January 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Flight of the Khyung wishes you a soaringly Happy New Year! This month’s newsletter presents the final in a series of articles on Spiti, a region on the margin of the Tibetan plateau in northwestern India. Since May of last year there have been eleven different articles on Spiti in Flight of the Khyung. Taken together, these constitute a book-length project. I trust they will prove a useful resource in the study of ancient Spiti.

Thanks to the generous support of the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) I was able to write up and present my findings on Spiti in these newsletters. I am also most grateful to Joseph Optiker (Switzerland) for funding the 2015 Spiti Antiquities Expedition.

This Flight of the Khyung sheds light on the ancient burial grounds of Spiti. Sadly, there is very little left to illuminate. In the last few years the tombs of Spiti have been thoroughly plundered, destroying scientific evidence like a house burnt down to the ground. In conflict zones of the world the degradation of archaeological resources is ignited by deadly forces. In Spiti, a land of peace and tranquility, there are no such extenuating factors. The eradication of its archaeological wealth is all down to greed and ignorance.

The state of archaeology in Spiti today can be compared to viewing the world through a keyhole. A little can be gleaned here, something made out over there, but these are mere drops in a veritable ocean. Study under these conditions is often referred to as ‘salvage archaeology’, but in the abysmal case of Spiti it is better described as blindman’s bluff archaeology!

This newsletter is very much enhanced by the inclusion of articles by James Wainwright and Neil Howard, experts in their respective fields of study. The contributions made by Wainwright and Howard (both from the UK) pertaining to ancient mortuary traditions complement my own study.

On another note, my new article available online reviews the origins and development of ancient civilization in Upper Tibet. The abstract and promotional materials are freely available on the Popular Archaeology website, but the article itself is behind a pay-wall. However, for just $9 per year, a subscriber has access to dozens of articles and many other features, including cutting-edge research in archaeology. Please see:

“On the Roof of the World: Discovering the Forgotten Civilization of Zhang Zhung”, in Popular Archaeology, December 2015. For freely available materials:

http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/winter-2015-2016/article/on-the-roof-of-the-world-discovering-the-forgotten-civilization-of-zhang-zhung

http://popular-archaeology.com/issue/fall-2015/article/revering-ancient-gods-on-the-roof-of-the-world

The Ancient Burial Sites of Spiti: The indigenous socioeconomic and cultural order and trans-regional communications in the era before the spread of Buddhism

Introduction to the ancient burial monuments of Spiti

Before writing this article I pondered over how much should be revealed about the ancient burial sites of Spiti, concerned that disclosure might lead to more looting and destruction. Upon further reflection, I decided to divulge all what I know. Let me share with you my thinking on this matter.

Both the inadvertent opening of tombs in Spiti and their ransacking depend on a veil of ignorance. So long as government authorities and academic institutions do not know or care about the problem, these illegal activities will continue to occur. My intention in writing this article is to shine light on the deeds of those involved in plundering and destroying the burial sites of Spiti. By furnishing explicit information about ancient cemeteries I hope to encourage the Indian government and academia to take resolute action. They have been dragging their feet for years in this regard. In any case, ignorance can no longer be a pretext for disregarding the critically endangered cultural heritage of Spiti.

Unfortunately, no archaeological survey of the mortuary sites of Spiti has been undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). In fact, the pre-Buddhist heritage of all Tibetan plateau regions in India has been poorly studied by the ASI. There are some positive signs emerging though: in 2015, ASI personnel briefly visited several archaeological sites in Spiti and preparations for the first excavations and conservation of rock art are now in the planning stage.

The involvement of the ASI in Spiti is a welcome development, but it is not sufficient to stem the loss of the ancient cultural wealth of this vulnerable region. Concerted action is needed on the part of government officials, in particular from the two senior-most officers based in Spiti, the ADC (Additional Deputy Commissioner) and SMD (Sub-Divisional Magistrate), who must take it upon themselves to educate locals about the value and vulnerability of ancient burial sites. If necessary, law enforcement agencies may be called upon to act. It is also essential that Buddhist lamas and other highly respected members of the community educate themselves about their ancient cultural legacy and the threats facing it and provide proper guidance to the people.

Practically speaking, any further construction projects in the proximity of villages in Spiti should only be undertaken with expert oversight to prevent more tombs from being inadvertently or purposely destroyed. A procedure could be developed whereby cultural permits become mandatory for all forms of construction in Spiti. Concerned authorities working in collaboration with the ASI and State Museum of Himachal Pradesh, etc. could sanction the issuance of construction permits after proposed building projects have been assessed for their archaeological impact and any needed conservation measures instituted.

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of mortuary sites for understanding the past. Unlike remains left on the surface, which are often scoured clean by people and the elements over the centuries, monuments concealed underground can act as a time capsule, locking away physical evidence of the distant past. Moreover, organic remains (corpses, wood, textiles, cordage, vegetable matter, etc.) obtained in tombs can be dated scientifically (using radiometry and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, etc.), anchoring burials firmly in time, the foundation of modern archaeological inquiry. Even ceramics deposited in graves are often datable by the thermoluminescence technique (measuring discontinuities in the conduction of ionizing radiation in crystalline materials exposed to high temperatures). In contrast, the scientific dating of rock art is still not reliable or cost effective.

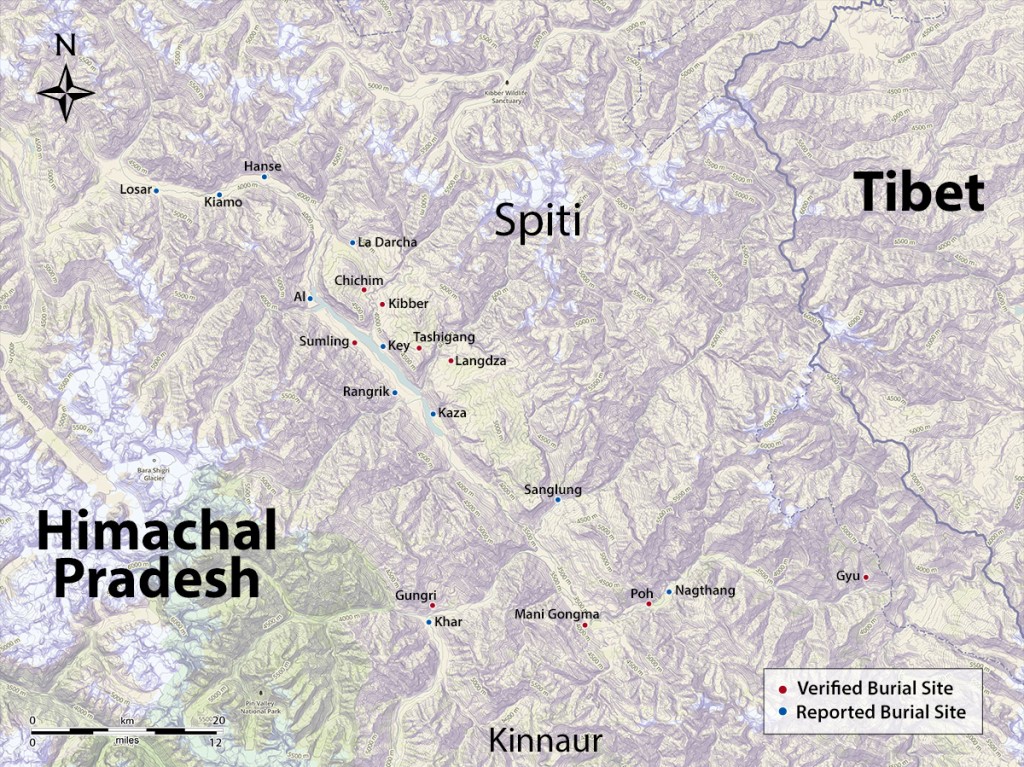

A group of concerned local citizens and friends who call themselves the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society (SRAHS) have documented the physical remains of cemeteries in a number of villages in Spiti. They have also received reports of burial grounds in other villages but these have not yet been verified. The SRAHS has agreed to disseminate this newsletter to concerned government officials, Buddhist clerics and other luminaries in Spiti and New Delhi.* May it serve as a clarion call to action!

I heartily thank members of the SRAHS for their support and cooperation. Not only did they facilitate my research and exploration in Spiti, they freely shared their own findings with me. Without their active assistance, the writing of this month’s newsletter would not have been possible.

Over the last three years, the SRAHS has compiled a list of around fifty tombs, points for further inquiry and action. The number of tombs registered by the SRAHS, however, is likely to be just a small fraction of the actual number that has been sacked in recent years. Perpetrators do not often trumpet their nefarious activities.

The plundering of ancient graves in Spiti has reached epidemic proportions in the last five years, leading to the loss of a huge amount of cultural artifacts and scientific knowledge. Many tombs have been wiped out by the construction of houses and buildings or by land-clearing heavy machinery.

Since the 1980s and particularly in the last few years, dozens of tombs have been discovered in and near the villages of Spiti. However, not one of these tombs has been properly studied or preserved. Often when local people encounter tombs they are emptied of valuable artifacts, all other objects and human remains being discarded. Both laypeople and monks and nuns are responsible for this plunder.

It is especially regretful that those in the religious orders in Spiti are directly and indirectly involved in the looting of tombs. Buddhism is based on an ethic of doing no harm but that does not seem to extend to the region’s pre-Buddhist heritage. A millennium of the Spitian population dismantling its ancient cultural legacy has expurgated most of the early historical record. However, the active elimination of ancient customs and traditions has very much intensified in the last twenty or thirty years.

The problem of looting is exacerbated by the proximity of ancient cemeteries to the villages of Spiti, making despoilment a relatively easy task. Opened tombs are occasionally covered back up again (usually after being emptied), but this is an exception because the sites are usually given over to redevelopment.*

The pilfering of ancient tombs in the Tibetan world however is nothing new. The first recorded example concerns the looting of the royal tombs at Chonggye (’Phyong-rgyas) in southern Tibet more than a thousand years ago. Upper Tibetans aver that zi stones and golden articles were recovered in olden times from the graves of wealthy Mon, an ancient tribe thought to have once inhabited the region. These precious items became the property of those who found them, and in some cases, they were passed down for many generations.

How can this colossal disrespect of the past be explained? Traditionally, Spitians and other Tibetan peoples kept excavation to a minimum, not wanting to hurt small creatures living in the soil and fearful of angering subterranean spirits like the sabdak (sa-bdag) and lü (klu). However, these age-old sensibilities and prohibitions have broken down with the advent of acculturation, modernization and the market economy. As we saw in earlier newsletters in this series, the blithe disregard Spitians have for their pre-Buddhist heritage also blights rock art, around half of which has been lost in the last decade alone.

A general description of the ancient burials of Spiti

My preliminary assessment of major tomb types from in Spiti is based on an examination of surface remains at just a few sites and photographs furnished by the SRAHS. Most tombs disturbed in Spiti have few defining features left either on the surface or below it.

Generally speaking, the ancient tombs of Spiti appear to be of two main types: cist graves and shaft graves possibly with wooden substructures.* Cist tombs consist of stone slabs or smaller rocks making up the four walls, the roof and sometimes the floor of a burial chamber. Cist tombs are usually quadrate but variations in form have been documented. Cist burials are common in Tibet and many regions of north Inner Asia and further afield. They are also observed in Kinnaur and Lahul, regions adjoining Spiti. Some cist tombs have rings or squares of stone or small mounds on the surface, forming the superstructure of the burial.

The ancient custom of interment in carefully prepared tombs contrasts with methods of corpse disposal in contemporary Spiti, which have prevailed over the last thousand years of the Buddhist era. These methods are comparable with other regions of cultural Tibet, foremost among them being the so-called ‘sky burial’ or dispersion by birds (bya-gtor). For an account of sky burial in Spiti, see Singh, Bhagwan. 1933: “Disposal of the Dead by Mutilation in Spiti (W. Tibet)”, in Man, vol. 33 (Sep., 1933), pp. 141–143. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

Shaft tombs are underground chambers with a passageway or shaft leading up to the surface, which was sealed after interment. The burial chambers in shaft tombs are usual round, ovoid or oblong. Shaft tombs may be multi-chambered or have a chamber subdivided vertically in two or more levels. Shaft tombs seldom have superstructures with stone elements. In Guge (western Tibet) and Mustang (Nepal) wooden coffins and other grave furniture are sometimes installed in shaft tombs.*

For a comparative study of tombs in western Tibet, Kinnaur and Mustang, see Aldenderfer, Mark, 2013: “Variation in mortuary practice on the early Tibetan plateau and the high Himalayas”, in The Journal of the International Association for Bon Research, vol. 1, pp. 293–318. New Horizons in Bon Studies 3. The International Association for Bon Research.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/jiabr/pdf/JIABR_01_14.pdf

Internment with grave goods represents an archaic cultural tradition discontinued in western Tibet in the 10th century CE with the spread of Buddhism, as indicated in a number of Tibetan historical and ritual texts.* As none of the tombs in Spiti have been scientifically dated, a broad range of periods must be considered. Data from burials in adjoining regions indicates that cist and shaft tombs in Spiti were constructed in the Iron Age (600–100 BCE), Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE) and Early Historic period (600–1000 CE).† The evidence presented below, however, suggests that most artifacts and human remains uncovered in Spiti to date are probably attributable to the Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

See “The decree of Lha Lama Yesheö”, “A Review of the Early Cultural History of Spiti – Part One”, May 2015 Flight of the Khyung. Also see my 2013: Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet: Archaic Concepts and Practices in a Thousand-Year-Old Illuminated Funerary Manuscript and Old Tibetan Funerary Documents of Gathang Bumpa and Dunhuang, pp. 119, 142, 156. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

On chronological nomenclature employed for Spiti, see July 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

Standing stones, large burial tumuli, stone enclosures, mausolea, funerary temples or other salient signs of mortuary sites have not been discovered in Spiti. The conspicuous burial grounds and necropolises with these features that characterize many burial sites in Upper Tibet are absent in Spiti. As with a lack of large residential monuments, this evidence strongly suggests that Spiti lagged behind its big neighbor in terms of socioeconomic and technological development. Also, the absence of complex mortuary features on the surface may be indicative of an alternative funerary ritual regimen. One might argue that the more elementary burials of Spiti allude to ritual procedures and objects that were not as elaborate as those in Upper Tibet. Nevertheless, the degree of monumental complexity observed in Upper Tibet and Spiti could also be attributable to social tastes or cultural vernacularism. Social and cultural variability in Spiti and Upper Tibet is discernable in the rock art record.

A landscape devoid of prominent mortuary markers can also be accounted for by environmental factors (lack of large stones of suitable strength, paucity of high open areas away from settlements, etc.), which dissuaded the inhabitants of Spiti from erecting necropolises and other monumental burial structures. Indeed, structural variations in funerary sites in the badlands of Guge appear to be environment driven, a region that otherwise was closely allied culturally with the rest of Upper Tibet in antiquity. Guge, like adjacent Spiti, does not have large necropolises.

If and when controlled archaeological excavations are made in Spiti, as opposed to the free-for-all looting of the present time, the chronology and character of its mortuary tradition will emerge more clearly. This will facilitate an assessment of the paleocultural status of Spiti and its links with neighboring territories.

A preliminary survey of the ancient burials of Spiti

Although this is just a preliminary survey of Spiti’s pre-Buddhist burial sites, I hope it will stimulate interest in archaeological exploration and conservation in the region. Policy makers in India and the academic community, please take note.

This survey may disappoint some readers for its cursory treatment of the subject. I, too, am disappointed by the lack of data on ancient burial practices in Spiti. Although many tombs have been unearthed, almost all have been wrecked, effacing evidence that otherwise could have been used by archaeologists to reconstruct the ancient cultural and environmental history of the region.

Less than half of the tombs listed by the SRAHS have been verified through visual inspection by members of that organization. Their count is based on information from local sources as and when it becomes available, not on the systematic collection of standardized forms of data. Although theirs is not a scientific survey per se, we must be grateful to the SRAHS for their efforts and for alerting concerned officials and academics to the existence of the tombs, many of which would have been lost forever without their intervention.

The SRAHS tally of tombs up to May 30, 2015 is as follows:

| Village Name | Number of Tombs Reported |

| Gyu (rGyu) | 4–5 |

| Nakthang (Nags-thang) | 1 or more |

| Poh (sPo) | Around 10 |

| Mani Gongma (Ma-ṇi gong-ma) | 2 |

| Khar (mKhar) | 1 |

| Gungri (dGung-ri) | 4 |

| Sanglung (gSang-lung) | 2 |

| Tashigang (bKra-shis-sgang) | 1 |

| Langza (Lang-rdza) | 4–7 |

| Rangrik (Rang-rigs) | 1 or more |

| Sumling (gSum-gling) | 2 |

| Al (’Al) | 1 |

| Key (dKyil) | 1 |

| Kibbar (dKyil-bar) | 3 |

| Chicham (dKyil-khyim) | 9 |

| La Darcha (?) | 1 |

| Hanse (Han-se) | 1 |

| Kyomo (sKyid-mo) | 2 |

| Losar (Lo-sar) | 1 |

Since the compilation of this list, it has come to my attention that tombs have been discovered in the village of Lari (La-ri) during the expansion of apple orchards.

The tally of ancient burial sites in Spiti is remarkable for its uniform spatial organization. Most tombs have been come across in and around the contemporary villages. The location of most tombs at what was the traditional periphery of villages strongly suggests that these settlements were contemporaneous with the mortuary sites. It seems likely that the burials were originally placed some distance from residential structures and agricultural fields. With the recent expansion of village habitations and fields in Spiti, ancient cemeteries are increasingly being encroached upon.

Fig. 1. The concrete hulk of a new Buddhist temple being constructed on the site of an ancient cemetery, Gyu.

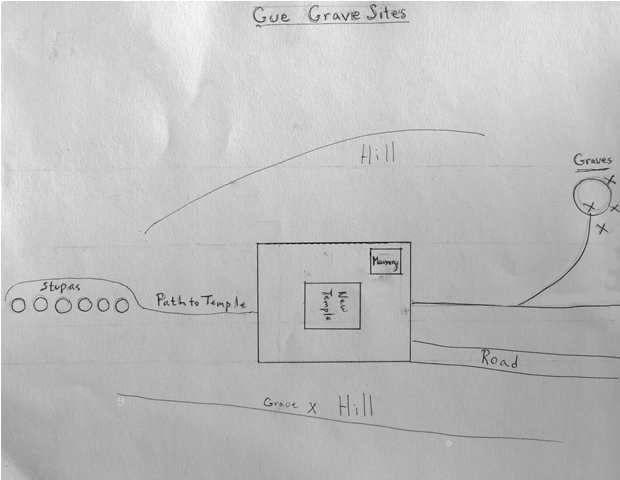

Fig. 2. Sketch map of Gyu mortuary sites drawn by the SRAHS. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

This new Buddhist facility sits on a rocky spur just above the modern village of Gyu. It is reported that during the leveling of the site for the construction of a temple, parking lot and link road a number of tombs were uncovered. Undeterred by this discovery, construction workers were advised to throw the human bones and ceramics down the slopes which they did. Many artifacts were discovered when the tombs were opened. Except for a few stones strewn about nothing remains of the cemetery. When I asked Jigme Tenzin Dorje Rinpoche (’Jigs-med bstan-’dzin rdo-rje), the builder of the new temple, about this state of affairs, he replied that he was not informed about the discovery of tombs at the site.

Fig. 3. Ceramics, shell objects and musk teeth from tombs at Gyu, Spiti. These objects were donated to the State Museum, Shimla. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 4. Other side of ceramics, shell objects and musk teeth found in Gyu. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Thanks to the good offices of the SRAHS, a number of artifacts from the tombs of Gyu were documented and guidance given on how they should be conserved. Objects collected from two tombs by a local man named Nyima Namgyal were donated to the Himachal State Museum in Shimla on October 11, 2014. The objects this individual donated and their positions in the above photographs are as follows:

- Two pieces of combed or impressed greyware belonging to globular jars from different tombs (left and right sides of upper row)

- Cylindrical shell bead (right side of middle row)

- One star-shaped shell object (right side of lower row)

- Four perforated cowry shells (right portion of middle row)

- Two larger perforated shells with engraved parallel lines along the edge (middle of upper row)

- Disc with two central perforations (center of middle row)

- Hemispherical grey shell with off-centered keyhole near the apex (extreme left of lower row)

- Disc with three perforations and engraved parallel lines along the edge (second from left in lower row)*

- Four musk deer tusks (left half of middle row)

This shell has been identified as Turbinella pyrum, a species native to intertidal coral reefs on the east coast of India. See p. 13 of Mukherjee, Arati Deshpande / Bhatt, R. C. / Saklani, P. M. / Nautiyal, Vinod / Chauhan, Hari / Bist, Kavita / Panwar, B. S. / Choudhary, Satish. 2015. “A Note on the Marine Shell Objects from the Burial Sites of Malari, Lippa and Ropa in the Trans-Himalayan Region of India”, in Archaeo + Malacology Newsletter (ed. A. C. Christie), no. 25, pp. 9–15.

https://archive.org/details/AMWGNewsletter25

A star-shaped button from a grave at Gyu was also donated to the Himachal State Museum by a local person named Bhutit. The donation of artifacts uncovered in tombs in Gyu by two individuals is a praiseworthy act (note however that nothing of significant market value was handed over). These finds are but a small part of what was recovered from tombs plundered in Gyu by local persons.

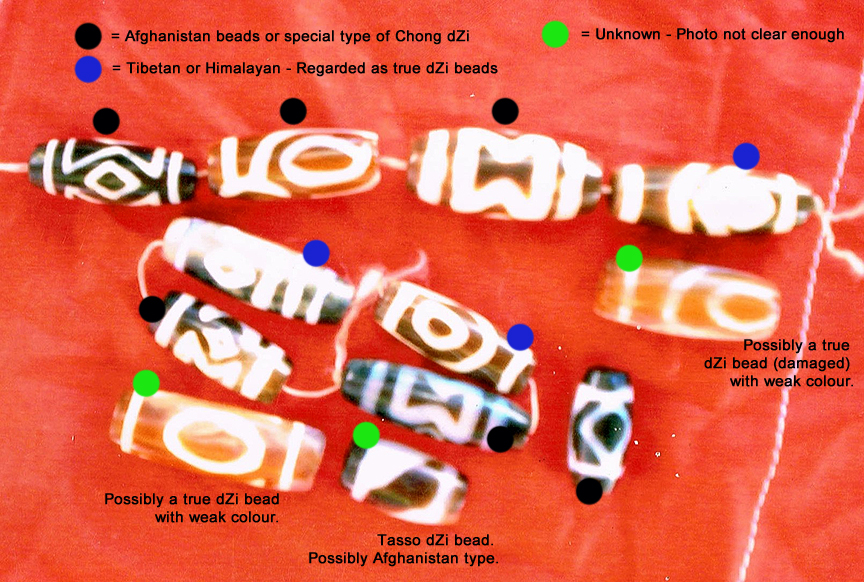

Fig. 5. Ancient patterned chalcedony (agate, onyx, etc.) and possibly carnelian beads recovered from tombs at Gyu. The white line or lines circumscribing the ends of most of the beads are known as ‘mouth design’ (kha-ris). The oval and diamond patterns are called ‘water eye’ (chu-mig, a name for springs in Tibetan, which according to Tibetan folklore, are from where many zi originate). The design consisting of an hourglass pattern opposite an eye is called ‘sky portal, earth portal’ (sa-sgo gnam-sgo). Photo courtesy of SRAHS (unfortunately, the photos made available are somewhat out of focus).

The discovery of high quality patterned chalcedony beads in excellent condition in the tombs of Gyu is very noteworthy.* These beads are known as zi (gzi) and chong (mchong) in Tibetan.† It is reported that the beads shown above were procured by a well-known antiquities dealer based in the district capital of Kinnaur. It is claimed that this dealer sold at least some of his acquisitions to Chinese buyers in Singapore and China. In 2014, he is also supposed to have obtained three zi beads with eyes unearthed from the Kinnauri village of Ropa in 2014. These highly valuable beads are said to have been hidden in a ceramic pot.

The arid and frigid climate, intense ultraviolet radiation at high altitude and sheltered placement underground are ideal conditions for the preservation of material remains.

For studies of zi stones, see:

1) Lin, Tung-Kuang. 2001: The Gzi Beads of Tibet. Taiwan: Liao, Yue-Tao.

2) Ebbinghouse, D. and Winsten, M. 1988: “Tibetan gzi (gZi) Beads”, in The Tibet Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 38–57. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

3) Norbu, Namkhai. 2009: The Light of Kailash: A History of Zhang Zhung and Tibet, vol. 1 (trans. D. Rossi). Merigar: Shang Shung Publications. See pp. 167–171.

4) Allen, J. D. 2002. “Tibetan Zi Beads: The Current Fascination with their Nature and History” in Arts of Asia, vol. 32 (no. 4), July/August, pp. 72–91. Hong Kong.

5) Chayet, A. 1994. Art et Archéologie du Tibet. Paris: Picard. See p. 60.

6) Tucci, G. 1973. Transhimalaya (trans. J. Hogarth). Reprint. Dehli: Vikas Edition. See p. 40.

At current market prices, the zi found in Gyu are worth thousands of dollars. The discovery of zi beads in Gyu and other places in Spiti in the last few years has opened up a veritable Pandora’s Box. The desire to find valuable artifacts concealed in Spitian tombs consumes a small but dedicated bunch of treasure seekers, while other less obsessed locals hope that they may simply stumble upon a bonanza.

The zi from Gyu pictured above are a surprisingly diverse group of beads, representing different types of chalcedony and perhaps carnelian (hard to tell from the photos). The ground of the beads comes in a variety of colors, ranging from light amber and tan to reddish, brown and black. These stones exhibit varying degrees of translucence and are exceptional for their form and sophistication. The designs on these beads were produced through an elaborate process of etching, application of mineral pastes and annealing, an example of ancient lapidary technology of considerable refinement.

Fig. 7. Two pottery sherds collected in Gyu by members of the SRAHS. The sherd on the right is from a smooth-walled greyware vessel. The sherd on the right is a fabric- or basket-marked thin-walled piece of redware. Such types of ceramics are likely to have come from local tombs.

Over the last few years, members of the SRAHS have been collecting ceramic fragments in various villages of Spiti. Most of these sherds are from unglazed hand-built vessels. Further research will be needed to pinpoint the techniques of fabrication (e.g., coil, paddle, molding, etc.). The collected fragments contribute to the establishment of a typology of ceramics in Spiti, useful in arranging vessels in chronological order (based on seriation methodology). However, to accurately sequence ceramics, having examples from secure stratigraphic contexts is essential. And this will only be possible if tombs undisturbed by modern human activity can be properly studied by archaeologists.

Fig. 8. Smooth-walled and cord-marked redware from the village of Lari. Note what appears to be part of a handle marked “Lari”. Some of these ceramics may have been deposited in tombs.

Fig. 9. Pottery sherds exhibiting different methods of fabrication recovered in Tabo. Many of these ceramics appear to belong to the Buddhist era (post-1000 CE).

Fig. 10. A variety of sherds from Poh. A funerary function for some of these ceramics may be indicated.

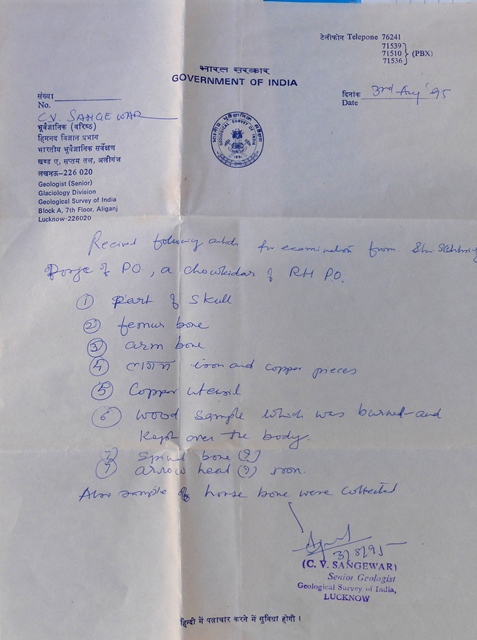

Fig. 11. A memo from the Geological Survey of India dated August 3, 1995, acknowledging the receipt of human bones and other objects discovered in a grave accidentally opened in the village of Poh. What has become of these human remains and artifacts is unclear. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Unfortunately, the tomb discovered in 1995 from which the objects pictured above came is the not the only one to have been violated in Poh. In the last two or three years, other tombs were unearthed during the construction of a government facility outside the village. Human bones and artifacts were reportedly dug up at this site.

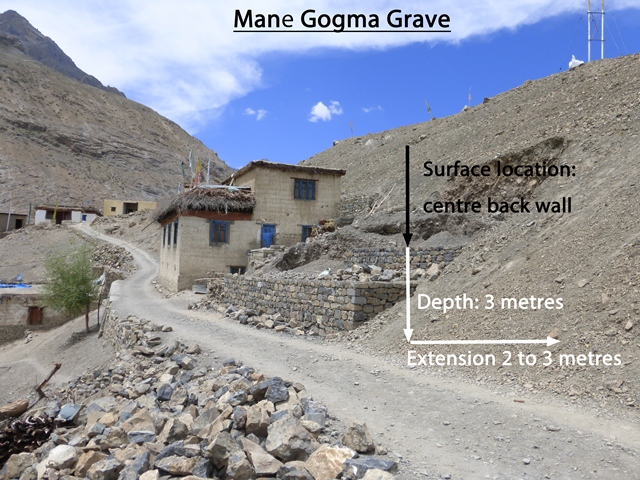

Fig. 12. Location of two tombs in the village of Mani Gongma. They are situated on a ridge in or near the old village of Mani Gongma, raising questions as to the placement of burials in relation to ancient habitations. In recent years the village has spread downward to impinge upon agricultural fields. Photo and its notation courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 13. Close-up of burial site on left side of fig. 12. This shaft tomb was destroyed when a retaining wall was built along an access road. The burial chamber measured approximately 2 m x 3 m. It is clear from mortuary sites in Gyu and Mani Gongma that steep slopes were sometimes chosen for the placement of tombs. Locating burial grounds in this way conserved arable land. Photo and its notation courtesy of SRAHS.

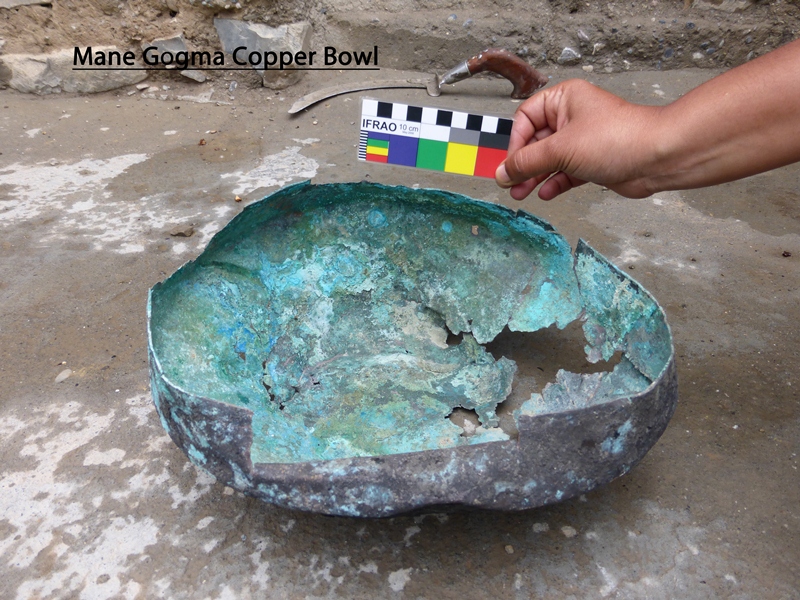

The first known documentation of tombs in the village of Mani Gongma occurred on August 7, 2014, when a Ms. Rajini Murali was interviewing villagers for the Nature Wildlife Foundation. In one of her interviews, Rajini was told that several tombs had been discovered in the village. She was subsequently introduced to the people who had rooted up the burials. She was permitted to take photos of objects and human remains lifted from the graves. On August 14, 2014, members of the SRAHS accompanied Rajni to Mani Gongma in order to verify the report, conduct interviews and take more photographs. The SRAHS was able to collect ceramic vessels from a burial site that was soon to be built on, sparing them from destruction.

I quote the report submitted to the SRAHS by Rajini Murali in full:

I was staying in the Nomo’s [senior female figure of ruling family] house in Mani on the 7th of August 2014 as I was interviewing people for my work. In the evening while I was talking to Nomo and her neighbor Sonam, I mentioned to them that I had come to Poh to look at the rock art. I also mentioned graves and pots that were found in the graves. They then said that they had found graves in Mani as well. They said they had found pots in these graves. I asked them if anyone in the village had kept the pots and they said that there was one in this house. I asked him to show me the pot and he went into the puja room and brought back the pot. It was a small black pot about ten to fifteen cm [in height] with two lines engraved on the neck of the pot. They were using it in the puja room to burn juniper which is used as incense. I asked them if there were anymore pots in the village and they said that many people had kept the pots. They then told me that some people had kept the femur bone from skeletons and were using it for their puja everyday. I asked if they could show me the bone and they said they would take me to the person’s house.

Early next morning we went to the person’s house that had kept the bone and asked him if he could show it to us. He showed us the femur. He had colored the head of the bone red and the rest of the bone was covered with copper wire [to create a rkang-gling horn]. He also mentioned that he had found a grave near his old house four years ago when he was building a new house. The grave, he said, was like a cave full of pots and he even found gold. He donated the gold to Dankhar monastery. He showed me two pots from the grave. One was a large earthen brown pot about 50 cm tall and it had handles, the other was a copper pot that looked like a round, wide basin about 30 cm wide and 15 cm tall. He said there were more pots in the grave which he had left as it was. He had put the mud back on the grave and left everything there. The grave is located right beside his house.

Fig. 14. Cord-marked bulbous jar of buffware picked up from Mani Gongma tomb mentioned above in Rajini Murali’s report. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 15. Copper basin found in same Mani Gongma tomb mentioned above in Rajini Murali’s report. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 16. Shaft tomb opened in Mani Gongma in fig. 13. Note the wooden plank, which was part of a coffin or some other mortuary structure. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 17. Member of SRAHS photographing interior of burial chamber in fig. 13. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 18. Ceramic vessels, sherd and what appear to be caprid bones recovered from tomb in fig. 13. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 19. Close-up of globular pot and wooden objects in fig. 17. The thin-walled globular jar with flared neck appears to have been fitted with two handles, one of which has broken off. Both pieces of wood have been worked. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 20. Animal bones (including bovid) and planks of wood recovered from tomb in fig. 13. The planks may have been used in the construction of a catafalque, coffin or burial vault. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Ceramics of coarse-textured redware and buffware with impressions made by marking with cords, fabrics or baskets appear to be the most common types of vessels used in mortuary sites in Spiti. It has been pointed out to me that the molding of most Spitian mortuary vessels was probably supported by a device of basketry or wood with a textile covering. These kinds of ceramics have been collected all over Spiti, helping to define the region culturally as well as technologically in antiquity. This coherence in the assemblage of ceramics is reflected in the rock art record as well, demarcating a cultural province allied with adjoining regions.

Fig. 21. Ceramic fragments from three different vessels collected near Gangchumik (sGang-chu mig) of the kind that may have been deposited in graves. All three sherds have impressed decorations created using various materials.

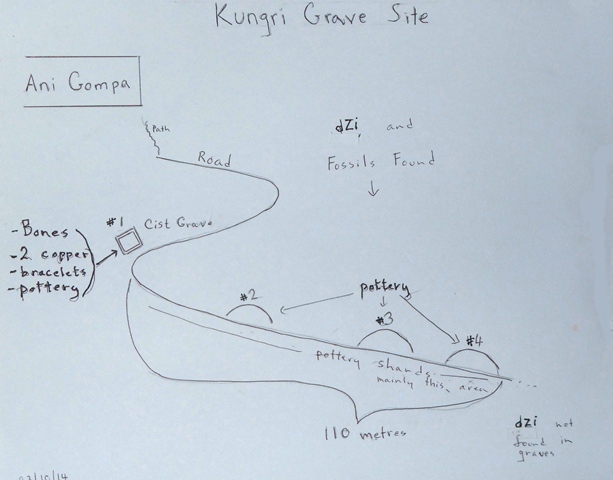

At least four tombs have been documented in the village of Gungri. Like other ancient mortuary sites in Spiti, these structures have been heavily disturbed by construction and grave robbers. Very little remains detectable on the surface, precluding a detailed assessment of the burial structures. Ceramic fragments and valuable zi stones were discovered at the Gungri burial site.

Fig. 22. Sketch map of grave sites and objects documented in Gungri, Pin valley. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 23. Site of partially excavated tomb, Gungri. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 24. Nun posing at site of partially excavated tomb, Gungri. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 25. Site of excavated tomb, Gungri. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 26. Ceramic sherds from smooth-walled vessels collected in Gungri, many of which presumably came from tombs.

Fig. 27. Banded agate retrieved by local woman from one of the tombs of Gungri. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

The striped design of this zi bead with a camber is the result of a sophisticated ancient fabrication process. Highly prized but quite common, striped zi of this type are now distributed throughout the Tibetan world and are widely traded. It is reported that many zi stones have been recently come upon in the tombs of Gungri.

Fig. 28. Ceramics collected from the village of Demul (rGyu-dngul) in the Lingti (Gling-ti) valley, Spiti.

The sherds pictured above represent an assortment of ceramic fabrics and vessels that appear to have been produced over a wide range of time. The buffware fragments (both lightly and deeply impressed) belong to ceramics types that may have been deposited in Spitian tombs. It has been pointed out to me that the two deeply furrowed sherds in fig. 28 appear to have been produced through scratching with a comb-like implement.

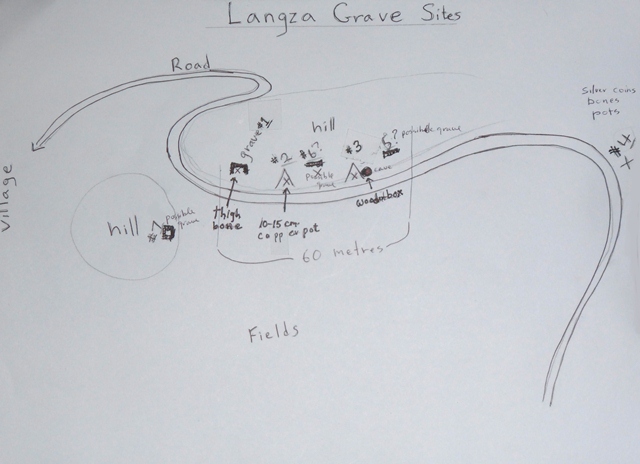

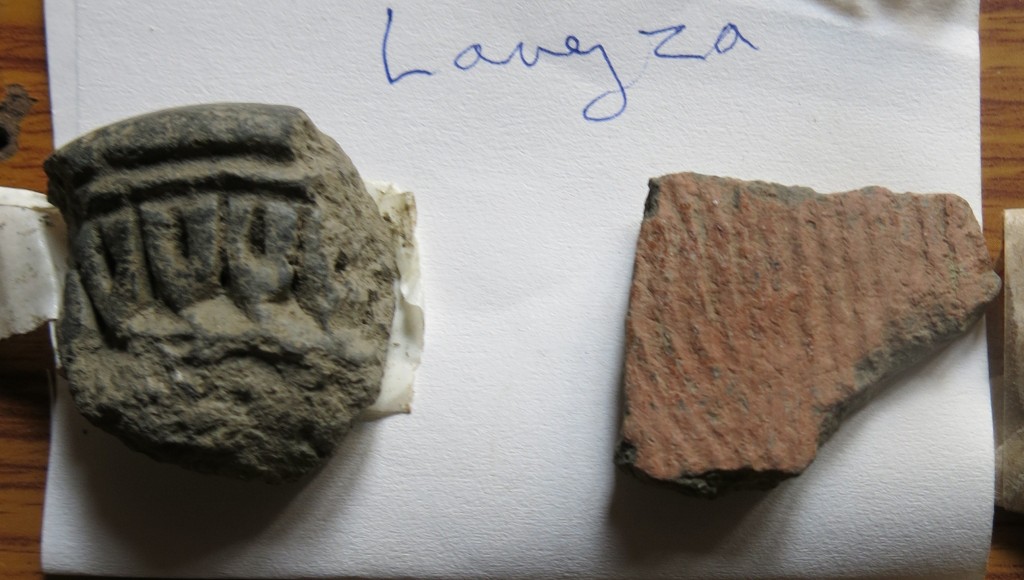

The existence of at least four tombs near the village of Langdza (Lang-rdza) has been documented by the SRAHS. These tombs were cut open during the construction of an access road to the village. In addition to human remains, wooden fragments were discovered in the tombs of Langdza.

Fig. 29. Location of some tombs near Langdza village. Photo and notation courtesy of the SRAHS.

Fig. 30. Sketch map of burial grounds in Langdza. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 31. Structural and human remains exposed during road construction, Langdza. This tomb appears to have had a stonewall chamber. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 32. Interior of tomb with wooden structural element, Langdza. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 33. Fragment of the stone substructure of a tomb largely obliterated during road construction. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 34. Wooden members protruding from an excavation at the Langdza burial grounds. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 35. Two sherds of pottery collected by the SRAHS in Langdza. The cord-marked buffware fragment on the right is of a type that was used in mortuary rites (non-funerary functions for these ceramics may also be indicated). The thick-walled greyware fragment on the left with its stamped or molded decorations is of a type that is probably of much more recent manufacture.

As in Langdza, at least one tomb was discovered outside the village of Tashigang during construction of a link road. Human bones and ceramics were collected from the burial.

Fig. 36. A tomb (rocky area in middle of photograph) at Tashigang sliced open by road construction. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 37. Human skull and other bones found inside tomb in fig. 36. Note the stacked stones behind the skull, which presumably formed part of the burial chamber. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 38. Three ceramic bowls from the tomb in fig. 36. The broken bowl with a wide pedestal and the lighter colored bowl it cradles are smooth walled. The conical bowl in the background is cord marked. The coarse texture of these kinds of funerary ceramics is clearly visible along the break in the footed bowl. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 39. Two other ceramic vessels retrieved from the tomb in fig. 36. The buffware jar in the foreground has a rounded bottom, squat, cord-marked body, a single loop handle, smooth-walled neck, very wide mouth and slightly turned out rim. The jar in the background exhibits the same fabric and surface treatment. This bulbous pot has a narrower neck terminating in a rim without any eversion. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 40. Cord-and fabric-marked fragments of redware and buffware collected from the disturbed tombs of Tashigang. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

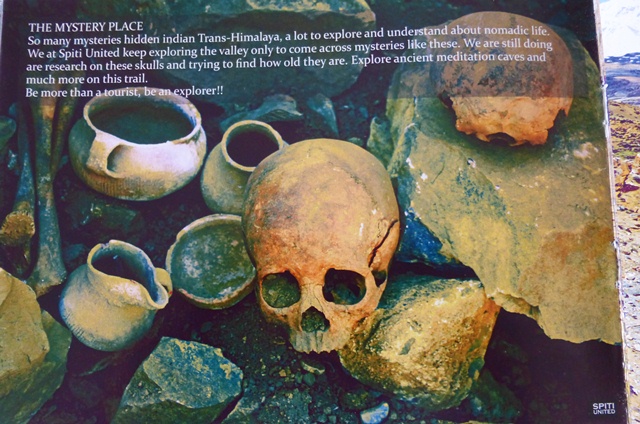

Fig. 41. Ceramic vessels and human skulls removed from the tomb at Tashigang and used as promotional materials for a tour company called Spiti United. Note the cord-marked vessel with spout and handle on the lower left side of the photograph.

It was reported that when members of the SRAHS approached the proprietor of Spiti United and asked about the status of the objects removed from the tomb at Tashigang, he became aggressive and threatening. Only the support of the civil administration, police, military and Buddhist religious establishment can counter those involved in the antiquities trade of Tibetan plateau regions in India.

At least three tombs have come to light in the environs of Kibbar village. It was reported to the SRAHS that a Kibbar villager named Palden Dhondrup (dPal-ldan don-grub) discovered a tomb while enlarging a field around 25 years ago. This man says that he saw a human skull and other human bones in the tomb, which were left undisturbed. A small ceramic bowl that had come to the surface was discarded. Members of the SRAHS observed the collapse of the ground surface at what might be the roof of a burial chamber at the grave site described by Mr. Palden Dhondrup. Bones and artifacts have been encountered in the vicinity.

Fig. 42. Site of tomb unearthed by Mr. Palden Dhondrup at Kibbar. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 43. In situ capstones of a gutted tomb, Kibbar. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 44. Cord-marked earthenware sherds detected near the Kibbar burial sites. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

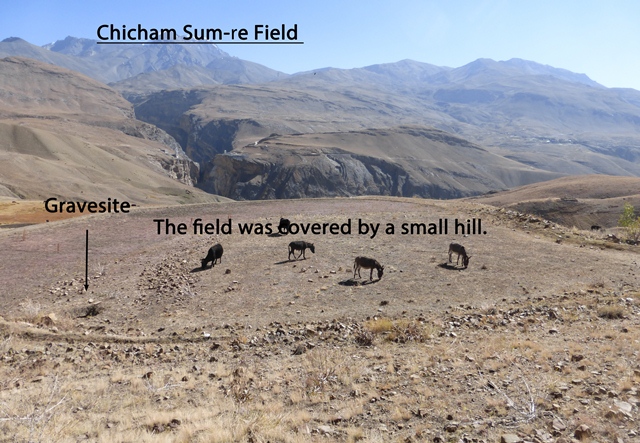

No less than nine tombs have been documented in the village of Chichim, most of which have been opened by local residents, revealing various ceramic vessels, stone beads and human bones. These tombs were opened during new construction projects and the expansion of agricultural fields.

Fig. 45. Location of two tombs discovered during the construction of a house beyond the traditional delimits of Chichim village. Photo and notation courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 46. Location of a cist tomb opened during the expansion of agricultural lands, Chichim. Photo and notation courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 47. A close-up of the cist burial in fig. 46. Note how the walls and roof of the tomb are lined with stone slabs, which may have been roughly hewn into their present shapes. Photo and notation courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 48. Three cylindrical amber-colored agate beads. The smallest bead is made of carnelian. These beads were removed from inside the cist tomb in fig. 47. These types of beads are common in the Tibetan world where they are widely traded. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 49. Cord-marked ceramic fragments picked up in the vicinity of the cist burial in fig. 47.

Fig. 50. Various ceramic fragments and ceramic spindle whorl collected around Chichim village. Some of these sherds may be from mortuary vessels. The whorl may have come from the grave of a female.

Fig. 51. This stony mound may mark the location of a tomb, Chichim. Such tumuli may be associated with cist burials. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

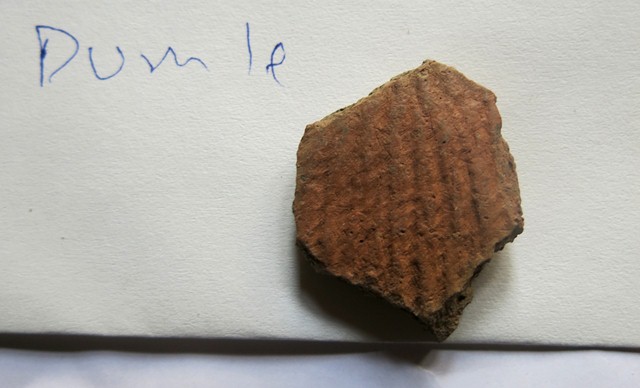

Fig. 52. A single fragment of a cord-marked redware vessel of the type deposited in tombs in Spiti. This ceramic sherd came from the settlement of Dumle.

Fig. 53. An assortment of earthenware sherds collected in Rangthang. The wheel-turned painted pottery and other fragments in the upper row are from more recent types of ceramic vessels. The cord-marked fragment of buffware on the right side of the middle row may be a mortuary ceramic.

The two sherds of painted pottery on the left side of the upper row are particularly noteworthy. Presumably, the dark red color is from paints containing significant quantities of iron oxides. These ceramics are comparable to painted pottery from lower Ladakh, which is also decorated with straight lines running parallel or with a series of curving lines painted in dark red.* However, the paste used to make the painted ceramics found in Spiti and Ladakh appears to be of a different composition (this might be indicative of different periods of production). Howard (ibid.) describes the Ladakh vessels as having a ground color ranging from biscuit to dull orange, whereas the sherds from Rangthang are brick red in color. Based on the architecture and history of fortresses standing in the vicinity of the ceramic finds in lower Ladakh, Howard (ibid.) hypothesizes that this painted pottery dates to the early and middle phases of the kingdom period (circa 1000 to 1600 CE).

See Howard, N. 1995: “Ancient Painted Pottery from Ladakh”, in Ladakh: Culture, History, and Development between Himalaya and Karakoram. Recent Research on Ladakh 8: Proceedings of the Eighth Colloquium of the International Association for Ladakh Studies held at Moesgaard, Aarhus University, 5-8 June 1997, Oakville (eds. M. van Beek / K. B. Bertelsen / P. Pedersen). Aarhus University Press. In his article, Neil Howard also provides a general introduction to what was known about ancient ceramics in Ladakh in the early 1990s. On the painted pottery of Ladakh, also see Francke, A. H. 1905: “Archaeological notes on Balu-Mkhar in western Tibet” in Indian Antiquary. A Journal of Oriental Research, vol. 34, pp. 203–210 + 9 pp. of plates. Bombay.

Fig. 54. Various ceramic fragments collected in Key village. The finer-textured greyware sherds in the lower two rows appear to represent historical era ceramic types.

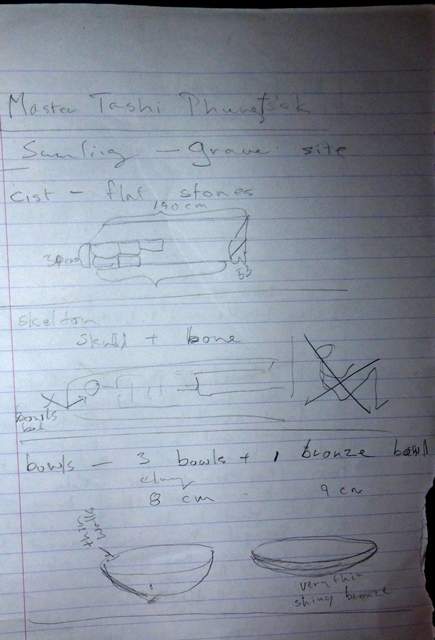

Two tombs have also been documented in Sumling village. The village headmaster told the SRAHS that when digging the foundation for a school building in 1998 they stumbled upon a tomb. Apparently, a remaining stone wall of the burial chamber was incorporated into the foundation of the school. The laborers working on the site discarded bones from the tomb including a human skull. Three clay bowls and a shallow bronze bowl were recovered from the burial at Sumling. Another tomb was unearthed in 2001 or 2002 when a latrine for the school was being constructed. This tomb is described as having had a stone roof.

Fig. 55. A sketch of tomb architecture, interment and objects discovered in Sumling in 1998. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 56. The current location of tomb in fig. 55. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 57. The site of the tomb near the school latrine, Sumling. Apparently nothing remains of this burial structure today. Photo courtesy of SRAHS.

Fig. 58. Ceramic fragments picked up in Sumling. The two cord-marked sherds may well have come from local tombs.

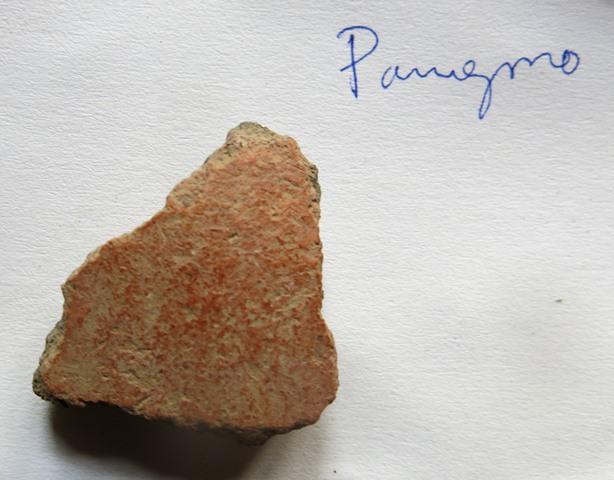

Fig. 59. Ceramic fragment collected in Pangmo (sPang-mo) village.

Fig. 60. Cord-marked sherd collected in Hanse (Han-se). This ancient fragment may have been deposited in a mortuary context. Note the white encrustation on the surface of this ceramic. These depositions on pottery usually contain carbonates (CO₃).

Fig. 61. Pottery sherds from Losar, the uppermost village of Spiti. The typological characteristics of these more recent ceramics are as yet unclassified.

Fig. 62. Fragments collected in Sumra (Sum-ra), a village in Kinnaur on the opposite side of the Spiti river from the lower villages of Hurling and Lari. These ceramics appear to be closely related to examples with funerary functions presented in this article.

An analysis of the cultural, technological and chronological characteristics of ancient burials in Spiti

In order to better understand the cultural, technological and chronological traits of grave goods in Spiti, I will compare them to those from adjoining regions. The biggest impediment to any comparative exercise is the unsystematic collection of mortuary materials in Spiti. Moreover, the objects reviewed above represent a small fraction of the assemblage of grave goods uncovered in recent years, the true extent and composition of which is unassessable. What has been obtained often lacks a provenance and a stratigraphic context and is weighted towards objects without appreciable market value. Compounding the inherent difficulties in studying highly fragmentary groups of objects is the absence of chronological controls.

The following categories of objects will discussed:

- Shells

- Musk deer tusks

- Patterned chalcedony beads

- Ceramics

- Metalware

- Other tomb appointments

Fig. 63. Perforated shell disc from Lippa, Kinnaur. Photo credit: Mukherjee et al. 2015, p. 12 (fig. 5).

- Shells

Spiti notwithstanding, shell (Turbinella pyrum) discs with a perforation in the center have been recently discovered at three different burial sites in the Indian Himalayan states of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh (see Mukherjee et al. 2015). These discs are between 1.9 cm and 3.8 cm in diameter. One such disc was removed by archaeologists from a so-called cave burial in the Central Himalayan site of Malari, Uttarakhand (tomb dated to circa 100 BCE to 100 CE). Spouted red and black pottery, gold mask, gold pendent, iron tools, beads, and the complete skeleton of a yak hybrid were also present in the Malari tomb. Two shell (Turbinella pyrum) discs with a central perforation were discovered near a tomb excavated in Lippa, Kinnaur.* A shell disc with a central perforation and 13 shell beads contained inside a long-necked ceramic vessel (one of 18 vessels) were recovered from a tomb inadvertently opened in the Kinnauri village of Ropa (Nautiyal et al. 2014).

Other contents of this cist tomb included iron implements, copper bangles, pottery and beads of steatite and charcoal, as well as animal and human remains. This cist burial and others in the villages of Lippa and Kanam have been dated to the middle of the first millennium BCE. See Nautiyal, V. /Bhatt, R. C. / Saklani, P. M. / Mushrif Tripathy, V. / Nautiyal, C. M. / Chauhan, H. 2014: “Lippa and Kanam: Trans-Himalayan cist burial culture and pyrotechnology in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, India”, in Antiquity, vol. 88, no. 339, 5 pp. For more on this paper, see April 2014 Flight of the Khyung. Turquoise, agate and carnelian beads were also recently discovered by archaeologists in Kinnauri burials. Human remains from the burials of Lippa and Kanam are now undergoing osteobiographical analysis. See Mushrif-Tripathy, V. / Nautiyal, V. / Bhat, R. C. / Saklani, P. / Chauhan, H. Forthcoming: “Osteobiographical studies on Lippa-Kanam in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, India”, in Lakshna Lecture Series, Himachal State Museum.

According to Mukherjee et al. (2015), the ancient shell discs of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh were probably used in conjunction with stone beads or sewn on clothing. These objects could have been obtained from north Indian sites such as Agroha but may have been modified locally (ibid.). The deposition of shell discs in the burials of Malari, Kinnaur and Spiti reflect their socioreligious significance and importance as items of exchange, value and status (ibid.).

Perforated shell discs and perforated cowrie shells have been found in the burial caves of Chokhopani, in the Mustang district of Nepal.* The burials of Chokhopani have been dated to the first half of the first millennium BCE. The Chokhopani cowries are perforated near the narrow end of the shell, while the cowries of Gyu (see figs. 3, 4) were pierced in the middle of the shell. Suspended from a string, the cowries of these two respective regions would hang differently, which is suggestive of variable forms of ornamentation (for more on ancient cowries, see May 2014 Flight of the Khyung).

See Tiwari, D. N. 1984-1985: “Cave Burials from Western Nepal, Mustang”, in Ancient Nepal. Journal of the Department of Archaeology, no. 85, pp. 1–12 (+ 8 pp. of plates). Also see Simons, A. / Schön, W. / Shrestha, S. S. 1994: “Preliminary Report on the 1992 Campaign of the Team of the Institute of Prehistory, University of Cologne” in Ancient Nepal. Journal of the Department of Archaeology (ed. K. M. Shrestha), no. 136, pp. 51–75. Kathmandu.

The discovery of objects made of shell in the burials of Gyu and other Himalayan regions can be used to posit trade links over a wide swathe of the northern Indian Subcontinent. The ultimate origin of these shells is the Indian Ocean, presupposing the existence of a web of trade extending from its shores to various Transhimalayan regions (cf. Mukherjee et al. 2015). Perforated shell discs have been discovered at Iron Age sites in both south and north India (ibid., 13). We might view the northern sites as nodes arrayed along a trade network encompassing Himalayan and Tibetan plateau regions. The discovery of shell discs in Mustang, Malari and Kinnaur suggests that these materials arrived in high mountain tracts along lines of trade branching out in various directions from centers of production and distribution in tropical Indian. Perforated shell discs may have reached Spiti directly from Kinnaur but this was a latter stage in the transfer of shells over a distance of no less than 1500 km.

It is worth considering that Spiti may have functioned as a transshipment point for the distribution of shells from cis-Himalayan regions to western Tibet and beyond. Cowrie shells of Indian Ocean origin enjoyed extremely wide distribution in ancient times: they have been discovered in tombs in Central Tibet and further afield in Mongolia. Like in Kinnaur, cowries may have been used in Spitian and Central Tibetan burials of the Iron Age, but this remains to be corroborated.

As noted, the custom of depositing worked shell discs in burials was widespread in the Indian Subcontinent of the Iron Age. This funerary custom attests to the great popularity of shells as ornaments with decorative and probably talismanic functions as well. From their distribution, it can be seen that the use of worked shell discs transcended many cultural, linguistic and geographic barriers. Peculiar regional traits, however, may well be indicated, distinguishing Spitian shell ornaments from those of other regions. The burials of Gyu demonstrate that the local shell repertoire included discs, buttons, cylinders, a star, perforated cowries and other types. Particular features of these objects such as engraved lines arrayed in a radial pattern and the arrangement of perforations seem to differentiate them from other groups of shell ornaments.

The presence of at least three species of marine gastropods in Spiti modified in a variety of ways by artisans reflects the cultural and economic importance of these materials. It appears that shell ornaments in Spiti (and Kinnaur) were deposited in tombs with the intention that they would be used by the deceased in the afterlife. Tibetan literature specifies a variety of objects as provisions for the dead, including ornaments of various kinds.* Tibetan archaic funerary rites also mention sundry objects used as tabernacles for the soul of the deceased during evocation rites and as apotropaic instruments for warding away infernal demons.†

For a list of these provisions, see my 2008: Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. pp. 448–451. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Ornaments in this list include turquoise (mtsho-ro), patterned agates (gzi), and banded and plain agates (mchong).

In an archaic origins myth set in Upper Tibet in the cycle of funerary rituals known as Mu cho’i khrom ’dur (began to be compiled in the 11th century CE), one of the prized possessions of two children, along with a gold ring and silver mirror, is a white conch shell bracelet (gdub-bu). These three objects serve as prime symbols of well being for both the living and the dead. In the text Klu ’bum nag po (composed circa 10th century CE) the three main funerary instruments of priests (gshen) are a drum, flat-bell and white conch. In another archaic origins myth, white conch is one of nine objects owned by an archetypal female who furnishes them for the performance of the bird wing funerary ritual of liberation. For these textual references, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 434, 477, 480, 481. Soteriological functions of white shells in the Tibetan textual tradition are probably related to their lustrous white surface, hardness and the auditory qualities of integral specimens. Similarly, in Tibetan archaic funerary rites white strips of cloth are used to guide the soul of the deceased.

- Musk deer tusks

Also in the burials of Gyu were four upper canines or tusks of the male musk deer (see figs. 3, 4). These four enlarged canines seem to form two pairs. Like white shells, these objects are likely to have had both decorative and talismanic value. However, unlike sea shells, musk deer occur in Himalayan regions adjoining Spiti. I would think that moschids once ranged in Spiti as well, especially before wholesale deforestation struck the region. Musk deer tusks, as coveted objects, may have been added to necklaces or worn as pendants by the living. As with shells, their deposition in tombs is probably related to funerary ritual activities as well as use by the dead as provisions in the afterlife.

The musk deer is one of a number of animals in the Old Tibetan language text rNel drĭ ’dul ba’i thabs sogs, where it functions as a tabernacle or vehicle for the dead during the perilous passage to the afterlife (Bellezza 2013: 122). In another Old Tibetan funerary ritual text entitled Sha ru shul ston rabs, “musk deer” (gla) appears to form part of the name of the mother of the first sacrificial deer for the dead (dri-sha; ibid., 200) The protective function of musk deer tusks (gla-ba’i mche-ba) is noted in a ritual text for the Zhang Zhung god Phu-wer.*

See Bellezza 2005, p. 373: Calling Down the Gods: Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet. Leiden: Brill.

Musk deer tusks have been also discovered in the burial caves of Chokhopani, Mustang (Tiwari 1984-1985). According to this author, these tusks were used in necklaces.

- Patterned chalcedony beads

Many patterned and banded agate and carnelian beads have been discovered in ancient burials and other contexts in tropical India, Himalayan regions, Afghanistan, Western Asia and Southeast Asia. Chalcedony beads were among the most common types of ornamentation in ancient Asia. However, very few sites in and around Tibet from where such materials were discovered have been studied scientifically. The looting of beads from tombs in recent years (especially in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nepal) has reached epidemic proportions.

The stunning patterned agates from Gyu (see figs. 5, 6) are of a distinctive genre, associated with Tibetan and greater Himalayan regions extending west to Afghanistan. Presumably it is somewhere in this wide region that the beads of Gyu were made. The circulation of these kinds of beads in greater Tibet for centuries signals that some may be of native manufacture. The high quality specimens from Gyu might even be attributable to local sources, authentic examples of patterned agates produced on the western Tibetan plateau or Himalayan rim-land (perhaps even in Spiti itself). Other types of patterned agates, natural and manufactured, were probably imported onto the Tibetan plateau in ancient times. Further investigation is required to pinpoint the origins of zi beads.

The genre of patterned chalcedony represented in the Gyu burials are characterized by varying degrees of translucence, bold designs created with thick white lines, barrel and cylindrical shapes tapering towards the ends, and flattened ends. These can be contrasted with other genres of patterned chalcedony beads exhibiting more advanced lapidary techniques also associated with Tibet. These genres are characterized by opaqueness, high contrast between the ground and decorative motifs, highly refined designs, and ends that tend to be more rounded or beveled. The zi exhibiting such traits are clearly among the most advanced stone beads produced in the ancient world.

The banded zi bead recovered from a tomb in Gungri (see fig. 27) is also of a type associated with Tibet. Similar beads are reported from Afghanistan, but the Gungri specimen appears to be a genuine example of ancient Tibetan or cis-Himalayan technological capabilities.

A zi stone was discovered by the Chinese archaeologist Tong Tao in a tomb at the Chuthak (Chu-thags) site in Guge, western Tibet.* This tomb is believed to be around 1800 years old (if the bead was an heirloom it could be considerably older than the burial). Wooden combs, bronze mirrors and weaving items were deposited in the same Chuthak burial, suggesting that the occupant was female. The Chuthak zi bead is 2.85 cm in length and has a brown ground and white markings. There are no published images of the Chuthak bead yet, but thanks to my Chinese colleagues, I have been able to view a photograph of this patterned agate. It is of a type known as ‘horse tooth’ (rta-so), with a thick, brown zigzag stripe wrapping around the middle of the bead.

See the Yibada website article: “Archaeologists Find Ancient Beads in Tibet”

http://en.yibada.com/articles/19320/20150313/archeologists-ancient-beads-tibet.htm

For a Tibetan version of the article and a picture of the zi bead falsely attributed to Chuthak, see the Himalaya Bon website:

http://himalayabon.com/news/2015-04-10/574.html

The Chuthak bead with its translucence, flattened ends and coarser decorative treatment is comparable esthetically and technologically with the Gyu cache. Therefore, the Chuthak bead can also be attributed to Tibetan and greater Himalayan regions extending west as far as Afghanistan. The shared qualities of the Gyu and Chuthak zi beads are mirrored in other categories of material objects, namely the ceramics and rock art of Spiti and Guge.

Even with the extremely limited data now available to us, it is clear that a large variety of artificially created patterned and banded chalcedony beads were used on the western portion of the Tibetan plateau. These beads are a tribute to the craftsmanship and technological capabilities of the greater region in pre-Buddhist times. It is remarkable that the lore and allure of these beads remains as strong today as ever.

In Tibetan ritual literature, zi and banded agates known as chong (mchong) are often associated with the watery realm and the subterranean spirits known as lü (klu). For example, the appearance of deities like the King of the Water Spirits and the goddess of Lake Nam Tsho (gNam-mtsho) are described using these materials. In rituals of propitiation necklaces of zi and chong are sometimes offered to elemental goddesses such as the men (sman). Of special interest is reference to patterned chalcedony (gzi) and banded chalcedony (chong; Classical Tibetan = mchong) in the Old Tibetan funerary manuscript Pt 1194, which was written around 1200 years ago (see Bellezza 2008: 506–510). In this manuscript these types of stones are among nine objects used to ornament and empower bird wings used ritually to liberate the deceased from infernal bonds. These precious stones provide pathways of illumination for the dead as they make their way towards the afterlife. Through direct correspondence or associative links, Pt 1194 provides us with some insight into the why zi and chong stones were deposited with corpses in the pre-Buddhist burials of Spiti and western Tibet.

- Ceramics

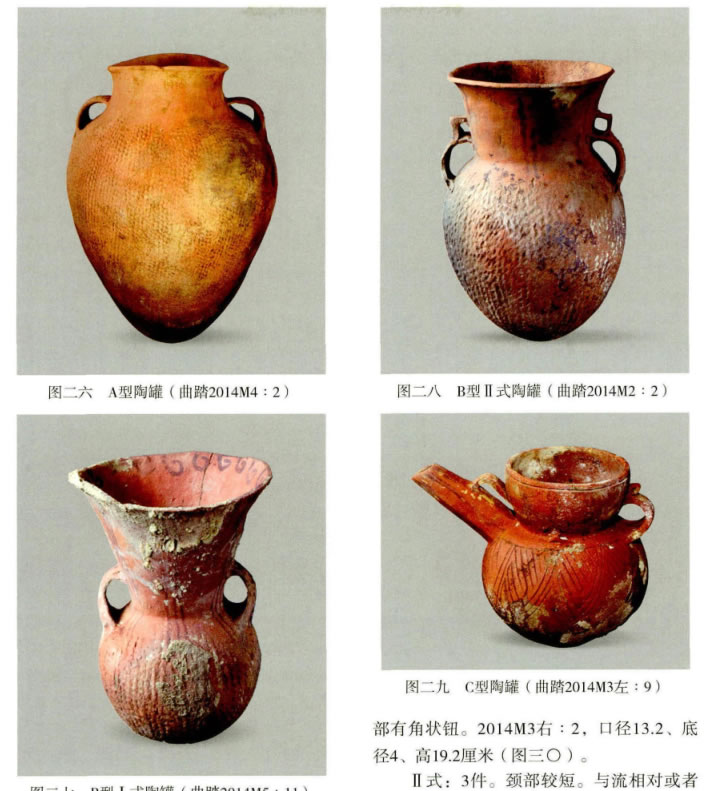

The most abundant and durable class of grave good in Spiti, as in many other places in the world, is ceramic vessels. Although a detailed analysis of the techno-typology of Spitian ceramics is beyond the scope of this article, their more obvious qualities will be examined in this section. Jars with ellipsoidal and globular bodies and lug handles as well as shallow bowls are the most common forms discovered to date. These vessels are reddish, greyish and brownish in color, rough textured and often with cord or fabric markings. In terms of their form, decorative treatment and paste, these ceramics bear strong similarities to mortuary vessels from burial sites in Guge, western Tibet. There are also affinities between the mortuary ceramics of Spiti and those from Kanam (Himachal Pradesh) and Ladakh, as well as somewhat weaker ties to Malari (Uttarakhand) and Mustang (Nepal).

It is not yet known how mortuary ceramics were used or deposited in the tombs of Spiti. It is likely that at least some vessels may have been employed in the storage of food provisions for use by the dead during the journey to the otherworld. In some cases, ceramic vessels may have been subjected to fire during the cooking of foodstuffs before burial. Other ceramic vessels may have been part of funerary rituals with nonnutritive functions or domestic vessels repurposed for funerals.

The comparative analysis of ceramics that follows is based on a visual appraisal alone, not on qualitative methods of analysis. It is further limited by the small number of images of ceramics available to me. As the study of ancient ceramics picks up pace in Spiti, optical microscopy, X-ray diffraction, spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy, etc. could be employed in order to determine mineralogical and microstructural composition. Analyzing the chemical makeup of clay minerals and inclusions and determining firing conditions, etc. is crucial in determining the provenance and technologies exploited in the production of ceramics, the basis for more precise methods of comparative analysis.

Fig. 64. Large bulbous cord-marked jar with flaring neck and two lug handles fixed to the upper body and middle portion of the neck (34 cm in height). The blackened lower portion of the vessel seems to indicate that it was once put on a fire. Gurgyam, Upper Tibet, dated to circa 220–350 CE.

This vessel was excavated from a tomb in Gurgyam (Gur-gyam), Gar (sGar). It was one of several ellipsoidal and globular jugs and cylindrical beakers discovered in the same Upper Tibetan tomb. Other grave goods included wooden objects (circular container, tray, etc.), cane items, metal objects (copper and copper alloy bowls, gilt metal fragments, iron pin and spearhead, etc.) and textiles (silk brocade and taffeta, woolen serge). A human femur from the Gurgyam inhumation has yielded a calibrated date of circa 220–350 CE (see October 2010 Flight of the Khyung).*

Between 2012 and 2014, Chinese archaeologists excavated a total of 11 tombs at Gurgyam. Eight of these tombs date to the Protohistoric period (called the “Zhang Zhung period” by the archaeologists) and three from the imperial period (circa 630–850 CE; Chinese call this the “Tubo period”). The Protohistoric period burials have been scientifically dated to the 3rd and 4th centuries CE They consist of cists set several meters below the surface and some of them contained wooden coffins and wooden supports for the stone roof. The Protohistoric tombs were characterized by multiple secondary burials, whereby the bones of the dead were collected and specially deposited. The variety of grave goods and use of wood (a relatively scarce resource in the region) indicate that those interred were of a higher social ranking and may have belonged to the local nobility. The Imperial period cist tombs made with stone slabs were of more modest proportions and contained corpses in the flexed position. Fewer grave goods were deposited in the Imperial period tombs, but quantities of glass beads were recovered from them. See op. cit. Chinese Archaeology. 2015: “New Discoveries at Gurugyam Cemetery and Chu vthag Cemetery in Ngari, Tibet”, in Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (IA CASS) (trans. Tong Tao), April 10, 2015:

http://www.kaogu.cn/en/Special_Events/Top_10_Archaeological_Discoveries_in_China_2014/2015/0410/49819.html

According to Dr Tong Tao (personal communications), a detailed report about the Gurgyam and Chuthak burial sites will appear as a book in about two years. The more rudimentary tombs in Gurgyam with fewer grave goods of the Imperial period indicate that more simplified burial rites prevailed in that time, perhaps as a result of social and economic decline caused by the Tibetan conquest of Zhang Zhung in the early 600s CE. Environmental degradation may also have been an important factor in the diminution of provisions made for death. Burials lined with stone slabs dating to the Imperial period also have been documented west of Lake Dangra, in the central Changthang region of La-stod lho-ma (see Bellezza 2008, pp. 127, 128). On the tombs of Upper Tibet also see my 2014: Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Ceremonial Monuments, vol. 2. Miscellaneous Series – 29. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza, 2011).

The Upper Tibetan vessel from Gurgyam is strikingly similar in form and decorative treatment to one discovered in the Spitian village of Mani Gongma (see supra, fig. 14). The main differences between them are their superficial color and cord marking. The Gurgyam vessel is red and its surface impression irregular, while the Mani Gongma one is buff in color with linear marking. The differences in coloration are probably due to the chemical composition of local clays and possibly also because of the kilns and methods of firing used. The existence of a cognate vessel type in a tomb at Mani Gongma can be used to provisionally date it to the same time period as the Gurgyam example (3rd or 4th century CE).

Fig. 65. A smooth-walled globular jar with flaring neck and strap handle (12 cm in height) discovered in the same Gurgyam burial as fig. 64.

As we have seen, smooth-walled buffware and greyware sherds have been discovered in Spiti and comparison with the Upper Tibetan vessel can be made.

Fig. 66. Assorted ceramic vessels from a Guge mortuary site dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE. Photo credit: PowerPoint presentation of Tong Tao, International Conference of Shang Shung Cultural Studies Beijing, September 18–21, 2015.

Fig. 67. Four ceramic vessels discovered in the Chuthak burial grounds in 2014. These burials have been estimated by Chinese archaeologists to date to circa 250 BCE to 300 CE (calibrated dates have not yet been released). Top left: cord-marked amphora; top right: cord-marked ellipsoidal jar with flaring neck, wide mouth and strap handles surmounted by small ancillary handles; bottom left: cord-marked bulbous jar with long, flaring neck, extremely wide mouth, pair of strap handles and painted volutes around the interior of the rim; bottom right: spouted globular jar with incised geometric decorations on the body and single handle with thumb rest. Photo courtesy of Institute of Archaeology, CASS and Tibetan Institute of Antique Conservation (Xizang Zizhiqu Wenwu and Baohu Yanjiusuo).

Cord-marked ellipsoidal and globular jars have also been unearthed in the central Guge burial sites of Dungkar-Piyang (Dung-dkar Phyi-dbang) and Gebusailu. These sites are dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE.* Some of the vessels from Chuthak, Dungkar-Piyang and Gebusailu have forms closely related to the ellipsoidal and globular jars of Gurgyam and Spiti, but taken as a whole there are significant differences between them, which appear to be indicative of changes in the styles of mortuary vessels in western Tibetan that occurred during the Iron Age and Protohistoric period. My initial assessment (pending more information) is that over time the mortuary ceramics of the region became less diverse and more simplified in form. Socioeconomic conditions do not appear to be a major factor because prestige objects such as imported silk brocade were collected from the Gurgyam tomb discussed above well as from the Chuthak burials (e.g., golden burial mask; see November 2013 Flight of the Khyung). Gurgyam and Chuthak are both in Guge (as Eternal Bon literary sources indicate), so vernacularism can also be discounted as a factor in explaining differences in the ceramics assemblages of these two sites. This is corroborated by the fact that Chuthak is roughly equidistant to Spiti and Gurgyam, yet it is the two outer sites that have cognate ceramic vessels.†

See Chinese Institute of Tibetology, Sichuan University. 2001a: “Trial Excavation of Ancient Tombs on the Piyang-Donggar Site in Zanda County, Tibet” in Kaogu, no. 6, pp. 14–31.

Chinese Institute of Tibetology, Sichuan University. Beijing. 2001b: “Survey of Gebusailu Cemetery in Zanda county” in Kaogu, no. 6, pp. 32–38. Beijing.

Yao Jun. 2004: “An Observance and a Preliminary Research on the Pottery Craft of Western Tibet” in Essays on the International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, pp. 70–97. Chengdu: Sichuan Remin Chuban She.

Five shaft tombs in a line along a hillside were excavated in Chuthak. The shafts or passageways of these tombs were around 5 m in length and sealed off in the middle by a stone plate. In each tomb there were one or two burial chambers with arched entranceways. Each burial chamber contained a wooden coffin and an array of ceramic vessels in close proximity. Inside each coffin was a single corpse in the flexed position as well as some grave goods. Copious amounts of horse, sheep and goat bones were deposited in the burial chambers. Grave goods in Chuthak included, “painted wooden trays, square wooden combs, handled bronze mirror, carved wooden plaques, wooden waving implements, rectangular wooden trays, rattan utensils, painted potteries and plentiful glass beads.” See op. cit. Chinese Archaeology. 2015: It is interesting to note that cornflower blue glass beads like those from Chuthak illustrated in ibid. are still in circulation as heirlooms in Tibet.

The jars with a bridge over the spout of central Guge burial sites, a highly distinctive form, have counterparts in spouted jars discovered in a Gurgyam burial in 2013 and in the Malari burial (see December 2013 Flight of the Khyung). These spouted jars straddle both sides of the Himalaya and the chronological divide between the Iron Age and Protohistoric period.

From the evidence at hand, we can conclude that earthenware vessels remained a common mortuary accompaniment in western Tibet for five or more centuries, overlapping the Iron Age (600–100 BCE) and Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE).

Fig. 68. Wide-mouthed globular jar with brownish exterior, short neck, two strap handles, rounded spout, and cord-marked treatment. This vessel was discovered in the “Kaerbu” (Tibetan = Mkhar-bu?) cemetery, Guge, Western Tibet. Probably Iron Age. Tibet Museum collection.

In Spiti, spouted mortuary vessels are represented by a buffware globular jar procured in Tashigang (see supra, fig. 41)

. The Spitian vessel has a similarly shaped strap handle and is cord marked. However, its mouth is constricted and the spout much more pronounced than the Kaerbu jar.

Fig. 69. Ceramic vessels from burial sites in Kanam: A ) smooth-walled jar with broad shoulder and somewhat flattened body that tapers inward towards base, biscuit colored fabric, flaring neck and pair of strap handles attached to top of the body and top of the neck; B) smooth-walled globular jar of redware, with slightly flaring neck and pair of strap handles attached to the top of the body and top of the neck; C) globular jar with loop handle, spout, short collared neck and everted rim; D) redware jar with flat base, barrel-shaped body, flaring neck and very wide mouth. Photo credit: J. S. Rawat in Nautiyal et al. 2014.

Jars A and B have many of the same attributes as the jar from Mani Gongma in fig. 14. There are however some notable differences. The bodies of the two jars from Kanam are smooth-walled and circumscribed by parallel lines. The strap handles are also much larger than the lug handle of the Mani Gongma jar. Counterparts of the other two jars from Kanam illustrated in fig. 68 have not been documented in Spiti.

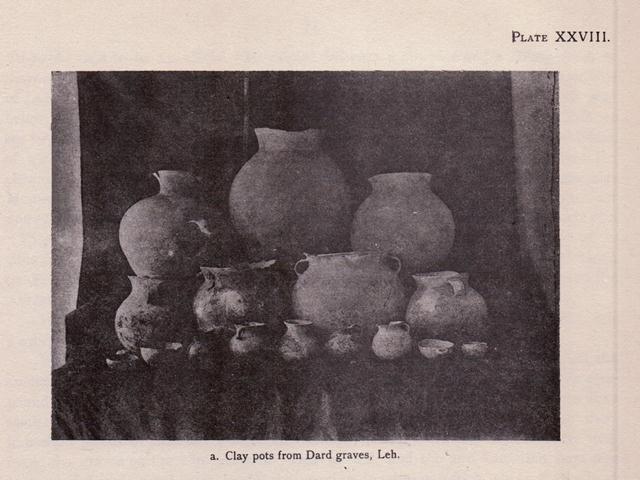

Fig. 70. Ceramics collected from tomb in Teu Serpo (Te’u gser-po), in the Ladakh valley. These vessels are attributed by A. H. Francke to the first half of the first millennium CE (Tibetan Protohistoric period). Photo credit: Shawe, in Francke 1914, fig. XXVIII, a.

The ceramics from Teu Serpo were excavated by A. H. Francke and associates on two different occasions (1903 and 1909).* Francke describes a cist tomb, the burial chamber measuring approximately 2 m x 1.5 m x 2 m. The stone members used in construction were around 1.5 m in length. The stone roof of this tomb was set more than 1 m below the ground surface. In addition to at least 17 relatively intact ceramic vessels illustrated by Francke, there were various fragments in the tomb. The largest ceramic vessel found in Teu Serpo was in pieces but Francke estimates that originally it was almost 1 m in height. Human bones were deposited inside some of the vessels, an ancient custom reported by informants in Lahul-Spiti and western Tibet as well. This indicates that corpses were defleshed and otherwise treated to separate the bones, a form of disposal known as excarnation. According to Francke, the skulls interred in the Teu Serpo burial were dolichocephalic (long-headed) in character. Tombs explored by Francke in Ladakh are generally referred to him as Dard graves. Francke believed that the Dards were the inhabitants of Ladakh before the arrival of Tibetan peoples, but the simple replacement of one people by another is not supported by much subsequent research.†

See Francke, A. H. 1914. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Part 1, Personal Narrative, pp. 71, 72. Reprint, Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series, vol. 38., S. Chand, 1994.

See the following works:

1) June 2013 Flight of the Khyung.

2) Howard 1995, pp. 225, 232, 233.

3) Denwood, P. 1995: “The Tibetanization of Ladakh – The Lingusitic Evidence”, in Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia (eds. H. Osmaston and P. Denwood), pp. 281–289. London: The School of Oriental and African Studies.

4) Denwwod, P. 2005: “Early Connections between Ladakh/Baltistan and Amdo/Kham” in Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives (ed. J. Bray), pp. 31–39. Tibetan Studies Library, vol. 9. Leiden: Brill.

5) Bruneau, L. and Bellezza, J. V. 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf

The globular jars of Teu Serpo come in a variety of sizes and forms. They appear to be smooth-walled and are not painted (unlike some other grave pottery studied by Francke). These vessels tend to have shorter and straighter necks than the vessels of Spiti and western Tibet thus far documented. Generally speaking, the Teu Serpo jars are also more spherical than those of Spiti and western Tibet. Some Teu Serpo specimens have flange-like rims. The forms of the Teu Serpo vessels are reminiscent of certain Central Asian examples.

Moving further afield, the forms of ceramics discovered in the Malari tomb bear less resemblance to the ceramic assemblage of Spiti.* The globular jar closest in form to the one from Mani Gongma (supra, fig. 14) has wavy lines painted in black, an inflected body and handles in a different style (Bhatt et al. 2008-2009, fig. 6). A greyware jar with globular body, short neck, wide mouth and fairly broad flattened rim (Bhatt et al. 2008-2009, fig. 13) is also fairly close in form to the jar in the background of supra, fig. 39. However, unlike the Malari jar, the Spitian example is cord-marked and with a vertical rim. Globular jars with single strap handles attached to the middle portion of a short neck with slightly everted rim in Mustang (Tiwari 1984-1985, pl. 2, b, c) are also related to the mortuary ceramics of Spiti. Close correspondences between the vessels of Spiti and Mustang is limited in scope to this one example.

See Bhatt, R. C. / Kvamme, K. L. / Nautiyal, V. / Nautiyal, K. P. / Juyal, S. / Nautiyal, S. C. 2008-2009. “Archaeological and Geophysical Investigations of the High Mountain Cave Burials in the Uttarakhand Himalaya”, in Indo-Kōko-Kenkyū – Studies in South Asian Art and Archaeology, vol. 30, pp. 1–16.

The ellipsoidal mortuary jars of Spiti and Gurgyam are the closest in form and decorative treatment to all of the vessels compared above. They also appear to have closely matching coarse-textured fabrics. These vessels indicate that the adjacent regions of Guge and Spiti possessed funerary rites with some material components closely related to one another. This comes as no surprise when examined against the rock art of Spiti and Upper Tibet: they share significant stylistic and thematic elements in common (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung). In light of the rock art records, we might hypothesize that the funerals of Spiti and Guge not only relied upon similarly designed pottery but also shared an ideological groundwork pertaining to eschatological traditions and funerary ritual dispensation.*

Interestingly, both Guge and Spiti have the same class of ancient priests known as jowa (jo-ba). It is not known, however, how long priests by that name have been active on the western Tibetan plateau. See “The triumvirate of ancient ritual practitioners in Spiti”, in Flight of the Khyung, June 2015.