August 2014

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to the eighth anniversary issue of Flight of the Khyung! Thanks very much for your interest and patronage. It has taken quite a bit longer than usual for this month’s newsletter to appear, but the khyung is back on track after a bout of stormy weather. A series of engaging subjects are planned for the issues to come, and these should appear in fairly quick succession.

I would like to begin this month’s offering with an announcement for my newest book, which was published in August, 2014:

The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World

2014: Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham, Maryland; London, United Kingdom

ISBN 978-1-4422-3461-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4422-3462-8 (electronic)

This groundbreaking book provides a new and vital perspective on the culture and history of Tibet. Drawing on three decades of research and exploration, the author recounts the discovery of an ancient civilization on the most desolate reaches of the Tibetan plateau, revolutionizing our ideas about who Tibetans really are. While we now equate Tibet with Buddhism, it was once a land of warriors and chariots, whose burials included megalithic arrays and golden masks. This first Tibetan civilization was a cosmopolitan one with links extending across Eurasia, bringing it in line with many of the major cultural innovations of the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age. The Dawn of Tibet presents a broad range of archaeological, textual, and ethnographic materials collected and analyzed by the author over the course of his epic journeys. His book describes the vast network of castles, temples, megaliths, necropolises, and rock art established on the highest and now depopulated part of the Tibetan plateau once inhabited by an ancient culture and people known as Zhang Zhung in Tibetan texts. Bellezza relates literary tales of priests and priestesses, horned deities, and the celestial afterlife to the actual archaeological evidence, providing a fascinating perspective on the origins and development of a civilization that flourished long before Buddhism took root in Tibet.

Ancient Tibetan Bridle Finally Sees the Light of Day

While treading the passageways of Old Lhasa more than a decade ago, an itinerant dealer offered to sell me an ancient horse bridle. Unsolicited, he pulled it out of a sack to show me. I was immediately struck by the cultural and historical importance of this copper alloy artifact (see account in my book Zhang Zhung, pp. 546–548; bibliographic details are found in the “Books” section of this website). Thanks to the support of a couple of friends doing aid work in Tibet, I was able to purchase and then donate this horse bridle of thirty-five separate components to the Tibetan Provincial museum. The bridle was kept in storage until recently when the newly refurbished and expanded museum reopened its doors to the public. The bridle now enjoys a prominent place among the “Pre-Tubo Kingdom” exhibits. “Pre-Tubo Kingdom” is a Chinese attribution, which corresponds to the Iron Age (circa 600–100 BCE) and the Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE). Interestingly, this huge span of time is the most poorly represented in the Tibetan Provincial museum. Holdings only consist of a small handful of silver and copper alloy objects. In the months to come, this newsletter will be taking readers on a virtual tour of some of the museum’s priceless artifacts.

According to the Tibetan dealer who sold it, this group of objects making up a horse bridle was recovered from a tomb in Nagchu prefecture. When obtained, a tiny fragment of the leather throng used to thread the various components together was still embedded in one piece of the bridle. Unfortunately, this speck of leather did not survive the pretreatment process to prepare it for AMS dating. Presumably, this Tibetan-made bridle was deposited in a tomb as part of an array of articles related to the psychopomp horse (do-ma), which figures prominently in funerary rites recorded in Old Tibetan language texts. In the close-up image, the various components of the bridle are clearly visible: coverlids, joints, cheekpieces and two-part mouthpiece. The two large, slightly curved plates appear to be phalerae used to ornament the horse harness. Their position in the restrung bridle probably does not reflect their original placement in the harness.

Horned, Feathered and Sanctified: Extraordinary anthropomorphs in the rock art of Upper Tibet –

Part 1

Introduction

The human figure is of course one of the most evocative subjects in art. We readily respond to what is like us, however different the time, circumstances and cultural setting may be. In the extensive rock art of Upper Tibet, there are petroglyphs and pictographs of anthropomorphic figures in a large variety of contexts. Among the most intriguing are those that seem to embody mythic, divine, ritual and elite social qualities, as opposed to humans who conduct the relatively mundane business of hunting and herding. I use the somewhat awkward term ‘anthropomorph’ to signify human figures depicting both mortals and nonhumans such as mythic and divine personages.

The identity of the anthropomorphs portrayed below is an engaging question to which there are few definitive answers. Differentiating, say, masked priests from theriomorphic spirits, or shamans from mythic heroes is very difficult if nigh impossible. Devoid of inscriptions or collateral archaeological evidence there is little prospect to positively attribute the functions of anthropomorphic rock art in anything more than general terms. What we can state is that elaborate costumes and headgear, nudes, larger than life depictions, consorting with wild animals, and sacred symbolism seem to express special or elite identities and activities.

Ethnographic and textual sources suggest that a wide spectrum of exceptional or distinctive anthropomorphs were active in ancient Upper Tibet. These include divine manifestations, royalty, priests, spirit-mediums, ancestral personalities, mythic heroes, and bards. It is possible that all of these types of figures are represented in Upper Tibetan rock art, but which is which is a moot point. Although the attribution of a specific function or identity to a particular anthropomorph is not feasible, keeping in mind the dynamic nature of ancient society helps frame extraordinary rock art in a meaningful cultural context.

Determining the wider significance and purposes of rock art is predicated on an understanding of the archaeology, cultural history and ethnography of Tibet. This kind of Tibetological perspective along with a healthy dose of the imagination, will serve the reader well as they come face to face with the extraordinary anthropomorphs of ancient Upper Tibet. In this article I suggest the possible functions of individual compositions. But bear in mind: however one might perceive special anthropomorphic figures now, the exact reasons for their creation in ancient times lie buried with their makers.

In addition to the kinds of anthropomorphs presented here, there are other categories fit to be called ‘extraordinary’, which are not featured in this study. These include so-called ‘mascoids’ or anthropomorphs in emblematic form (see the Dec. 2011 Flight of the Khyung; Bruneau and Bellezza, 2013: “The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 28, pp. 5–161. Paris: CNRS:

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_28.pdf).

Another category of extraordinary anthropomorphs are those mounted on wild ungulates (see the July 2012 Flight of the Khyung). An extensive series of exceptional anthropomorphs is also found at the Thakhampa Ri rock art site in northwestern Tibet (see the Dec. 2013 and Jan. 2014 Flight of the Khyung). As for more ordinary human figures, such as hunters and herders, these shall be featured in upcoming issues of Flight of the Khyung.

I shall briefly comment on the dating of rock art furnished below. The chronological attributions provided are suggestive, not prescriptive. In the absence of reliable means for the direct scientific testing of rock art, gauging its age must be based on less formal and more indirect methods of study. This approach to dating is dependent on an analysis of subject matter, style, execution, physical condition, relative placement, and comparative study, among other parameters. I have spent two decades refining an understanding of Upper Tibetan rock art but there is still educated guesswork involved, as there is in the inferential dating of rock art the world over.

Picture Gallery, Comments and Analysis

I had the privilege of documenting for the first time many but not all of the extraordinary anthropomorphs depicted in this article. All photographs were taken by me.

Fig. 4. A squatting or stably poised figure, arms raised, with what appears to be a pair of prominent horns on its head. Late Bronze Age (post-1200 BCE) or Iron Age (600–100 BCE), western Tibet.

Legs wide apart with bits carved in between, this long, narrow figure may possibly include a phallic depiction. However, the physical aspect of the figure is also that of birth-giving. The pair of ‘horns’ on the head curve round until they almost meet to form a circle, as is encountered in wild yak rock art of the same period. There may be something in each hand of the lone anthropomorph but these are not identifiable. This composition may be that of a deity, mythic character or powerful priest / priestess.

In the Yungdrung (Swastika) or ‘Eternal’ Bon religion, there is a distinctive order of horned funerary gods that destroy demons associated with death (see Zhang Zhung, pp. 442–447). In Bon lore, there is also a class of priests (gshen and bon) and kings of the Zhang Zhung kingdom who don ‘horns of the bird’ (bya-ru), ‘horns of the horned eagle’ (khyung-ru) and ‘horns of extreme sharpness and intensity’ (dbal-ru). References to these horned helmets or feathered crests (Bonpo are no longer certain about the identity of these types of headdresses) are found in my publications, as well as in the work of scholars such as Dan Martin, Samten Karmay and Namkhai Norbu.

One of the oldest extant literary references to the bird horns of a deity is found in a circa 10th century CE Old Tibetan language ritual text of the Gathang Bumpa collection. She is one of a group of nine goddesses called zima (zi-ma / gze-ma), and her bird horns reach as high as the heavens (see pp. 181, 182 of my 2014: “Straddling the Millennial Divide: A case study of persistence and change in the Tibetan ritual tradition based on the Gnag rabs of Gathang Bumpa and Eternal Bon documents, circa 900–1100 CE” in Revue d’etudes tibétaines, vol. 29, pp. 155–243. Paris: CNRS.

http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/ret/pdf/ret_29_07.pdf).

As with the Zhang Zhung kings and ancient high priests, the bird horns of the zima goddess appear as a symbol of an exalted status, great power and tremendous ability.

Even older references to bird horns and horned eagle (khyung) horns are located in three funerary manuscripts of the Dunhuang collection (Pt 1134, 1136, 1194), writings that probably date to the 8th or 9th century CE. These kinds of headdresses were used by funerary priests (?) and by the psychopomp horses believed to carry the dead to the afterlife (for these Dunhuang references, see Zhang Zhung, pp. 509, 519, 522; Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet, pp. 230–232). According to Eternal Bon funerary literature, the bird horn equestrian headdresses functioned to cut a path through space to the otherworld. In Dunhuang and Eternal Bon texts, these funerary objects and activities occur in myths that were already considered to be of ancient origins. This brief introduction to the bird horn headdresses of olden Tibet must suffice for the time being. I will however return one day to this fascinating subject. Please stay tuned.

Ancient horned figures and horned helmets are known from various parts of the Eurasian continent. Many of these objects date to Late Bronze Age and Iron Age, and a goodly number are made of copper alloys. As we shall see, the majority of what seem to be horned anthropomorphs in Upper Tibetan rock art were created in the same timeframe as analogous figures in other Eurasian cultures. If this was an isolated case of parallels in form, function and age between far-flung peoples, no more comment would be necessary. However, this is not so. Upper Tibetan rock art, stylistically and thematically, is replete with broader cultural and regional influences. Mascoids, chariots, ‘animal style’ art, predator attack scenes, big game hunting compositions (depicting recurve bows, falconry and hounds), and the equestrian arts, etc. all point to seminal interactions with other parts of Inner Asia and beyond.

As my research shows, there are also many parallel features in the funerary archaeology of Upper Tibet and north Inner Asia. Although no direct links (clear vectors of dissemination and transfer) can be confidently postulated between the extraordinary anthropomorphs of Upper Tibetan rock art and objects from other areas of Eurasia enumerated below, they are in aggregate indicative of a deeply submerged cultural common ground as well as a Late Bronze Age and Iron Age zeitgeist that swept the continent.

For comparative purposes, let us review some of the most famous examples of horned anthropomorphs and horned headdresses in Eurasia. I will not provide website links to the objects listed because all are easily searchable online. A number of bronze horned helmets dating to the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age have been discovered in various parts of Europe. Among the oldest are two Bronze Age helmets recovered from a peat bog in Veksoe, Denmark. These helmets boast long, curved, tubular horns. A 2000 year-old bronze horned helmet was fished from the Thames. Known as the Waterloo Helmet, it is believed to have been used by pre-Roman Celts for ceremonial purposes. An Iron Age Thracian horned helmet of bronze, but of different construction to the specimen from England, was discovered in Bryastovets, Bulgaria.

An antlered anthropomorphic horned figure from Iron Age Europe graces the silver cauldron of Gundestrup, Denmark. This remarkable figure is surrounded by wild animals and is thought to depict the Celtic fertility god Cernunnos. Two Late Bronze Age figurines (in bronze) with horned headgear from Enkomi, Cyprus, are also identified as gods. They were found in a shrine where bull sacrifices were conducted. Moving eastwards, there are at least two 5000 year-old Proto-Elamite (southwestern Iran) copper statues of a striding figure wearing a horned headdress and boots with upturned toes. Not all horned figures depict males. Female horned figures of diverse types and materials have been found in Gaul, Tuscany, Sumeria and Luristan.

In India there is the long-forgotten goat-headed Jain god, Naigamesha. Even older is the so-called Marshall Shiva or Pashupati seal. The functions and identity of this steatite seal belonging to the Indus River civilization are hotly debated. What is undeniable is that the seated male figure dons a headdress surmounted by long, graceful corniculate objects. Another horned figure of Indic persuasion is the kirtimukha (tse-pu), a jewel bearing, snake devouring creature conferring protection and good fortune. The kirtimukha appears in Tibetan art of the Imperial period (650–850 CE ), but it may be known in that country from an even earlier date (the same can probably be said of elephants, peacocks and crocodiles). Although still not well understood, cultural interplay between India and Tibet extends back into prehistory as exemplified by cosmogonic and spirit mythologies.

Fig. 5. A copper alloy object with a horned kirtimukha or tsepu. This well cast specimen belongs to a class of objects that appears to be a kind of ornamental horse tack. Circa 500–900 CE. Private collection, Lhasa.

Finally, I will mention a unique horned figure discovered in the rock art of Mongolia. Regarding this petroglyph, see 2011: “Rock Art and Archaeology: Investigating Ritual Landscape in the Mongolian Altai” (eds. W. W. Fitzhugh and R. Kortum): http://www.mnh.si.edu/arctic/html/pdf/Rock%20Art%20and%20Archaeology%20Field%20Report%202011%20FINAL_webv4.pdf

Fig. 6. This red ochre figures stands in a manner not unlike the specimen in fig. 4. Other art from the same grotto in which this pictograph is found, suggests that this composition dates to the Early Historic period (650–1000 CE), central Changthang.

Again, it cannot be established beyond a shadow of a doubt that horns are intended in this depiction. Nevertheless, this attribution is strengthened by the above anthropomorph with hornlike extensions sharing the same aspect (fig. 4): legs spread apart, arms held up high. If horns are not indicated, then the protuberances on the anthropomorph’s head could possibly represent the ears of a wild animal or another kind of finial or embellishment. The wide chest and big arms impart a robust appearance, which is suggestive of a deity or heroic human. This composition was first published in Zhang Zhung, p. 213.

Fig. 7. An archer on foot pursuing a wild ungulate (most of which was effaced or not completed). Late Bronze Age or Iron Age, eastern Changthang.

This figure is part of a simple but forceful and handsome genre of pictographs, which is among the oldest known paintings in Tibet. The lines protruding from the head of the mustard-colored ochre anthropomorph resemble a set of horns. Alternatively, they could replicate some other kind of object, but given the size and shape of the motif, I think it is most plausible that ‘horns’ (cornual or feathered) are intended. Note how the animal has already been struck by the hunter’s arrow, a typical manner of depiction in Upper Tibetan venatic scenes. I discuss this exceptionally significant genre of ancient art in the books Divine Dyads, Zhang Zhung and in other publications, but a more detailed study is forthcoming.

Fig. 8. A red ochre mounted archer (much of the bow has been obscured) hunting a wild yak. It is located in the same small cave as fig. 7. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age, eastern Changthang.

This figure, which probably represents an actual hunter, as do others in the same cave, has three vertical lines extending from the top of its head. These shorter lines are most illustrative of feathers. Tibetan texts tell us that feathers adorned the heads of a variety of elemental deities, ancient Bon priests, and even some Buddhist figures such as the 14th century CE treasure revealer (gter-ston), Rigzin Godemtru (Rig-’dzin rgod-ldem-’phru).

Fig. 9. Another mounted hunter of wild yaks from the same location as figs. 7 and 8. Late Bronze Age or Iron Age, eastern Changthang.

This is another example of an ancient hunter with corniculate extensions on its head, legs dangling from its horse. Like the counterparts in figs. 7 and 8, this figure is coming in for the final kill. The shape of the weapon identifies it as a recurve bow, a powerful version of the bow that spread widely in Inner Asia, beginning in the second millennium BCE (for more details, see March 2013 Flight of the Khyung). The mane and ears of the horse are rendered as barbed lines and the saddle as a V-shaped form.

Fig. 10. A pair of anthropomorphic figures located in the same cave as figs. 7–9. Protohistoric period (100 BCE to 650 CE) or Early Historic period, eastern Changthang.

This pair of red ochre figures is situated in a hard-to-photograph recess in the rear of the cave. The pictograph belongs to a later phase of rock art at the site, which spans the Protohistoric and Early Historic periods. The shadowy figure on the left seems to have a pair of horns, which in form are comparable to those on the Waterloo Helmet discovered in the Thames. Although seemingly less likely, it cannot be excluded that these pinnacles are braids rather than horns. A definitive judgment about the nature of the depiction is simply not feasible, given the limited amount of pictorial evidence available. Both anthropomorphs wear long robes gathered at the waist, a style of ancient and contemporary clothing in Tibet. The robe of the left figure opens down the middle, somewhat resembling the gyaluche (rgya-lu-chas), a type of clothing traced back to the Imperial period (650–850 CE). The figure on the right may have long flowing hair but the composition is too obscured to know for certain.

Fig. 11. A turbaned figure with two hornlike extensions. Probably Vestigial period (1000–1250 CE), eastern Changthang.

This figure is found amidst a group of red ochre compositions and inscriptions that may possibly have been created by Tungusic peoples. The Tungusic tribes originally came from eastern Siberia and Manchuria, and certain offshoots ruled over northern China for more than a century. However, proximate inscriptions could not be deciphered by experts in the ideograms of the Liao (907–1125 CE) and Jin (1115–1234 CE) dynasties that I approached for help. Thus the historical origins of this figure and other pictographs in the same group remain enigmatic. The anthropomorph has eight spots at the waist possibly simulating a belt studded with silver, stones or shells. Such types of belts are still worn by women belonging to the nomadic tribes of Tibet. The identity of the two lines extending above the full, round turban is unclear. Nevertheless, the pose of the figure, arms raised and legs partly spread, recalls that of more ancient rock art figures exhibiting horns, feathers or antennae. Perhaps the artist was mindful of longstanding cultural continuities operating in Upper Tibet but this is very difficult to verify. A future issue of Flight of the Khyung will be devoted to the anomalous group of pictographs and accompanying inscriptions touched upon here.

Fig. 12. One of many different subjects painted inside a pyramidal niche. Early Historic period or Vestigial period, eastern Changthang.

The hornlike headgear of this orange-red ochre anthropomorph resembles headdresses traditionally worn by women in Central Tibet and in Guge and Purang in western Tibet. The long, full robe of the figure also hints at female clothing. Yet, there are insufficient details in this depiction to pronounce the identity of individual anatomical and costumery details with any surety.

This figure is one of more than a dozen found on a single vertical slab of rock. I discuss this important group of pictographs in Zhang Zhung, p. 175, and in other publications. In 2010, on the Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition I, much more detailed images of this rock art were obtained, permitting closer scrutiny of individual figures. Among the subjects on this stone are three vertically arrayed specimens, which in descending order include a horned eagle, wings outstretched,* the avian figure pictured above and the more human-like figure in fig. 14. I have hypothesized that this trio of figures depicts the magical transformation of the khyung, first to an intermediate bird-man figure and then down to one fully human, as part of an origins myth connected to the Khyung clan (several Early Historic period Khyung / Khyung-po inscriptions are found in the area; for one of these, see Jan 2013 Flight of the Khyung). The figure shown in fig. 13 has a beak, long bird-like neck, diamond-shaped wings or arms, and a triangular lower body. The tricuspidate crown may represent the bird horns crown (bya-ru) of the Tibetan literary tradition. This is among the most archaeologically compelling evidence to date for such an object having existed in pre-Buddhist Upper Tibet.

For this khyung, see Jan. 2012 Flight of the Khyung, fig.1.

Fig. 14. This anthropomorph forms the lowest figure in the triad described above. Protohistoric period, northwestern Tibet.

This figure has more human anatomical traits (head, torso, arms, legs) than its two counterparts on the same slab of rock. Yet, like fig. 13, this anthropomorph has three forked lines extending above the head. This, too, may be an example of the bird horn crown. The geographic location of this rock art, the association of the crown with birds, the inclusion of a horned eagle in the composition, as well as the addition of other totemic / warrior god animals (yak and tiger), the swastika, sun and moon, etc., reproduce fundamental religious and mythic themes embraced by Eternal Bon literature and associated with the Zhang Zhung kingdom.

Fig. 15. A composite bird-human figure rendered in a black pigment. Possibly Early Historic period, eastern Changthang.

Tibetan literature and folk culture speaks of wizards and local deities assuming the guise of vultures, hawks and eagles. In contemporary Upper Tibet, spirit-mediums whilst in trance are thought to be transformed into raptors in order to carry out curative rituals. Ancient bon priests are supposed to have taken on the form of birds of prey to eliminate harmful demons and as an expression of their enlightened status. Mountain gods are also said to emanate as horned eagles and other birds. For more on ornitho-anthropomorphic figures, see my “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet” in Rock Art Research, vol. 17 (1), pp. 35–55. Melbourne, 2000. Some indigenous deities and early priests bore various ornithic traits. These range from robes of white vulture feathers to eagle claw weapons, bird heads, and of course bird horn crowns.

Fig. 16. Another composite bird-human figure. This one is painted in red ochre with a minimum of fine, straight lines. Protohistoric period or Early Historic period, Eastern Changthang.

This vibrant and evocative figure is in close proximity to a couple of raptor pictographs of the same time period. They seem to form an interrelated panel of rock paintings on which much was added subsequently. This figure may possibly have a crest or horns. It appears to be portrayed in midair, as are the raptors that surround it. The bi-triangular form is occasionally encountered in wild yak rock art as well. For this composition also see Bruneau and Bellezza 2013, p. 18.

Fig. 17. A figure with both anthropomorphic and avian qualities painted in a black pigment. Historic era (period uncertain), eastern Changthang.

A head ornamented with feather-like lines and possessing wing-like arms, this figure may portray a shaman, priest or deity. It grasps a large crescent-shaped object with the right hand. The round head is punctuated by relatively large eyes and an open mouth. The mixing and merging of human and bird traits in the rock art of Upper Tibet is one of considerable historical persistence, reflecting long-term preoccupation with the sky and celestial phenomena among a people who inhabited the highest land on earth. An exaltation of height and the attraction of the heavens is also seen in the siting of ancient funerary and residential sites at 5200 m to 5600 m above seal level.

Fig. 18. In this composition a bird-like figure (left) and an anthropomorph (right) are acting in concert. Protohistoric period, western Changthang.

The outstretched arms of both figures mimic one another, suggesting a dance or a ritualized or mystical behavior. The head of the figure on the left appears to be covered in feathers. Its triangular body and arms are also bird-like in form. The body of this subject is contained inside a circle, creating an outer body or some other kind of encompassing form. The figure on the right was executed to be quite ordinary in appearance. The style of this rock art and the shallow carving technique used are comparable to Thakhampa Ri, which also features ornitho-anthropomorphic rock art.

A probable raptor with raised wings and an anthropomorph with objects in both hands move in sync, as if dancing. Upper Tibetan rock art contains many raptors with large triangular bodies and spread wings like this one. Any number of Tibetan cultural themes could be represented in this curious composition. Shamanizing with a patron avian spirit, a theophany of the clan deity in the form of a bird, various bardic themes, or the carrying out of a ritual are some of the potential activities encapsulated here.

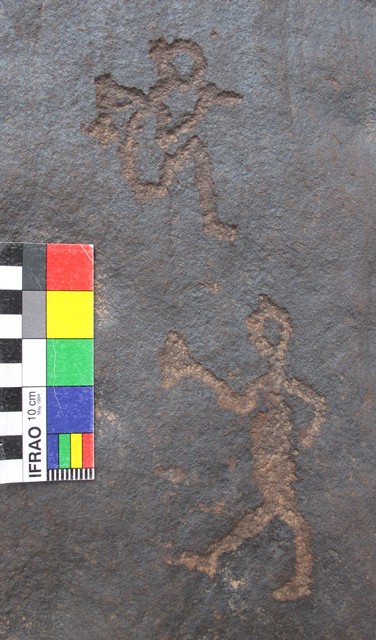

Fig. 20. Two anthropomorphic figures that seem to be dancing or carrying out another kind of choreographed activity. Late Bronze Age or or Iron Age, western Tibet.

Instead of an avian partner, two anthropomorphs are joined in a whirl of movement. Their arms are extended in differing ways and the figure on the right is raising a leg. The figure on the left appears to be depicted with male genitalia. The other anthropomorph, then, might be a female, but any number of alternative identities for these twin figures, mundane or supermundane, can be envisioned. Both figures seem to be wearing hats or headdresses. In the harsh climate of Upper Tibet, head coverings were and are an essential part of any garb, the many religious and social uses for them notwithstanding.

The flexed arms and legs of this figure are reminiscent of a dancer or acrobat. The tiny head is rendered perpendicular to the body. There are three small protrusions on the head set in ambiguous positions. A survey of Upper Tibetan rock art suggests that one of these could possibly depict the muzzle or mask of an animal and the other two horns, feathers or simply ears, but confirmation remains elusive, as does a determination of the functions and identity of this composition. Possibilities range from an ordinary person in celebration to a mythic or divine personality in an ecstatic state.

This evocative scene portrays what appears to be flute player sitting above an anthropomorph in an attitude of dance or ritualized behavior. The figure with something at its mouth was first published in the December 2012 Flight of the Khyung, where it is referred to as the oldest known depiction of music making in Tibet. Given the inherent pictorial ambiguities of the composition, however, the object near the figure’s mouth could be something other than a flute, but I think not. This anthropomorph seems to have its hair pulled back in a bun. The identity of the wing-like motif on its back is unclear. The lower carving, despite exhibiting a somewhat different colored patina, appears to form an integral composition with the ‘flute player’. This is indicated by the employment of the same carving technique, producing precisely the same type of markings on the stone surface. The inferior anthropomorph holds something in one of its hands. One arm akimbo and one leg raised, graceful and stately movement is conveyed by this figure. A ritual or mythic theme comes to mind for this composition, but any such inference is of course speculative.

Next month: Coming face to face with the holy ancients: More extraordinary anthropomorphs!