma (Mdzo-mo drang-ma) is appointed by the funerary priest Durshen Mada (Dur-gshen rma-da) to assist a young girl who died under the most wretched of circumstances. Although this tale is explicitly set in “ancient times”, one should not conflate the older Malari burial with the contents of the text; significant ideological differences in these burial rites may possibly be indicated. Nevertheless, the custom of employing a yak hybrid as a funerary appliance extends to both spheres, strongly suggesting a Tibetic cultural orientation for the Malari burial.

The Malari and Chuthak golden masks are supposedly around 2000 or 2100 years old. If those dates hold up to further scrutiny, they suggest that these masks of sophisticated manufacture predate the cruder Samdzong and Gurgyam examples by three to five centuries (for descriptions and images of these masks, see last month’s newsletter). Continuing in this vein, it may be that the tradition of Himalayan and Tibetan golden burial masks was in decline by the 3rd to 5th centuries CE. In addition to cultural and technological transmissions from the west that appear to have informed the creation of the Shamsi and Boma masks touched upon by Sören Stark in the above article, provided the dates for the Malari and Chuthak masks are confirmed, it is worth pondering that a vector of cultural and artistic influence coming from Tibet and the Himalaya may also have had an impact on the development of north Inner Asian burial masks (one possible carrier northward from the Plateau were the Huns). Furthermore, the provisional chronology for the Malari and Chuthak masks could possibly be indicative of an earlier (Iron Age) Eurasian diffusion of golden burial masks, which also encompassed those of ancient Illyria, Thrace, and Greece. Enough of that now. I think readers will see there are many intriguing angles on the ancient burials of western Tibet and the Himalaya to explore in the years ahead.

Finally, it is worth mentioning Tibetan miniature copper alloy masks classed as thokcha (thog-lcags). The faces represented on this very rare group of artifacts are somewhat different in form from the golden burial masks but probably of comparable age. The thokcha masks appear to be talismanic in function but they may have had other uses as well, such as receptacles (rten) for personal protective spirits. For an image of one of these miniature masks, see the July 2010 Flight of the Khyung.

Hunters, Warriors, Shamans and Lovers: Chronicles of ancient life at Thakhampa Ri – Part I

Introduction to Thakhampa Ri

Since 1995, I have surveyed more than 70 sites with rock art in the vast plains and mountain ranges of uppermost Tibet. The thousands of rock paintings and carvings documented represent many spheres of ancient life in the region from possibly as early as 1500 BCE to the first centuries of the second millennium CE. There is much captivating rock art to choose from; however, few rock canvases are as dramatic as Thakhampa Ri (Mtha’ kham-pa ri), situated in the northwestern Tibetan district of Ruthok (Ru-thog).

On just one small outcrop at Thakhampa Ri, there is a surprisingly wide spectrum of rock carvings portraying ancient life in rich detail. This record for posterity encompasses many aspects of the culture, economics, and society that existed before the appearance of Buddhism and the written word in Tibet. No other rock art site in Upper Tibet offers such a selection of subjects, compositions, and themes concentrated in one tiny area as does Thakhampa Ri. On a series of interconnected rock panels there are petroglyphs of hunters, herders, travelers, priests or shamans, probable deities and spirits, combatants, and couples. Clearly, carvers at Thakhampa Ri were intent on showcasing their customs and traditions, revealing to whomever might see their work the activities and aspirations they held dear.

The rock art of Thakhampa Ri was first made known to the world by the Tibetan archaeologist Sonam Wangdu. He and his colleagues visited this remote site in the early 1990s. In 1994, Sonam Wangdu brought out his landmark work, Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings (trilingual introduction by Li Yongxian and Huo Wei), published in Chengdu by the Sichuan People’s Publishing House. This lavishly illustrated book features the rock art of 22 different sites in Upper Tibet. With the exception of the many caves of Tashi Do (Bkra-shis do), no place receives more extensive treatment in this book than Thakhampa Ri. Sonam Wangdu, an archaeologist with a keen appreciation for Tibetan history and culture, was well aware of the importance of this rock art theatre for the study of early Tibetan civilization (I had the pleasure of first meeting Sonam in the early 1990s).

Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings devotes 14 pages to the rock art of Thakhampa Ri. In this book there are 21 high quality color plates illustrating its petroglyphs. Sonam Wangdu aptly describes the art of Thakhampa Ri as “rich and varied”, while in Tibetan he writes that it is “exceedingly complete and sublime” (Ha-cang phun-gsum tshogs-pa yod; p. 80). The Tibetan language here employed may seem flowery, but, as I think you shall see, Thakhampa Ri deserves much recognition.

When Sonam Wangdu and his team surveyed Thakhampa Ri in the 1990s, digital photography had still not been perfected. As I know from my own experiences in the region in that period, one tended to ration the amount of photos taken at each archaeological site, for only so much film could be carried. Being constrained like this limited the visual coverage of art and monuments to a greater or lesser extent. Now with digital photography, it is possible to lavish an almost unlimited number of photographs on anything of interest. With this capability in hand, this year I endeavored to capture every single subject etched on the outcrop at Thakhampa Ri.

Geographic, cultural and chronological characteristics of Thakhampa Ri

Thakhampa Ri (4735 m) is situated in a major tributary valley of the Domar Chu (Rdo-dmar chu), a river that debouches into the large freshwater lake known as Tshomo Ngangla Ringmo (Mtsho-mo ngang-la ring-mo) 50 km downstream of the rock art site. The mountains that rise above Thakhampa Ri to a height of more than 6000 m constitute the extreme eastern extent of the Karakorum Range. Marco Polo sheep still grace the flanks of these mountains. This region of Tibet (western Ruthok) is extremely arid and very sparsely populated.

Fig. 1. The mountain of Thakhampa Ri. The rock art site is the dark pyramidal outcrop near the base of the mountain (middle of photograph).

Thakhampa Ri is one of four rock art sites in different side valleys of the same locale. These sites are situated near the mouth of the valleys and all have a southern exposure. Perennial sources of water are scarce in the area. This limits contemporary occupation to the late Spring when water is available through the melting of snow from the surrounding mountains. I am told by local residents that in particularly dry years, when there is little snowmelt, herders (’brog-pa) are unable to graze their animals in the valleys of rock art.

While there may have been significantly more water in ancient times, there is little visible evidence that large streams ever ran past the rock-art sites year round. Thus, like today, Thakhampa Ri may have been occupied on a seasonal basis by highly mobile groups of hunters and pastoralists. Moreover, there is no evidence for large-scale sedentary settlement near the four rock art sites of the locale.

Thakhampa Ri and its sister rock art sites are all conspicuously placed at the edge of valleys, on the largest and most appropriate rock outcrops. This seems to indicate that they were made with maximum visibility in mind. The reddish, bluish, and brownish metamorphosed sedimentary rocks (?) furnish fine-grained and fairly uniform surfaces, which are ideal for carving. With its southern exposure, Thakhampa Ri can warm significantly in bright sunshine, having made it a relatively comfortable place to tarry for the creators of the rock art. Perhaps Thakhampa Ri and the other three sites in the area are where the ancients made their camps. In any case, these locations are now used by pastoralists for their encampments, and in recent years a few huts and corrals have come up.

The functions of rock in general, while a matter of scholarly debate, appear to have been very wide. Thakhampa Ri may have served a variety of purposes, all of which remain rather hypothetical. Possible functions for this site include open-air sanctuary or place of worship, collective narrative record or mythic reenactment, advertisement of historical or contemporaneous exploits of a particular social group, and instrument to ensure social and ecological well being. These various functions need not have been mutually exclusive and may have been combined in any manner of still unknown ways.

The content of rock art at Thakhampa Ri is of a familiar Upper Tibetan cast. The subjects, motifs, and themes there reverberate throughout the greater region. The hunting of wild yaks and other large wild ungulates with bows and arrows ties Thakhampa Ri to rock art at many sites in the region. Other subjects represented in Thakhampa Ri with a wide geographic distribution include riders of wild ungulates, duelers, anthropomorphs with rayed or feathered headdresses, and carnivores pursuing prey. Furthermore, the styles of rock art at Thakhampa Ri are repeated at other places in Upper Tibet. The bold and robust depiction of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures is a hallmark of this region. Common motifs include wedge-shaped tails and prominent belly fringes on wild yaks, ornithic features added to human figures, etc. More specifically, wild ungulates ornamented with a scroll or S-motif find much currency in the rock art of Ruthok. The selection of animals for depiction (wild yaks, deer, wild caprids, raptors, equids, etc.) at Thakhampa Ri and other sites in Upper Tibet reflect a common high elevation environment in which similar economic strategies were pursued.

The thematic and stylistic commonalties of Thakhampa Ri and other sites in Upper Tibet indicate that it was created by a people with analogous cultural traits. That is not to say the ancient population of Upper Tibet shared the exact same language, ethnicity, and cultural traditions, for, like today, there may have been notable sub-regional variations. Yet, when the rock art record is viewed in tandem with the ancient monumental record, a surprisingly high degree of homogeneity is observed. This permits us to speak of an Upper Tibetan culture, extending west from the 89th meridian to the borders of Ladakh and probably beyond, which existed prior to the 7th century CE. Rather than a monolithic entity, however, this ‘paleoculture’ had its own dynamic and diversity. This is borne out by content unique to Thakhampa Ri and by well-known motifs and subjects rendered there in novel ways.

One of the most intriguing characteristics of Thakhampa Ri is the lack of the swastika, a symbol portrayed at most rock art sites in Upper Tibet. The swastika is far less common in the rock art of Ladakh, and perhaps its absence at Thakhampa Ri has to do with its proximity to that region.* As is well known, cultures ebb and flow over time, and the merging and divergence of traditions and customs marks human activity more generally.

For more information on the rock art of the western portion of the Tibetan plateau, see Bruneau and Bellezza, 2013. “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ in Revue d’etudes tibétaines vol. 28, pp. 5–163.The dating of rock art at Thakhampa Ri cannot yet be determined with any degree of precision. We can hope that scientific breakthroughs will soon occur to permit the chronological observations made here to be objectively tested. The presence of the riding horse serves as a terminus a quo for most or all rock art at Thakhampa Ri. This indicates that the carvings are no older than the early or developed Iron Age, circa 800–100 BCE. Most of the petroglyphs, however, seem to be more recent, dating to the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). This is suggested by the main technique of carving, the light bruising or pecking of the stone surface. The style of art is also suggestive of the protohistoric period (somewhat stilted execution of figures, rigid postures assumed by animals, etc.). To these technical and stylistic criteria can be added the generally moderate levels of re-patination of the petroglyphs: very few specimens have the dark, advanced patina associated with more ancient periods of rock art in Upper Tibet. Nor are Bronze Age / Iron Age motifs such as so-called mascoids and chariots represented at Thakhampa Ri.

All factors considered, I am inclined to date the bulk of rock art at Thakhampa Ri to the first half of the first millennium CE. As there is only one true palimpsest, a limited repertoire of styles, and quite uniform physical wear of carvings, the bulk of rock art at the site was probably made in a relatively narrow band of time within this period. While suitable space for the carvings was at a premium, there are few overruns of compositions upon others. This also suggests that the site was not used for a great deal of time. Nevertheless, a multiple of carvers were at work at Thakhampa Ri. This can be seen in the variable execution of the petroglyphs and in the wide spectrum of subjects and themes.

A catalogue of rock art images from Thakhampa Ri

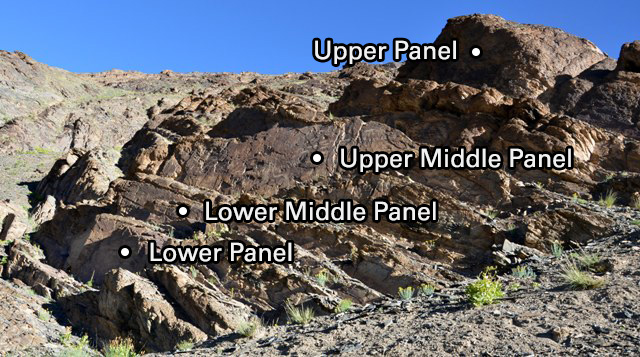

Fig. 2. The central outcrop of Thakhampa Ri. The four panels of the main site are designated.

The petroglyphs of Thakhampa Ri are found on ten major naturally occurring rock panels, which are oriented vertically or are slightly off the vertical plane. The center of the site consists of four panels that form tiers in the outcrop. I call the largest and most important panel the ‘main panel’ or ‘upper middle panel’ at the center of the site.

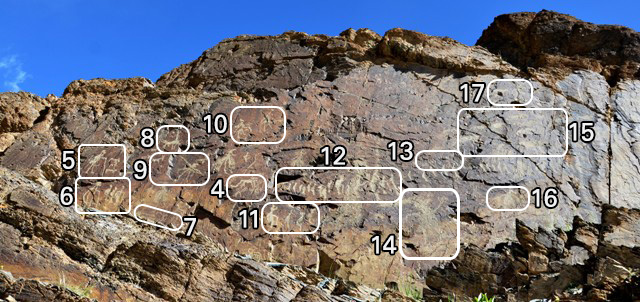

Fig. 3. The main rock art panel at Thakhampa Ri (6.3 m x 2.1 m). Sonam Wangdu (1994: 84) gives the dimensions of this panel as 6.2 m x 2.9 m, as he includes the lowermost uncarved portion. The eastern ¼ of the main panel is not shown. It extends beyond the right side of the photograph. The locations of rock art selected for individual depiction in this work are designated.

This month’s newsletter focuses only on the main (upper middle) panel of Thakhampa Ri. Thirty images of small sections of this panel or of individual compositions will be examined below. Both the most representative and the most dramatic petroglyphs have been chosen for illustration, giving readers an encompassing view of this art. In next month’s Flight of the Khyung, an additional 29 images from other panels will be featured. By accessing both this and the January 2014 newsletter readers will secure full visual and interpretive treatment of Thakhampa Ri.

Writing about Thakhampa Ri, Li Yongxian and Huo Wei, in the introduction to Sonam Wangdu’s book (1994: 30), state, “…for instance, the marching of a contingent, dancing, fighting, hunting, and worshiping of deities inseparably coexist in one painting”. Indeed, the most salient quality of the contents of Thakhampa Ri is its comprehensive scope. Many, if not all, major spheres of ancient life, as perceived by the carvers themselves, are delineated. Thus, we find hunting and pastoral scenes portraying economic dimensions of ancient life as well as the cultural and material characteristics of these activities. There are a number of renderings of wild ungulates in a solitary aspect or in a herd. Such animal portraits are a distinguishing characteristic of rock art in Upper Tibet. These compositions may have had a wide purview of meaning and function. Having speculated on this subject before, I will not rehash my ideas here.*

For example, see my book Zhang Zhung, pp. 171–175.There is a range of anthropomorphic figures in special attitudes and costumes at Thakhampa Ri. What might be priests, shamans, deities or spirits, many of which have zoomorphic traits, are depicted. The spectacular appearance and dress of some kinds of figures stand out from more prosaic looking hunters on horseback or long lines of ‘backpackers’ at the site. This underscores the special identity, be it mythic, ceremonial, or divine, of those anthropomorphs (humanoids) with fantastic or exalted guises.

As I have noted repeatedly in my writings, it is not possible with certainty to identify rock art figures with specific characters from Tibetan literature. Rock art and literature are two very different types of records, making verification of any correlations drawn very difficult except in the most general of terms. Deities, ancestral personalities, ritualists, bards, mythic heroes, nobility, etc. may all be among those portrayed at Thakhampa Ri, as they are in Tibetan texts.

At Thakhampa Ri there are a number of compositions showing combatants in battle or contenders in what appear to be martial contests. Here again an element of the mythic or divine may be at play but we have no reliable means at our disposal for distinguishing what was intended as a mundane composition from ones with supernatural dimensions. Likewise with male-female couples: we do know if these were literal depictions of a carvers conjugal life, or if they had wider symbolic, narrative, or historical significance.

The most common subject at Thakhampa Ri is the ambulatory human figure, most or all of which carry something on their backs. Some also grasp walking sticks or staffs. There is a more-or-less continuous line of about 60 of these figures stretching from west to east on the main panel. There are also several shorter lines, with just three to five figures in each. These figures are generally depicted moving in an easterly direction. They walk in single file. On the east portion of the main panel a meandering line seems to represent the path trodden. Other lines of similar figures are found on the lower panel. The historical and functional dimensions of these compositions were lost long ago with their makers and users. It might be speculated that they depict parties traveling in the very terrain they overlook, perhaps heading to or from seasonal hunting grounds (if they were herders they should be shown with their livestock). Similarly, Sonam Wangdu (1994: 86) interpreted the long lines of figures as travelers carrying baggage on their backs. Nonetheless, entirely different interpretations of the journey portrayed can also be entertained.

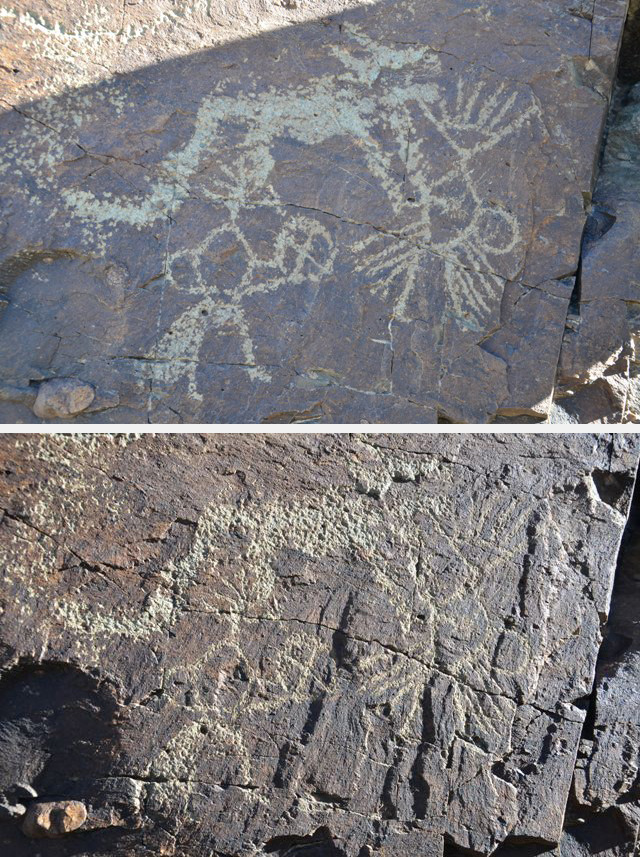

Fig. 4. Here depicted are two photos of the same rock art composition, one shot in direct sunlight and one in the shade. See Sonam Wangdu (1994: 89) for a similar contrast in imaging.

In direct sunlight, the various incisions and abrasions of rock carvings have a well-defined quality. Also, photos made in sunshine furnish an accurate picture of the re-patination of petroglyphs, because colors tend to be a close approximation of those on the actual rock surface. Photos taken in the shade supply a more strongly graphic portrayal of a carving, endowing it with the quality of a drawing or tracing. In the shaded image, all salient features of a petroglyph are immediately evident. Yet, carved lines photographed in the shade give the effect of being somewhat indistinct due to the way in which light is polarized. Also, images in the shade are more bluish in color because the molecules of the atmosphere scatter blue light more effectively. A certain ‘bleaching’ effect also occurs in the shade, with rock carvings appearing lighter in color than they really are.

In this article, I have relied more heavily on shaded images in order to highlight the actual form of compositions. As for photographs shot in the sunlight, adjustments to the camera settings notwithstanding, results are chiefly dependent on the angle and the intensity of sunlight striking rock art. Sunlight hitting rock surfaces at highly oblique angles (such as can occur near sunrise and sunset) tends to obscure rock art, while the sun very high in the midday sky produces much glare and reflection. Sometimes diffuse sunlight (as through a thin layer of clouds) is best for capturing rock art. This is especially true in high elevation Upper Tibet, where the sun’s radiance is extremely strong.

Fig. 4 depicts two anthropomorphous figures with avian traits (each approximately 15 cm in height). The figure on the left has a triangular, beak-like proboscis, lines on the top of the head resembling feathers, and what appears to be a tail or a skirt, which is also bird-like in quality. This egg-shaped figure holds a round object divided into four quarters. The placement of its arms is congruent with the beating of a drum. The figure on the right has a triangular head and what appears to be feathers on its head and below the waist. A round object, probably a drum, is by its side. A long-tailed carnivore with erect ears slightly obscures the pair of anthropomorphs. According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 83), this figure is a wolf. It is also possible that it is rather a tiger or other felid.

Sonam Wangdu (1994: 83) provisionally identifies the pair of anthropomorphs as “wizards” in English and as “spirit-mediums” (lha-pa) in Tibetan, and likewise describes them as being ornamented with feathers (bya-sgros brgyan-pa). I concur with Sonam Wangdu’s general comments on the identity of this composition. There are numerous textual references, especially in the Bon religion, to support these observations. The drum is recorded as one of the prime instruments of priests (bon and gshen) in primal and ancient times. The erecting of eagle and vulture feathers on the head and the wearing of robes (thul-pa) made from these materials are also sacerdotal elements well attested in Bon literature. Whether or not these priests went into trance cannot be established with certainty from the available literary, ethnographic, and archaeological evidence, but indications are that they probably did.

For information on priestly traditions in ancient Tibet, please refer to my various print works and those of Professors Samten Karmay and Namkhai Norbu.

Thus, it appears that sacred traditions documented in Tibetan literature find confirmation in the rock art record, the written sources preserving historical information, and lore from protohistoric, and even more distant, times. Although this is reasonable assumption, a number of admonitions must be made. First of all, written accounts from the historic era perceive the past through the lens of their own times and exigencies, potentially altering or distorting what came before. Secondly, by its very nature, rock art conveys ambiguous signals to those who now examine it. What may seem like a priest or wizard to us may have been intended as a divine, mythic, or ancestral personality. The iconography of all these types of beings are closely related in Tibetan literature, further complicating any assignment of function to rock art. Thirdly, it is crucial that one is not misled by the broader religious and cultural context of Tibetan literature, assigning its motivations and sensibilities to rock art that is far more ancient. With these cautions in mind, the ancient artistic legacies of Tibet can be explored through literature with much fruitfulness, even if most things remain in the realm of uncertainty.

Fig. 5. An anthropomorph (40 cm tall) in profile, with what appears to be a backpack and walking stick, following three animals.

This is an important rock art composition because it seems to depict a herder with his flock. Pastoral scenes in the rock art of Upper Tibet are rare. Sonam Wangdu (1994: 83) identifies the three animals as goats. However, the lowermost figure has the form of a yak and the middle figure could possibly be a sheep. If this identification is correct, the rock carving portrays the three most important species of livestock in Upper Tibet. The anthropomorph sports a long object extending out from its waist. This appears to be an implement, ornament, item of clothing, or possibly a penis. If this is in fact the male sex organ, this composition may have had fertility connotations.

Fig. 6. Four figures that appear to be walking, two of which probably carry walking sticks.

These anthropomorphs all seem to have backpacks. The large figure rendered in outline on the left, by virtue of its relative size (38 cm tall), may have been envisioned as being qualitatively different from its companions. In several other lines of figures at Thakhampa Ri one such ‘giant’ is planted. A divine guardian or mascot of travelers is one possible identity for these larger anthropomorphs. The big figure in Fig. 6 is portrayed with a phallic or mace-like object at the waist.

Fig. 7. An archer mounted on horseback in pursuit of a wild yak (the two figures combined have a length of 60 cm). This is a typical Upper Tibetan hunting scene depicting the final kill. Note the recurve bow of the hunter and what seems to be the male sexual organ of the yak.

Fig. 8. A curious scene depicting an anthropomorphic figure with an animal-like head, arms outstretched, sitting or standing on a yak (27 cm in height).

To the left of the theriomorphic figure is another anthropomorph with spread arms and a beak-like extension on the head. The form of this figure gives the impression that it is flying. Below it is an ungulate that appears to be following the yak. The etching technique employed to create the two animals and rider and the analogous level of re-patination exhibited suggest that this is an integral composition.* On the other hand, the hovering figure was carved with a lighter touch. The colorful appearance and aspect of the two anthropomorphs suggest may suggest that they have supernatural identities.

For other figures mounted on wild ungulates, see the July 2012 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 9. An anthropomorphic figure with a long object slung over its shoulder (20 cm tall excluding the long object).

This figure has a line extending upward from the right side of the middle of the body (phallus?). An animal (yak?) is directly above the anthropomorph. To the right is an animal resembling a billy goat, but it cannot be determined if this is a wild or domestic version of a caprid. This animal is situated just below the small ungulate in Fig. 8.

Fig. 10. Two anthropomorphs that may be ithyphallic in nature (figure on left 20 cm tall).

These figures seem to carry something on their backs and the one on the left may be wielding a bow and arrow. The triangular head of the specimen on the left is bird-like. Birds and bird-men rock art is widely distributed in Upper Tibet, reflecting the mytho-ritualistic importance of birds in accounts of early times in Tibetan literature.

If indeed the male sex organ is commonly depicted at Thakhampa Ri, it suggests a strong preoccupation with virility. In the very high altitude environment of Upper Tibet, there are powerful physiological constraints acting upon human fertility. Ithyphallic representations may have possibly demonstrated male sexual potency as a means to counteract limitations to reproduction occurring in harsh physical conditions.

Fig. 11. A line of four anthropomorphous figures (figure on left approximately 30 cm tall).

Subtle differences in re-patination and etching techniques may indicate that different hands were responsible for their creation. The large figure on the left has a long, hooked muzzle reminiscent of a theriomorphic head. Perhaps it was envisioned as some kind of guardian or escort for the travelers. The next figure to the right possibly has an ornithic head or mask. Archaic and Lamaist deities quite often have animal heads and other zoomorphic attributes grafted onto human bodies.

Fig. 12. Fourteen figures in the long row of ‘travelers’ on the main panel, two of which appear to carry walking sticks. These anthropomorphs are up to 35 cm in height. Most appear to be hauling packs on their backs. Each figure is rendered differently, as if real personalities were represented in this composition.

Fig. 13. What appears to be two wild asses (rkyang) depicted above the long line of hikers (each is approximately 15 cm long).

The prominent upright ears and broad heads of these creatures are prominent anatomical traits of the wild ass. Also, the markings on the body simulate the variegated color of the wild ass, a common ungulate in Upper Tibet. These equids are situated just to the right of the figures depicted in Fig. 12.

Fig. 14. A nebulous anthropomorph etched just below the carvings in Fig. 12 (50 cm tall).

This figure appears to be dancing, shamanizing, or engaged in some other ritualized activity. In its left hand is a roundish object, which perhaps represents a drum (seemingly, a very common attribute at Thakhampa Ri). If this composition is depicted in profile, it appears to have the snout of an animal. The large extension on top of the head maybe part of a headdress.

Fig. 15. This part of the main panel includes the middle section of the long line of ambulatory figures.

The row of backpackers appears to be on a steep path rendered by a carved line below their feet. This line seems to have been created before the travelers themselves were carved. Above the line of anthropomorphs, a horseman (52 cm in length) pursues one or more wild yaks. As part of the same composition, three carnivores (tigers or wolves) chase the remainder of eight or nine wild yaks (several of them are are not visible in this image). This scene seems to convey that humans (or possibly mythic anthropomorphs) hunt wild yaks in the same manner as do carnivores. Perhaps this composition chronicles the hunting prototype. Tibetan literature holds that the origin story or mythic precedent (smrang) for the performance of rituals and other sacred duties was a cornerstone of early religion. Hence, there may possibly be some correspondence here between the written and artistic bodies of evidence. Just below the front legs of the horse the round head of a large anthropomorph is visible (middle of image).

Fig. 16. A fantastic bipedal figure with an elongated head, fingers spread widely and an ostensible male sexual organ (30 cm tall).

The strange appearance of this figure suggests that it had a special identity or function. One may speculate as they will, seeing a deity, shaman, epic personality, or something else in it. This isolated composition is situated below the line of walkers in Fig. 15.

Fig. 17. At the top of the panel above the petroglyphs illustrated in Fig. 15, a figure with a beak-like nose leads a horse (anthropomorph 25 cm tall).

This figure carries a long object (spear or walking stick?) over the shoulder. It appears to sport pointed headgear; hats of this shape were worn on the Changthang in premodern times as well. What might possibly be a sword or other implement protrudes from its waist. According to Sonam Wangdu (1994: 84), this is a male sex organ.

Fig. 18. Part of the line of 60 or so ‘backpackers’ on the east quarter of the main panel.

In the middle of the group a giant figure with walking stick has an animal-like head (33 cm tall). Only this figure’s head is above the ostensible trail used by the backpackers. The long object protruding in front of the legs is connected to an object that extends over the back. Thus it does not seem to be phallic in nature. Below this figure, a yak was carved. To the right of this yak and the giant is an elaborate ornithi-anthropomorphic figure (for a close-up view, see Fig. 21). Above the line of travelers, on the left, two yaks from the hunting scene in Fig. 15 can be seen. On the right, above the ‘trail’ several other figures form a shorter line of walkers.

Fig. 19. This part of the main panel is located to the east or right of that in Fig. 18.

The first figure in the line and those of the smaller upper line on the left side of the image are also visible in Fig. 18. Above these ambulatory figures two ‘men’ face off with rectangular shields and other objects in their hands (for more details, see Fig. 20). Above the fighters, a wild yak was carved (28 cm long). This animal appears to have been added later to the panel than other figures depicted in this image, because it was carved using a different technique and is somewhat less re-patinated. To the right of the duellers is another bird-like figure standing on its own. Further to the right, at the top of the panel, is an anthropomorph very similar in form to the one in Fig. 9 (23 cm tall). It carries a pike (?) and a round object (drum?) that appears to have streamers hanging from it. This figure also seems to have an animal head.

Fig. 20. A close-up of the two combatants or contestants in Fig. 19 (25 cm in length).

This scene portrays either a battle or martial contest in what could have been either a contemporaneous, historical, or mythic context. The two anthropomorphs (human as opposed to divine figures?) wear conical hats or helmets. According to Bon literature, ancient Tibetans had a variety of steel helmets (see the book Zhang Zhung, pp. 240, 241). The engraved helmets appear to have plumes or some other type of finial (called tru (’phru), this was considered the most vital portion of the helmet in Tibetan literature, the receptacle of the martial spirits). Each figure stands with legs spaced apart for stability, and they are shown moving towards one other ready to strike. The two ‘men’ grasp large rectangular shields; the one on the left is horizontally divided into four sections, the other in six sections. By depicting differently decorated shields, the carver stressed distinctions between the two combatants. These variations may possibly depict different standards or regimental / clan colors. In the rock art of Upper Tibet, shields are almost always quadrate in form, while in later times round shields made of wicker were used in western Tibet. The bodies of the two figures are also ornamented differently, and they seem to wield different style weapons in their hands. The weapon in the hand of the figure on the right resembles a dagger, but this is not a complementary fighting accoutrement to a shield. The weapon of the other figure could possibly be a lasso. Having a sword or some such smaller sharp-edged weapon with a banner attached is not practicable for fighting.

Fig. 21. The bird-like figure also seen in Fig. 18 (36 cm tall).

Above the triangular head of this figure lines radiate upwards, which may simulate feathers and horns (horned crowns were an important ritual and royal symbol in Upper Tibet, according to Bon literature). Streamers seem to extend out from the sides of the head. In historic times, spirit-mediums and bards in Upper Tibet had streamers on their headdresses. An X marks the round upper body of the figure. Perhaps this is a breastplate, as used by later spirit-mediums (some of these copper alloy ‘mirrors’ are pre-Buddhist in origin). On the right side of the figure, there is a round object, which probably represents a drum. The lower body seems to be clad in a long skirt of bird feathers. While many figures engaged in more mundane activities at Thakhampa Ri have conventionally formed human bodies, those such as this one have extravagant forms more congruent with sacred, heroic, or other privileged activities. This elaborately attired figure appears to be depicted in a ritual or mythic attitude consonant with that of a priest, medium, or deity.

Fig. 22. An analogous anthropomorph with an intricate rayed or feather headdress.

Sonam Wangdu (1994: 92) also provides a close-up photograph of this composition taken in more diffuse light. What appear to be ears and some facial features are recognizable. There are no implements visible in the outstretched forked hands of the figure. Its skirt is feathered or otherwise fringed.

Like Fig. 21 (also Figs. 23–30 and 32), Fig. 22 represents an exceptional human or supernatural being. I am most inclined to perceive these as priests or spirit-mediums attached to the band of individuals who created the rock art of Thakhampa Ri. I might further speculate that they are shown engaged in ritual activities seen as beneficial to the community and cosmos. Each of these ‘shamanic’ figures are portrayed with different attributes and appearances; this is perhaps to delineate sacral figures belonging to different clans or lineages. Bon literature tells us that each major clan had its own zoomorphic totem in ancient times. Avian features are still recognizable in the horned eagle eyes painted on the headdresses of Upper Tibetan spirit-mediums and in the plume of lammergeyer feathers they wear.

In the study of north Inner Asia rock art, unusual anthropomorphic figures are often compared or equated with shamanic activities of recent times. However, one must always bear in mind that such interpretations remain largely unverifiable. In the Tibetan context, we have the added benefit of many written accounts purporting to describe the priests and ritual activities of the distant past. These began to be compiled circa the 8th century CE. Nevertheless, as already noted, correspondences between the written and rock art records are best made in a generalized fashion.

Fig. 23. A bevy of extraordinary figures of the kind we have been examining.

These eight figures are 10 cm to 19 cm in height. They are located on the eastern quarter of the main panel of Thakhampa Ri. Each is presented below in more detail. The upper row of figures appears to have been made by one individual. Each of them stand, apparently playing a drum, which is consonant with a ceremonial or ritual scene. The lower figures are of the same type but may have been carved by others. The upper row of figures are barely discernible in Sonam Wangdu’s book (1994: 86).

Fig. 24. Figure on the left side of the upper row. This figure appears to bang a drum with flattened sides and a cruciform design. It has a spiked head, triangular upper torso and legs bared below the knee. Its head seems to be studded with seven feathers.

Fig. 25. The second figure (left to right) in the upper row. This specimen has a very similar type of headdress to the one in Fig. 24. However, its torso is diamond-shaped. The drum is divided into quarters. This depiction clearly gives the sense that the figure is beating a drum with its right hand. Behind the legs a tail-like object or article of clothing is shown.

Fig. 26. The third figure in the upper row. It is also attired in a garment that reveals much of the legs, and is depicted in the same attitude of beating a drum. However, its headdress has many fine points (feathers?). There is a tail-like extension behind the legs (slightly cut in the image).

Fig. 27. The fourth figure in the upper row. This specimen seems to sport horns resembling those of a blue sheep or some other ungulate. Its face is animal-like as well. Perhaps it is portrayed wearing a ritual mask. A drum seems to be tucked under the left arm. The torso has a lanceolate form. Its costume is with long bird-like fringes and the legs are bare below the knees.

Fig. 28. The figure on the right side of the upper row. Its head is bird- or deer-like. What appears to be a drum is just recognizable to the right of the spatulate torso. The skirt tails and bare legs of this specimen recall those in Fig. 27.

Fig. 29. A pair of figures in the lower row. They hold drums and have other characteristics already examined. The drum of the figure on the left is divided into a number of sections. These two figures appear to be performing together.

Fig. 30. The other figure in the lower row. Its style of headdress, triangular head, drum, fringe, and bare legs are already familiar to us. It body has an almost hourglass form.

Fig. 31. Two anthropomorphs just above the upper row of extraordinary figures presented above (each around 15 cm in height).

The different modes of carving suggests that these two figures were produced by different persons. The figure on the left appears to have a gaping mouth. The figure on the right seems to carry something on its back and has that same linear extension near waist level as do other compositions at Thakhampa Ri.

Fig. 32. Another extraordinary anthropomorph situated to the right of Figs. 23–30 (18 cm in height). It has a forked headdress, hourglass-shaped torso, and partially bared legs. It may also be shown with a drum in its left hand, but the carving is ambiguous.

Fig. 33. Two anthropomorphs confronting each other with bows and arrows (45 cm in length).

By pointing arrows at each other, this composition seems to depict mortal combat. These figures may have bird-like, or other kinds of, zoomorphic heads. Perhaps this is combat of a ritualized or mythic nature, but we have no way of really knowing. Each fighter is armed with a recurve bow, a powerful variant of this common weapon. The figure on the left carries something on its back and seems to be horned, while the one on the right has a tall headdress. Below them another anthropomorph appears to be looking on. It also has a head or mask that seems zoomorphic in nature.

This concludes our examination of the main panel at Thakhampa Ri. I hope you have enjoyed it. As we shall see next month, this site boasts more diversity in its art, chronicling other aspects of life in ancient Upper Tibet.

Next Month: More spectacular rock art from other panels of Thakhampa Ri!