December 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung: destination ancient Tibet! This month’s issue of the great bird features the first part of an article about the birth of civilization in uppermost Tibet, the highest land in the world. The momentous rise of a new cultural and technological world at the end of the Bronze Age, nearly 3000 years ago, is seen through a peculiar type of monument. This necropolis, one of the best preserved in the Tibetan upland, is a strange sight with its ghostly fields of standing stones and mortuary temples. This is the first work ever published that deals exclusively with the final phase of the Bronze Age in Upper Tibet, supplying readers with an entirely new perspective on the dawn of civilization in Tibet.

The writing of this article was made possible by a grant from the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York). This year’s exploration of Tibet was underwritten by the Tise Foundation (Chicago) and Joseph Optiker (Burglen). I heartily thank these institutions and individuals for their professional support.

Talus-blanketed Red House Necropolis of Upper Tibet: Cross-cultural exchanges with the north at the end of the Bronze Age – Part 1: Indigenous characteristics

The first part of this article is divided into the following sections:

- Introduction to Talus-blanketed Red House and other stelar necropolises

- Description of Talus-blanketed Red House

- Dating Talus-blanketed Red House

- Geographical, ideological and sociopolitical characteristics of Talus-blanketed Red House

Chronological terminology employed in this article is as follows:

I. Prehistoric Epoch

Late Bronze Age: ca. 1500–1000 BCE

Final Bronze Age: ca. 1000–750 BCE

Iron Age: ca. 750–100 BCE

Protohistoric period: ca. 100 BCE to 600 CE

II. Historic Epoch

Early Historic period: ca. 600–1000 CE

Introduction to Talus-blanketed Red House and other stelar necropolises

This article highlights an important prehistoric funerary site in Upper Tibet known as Talus-blanketed Red House (Khang-dmar rdza-shag). With its relatively intact arrays of standing stones and temple-tombs, this necropolis provides us with the clearest view yet of the cultural complexion of Upper Tibet at the end of the Bronze Age (circa 970–820 BCE). Talus-blanketed Red House is the oldest funerary site to be directly dated in the western uplands, situating certain foundations of Tibetan civilization in the highest part of the Tibetan Plateau.

This work describes funerary structures found at Talus-blanketed Red House and evaluates their age based on a calibrated date obtained from human bones collected at the site. The article also furnishes an assessment of the possible ritual functions and economic and sociopolitical forces behind the establishment of Talus-blanketed Red House (TBRH), as well as an analysis of the site’s role in Inner Asian cross-cultural processes at the close of the Bronze Age.*

For the purposes of this study, North Inner Asia denotes southern Siberia, the Altai, Mongolia, western Gansu, western Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and eastern Kazakhstan, and may be extended to adjacent regions. The Tibetan Plateau, including the Tibet Autonomous Region, Dokham, Ladakh, Baltistan, Spiti, Dolpo, Mustang, etc., constitute what I call South Inner Asia. The use of the geographical label “Inner Asia” for both territories is intended to highlight the interrelated environmental, economic, and cultural elements of their archaeological assets.

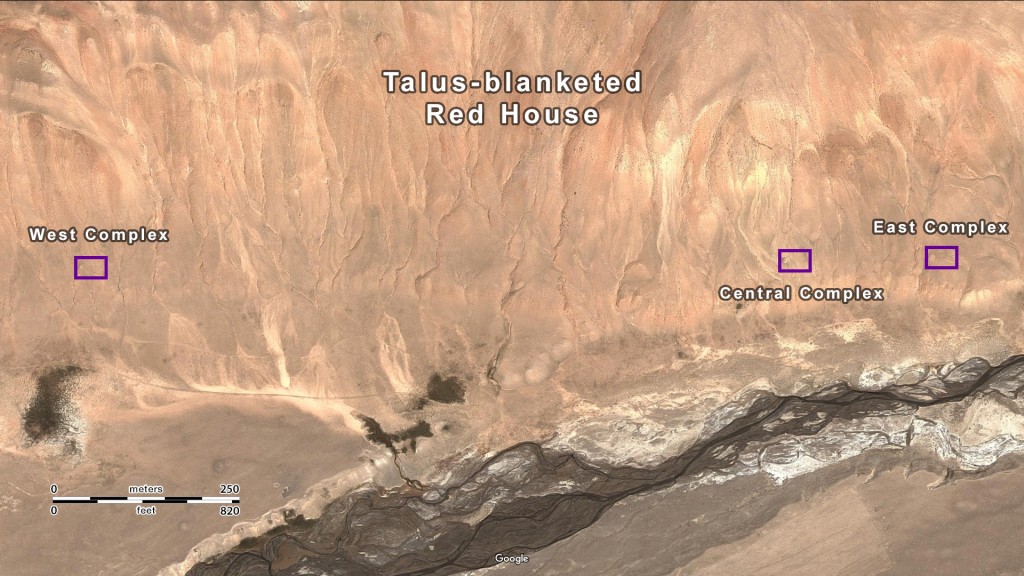

Fig. 1. Tibet and adjoining territories with the location of Talus-blanketed Red House. Map amended by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza.

Fig. 2. A portion of the western Changthang with Talus-blanketed Red House. Map amended by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza.

Fig. 3. Talus-blanketed Red House and environs. Map amended by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza.

Talus-blanketed Red House (TBRH) is located on the western portion of the Changthang (Byang-thang), the vast tablelands of northwestern Tibet with an average elevation of around 4700 m. In modern administrative terms, this archaeological site is situated in the Lowo (Lo-bo) subdivision of Tong Tsho (Stong-mtsho) Township, Gertse (Sger-rtse) County, Ngari (Mnga’-ris) Prefecture, of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). Traditionally, TBRH was part of Changma (Byang-ma), a pastoral region making up one of the Nine Confederacies of Drongpa (’Brong-pa tsho-dgu). The site is within a few kilometers of the Nagchu (Nag-chu) Prefecture border. The adjacent region of Nagchu was traditionally known as the Six Confederacies of Naktshang (Nag-tshang tsho-drug).

TBRH (4675–4685 m el.) is a necropolis or multifaceted mortuary site consisting of arrays of stelae, temple-tombs and funerary enclosures scattered over a transection of 1.2 km. The necropolis is sited on a gently sloping sandy and turfy bench that rises 7–25 m above the flood plain of Valley Head (Rong-mgo) valley. The sizable river that flows past the TBRH originates 25 km to the south on the eastern flanks of She Kangjam (Shel-gangs lcam), one of the highest and most heavily glaciated mountains on the Changthang. According to an administrative map of the TAR, the river that runs below TBRH is the Sha Tsangpo (Sha gtsang-po). It flows east-northeast past the site and then bends to the northwest before debouching into the Tong Tsho (Stong-mtsho) basin, 45 km away. She Kangjam (el. 6822 m) is clearly visible from TBRH. It is considered to be the abode of a goddess named Mentsun Kangjam Lhamo (Sman-btsun gangs-lcam/gangs-’jam lha-mo), an important territorial spirit (yul-lha) of the region.*

On the sacred geography and lore of this sacred mountain see Bellezza 2005, pp. 80, 298.

I first carried out a reconnaissance mission to TBRH in June 2002, publishing three accounts of it among descriptions of other archaeological sites (Bellezza 2008: 90–92; 2014b: 130–135; 2014c: 115, 148, 150). In October 2016, I returned to TBRH to conduct another survey of the surface remains with the help of my partner and two associates. This recent survey served to verify and augment data collected in 2002. Measurements of the various structures and an appraisal of their morphological characteristics were carried out. In total, 500 photographs of the site were taken. Due to time limitations, it was not possible to produce field maps, nor did my work agenda permit an assessment of sub-surface aspects of the necropolis.

The biggest change observed at TBRH between 2002 and 2016 was the excavation of one of the temple-tombs by grave robbers. The looting and destruction of funerary sites throughout Upper Tibet has become a huge problem in recent years. Thus far, little effort has been made by the TAR administration to stem this disturbing trend. In the interests of conservation, the GPS coordinates of the various structures of TBRH will not be given in this article online.

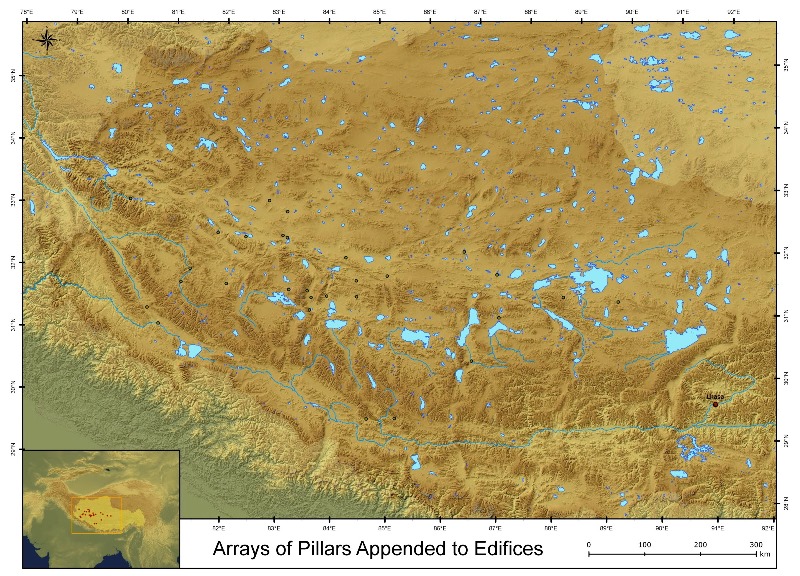

Fig. 4. Locations of the thirty-one sites of necropolises in Upper Tibet consisting of arrays of stelae or pillars appended to temple-tombs (after Bellezza 2008, p. 738; 2014b, p. 630).

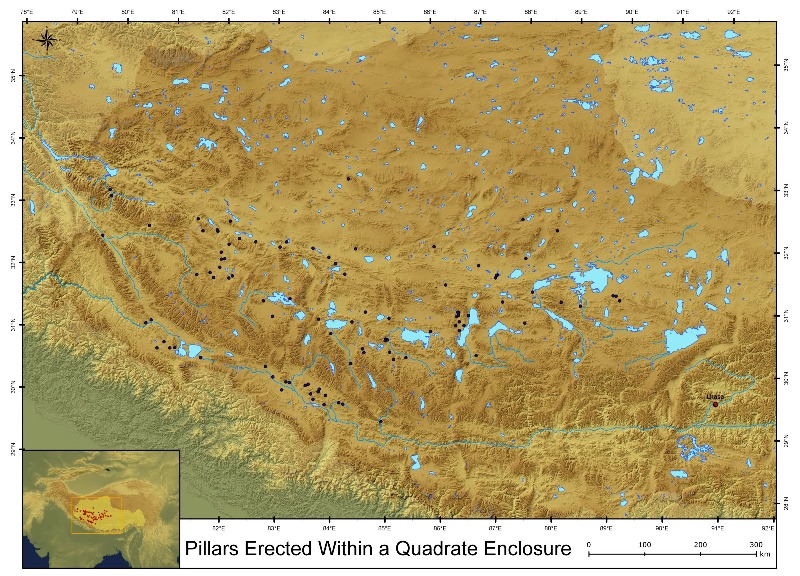

TBRH is still hardly known to the academic community despite its great importance to the prehistory of Upper Tibet. It is one of thirty-one sites in Upper Tibet dominated by arrays of pillars or stelae appended to temple-tombs (hereafter called stelar necropolises) documented to date.* These monuments feature multiple rows of stelae in a rectangular formation set on the east side of a masonry edifice. The edifices have a quadrate plan and contain one to five funerary chambers. The thirty-one sites of this typology are distributed between eastern Namru (Gnam-ru) in the east and Gar (Sgar) and Ruthok (Ru-thog) in far western Tibet (89° 26′ to 80° 11′ E. long.). This large territory extends across the central and western Changthang and much of the Tö (Stod) region farther west. It is the same area in which archaic all-stone corbelled residences and several kinds of funerary enclosures are also concentrated, delineating a contiguous pre-Buddhist (pre-7th century CE) material cultural zone.

Twenty-nine of these sites are tabulated in Bellezza 2008, pp. 673, 674; 2014b, pp. 581, 582. The other two sites of this typology are reviewed in the November 2010 Flight of the Khyung (more detailed treatment of them is pending). For a description and cross-cultural analysis of this type of Upper Tibetan funerary monument, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 83–108; 2014, pp. 13–16; February 2011 Flight of the Khyung. The thirty-one sites of stelar necropolises were documented by the author on a series of expeditions between 1995 and 2010. Except for the brief mention of this type of monument by the Chinese archaeologist Huo Wei (2005) and the Tibetologist Dondrup Lhagyal (2003), I am aware of no other academic references to them. This underlines the nascent state of archaeological investigation in much of the TAR.

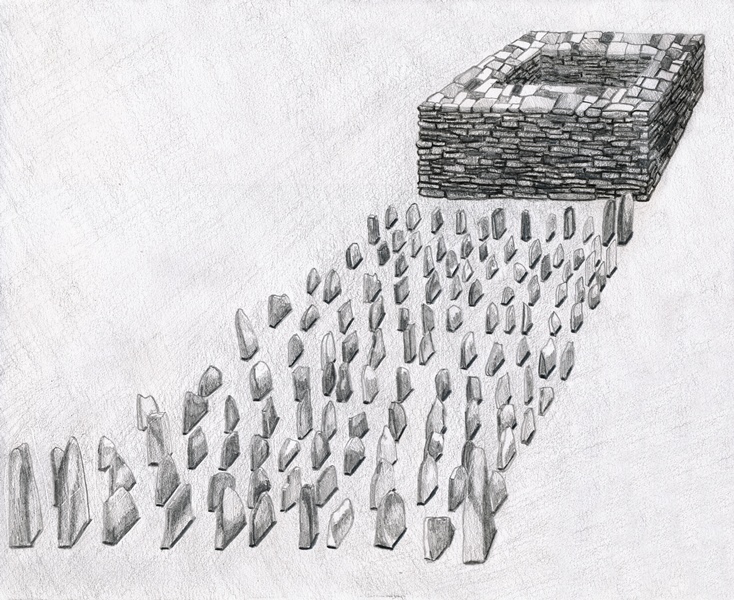

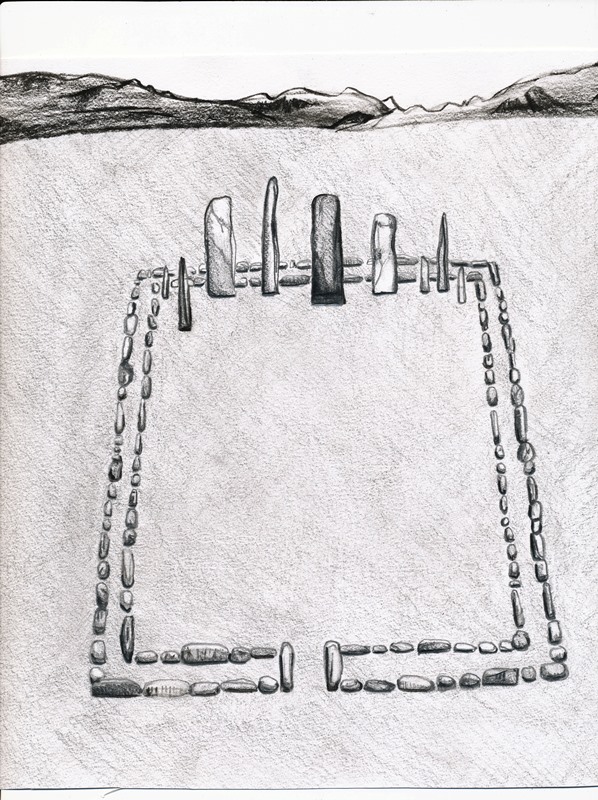

Fig. 5. An artist’s partial reconstruction of a small stelar necropolis (after Bellezza 2014a, p. 13).

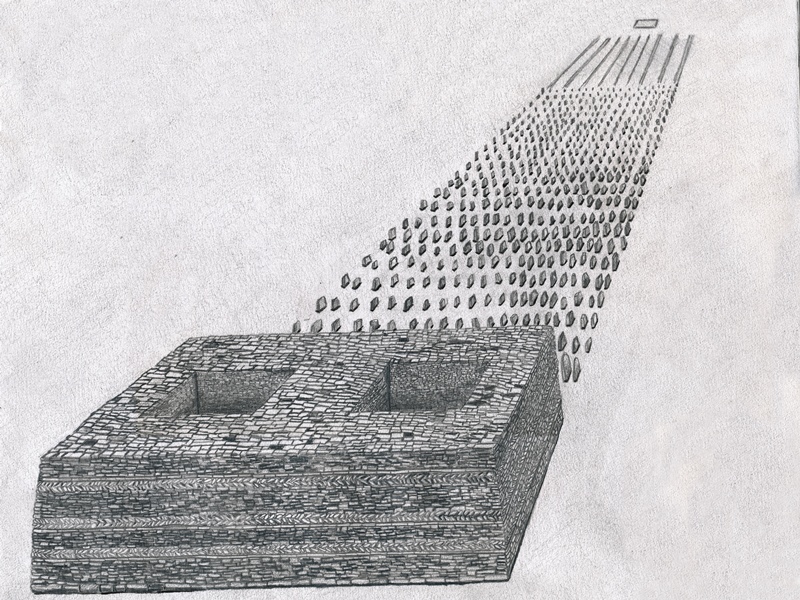

Fig. 6. An artist’s partial reconstruction of a large stelar necropolis with a small enclosure in the foreground (after Bellezza 2014a, p. 13).

Most of the thirty-one stelar necropolises have a single array of stelae with a companion temple-tomb.* However, there are also several sites with two complexes, one with three complexes (TBRH) and one with six complexes standing close to one another. The stelar necropolises are usually situated on the edge of plains and broad slopes. Invariably, they are located on level or almost level, well-drained terrain, removed from open sources of water. Most of the concourses of stelae and appended edifices are generally oriented in the cardinal directions. These structures are laid out along an east-west axis that varies less than 20° from the cardinal points. However, a few complexes are more closely aligned in the intermediate directions. All thirty-one sites of stelar necropolises have wide open eastern vistas. Views in other directions tend to be more constrained, particularly in the west.

In Tibetan, this kind of stele is called ‘long-stone’ (rdo-ring) or ‘register’ (tho). In the folklore of Upper Tibet, they are often attributed to the Mon, a tribe of nebulous ancient origins, not to be confused with existing Mon tribes of the Himalayan periphery.

Depending on the size of each complex, there were between 100 and 3000 stelae planted in the ground in evenly distributed rows. The stelae protrude 15 cm to 1.4 m above the ground surface, with an additional 30–40% of length underground for support. Smaller specimens tend to be naturally occurring pieces of rock (sandstone, porphyry, etc.) with pointed tops, while some larger ones were cut into tabular shapes. The east-west rows of stelae are spaced 40 cm to 1.2 m apart and each stone in a row is situated 30 cm to 1 m from one another. The two broader sides of the stelae face in the north and south directions, as do the longs sides of the arrays themselves. Lines of stone slabs embedded in the ground edgewise in single or double courses are commonly encountered inside the concourses, bounding their edges or extending in a grid formation east of the stelae. These slab walls are between 3 m and 30 m in length.

Immediately west of the concourse of stelae is the temple-tomb, a heavily built masonry edifice. It is not uncommon however for rows of stelae closest to the temple-tomb to have been uprooted. The temple-tombs have four uniform walls uninterrupted by overlapping extensions, fixtures or apertures. These are adroitly constructed structures with a coursed-rubble texture. Some exterior walls are interspersed with several courses of thin bond-stones and/or herring-bone courses for added structural integrity. The temple-tombs vary in length from 3 m to 65 m and were probably up to 6 m or more in height. The tallest extant walls are 3.5 m to 4.2 m but an indeterminate portion of their uppermost sections are missing. Edifices with taller walls slightly taper inward, in what is referred to as the ‘Tibetan fortress’ style. None of the roofs of the temple-tombs are intact but these were almost certainly constructed with corbels, bridging stones and sheathing to produce an entirely stone flat roof. Early residential edifices in Upper Tibet were built with all-stone roofs in the same fashion.

Depending on their size, the temple-tombs have one to five inner chambers. These appear to have had a mortuary function. However, no human remains have been detected inside (the chambers have been scoured clean of artifacts and other materials). The mortuary chambers are encased in massive walls 60 cm to 2 m thick, and some of the larger edifices also have inner walls composed of a finer masonry fabric. No apertures in the sides of these chambers have been detected, suggesting that they were accessed from above. The bottom of the chambers is situated above the surface of the surrounding terrain. It has not been determined what type of interment or other deposits they might have contained. The prominent aboveground aspect of the edifices, their relatively large size, and the radiation of stelae, slab walls and enclosures from them strongly suggest that the temple-tomb was the nucleus of the necropolis. As the tallest structure at the stelar necropolises, the temple-tomb dominates the local landscape, and probably served as the nexus of ritual dispensation, ceremonial observance and social assembly. It is for these reasons that I refer to these edifices as temple-tombs.

A variety of other types of funerary structures are found at the stelar necropolises. The most common types are quadrate and sub-rectangular enclosures with single-course and double-course perimeter walls. These perimeter walls contain blocks and slabs of stone flush with the ground surface or protruding as much as 40 cm above it. The enclosures are mostly between 2.5 and 14 m in length. Smaller rectangular structures composed of upright slabs laid neatly in the ground are found at some necropolises, immediately east of the array of standing stones. Small pieces of quartz and red sandstone scattered around some sites appear to have been minor structural or decorative features.

Description of Talus-blanketed Red House

Overview

The TBRH necropolis sits on a narrow esplanade on the north side of the broad Ronggo valley, which is bounded on both sides by low-lying ridges. The ridgeline immediately north of the necropolis rises approximately 70 m above the site.* To the west the vista is constrained by a curving ridge barricading that side of the Ronggo valley. The view to the south is mostly open and, as already noted, the sacred mountain She Kangjam is visible in that direction. Toward the east, the vista extends for many kilometers. The three similarly sized and designed complexes of TBRH form a single line of structures along the east-west running esplanade. The three complexes are directly in line of one another, paralleling the orientation in the cardinal directions of the individual temple-tombs and arrays of pillars of the site. Although they are set more than 1 km apart, the West Complex and East Complex deviate from a due east bearing by only a few thousandths of a minute, emphasizing the great importance placed on the alignment of TBRH by its builders. The single line spatial configuration of TBRH is unusual. The other five sites of stelar necropolises with more than one complex of pillars and temple-tombs are more tightly aggregated abreast one another. Due to the limited width of the esplanade, it was not possible to place the three complexes of TBRH side by side. The river that runs through the Ronggo valley is situated about 500 m from the West Complex of TBRH, while it hugs the base of the esplanade at the Central and East Complexes. The esplanade rises higher above the valley floor towards the east or downstream.

There is a small prayer flag mast on the ridgetop directly above the west complex of TBRH. It was recently erected at the behest of a lama from Kham (Khams) after local residents complained that inauspicious influences were emanating from the site. The raising of the prayer flag mast was part of a pacification ritual. Shepherds consider the site kanyenpo (bka’-gnyan-po), reflecting the belief that it can harm those who disrupt it in any manner. Pre-Buddhist monuments in Upper Tibet are commonly perceived by herders (’brog-pa) as harboring spirits that are potentially dangerous. On this subject see Bellezza 2008, pp. 22, 23. There are no Buddhist monuments or emblems at TBRH; the site was not redeveloped for later religious or economic practices. A lack of redevelopment was commonplace in Upper Tibet, with many early archaeological sites being neglected until the modern period. Environmental decline and alternative settlement patterns inspired by Buddhist sensibilities played roles in this abandonment. Now many pre-Buddhist monuments that previously escaped destruction are being decimated by looters, housebuilding, road construction and other modern development projects. On threats to the archaeological heritage of Upper Tibet, see the April 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 7. View from the south of Talus-blanketed Red House with the West Complex in the center of the photograph. The West Complex sits on elevated ground paralleling the Ronggo valley. Note the prayer flag mast just visible on top of the ridge directly above the West Complex.

Fig. 8. View to the south from the West Complex. The Ronggo valley and river flowing through it occupy the foreground and midground of the photo. In the background is the sacred mountain She Kangjam.

The temple-tombs of TBRH were made from brown and gray quarzitic sandstone which is abundant in the locality. Some of the exterior faces of stones employed in construction were roughly cut into shape, while others were used unshaped. Around half of the stones can be categorized as slabs (having a thickness to length ratio of more than 1:4). The remaining building stones can be categorized as blocks (thickness roughly equal to length and width). Stones used to build the temple-tombs are of variable length (15 cm to 55 cm). Indications from the three complexes at TBRH, as well as other sites of the same typology, show that the temple-tombs had a coursed-rubble fabric, but one that may have been rather irregular in places because of the variable thickness of the stones. Due to the extreme degradation of these structures, it is not clear whether mortar was used in the seams. Some all-stone corbelled residences in Upper Tibet have drystone masonry. Most of the stone members used to build the outlying funerary enclosures are naturally occurring pieces of rock.

West Complex

The terrain around the West Complex declines gently to the south and is dissected by several gullies and rivulets. The same topographic conditions prevail at the Central and East complexes; they appear to be the result of more recent geomorphological modifications to the landscape. The terrain was probably more even when the necropolis was founded. Nevertheless, the siting of the three complexes has proven sound: they are not in imminent danger from flooding, erosion or other natural forces.

Fig. 9. View of the West Complex from the southwest. Both the temple-tomb and array of stelae are visible.

Fig. 10. The array of stelae and appended temple-tomb of the West Complex from the west. The view to the east is the most profound at the site.

Fig. 11. All but the most easterly stele in the array of stelae appended to the temple-tomb, West Complex.

The West Complex of TBRH is isolated from the other two complexes. The Central Complex is situated nearly 1 km to the east of the West Complex, while the Central and East Complexes are in eyeshot of one another and spaced 165 m apart.

Like the array of stelae immediately to the east, the temple-tomb of the West Complex is neatly oriented in the cardinal directions. The temple-tomb of the West Complex measures 3.15 m (east-west) by 5.5 m (north-south). It has been reduced to 1.1 m to 1.5 m in height, but it was once substantially taller. The top of this structure is now highly eroded and no signs of the central chamber are visible. The south wall of the temple-tomb is intact to a height of 50 cm and is composed of five vertical courses of partially hewn sandstone slabs. The west wall has two exposed vertical courses of masonry, the north wall one or two, and the east wall only one vertical course of intact stonework. These extant wall fragments have subsided and buckled over the centuries. What appears to be a plinth underpinning the edifice or a retaining wall shoring it up is visible on the south side.

Fig. 12. The south side of the temple-tomb, West Complex. Note the coherent wall segment composed of both blocks and slabs of stone. Below the edifice are two vertical courses of masonry that appear to be vestiges of a plinth or retaining wall.

Fig. 13. The heavily degraded north side of the temple-tomb, West Complex.

The length (east-west) of the concourse of stelae is uncertain. The concourse of stele as it now stands is 30 m in length, however, originally it is likely to have been at least 36 m long. The most distant stele is located 55 m east of the east edge of the temple-tomb. This stele is situated 8.5 m east of the next standing stone in what persists of the array. Moreover, the most westerly stele in situ is planted 6.2 m from the east side of the temple-tomb. Indications from other sites suggest that stelae once reached much closer to the temple-tomb. The array of standing stones is now 14 m wide (north-south), which appears to approximate its original extent. There are 188 stelae still standing in the array of the West Complex and around fifty prostrate specimens among them, 50 cm to 1 m in length. Extrapolating from the spatial distribution of the stelae in situ, it appears that there were originally around 720 of them in fifteen or more east-west rows. Many of the intact stelae are 50 cm to 1 m in height. The smallest stelae extend 15 cm above the surface, excluding many broken specimens (some of which are even shorter). The tallest intact stele (1 m x 40 cm x max. 15 cm thick) stands near the southeast corner of the array. Many of the standing stones in all three complexes host orange climax lichen and are extremely eroded.

Fig. 14. The entire array of stelae of the West Complex viewed from the east. Note the isolated tabular stele in the foreground.

Fig. 15. Array of stelae from the northwest, West Complex.

Fig. 16. Array of stelae viewed from atop the appended temple-tomb, West Complex. The highly fragmentary nature of this array is clearly visible.

Fig. 17. Close-up of stelae nearest the temple-tomb, West Complex. Patches of orange climax lichen can be seen on some of the standing stones.

The most easterly stele in the West Complex is tabular (65 cm high x 45 cm wide x max. 8.5 cm thick) and has cleaved in half. This outlier appears to mark the eastern edge of the West Complex. Approximately 7 m farther east is a gully dissecting the esplanade. The most easterly stele stands inside an enclosure aligned in the cardinal directions. The perimeter of this enclosure is comprised of double-course slab walls embedded in the ground edgewise. Three of the perimeter walls are partially intact and the enclosure measures at minimum 1 m (east-west) by 2.1 m (north-south). These walls are composed of small slabs (15 cm to 40 cm long) laid in parallel and spaced around 20 apart. In between the outlier stele and the rest of the dispersion of standing stones is a single-course, north-south running slab wall embedded in the ground (9.1 m in length). Individual slabs in this wall are between 30 cm and 70 cm in length and protrude as much as 20 cm above the surface. Near the most easterly stele is a dislodged specimen 1.2 m in length. There are three other uprooted stelae (70 cm, 1.3 m, 1.3 m long) in the gap between the outlier stele and the rest of the array of standing stones.

Fig. 18. The most easterly stele in the concourse of the West Complex. Note how this standing stone has been cleaved in half. As with other tabular stelae, the two broad sides of this specimen face north and south. A double-course slab wall embedded in the ground can be seen to the left of the stele.

Fig. 19. The northwest corner of the small slab wall enclosure in which the most easterly stele stands, West Complex.

Fig. 20. A single-course slab wall situated between the main dispersion of standing stones and the most easterly stele, West Complex.

A highly fragmentary enclosure (FS1) is located 3.3 m west of the west side of the temple-tomb. This structure (3.8 m x 2.8 m) has been deformed by geomorphological changes and now sits at the edge of an eroding gully. The perimeter walls consist of a single course of stones, each up to 70 cm in length. A single standing stone (40 cm high) is located 13.5 m northwest of the temple-tomb. Nearby are several dislodged stones up to 55 cm long. These stones appear to have been part of another outlying funerary structure (FS2).

Fig. 21. Quadrate funerary enclosure FS1, situated just west of the temple-tomb, West Complex. This funerary structure occupies the left half of the middle band of the photograph.

Fig. 22. Vestiges of a funerary structure FS2, West Complex.

Intervening funerary structures

Twelve funerary structures were detected between the West Complex and Central Complex of TBRH. Most structures are quadrate (square and rectangular) enclosures and are mainly comprised of perimeter walls. However, a few structures are too degraded to ascertain their shape. There may well be other funerary structures at TBRH that are so degraded as to escape detection.

The first of these funerary enclosures (FS3) is situated 26 m north of the northeast corner of the array of stelae. This structure is partially intact (approximately 30% of the double-course and multicourse perimeter walls are still in situ). The perimeter walls of this quadrate structure are aligned in the cardinal directions and measure approximately 4.7 m (east-west) by 3.8 m (north-south). The stones used to construct this enclosure are as much as 70 cm in length and protrude a maximum of 30 cm above the surface of the ground.

Fig. 23. Quadrate funerary enclosure FS3. Note the slabs of stone embedded in the ground edgewise that make up what remains of the structure. Also note the West Complex in the background. Beyond it the author’s camp can be seen in the valley bottom.

A more elaborate funerary enclosure (FS4) rests on a gentle slope at the foot of the enclosing ridge, 88 m northeast of the array of stelae.* This highly dissolute structure is situated on the far side of a gully from the West Complex. The walls consist of double and triple courses of larger slabs embedded into the ground edgewise. The perimeter walls are not aligned in the cardinal directions. The slabs used in construction are 40 cm to 90 cm in length and protrude as much as 40 cm above the surface. The parallel slab courses are 70 cm to 80 cm in thickness. The structure is composed of two interlocking square enclosures with overall dimensions of 10.4 m by 9.9 m. Sparser remnants extend north beyond the northeast side of the structure for 5.5 m.

In Bellezza 2014b, p. 133, this structure is designated FS1.

Fig. 24. A view of the more complex funerary enclosure FS4. In the background members of the survey team at the West Complex are visible.

Fig. 25. Another view of funerary enclosure FS4 with She Kangjam soaring in the background.

Fig. 26. Slab wall traces in funerary enclosure FS4. Note how the slabs project prominently above the ground surface.

A smaller funerary structure (FS5) is situated on the east side of a gully 50 m southeast of FS4.* This densely knit funerary structure was cleaved open by the action of running water, exposing three or four vertical courses of masonry with an overall height of 70 cm. What is visible of this random-rubble texture structure measures 2.5 m in length. This structure has endured despite at least fourteen years of exposure to the elements.

This funerary structure is designated FS2 in Bellezza 2014b, pp. 133, 134. For a photograph of this structure and the human bones it contained, see Bellezza 2008, p. 90 (fig. 150). Human bones were extracted from this open structure in 2002 for radiocarbon analysis.

Fig. 27. A tomb comprised of several vertical courses of masonry (FS5). Perched on the edge of a gully, this tomb was exposed some years earlier by running water. Human bones are no longer visible on the surface of the structure.

Three funerary structures close to one another are situated 360 m east of FS5, at the foot of the enclosing ridge. The two smaller specimens are highly fragmentary (FS6, FS7). The larger and somewhat better preserved one (FS8) measures 4.5 m by 4.5 m and is not aligned in the cardinal directions.* It is composed of stones 20 cm to 60 cm long.

This funerary structure is designated FS3 in Bellezza 2014b, p. 134.

Fig. 27a. Traces of human bones in situ in FS5. Photographed in 2002.

Fig. 28. Funerary structure FS8.

Another funerary enclosure (FS9) is situated on the rim of the esplanade, 120 m east of FS8.* The single-course perimeter walls of this square structure are only minimally intact (they are not aligned in the cardinal directions). This structure measures 6.8 m x 6.8 m. There may possibly be structural elements within the perimeter walls. The slabs of the perimeter walls are up to 40 cm in length and rise as much as 25 cm above the surface.

In Bellezza 2014b, p. 134, this funerary structure is designated FS4.

Fig. 29. The quadrate funerary enclosure FS9 viewed from the west. Note the partially intact perimeter walls and raised center of the structure.

Quadrate funerary structure FS10 is located 88 m west of the temple-tomb of the Central Complex. This quadrate structure is set near the rim of the esplanade and is generally aligned in the cardinal directions. It measures 4.6 m (north-south) by 3.9 m (east-west) and is composed of single-course perimeter walls. The stones in these walls are 30 cm to 75 cm long and protrude a maximum of 30 cm above the surface.

Fig. 30. Quadrate funerary enclosure FS9 viewed from the north. Portions of all four perimeter walls can be seen.

Funerary enclosure FS11 is situated near the edge of the esplanade, 34 m southwest of the temple-tomb of the Central Complex. No coherent wall segments remain intact. This structure is covered in stones embedded in the ground and approximately measures 4.4 m by 3.3 m. Its center is elevated 30 to 40 cm above the surface. There are scant structural remains (FS12) situated 3–7 m west of FS11.

Fig. 31. Vestiges of funerary structure FS11 with the Central Complex of TBRH in the background below the ridge.

Central Complex

The temple-tomb and array of stelae of the Central Complex of TBRH are aligned in the cardinal directions (within a few degrees of dead reckoning). The temple-tomb measures 6.1 m (north-south) by 3.6 m (east-west). The exterior south and west walls attain a maximum height of 2 m. The north wall is up to 1.6 m high and the east wall 1.8 m high. Given its relatively diminutive dimensions, the original elevation of the building may not have been much more than its current maximum extent. This edifice, or at least its south side, appears to sit on a plinth. This underlying structure compensates for the gentle declivity of the esplanade at the site of construction.

Fig. 32. The array of stelae and appended temple-tomb of the Central Complex as seen from the east.

Fig. 33. The concourse of standing stones and temple-tomb of the Central Complex from the northwest.

Fig. 34. The south wall of the temple-tomb, Central Complex. Note how this standing wall is primarily constructed of slabs.

Fig. 35. The temple-tomb and recently vandalized east wall, Central Complex. Much of the east wall was destroyed by excavation. Several tons of rubble were disgorged from the interior of the edifice by grave robbers. The river running through the valley hugs the base of the esplanade below the Central Complex.

In 2002, the temple-tomb of the Central Complex was the best preserved of the three at TBRH. Sadly, sometime after that, it was seriously damaged by looters. The east/forward wall was smashed and the south half of the interior excavated to a depth of 1.8 m. The compromised east wall may soon collapse unless action is taken to stabilize it. Unbeknownst to the grave robbers, they were removing impacted rubble from the structure, not integral building materials. It is unlikely therefore that they found much of value and the excavation was halted before the temple-tomb was half emptied of rubble. The stones and earth filling the interior of the temple-tomb appear to be part of a much earlier pillaging of the site, perhaps during the widespread desecration of such monuments, either with the annexation of Upper Tibet by the Tibetan empire in the mid-7th century CE or with the empire’s collapse in the mid-9th century CE. As with all forty-four temple-tombs in the region, after valuables were removed they were left open to deteriorate in the elements. The spread of Buddhism and its alternative eschatological doctrines are likely to have played a role in the destruction of these sites.

At some point in time, the temple-tomb of the Central Complex was refilled with stones and earth, most of which presumably came from the structure itself. The recent illicit excavation of this edifice reveals a clean cross-section of the east wall, a well-built double-course masonry structure 65 cm in thickness. Fourteen vertical courses of the south wall are also exposed, having a total height of 95 cm. The east and south walls are constructed of roughly hewn slabs 15 cm to 30 cm in length. The west or rear wall of the central chamber was also exposed by the excavation. It has a coarser fabric and is somewhat thicker than the east wall. There is no evidence of inner walls surrounding the central chamber nor of a partition bisecting it. We can infer then that the single chamber measured around 4.8 m (north-south) by 2.2 m (east-west).

Fig. 36. The east and south walls of the temple-tomb, Central Complex. The rubble piled against the structure came from the destroyed portion of the east wall and the interior of the edifice.

Fig. 37. The exposed east wall of the temple-tomb and excavation, Central Complex. This wall was adeptly constructed of slabs. The earth and stones removed from the center of the structure are fill added to the ruin sometime in the past.

Fig. 38. Excavation of the temple-tomb of the Central Complex. The wall at the bottom left corner of the image is a portion of the east/forward wall. The wall in the upper middle part of the image is the rear/west wall.

Measured from the eastern edge of the temple-tomb, the array of stelae is 47 m long (east-west). However, the first stele in situ is planted 11.2 m east of the east wall of the edifice. The array is approximately 13.9 m wide (north-south). There are only eighty-two stelae still standing, rising 15 cm to 65 cm above the surface. There are also twenty-seven fallen specimens among them, 25 cm to 1 m long. These counts illustrate the highly fragmentary state of the concourse of stelae. More than 80% of the original number are missing. The larger standing stones tend to be tabular and are concentrated near the east end of the array. Originally, there may possibly have been around twenty-two rows of stelae.

Fig. 39. The array of stelae from atop the temple-tomb, Central Complex. Most of the standing stones have long since disappeared. The temple-tomb of the East Complex is visible in the background.

Fig. 40. A close-up of some of the stelae in the array of the Central Complex. Note how most of these standing stones have a tabular form.

East Complex

The East Complex of TBRH begins 165 m east of the eastern extent of the Central Complex. There are only expansive views in the east from this sector of TBRH. The concourse of stelae gently declines towards the east, probably due to geomorphological changes to the terrain that occurred after the building of the monument.

The temple-tomb measures 7 m (north-south) by 3.4 m (east-west). On the south side of the edifice is an intact wall segment composed of nine vertical courses of slabs with a total height of 80 cm. The east wall is up to 70 cm high and comprised of seven vertical courses of slabs. The north wall is reduced to 40 cm in height (four vertical courses) and the west wall is 30 cm high (four vertical courses). These walls probably coincide with the lower section of the central chamber. However, no signs of the central chamber are visible and the current top of the temple-tomb is highly eroded. Since 2002, three holes up to 70 cm deep were dug in it; no doubt, in the search for valuables. This edifice appears to rest on a plinth but only a small portion of it is visible. This plinth (approximately 9 m x 6.2 m) adds 50 cm to the height of the north side of the temple-tomb, 75 cm to the east side, 1 m to the west side and 55 cm to the elevation of the south side. This structure created a level platform for the erection of the freestanding walls of the superstructure.

Fig. 41. The array of stelae and appended temple-tomb of the East Complex seen from the northeast. The two broad sides of stelae tend to be oriented north and south.

Fig. 42. The array of stelae and appended temple-tomb of the East Complex seen from the southeast.

Fig. 43. The west half of the array of stelae and temple-tomb of the East Complex.

Fig. 44. The south wall of the temple-tomb, East Complex.

Measuring from the east edge of the temple-tomb, the array of stelae is 26 m (east-west) long. However, the first standing stone in situ is located 5.7 m east of the temple-tomb and the two most easterly erect stelae are situated 3.5 m east of the rest of the array. This concourse of standing stones is approximately 12.5 m wide (north-south). It is highly disturbed and eroded and around 75% of all stelae are now missing. There are nearly 200 stelae still anchored in the ground and eighty-five fallen ones amongst them. Most of the standing stones rise 25 cm to 50 cm above the surface. However, there are also many broken specimens 20 cm or less in height. The prostrate examples are between 25 cm to 60 cm in height. The tallest stele still standing is located near the southeast corner of the array (85 cm high x 45 cm wide x 18 cm thick). There appear to have been around twenty-three rows of stelae in the array.

Fig. 45. The East Complex viewed from the northwest. Most of the temple-tomb is now in ruins.

Fig. 46. The East Complex viewed from the south.

Fig. 47. A view of the array of stelae of the East Complex from a southwestern perspective.

Fig. 48. The concourse of stelae as seen from the top of the appended temple-tomb, East Complex. In the background is the eastern horizon.

Fig. 49. A close-up of stelae in the array of the East Complex. The broad sides of the tabular stelae face north and south.

Fifty-three meters northwest of the temple-tomb of the East Complex are six or seven slabs in situ, remnants of another funerary structure (FS13). The largest of these stones is made of conglomerate and is 65 cm long, 40 cm wide and 7.5 m thick.

Fig. 50. Stones protruding from the ground marking the site of another funerary structure (FS13) at TBRH.

Dating Talus-blanketed Red House

Two phalanges collected from funerary structure FS5 of TBRH, in 2002, have undergone AMS analysis. These two human bones and others belonging to the same burial were discovered on the surface of the tomb in which they were deposited after it was cut open by a torrent. This natural event is reported to have occurred not much before the first survey of TBRH in June 2002. The two phalanges were still integrated in the burial at the time of collection but were in imminent danger of being washed away. Since that time human remains have disappeared from the top of tomb.

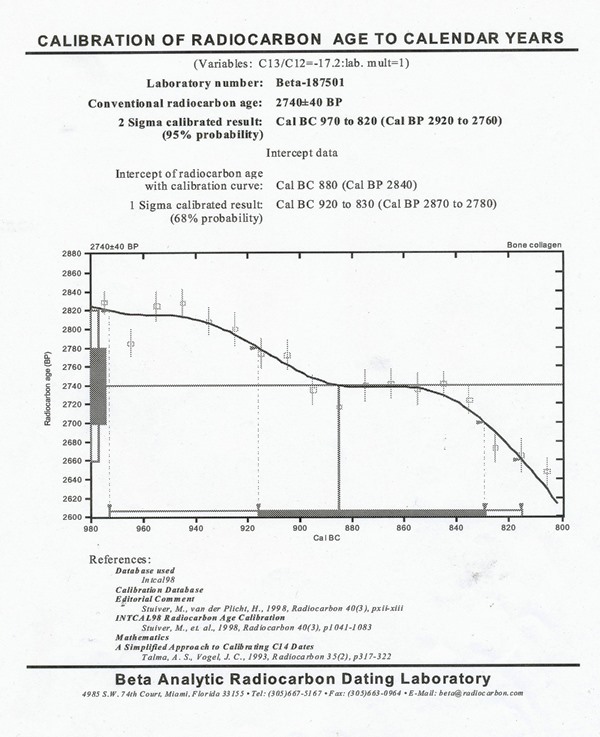

Fig. 51. Data sheet detailing the AMS analysis of human bones from funerary structure FS5, TBRH.

The results obtained from the AMS assay of FS5 are the single best indication of the age of elements of the TBRH necropolis, indicating that, at least in part it, was established in the 10th or 9th century BCE. The AMS assay of the human bone sample was carried out by the Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Dating Lab in Miami (sample no. Beta-187501). The results were calibrated as per recognized scientific protocols. The sample yielded a calibrated radiocarbon age of circa 970–820 BCE.*

The conventional radiocarbon age is 2740 +/- 40 BP (Before Present; calculated from 1950 CE); 2 Sigma calibrated result (95% probability): 2920 to 2760 BP; intercept of radiocarbon age with calibration curve: 2840 BP; and 1 Sigma calibrated result (68% probability): 2870 to 2780 BP.

The dated sample from FS5 was salvaged from the surface and no attempt was made to probe subterranean aspects of the structure, thus the mode of burial represented by the human foot bones is unclear. It can be assumed that the age of the bones collected can be applied to the remainder of the inhumation and tomb in general. Small burial structures are less likely to contain sequential primary burials and foot bones are less common in fractional burials. As detailed above, thirteen outlying funerary structures have been pinpointed at TBRH. Tombs and non-sepulchral funerary structures are likewise regularly found at other stelar necropolises in Upper Tibet. Clearly, there was a tradition of situating underground tombs and ritual structures near the stelae and temple-tombs and, most frequently, in direct view of them.

The chronological profile of the constituent elements of TBRH has not been determined with any assuredness. Nevertheless, the spatial organization of the site provides us with some clues. FS5 is interjacent to the West and Central complexes. Such outlying funerary structures are situated near ravines, on the edge of the esplanade, or on more sloping ground beside the foot of the enclosing ridge. On the other hand, the three arrays and temple-tombs were built on level, open ground in central locations along the esplanade. The placement of the arrays of stelae and appended tombs on the most even and stable terrain and the peripheral nature of surrounding funerary structures suggests that the latter are subsidiary elements of the site, which were founded at the same time or after the key monuments as the cemetery expanded. It appears therefore that one or more of the arrays of stelae and appended temple-tombs can be attributed to the same period or perhaps somewhat earlier than FS5; i.e. 10th or 9th century BCE. This estimation of age, however, may possibly be relevant for the West Complex only, which is closest to FS5. The West Complex is on the west and more open end of the TBRH site and has the deepest views to the east. These spatial characteristics are more in conformance with other sites of stelar necropolises than are the locations of the Central and East complexes. This may possibly signal that the West Complex was the first of the three examples to be built at TBRH.

Inferring the age of the arrays of stelae and appended temple-tombs at TBRH from a single calibrated date can be risky business, yet it is the best indication we have at present.* As we shall see in Part 2 of this article, a Final Bronze Age periodization for the site is supported by comparison with better-studied funerary monuments in north Inner Asia. How long stelar necropolises were built and used, or how their functions might have changed over the centuries are pending questions. Given the very particular high elevation environment of Upper Tibet, its highly insulated geographic quality, and its peculiar and limited range of archaic monuments, it may eventually be shown that the stelar necropolises continued to be built over a wide time span. If so, there are monumental analogies in north Inner Asia; e.g., slab graves of the Final Bronze Age and Iron Age. It is very unlikely, however, that these highly distinctive monuments (nothing like them is found in other regions of Tibet or in adjoining territories) were constructed after the annexation of Upper Tibet by the Central Tibetan empire in the mid-7th century CE. Furthermore, the use of stelar necropolises as burial sites and places of funerary ritual observance and other cult practices can hardly be expected to have survived the vigorous spread of Buddhism in Upper Tibet in the 11th century CE.

To refine our understanding of the origins, development and demise of TBRH more chronometric data are demanded. This will only come about through scientific excavation and the collecting of more organic samples in situ. This is a difficult prospect given the current overall climate in the TAR and the resistance on the part of the authorities to significantly expand archaeological exploration in Tibet. Moreover, TBRH cannot be studied in isolation: it must be examined in association with the other 30 sites of the same typology documented in Upper Tibet by the author.

Geographical, ideological and sociopolitical characteristics of Talus-blanketed Red House

TBRH is one of thirty-one sites with stelar necropolises distributed over a 250,000 km² swathe of Upper Tibet. In addition to the actual places they occur, the uninhabited tracts of the northern Changthang belong to the same cultural and physical province. The stelar necropolises are not the only areal indicators of this territory. They share space with several other types of archaic (pre-Buddhist) monuments. These include funerary enclosures of various kinds and residential structures built exclusively with corbelled roofs and stone building materials.* It appears that these all-stone corbelled structures functioned as temples, hermitages, fortresses and palaces.†

For a description of the typological, morphological, functional, chronological and cross-cultural traits of archaic residential and ceremonial monuments in Upper Tibet, see Bellezza 2001; 2002; 2003; 2008; 2011; 2014a; 2014b; 2014c; 2015.

Thus far, the oldest all-stone corbelled residential structure known in Upper Tibet, as determined through radiocarbon analysis of associative organic traces, is a building at the Gekhö Kharlung (Ge-khod mkhar-lung) castle in Ruthok. A small round of wood recovered from a semi-subterranean dependency at this site has yielded a calibrated date of 200 BCE to 100 AD. See Bellezza 2008, pp. 36, 37; 2014a, pp. 138–144; 2014c, pp. 118, 120, 121, 134. It is, of course, possible that the main parts of Gekhö Kharlung are even older. We simply do not know. Nevertheless, the occurrence of well-built, free-standing masonry structures at TBRH, indicates that Upper Tibetans had perfected the designs and methods for constructing relatively large freestanding edifices in the early first millennium BCE. The specialized building techniques being employed enabled the corbelling of roofs and the raising of load-bearing walls of significant elevation.

The distribution of funerary enclosures mimics that of the stelar necropolises. So, too, all-stone corbelled residential structures; however, these are also found west of the territorial extent of the necropolises in the badlands of Guge (Gu-ge). Mountain-top cubic tombs, another archaic monument in Upper Tibet, have a more restricted distribution within the territorial ambit of the stelar necropolises.* Although these residential and funerary monuments share the same territory as the stelar necropolises and are culturally and architecturally related to one another, their respective chronological development is still largely undetermined.

Another type of monument closely conforming to the geographic distribution of the stelar necropolises is stelae erected inside quadrate enclosures. These walled-in stelae also had a funerary function, as demonstrated by tombs and other funerary structures configured around them. Both types of stele monuments in Upper Tibet appear to be closely related functionally and chronologically. In fact, these two monuments are joined together in one integral complex at Doring, in the old district of Namru (Bellezza 2014b: 178–182). This site was first visited by the Russian explorer George Roerich in 1928.

To date, I have documented the existence of 98 walled-in stelae sites, thus they are more than three times as numerous as the stelar necropolises. In general, walled-in stelae represent less ambitious construction projects than the stelar necropolises, requiring fewer resources and labor to build and maintain. Stelae erected inside quadrate enclosures possess geographic settings comparable to the stelar necropolises: they are located on open, level ground that is well drained and isolated from open sources of water. They are also positioned with long views to the east and much more constrained views in the west.

Fig. 52. Artist’s conception of stelae standing inside a double-course slab wall enclosure (after Bellezza 2014a, p. 10). Typically, one or more stelae was planted near the west wall of a quadrate enclosure. In some examples, there is an opening in the east wall of the enclosure.

Fig. 53. Geographic distribution of the walled-in stele monuments (after Bellezza 2008, p. 737; 2014b, p. 629). Although more numerous than the stelar necropolises, both types of monuments occupy the same territorial range.

The stelar necropolises and stelae erected inside enclosures serve as sui generis markers delineating a contiguous territory in Upper Tibet with common funerary traditions. When these and other kinds of archaic monuments are considered in association with the corpus of contemporaneous rock art in the same region, a unique archaeological culture emerges. The material aspects of this culture are defined by an especial repertoire of monuments and rock art as well as the artefactual record. This archaeological culture sat squarely in the central and western Changthang and Tö to the west; i.e., most of Upper Tibet west of the 89th meridian.

The material traces found in the ‘core’ region of Upper Tibet correlates with what was once a living culture, complete with economic foundations, political organization, social institutions, interpersonal bonds, technological capabilities, ideological patterns, and a symbolic universe. How this culture of the Final Bronze Age changed or was replaced over time is unclear. Chronological markers for the Iron Age and Protohistoric period are still scant in Upper Tibet, obscuring questions of cultural continuity, interruption and transformation.

As the cultural and ethnic development of Upper Tibet from the end of the Bronze Age to the beginning of the historic era are hazy, it is difficult to effectively apply traditional Tibetan ascriptions to the archaeological records of the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age and Protohistoric period. Old Tibetan historical documents state that a kingdom called Zhang Zhung existed in western Tibet in the early 7th century CE. The later literature of Bon, a minority lamaist religion of Tibet, tends to extend the historical and geographical scope Zhang Zhung but the more grandiose claims made are likely to have little veracity. Old Tibetan literature also notes several ancestral attributions for Upper Tibetan peoples and territories, but how these toponyms and ethnonyms can be applied to the pre-Buddhist (pre-7th century CE) archaeological evidence is questionable. In the oral tradition of Upper Tibet, the stelar necropolises and other archaic monuments are often associated with the Mon, a nebulous ethnic and historical group.* It can be concluded, therefore, that none of the traditional attributions for the Upper Tibetan territory, culture or polity of antiquity are suitable as archaeological nomenclature unless amended by specific geographical, material and chronological data.†

According to the oral tradition of Changma and Gertse (location of TBRH), there were two ancient groups in those regions: Mon and Byang-ba ha-shes. These groups are thought to have been related to one another and to have disappeared long before Tibetan herders arrived in the area. The addition of “Northerner” (Byang-ba) to Byang-ba ha-shes and the non-Tibetan etymology of the second element of the name (Ha-shes) suggests that this ethnonym refers to a people of north Inner Asian origin. See Bellezza 2014b, p. 132 (n. 1). The historical pedigree of this term, however, is unknown.

On questions concerning the use of traditional Tibetan historical and cultural ascriptions in an archaeological nomenclature, see Bellezza in press.

The architectural and locational qualities of the temple-tombs strongly suggest a non-residential function. However, their mortuary, ritual and symbolic functions remain enigmatic. There is still no direct evidence that the central chamber(s) of these edifices functioned as tombs, however, no attempt was made during my surveys of surface remains to probe beneath debris. As noted, the chambers are enclosed in thick walls without windows, doors or other openings in the walls. Moreover, the stelar necropolises are situated in plains and other open areas that are easily accessible. By contrast, archaic residential structures were usually stationed on summits, couloirs, hidden amphitheaters and other high ground that is to some degree or another protected and hidden. Traces of some ancient settlements are set in more open areas but their footprint is of an entirely different order (they are composed of clusters of dwellings, agricultural structures, etc.).

Although all relevant archaeological monuments must be considered when defining the pre-Buddhist cultural complexion of Upper Tibet, this work is specifically concerned with the stelar necropolises and what they might say about the lifeways and environment of the region at the end of the Bronze Age. As we have seen, TBRH furnishes evidence to indicate that by the 10th or 9th century BCE, the inhabitants of Upper Tibet had mastered advanced building skills used to construct intricate necropolises for burial and ritual activities. Only further archaeological exploration (including investigation of subsurface aspects of sites) will permit us to reconstruct the manner of burial and the nature of the ritual, ceremonial and commemorative exercises connected to the stelar necropolises. In lieu of that, I offer some preliminary observations concerning their cult functions, symbolism and significance.

The erection of concourses of standing stones carefully laid out in a grid pattern aligned in the cardinal directions clearly shows that these sites functioned as more than mere utilitarian depositories of human remains. The wide vistas to the east suggest that the rising sun played a role in the ritual dispensations and eschatological beliefs of the builders and users of the stelar necropolises. The regenerative symbolism of the sun is widely known in world mythology and religion. The orientation of the stelae and temple-tombs in the cardinal directions also suggests that astronomical calculations played a part in their establishment and ritual use. The alignment of structures could possibly have been harnessed to make planetary and sidereal sightings relevant to the funerary traditions of that time. In some Old Tibetan literature (composed 8th to 10th century CE), the sky, sun and moon and stars feature in funerary myths and ritual procedures (Bellezza 2008; 2013). However, it is not certain in what ways the funerary activities and lore of the texts are germane to the much more ancient necropolises under study. The relevance of the archaic funerary documents to an understanding of the archaeological evidence pivots on the continuity of mytho-religious themes and motifs over a period of no less than 1600 years.*

For an examination of areas of correspondence between Tibetan funerary ritual documents and pre-Buddhist funerary monuments and artifacts of Upper Tibet, see, for example, Bellezza 2008, pp. 543–557; 2013, pp. 157–159; 2014c, pp. 153–160; November 2013 and March 2016 Flight of the Khyung.

There are various references to registers (tho) in Tibetan funerary literature, some of which is composed in the Old Tibetan language. The main purpose of tho in ritual texts is as receptacles of the souls of the deceased; these were erected during evocation rites designed to guide them to the afterlife. If these tho are related to the funerary stelae, as local folklore suggests, the standing stones may have had a specialized ritual function related to the valediction of souls. One 10th century CE text, Klu ’bum nag po, treats the tho as objects that could be walked through or around during a funeral (Bellezza 2008: 483, 484, 489).

Archaic funerary rites preserved in Tibetan literature indicate a ubiquitous belief in an afterlife and the power of funerary priests to help the deceased reach there. The texts also make clear that the funerary rites were intended to inoculate the living from premature or accidental death in the wake of the untoward passing of others. These fundamental themes (eschatological, psychopompic and protective) are likely to underpin ritual aspects associated with the stelar necropolises, even if these were articulated in ways differing from the textual accounts (none of which were written prior to the 8th century CE).

The religious function, if any, of the sacred mountain She Kangjam is a moot point. While it is likely that this prominent massif in sight of TBRH was incorporated in the mythology and sacred geography of the people who built and used the stelar necropolis, it is unclear whether it was directly involved in ritual activities conducted at the site. Some places with stelar necropolises are not directly in sight of lofty snow mountains. Nevertheless, Old Tibetan funerary ritual texts contain references to the paradisiacal qualities of high mountains. For example, the otherworld is sometimes referred to as the ‘joyous mountain’ (dga’-ri).

While ideological, ritualistic and symbolic elements connected to the cultic use of the stelar necropolises remain opaque, sociopolitical, technological and economic processes associated with them are somewhat more amenable to analysis. The construction of these monuments required considerable labor including skilled craftsmen. These workers needed to be fed and otherwise supported. Four of the thirty-one sites of stelar necropolises are situated within 40 km of agricultural enclaves, but it has not yet been determined if any of these areas were being tilled at the end of the Bronze Age. It is certainly possible though that the wider agro-pastoralist economy of lower elevation far western Tibet and Lake Dangra in the Central Changthang may have played a part in the establishment of the stelar necropolises.

The other twenty-seven stelar necropolises are in regions far from farming enclaves, where nomadic pastoralism (Bodic variety) appears to have been a basis of the local economy. Given the extremely high altitude of these sites, they are likely to have depended primarily on yak, goat and sheep pastoralism 3000 years ago, just as they do today. Nonetheless, these regions did not necessarily have the same brand of nomadic pastoralism as seen in more recent times. There may have been considerable differences in the makeup of the pastoral economy at the end of the Bronze Age, reflecting a varied climatic, environmental, sociopolitical and cultural regime.

Upper Tibetan rock art indicates that the hunting of wild yaks, deer and wild caprids was an important activity for a segment of the male population in the first millennium BCE. Thus, hunting may have also contributed to the economic sustenance of regions with stelar necropolises. Trade in wild animal skins and other animal products derived from hunting and livestock rearing such as musk, cheese and wool, and the exploitation of minerals such as gold, turquoise, borax and salt may have added to the wealth needed for the construction of the stelar necropolises as well.

However wealth was generated in the form of food and other essential goods and trade items, surpluses were essential in the maintenance of the workforces involved in the construction of the necropolises and in their upkeep and ritual usage.

The creation of the stelar necropolises was predicated on the organization of individuals into coherent and effective workforces. This may have entailed the imposition of a leader, the appointment of advisors or spiritual preceptors, architects and supervisors overseeing the work, managers in charge of logistic operations, and possibly even emissaries charged with marshalling support for the project. Trained masons and an ample supply of laborers were of course essential to the project. Cooks, hunters, shepherds, artisans, medics, priests, astrologers, cleaners and those with sundry other skills may also have been part of the effort.

The thirty-one stelar necropolises delineate a coherent cultural sphere spread over an area of 250,000 km² (adjacent tracts to the north notwithstanding), which developed at the end of the Bronze Age. Implicit in the establishment of these necropolises is a high level of cultural communications, informing the development of an integral body of customs, traditions, beliefs and cult practices over the entire region in which they were built. However, these sites in themselves tell us little about the political makeup of the territory at the end of the Bronze Age.

The nature of the Upper Tibetan polity and its organs of political coordination had a huge bearing on how the stelar necropolises were built and used. The dozens of archaic fortresses and castles in the same territory, some of which may be of comparable antiquity, suggest a strong martial component in the dispensation of political power. However, it is not known how power and authority issuing from strongholds at the end of the Bronze Age may have been exercised over the communities of farmers and herders in their midst. A paucity of archaeological evidence forces us to consider the matter in broad and inexact terms.

Whatever kind of political dispensation existed in Upper Tibet at the end of the Bronze Age, a good deal of sociopolitical integration seems to underlie the establishment of the stelar necropolises, for they are distributed over a very large territory. To muster the labor and expertise required to build the necropolises, people probably traveled over relatively long distances to reach the sites. This implies the existence of an effective communications and transport system based on coordinated relations between dispersed communities. The Changthang is an extremely harsh environment that never supported high population densities nor urban settlement prior to the modern period. As in more recent times, most of its ancient communities were rural-based. At lower-elevation Lake Dangra, in the central Changthang, and in far western Tibet, some early communities may have been citadel-based. However, most stelar necropolises are not located near important pasturelands or castles, areas that potentially enjoyed higher population densities than surrounding areas.

The degree of hierarchical division and occupational specialization among the various participants in the construction of the stelar necropolises is debatable. I will briefly set out three political scenarios and outline how these may have encouraged the creation of stelar necropolises. If there was a unified polity, kings or an aristocracy may have ruled, those possessing much influence or even direct control over the establishment of the various stelar necropolises. A looser polity consisting of a confederacy of autonomous regions or tribes could have relied on a coterie of chieftains or councils of elders. This kind of political system may have pitted regions against one another, spurring on the construction of stelar necropolises defined along geographical and tribal lines. If political power was more heavily decentralized in localized clan or tribal structures, various communities may have enjoyed a high level of autonomy. In that case, significant consensual or republican structures at the local level may have played a major role in the creation and maintenance of the stelar necropolises. A high level of egalitarianism, should it have prevailed, would have given rise to corporate enterprises involving persons sharing common aims and aspirations.

It is not known how many stelar necropolises were actually built. Their current spotty distribution patterns suggest that there may have been many more than the thirty-one documented. Nevertheless, it does not appear that they ever existed in large numbers. These necropolises were not pedestrian monuments (among them are some of the largest and most complex archaic structures in Inner Asia); rather they appear to have been elite centers where high status activities connected to the burial and honoring of prominent individuals transpired. Burials at the necropolises could only have accommodated a small segment of ancient society, a social and economic distinction reserved for select individuals. This seems to imply that robust sociopolitical hierarchies were in operation. If so, the building of the necropolises may have been legally binding or even coercive affairs, not the fruits of a more egalitarian tribal society. At this preliminary stage of research, it is uncertain which of the scenarios I have outlined is more in conformance with ancient sociopolitical realities in Upper Tibet.

The stelar necropolises, specifically TBRH, furnish the earliest evidence in Upper Tibet for cultural, sociopolitical and technological complexity associated with foundations of civilization elsewhere in Inner Asia. Talus-blanketed Red House serves as a chronological benchmark for interrelated archeological evidence uncovered in Upper Tibet, positioning this seminal stage in the development of the region to the end of the Bronze Age. Through the monuments, rock art and artifacts reviewed in this article, a fuller picture of the genesis of civilization on one part of the Tibetan Plateau has emerged. This evidence, however, should not be viewed in isolation. It is part of an unfolding cultural and technological legacy, informing subsequent developments in the Iron Age and Protohistoric period. The monumental, rock art and artefactual assemblages of Upper Tibet demonstrate continuities in form, style and subject matter, tracing the trajectory of pre-Buddhist civilization on the loftiest reaches of the Tibetan Plateau.

Bibliography

Bellezza, John V. In press. “Discerning Bon and Zhang Zhung on the Western Tibetan Plateau: Designing an archaeological nomenclature for Upper Tibet, Ladakh and Spiti based on a study of cognate rock art”, for International Conference of Shang Shung Cultural Studies Beijing, September 18–21, 2015.

_____2015. “The Ancient Corbelled Buildings of Upper Tibet: Architectural attributes, environmental factors and religious meaning in an unique type of archaeological monument” in “Architecture and Conservation: Tibet”, November 2015 (ed. Hubert Feigelsdorfer) pp. 4–19. Journal of Comparative Cultural Studies in Architecture. Special issue from proceedings of the International Association of Tibetan Studies XIII, Ulan Bator.

http://www.jccs-a.at/system/resources/W1siZiIsIjIwMTUvMTEvMjUvMTRfMzRfMzBfNDAwXzAyX0JlbGxlenphLnBkZiJdXQ/02_Bellezza.pdf

_____2014a. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Residential Monuments, vol. 1. Miscellaneous Series – 28. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version, 2011: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org). http://www.thlib.org/bellezza

_____2014b. Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Ceremonial Monuments, vol. 2. Miscellaneous Series – 29. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version, 2011: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza.

_____2014c. The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

_____2013. Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet: Archaic Concepts and Practices in a Thousand-Year-Old Illuminated Funerary Manuscript and Old Tibetan Funerary Documents of Gathang Bumpa and Dunhuang. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 454. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

_____2011. “Territorial Characteristics of the Pre-Buddhist Zhang-zhung Paleocultural Entity: A Comparative Analysis of Archaeological Evidence and Popular Bon Literary Sources”, in Emerging Bon: The Formation of Bon Traditions in Tibet at the Turn of the First Millennium AD (ed. H. Blezer), pp. 51–116. PIATS 2006: Proceedings of the Eleventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Königswinter 2006. Halle: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies GmbH.2008. Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet. A Historical and Ethnoarchaeological Study of the Monuments, Rock Art, Texts and Oral Tradition of the Ancient Tibetan Upland. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse Denkschriften, vol. 368. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

_____2005. Calling Down the Gods: Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet, Tibetan Studies Library, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill.

_____2003. “Bringing to Light the Forgotten: Major Findings of a Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites in Upper Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region, Peoples Republic of China). Conducted Between 1992–2002” in Athena Review, vol. 3 (4), pp. 16–26. Westport.

Chinese language version: Xunzhao Shiluo De Wenhua: “Xibu Xizang Qian Fujiao Shiyi Zhongyao Kaogu Yiji Diao Cha Baogau” (trans. Tang Huisheng and Tan Xiuhua) in Essays on the International Conference on Tibetan Archaeology and Art, pp. 1–29. Chengdu: Sichuan Remin Chuban She, 2004.

_____2002. Antiquities of Upper Tibet: An Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Sites on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

_____2001. Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

Don – Grub Lha – Gyal (Don-grub Lha-rgyal). 2003. “Introduction to the Cultural Heritage of the Zhang Zhong Kingdom in the North of Tibet” in Tibetan Studies, vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 93–108. Lhasa: Tibetan Academy of Social Sciences.

Fitzhugh, William, F. 2015. The Mongolian Deer Stone-Khirigsuur Complex: Dating and Organization of a Late Bronze Age Menagerie”, in Bronze Age Mongolia (ed. J.-L. Houle), pp. 183–189. Oxford Handbooks Online:

http://www.eastwestcenter.org/sites/default/files/filemanager/ASDP/NEHMongol2014/FitzhughGermanSymp183-199.pdf

Honeychurch, William. 2015. Inner Asia and the Spatial Politics of Empire: Archaeology, Mobility, and Culture Contact. New York: Springer.

Huo Wei. 2005. “A Study on the Archaeology of the Early Civilization of Western Tibet” in, Tibetan Studies, vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 43–50. Lhasa.

Next Month: Upper Tibetan necropolises in the greater scheme of things!