November 2015

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another Flight of the Khyung as we continue our explorations on the western fringes of the Tibetan Plateau! This issue presents the last in a three-part article surveying the rock art of Spiti. There are many more intriguing images of both ancient carvings and paintings for your inspection in this comprehensive examination of Spiti’s rock art. Like so many other articles featured in these newsletters, this is something you will not find elsewhere.

A Survey of the Rock Art of Spiti – Part 3

Please see the September and October 2015 Flight of the Khyung newsletters for the first two parts of this article. For a comprehensive review of rock art in Spiti see the July 2015 newsletter. For cultural and historical links between the rock art of Upper Tibet and Spiti, see the August 2015 newsletter.

In this third and final part of the article the following Spitian rock art sites are covered:

Petroglyphs

- Jomo Phuk (Jo-mo phug; el. 3735 m)

- Pheldar Thang (’Phel-dar thang; el. 3950 m)

- Dungma Dangsa (mDung-ma brang-sa; el. 4115 m)

- Taktse (sTag-rtse?)

Pictographs

- Kubum (sKu-bum; el. 4315 m)

- Thonsadrak (mThon-sa brag; el. 3630–3660 m)

- Nyima Loksa Phuk (Nyi-ma log-sa phug; el. 4330 m)

- Sinmo Khadang (Srin-mo kha-gdang; el. 4720–4740 m)

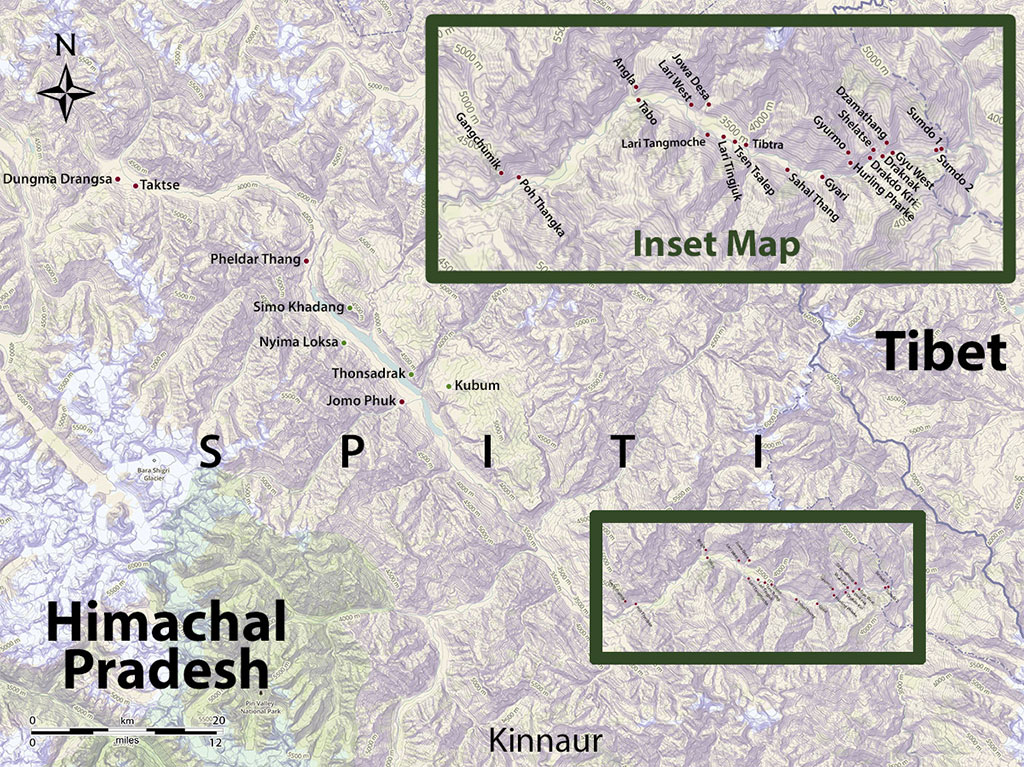

The rock art sites of Spiti: red dot denotes petroglyphs, green dot denotes pictographs. Map by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza. Click to enlarge.

Jomo Phuk

The rock art site of Jomo Phuk is situated several kms upstream of Kaza, the capital of Spiti. This sacred cave shelter overlooks the confluence of the stream at Rangthang (Rang-thang) and the Spiti River. The cave is suspended about 30 m above the side stream. It is here that a number of engraved chorten (mchod-rten) dating to the 11th or 12th century CE is found.

It is said that a long time ago a nun lived in Jomo Phuk. In the local oral tradition she gave birth to a son without a man, suggesting that the father was a divinity (folktales of women knowingly or unknowingly consorting with deities such as mountain gods and giving birth to sons are quite common in the Tibetan world). That this nun had a child out of wedlock caused her family great shame and she was forced to leave home, finding shelter in the cave, which is named after her. Her son was called Great Adept Rangrik Lama (sGrub-chen Rang-rigs bla-ma) and he is supposed to have grown up handsome and powerful, a sage who benefited many people.*

For a more detailed account of this folktale, see Thukral 2006, Spiti: Through Lore and Legend, pp. 80–82. New Delhi: Mosaic Books.

Fig. 21.1. A view of Jomo Phuk. Most of the rock engravings are located in the formation to the right of the cave.

Fig. 21.2. The defile around Jomo Phuk. The cave is located in the lower left half of the image behind the largest shadow. On top of the rocky knob to the right are the poorly preserved ruins of what is said to have been a Buddhist monastery.

Jomo Phuk is ensconced in a rocky defile. Inside the well-maintained cave are three holes overhead, which are said to be finger marks made when the ceiling was magically raised to create more headroom (probably by Great Adept Rangrik Lama). It is reported that the Sakya sect (Sa-skya-pa) has long used Jomo Phuk as a retreat. The ruins on the summit directly above this cave may possibly be the site of the first Sakya monastery in Spiti. It appears to have been destroyed by followers of the Kadampa (bKa’-gdams-pa) sect or their successors, the Gelukpa (dGe-lugs-pa) sect, before the founding of Key Gonpa (dKyil dgon-pa) in the 14th century CE. The existence of carved chorten at Jomo Phuk establishes that this site was indeed an early Buddhist religious center, circa 1000–1200 CE (taken as a whole, the stylistic features of the rock art suggest that it is more likely to date to the 11th century CE).*

The hilltop ruins above Jomo Phuk form a fairly sparse dispersion (20 m x 30 m) of rubble and depressions in the ground, all that presumably remains of a monastery. This site is strategically placed on the east end of the large agricultural flat of Rangrik. On the east side of the summit there is a highly eroded rammed earth wall fragment (2.4 m x 1.5 m) resting on a stone base. Remains also spill down the west side of the summit. Structural traces at the site exhibit uniform types of wall construction, suggesting establishment in the same period. There is a small prayer flag mast and cairns on the summit. In the limestone outcrops of the site are a number of circular holes that were used for grinding mineral or vegetable substances.

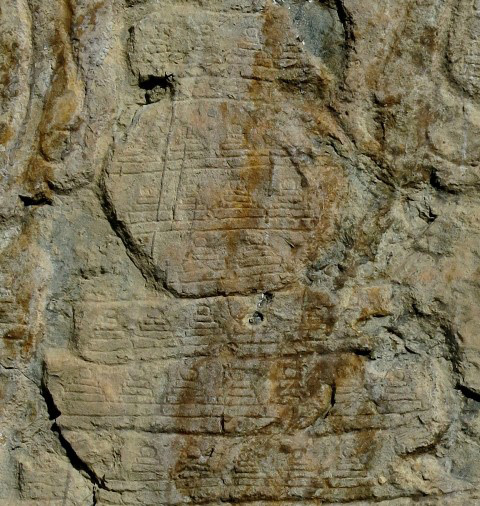

Fig. 21.3. The main panel of carved chorten at Jomo Phuk.

The carved chorten of Jomo Phuk are of significant historical and artistic value, augmenting evidence for the spread of Buddhism during the so-called second diffusion (bstan-pa phyi-dar). These rock engravings are located approximately 5 m above Jomo Phuk on a vertical rock face (2.4 m x 1 m) oriented south-southeast (160˚). On the beige-colored calcareous rock face are three large chorten (each 90 cm to 1 m in height) with numerous smaller specimens in and around them. These engravings were adeptly executed with much attention paid to overall form and decorative details, recalling a group of chorten of the same time-frame in Guge (see July 2014 Flight of the Khyung). The uniform style and carving techniques employed indicate that the Jomo Phuk specimens were all made around the same time and probably by the same hand.

A date of 1000–1200 CE for production for these chorten is indicated by the following set of stylistic and design features:

Prominent streamers (dar-thag) flanking the upper portion of the chorten

Cigar-shaped spires (’khor-lo)

Teardrop-shaped sun cradled in a crescent moon finial (tog)

Spireless chorten with only a platform as a crowning element

Two chorten sharing the same high base

The placement of rows of tiny chorten inside the round midsection (bum-pa) and tiered base (bang-rim) of larger specimens

Some of the stylistic and design traits noted above also characterize chorten of the early Historic period (650–1000 CE), but the overall form and character of these more ancient carvings are quite different. Early Historic period examples in Spiti are not as intricate as the ones from Jomo Phuk (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 21.4. The most northerly chorten, one of the three largest at Jomo Phuk. Note the base of five tiers and spire bisected vertically into two parts. The finial has largely worn away. It appears to have been in the same style as the large central chorten.

Fig. 21.5. The central specimen of the three largest chorten, Jomo Phuk. Note the thick streamers flanking the upper half of this carving. Much of the multi-tiered base has been obliterated. The upper five levels however are intact. There are rows of tiny chorten carved across each stage: platform below spire (one row), rounded midsection (three rows), five tiers of upper base (one row in each tier), and tiers of lower portion of base (three rows).

Fig. 21.6. The upper portion of the large central chorten, Jomo Phuk. Observe the teardrop-shaped sun and horn-like crescent moon finial. In between the streamers and spire are four small subsidiary chorten.

Fig. 21.7. Rows of tiny chorten inside the large central chorten. These subsidiary figures are around 5 cm in height.

Fig. 21.8. Lowermost row of subsidiary chorten in the large central chorten.

Fig. 21.9. The large south chorten, Jomo Phuk. This specimen appears to have the same type of finial as the other two large chorten but very little of it remains intact. The various stages of this monument are also filled with rows of subsidiary chorten: rounded midsection (four rows) and six tiers of base (one row in each).

Fig. 21.10. The base of the large south chorten. Note the the line of lotus petals at the bottom of the carving. These petals are angular and elongated, another stylistic clue as to the age of the carvings at Jomo Phuk.

Fig. 21.11. Chorten (43 cm high) of the same style situated between the large central and south specimens.

Fig. 21.12. Two spireless chorten in between the lower sections of the large central and south specimens. The larger of the twin chorten is 30 cm in height.

Fig. 21.13. Two spireless chorten sharing the same prominent base (20 cm in height). These are the southernmost carvings on the rock panel at Jomo Phuk.

Fig. 21.14. Two chorten below the large south specimen. They are each 5 cm in height. These are the lowest carvings on the rock panel.

Fig. 21.15. Two more rudimentary carvings of chorten (24 and 22 cm high) found on the ceiling of Jomo Phuk. Given their style, these chorten appear to have been made in the same time period as the carvings on the main panel.

Below the south side of the summit with the remains of the putative monastery, nine chorten were engraved in the rough-textured, brown-tinted calcareous rock. There are also faint traces of other chorten carvings on the same rock outcrop and on outlying rocks. Although more elementary in execution, these carvings were probably made in the same general period as those at Jomo Phuk. These two locations are situated approximately 150 m from one another and there is around a 20 m difference in elevation.

Fig. 21.16. A partial view of a row of six spireless chorten (each 35 to 50 cm high). Above this row of chorten is a much larger specimen. To the right of this larger specimen two chorten share a common base. These upper carvings are only partially visible in the photo.

Fig. 21.17. The large chorten partially pictured in Fig. 21.16, the top half of which has been destroyed. The remaining portion is 45 cm in height.

Fig. 21.18. The two interconnected chorten partially shown in Fig. 21.16. The sit upon a large base (45 cm x 20 cm).

Pheldar Thang

On a shelf above the Spiti river is a single limestone boulder with the carving of a chorten. This boulder is located near the enclosing ridge and due west of a pass that leads to the villages of Chichim and Kibbar, once a major route. Pheldar Thang also straddles a traditional as well as the modern route up the Spiti valley towards Kunzam La.

Fig. 22.1. Large, west-facing engraved chorten (1.85 m high), Pheldar. This chorten appears to be of significant age. In close proximity is the carving of a small counterclockwise swastika and what resembles the Tibetan letter A.

Dungma Dangsa

This site is situated near the base of Kunzam La, the pass linking Spiti with Lahul. There is a single boulder with rock art located here. The carvings consist of two ibex, a blue sheep and two other quadrupeds situated on the northeast side of the rock.

Fig. 23.1. The boulder with petroglyphs at Dungma Dangsa.

Fig. 23.2. The highly worn animal carvings at Dungma Dangsa.

Taktse

This petroglyphic site consists of just one boulder and is located at the base of Kunzam La. It was first documented in June, 2015 by members of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society. The carvings are reportedly comprised of 22 ibex. Additionally, there are Buddhist mantras and graffiti on the boulder. The ibex were made in a style comparable to carvings found in the lower part of Spiti.

Fig. 24.1. Ibex carvings at Taktse. The larger upper group of roughly carved petroglyphs date to either the Early Historic period (600–1000 CE) or Vestigial period (1000–1250 CE). The ibex on the lower left side of the boulder are probably of protohistoric antiquity. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Association.

Fig. 24.2. A close-up of some of the ibex carvings at Taktse. Note the Tibetan syllable Om in the upper middle portion of the photograph and the two Om near the bottom of the image. These inscriptions also date to the Early Historic or Vestigial period. Photo courtesy of the Spiti Rock Art and Historical Society.

Kubum

The pictographs of Kubum belong to one of four such sites in the upper half of Spiti. The rock art of Kubum is concentrated on the ceiling of a ledge in a cliff face. There are around thirty different subjects in total, consisting of swastikas, trees, sunburst and crescent moon, anthropomorphs (figures in human form), bird, and linear designs. Most of these figures were painted in a red ochre pigment of the same hue and agglutinative capacity. The pictographs have also worn in a similar manner (exhibiting comparable darkening and ablation characteristics).

The physical evidence indicates that rock art of Kubum was painted in the same general time. This art is attributable to the Protohistoric period. An Early Historic periodization, however, cannot be entirely discounted for certain pictographs, but at any rate, the pictographs of Kubum belong to the pre-Buddhist phase of cultural life in Spiti.

Among the various pictographs at Kubum are those with symbolic value (signs, tokens or emblems with ideological correlates) such as the swastika, tree, sun and moon. In fact, all the pictographs at Kubum may possibly have been painted with symbolic functions in mind. The peculiar selection of figures suggests that they articulate mythic, ritual and/or narrative themes. Thus they probably can be viewed as a cult production. A religious function is reinforced by the absence of hunting scenes and the paucity of animals more generally at the pictographic sites of Spiti. In contrast, hunting compositions dominate the petroglyphic art of Spiti. It can also be inferred from the contents that economic activities are not the paramount representation in the rock art of Kubum.

As discussed in the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, the subject matter of Kubum rock art also occurs in Ladakh and especially in Upper Tibet. This is indicative of trans-regional religious links stretching across the western portion of the Tibetan plateau in the Protohistoric period. Rock art figuration in a cult setting in this wider region can be equated with bon, a generic term for pre-Buddhist forms of Tibetan religion.*

Questions concerning the use of bon and Zhang Zhung in archaeological terminology pertinent to the “Western Tibetan Plateau” are explored in a forthcoming paper entitled, “Discerning Bon and Zhang Zhung on the Western Tibetan Plateau: Historical and cultural questions pertaining to archaeological nomenclature in the study of ancient rock art in Upper Tibet, Ladakh and Spiti”. It was written for the International Conference of Shang Shung Cultural Studies, Beijing, September 18–21, 2015.

The artistic repertoire of Kubum can be compared to the same kinds of symbols in the Tibetan textual tradition. However, it can not be proven that the rock art and the textual records are indeed in accord with one another. Correspondences in meaning are certainly indicated, but specific associations between Tibetan literature and rock art cannot be established with any surety. Typically, in the Tibetan literary tradition, the swastika, tree, sun and moon have cosmogonic, cosmological, apotropaic, and good-fortune connotations. Thus, in a general sense, we might expect the pictographs of Kubum to possess some or all of these broad categories of signification.

Kubum, like two other pictographic sites in Spiti, is hidden away at relatively high elevation. It is found at the head of a deep valley. The terrain is rugged and the site is not so easily reached. Its geographic position and the nature of the rock art suggests that Kubum was designed with restricted access in mind, consonant with the mystic or esoteric activities of a small or specialized group of people. We might conjecture, therefore, that a priestly corps or tribal/clan elite was responsible for the creation of the pictographs.*

The pictographs were not accessible and could not be measured. They range from around 7 cm to 18 cm in height.

Whatever the exact identity and function of the site, Kubum was of sufficient importance to be appropriated by Buddhist inhabitants after 1000 CE. It is evident from Buddhist constructions at the site that this religion was keen to incorporate it within its territorial and spiritual ambit. The name ‘Kubum’ itself (meaning “Thousand [Buddha] Images”) gives us some inkling as to its sacred status. The Sakya sect controlled the site for centuries and is still the caretaker. The Sakya sect founded their main monastery in Spiti called Tengyü (sTeng-rgyud) nearby, circa 13th century CE. It is not clear if the oldest Buddhist constructions at Kubum were established by the Sakya sect or if they devolved to it. The pre-Buddhist cult status of Kubum may have incited the Kadampa sect (active in Spiti from the late 10th century CE) to bring it under their auspices.

Fig. 25.1. The main concentration of red ochre rock paintings at Kubum. From left to right the main pictographs include swastika, unidentified, swastika, anthropomorph, sunburst, swastika, bird and anthropomorph, swastika, swastika and tree, swastika, anthropomorph or animal (?), swastika, swastika, crescent moon, linear design (tree?), swastika and tree, and tree, sun and moon.

A number of different people were responsible for the artwork of Kubum. What constitutes an integral composition among the various figures however is not always apparent. This is hardly important though because the entire rock face constitutes a unitary tradition of figuration and semantics. The ten or eleven swastikas were indiscriminately oriented in both directions. It was not until well into the Early Historic period that clockwise and counterclockwise swastikas assumed sectarian connotations. Some of the painted swastikas exhibit the primitive tendency of depicting the ends of the arms disproportionally small and sometimes out of sync with one another.*

For a discussion of the anthropomorph and bird and tree-sun-moon compositions, see the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, figs. 21, 80.

Fig. 25.2. A close-up of pictographs on the left end of the rock ceiling, Kubum. The anthropomorph appears to be depicted with a linear object in one hand and male genitalia (common in the rock art of Spiti). Note the primitive swastika below the sunburst.

Fig. 25.3. The middle portion of the rock ceiling. Note how the two ends of the vertical axis of the swastika in the middle left of the image are out of sync with one another.

Fig. 25.4. Tree and swastika on right side of ceiling.

Fig. 25.5. A view of the rim of the rock ceiling with a number of other pictographs, including swastikas and possibly anthropomorphs, Kubum.

Fig. 25.6. Three red ochre swastikas and cruciform painted on a cliff face near the rock ceiling, Kubum.

Thonsadrak

Thonsadrak is situated on the left side of the Spiti valley a few kms upstream of Kaza. The red ochre pictographs are found in three different locations on blue limestone cliffs rising above the river valley. Each of these locations consists of an overhang in the cliff above ledges that gave access to the rock faces used by painters.

Thonsadrak 1, the site furthest upstream, consists of a south-facing rock face suspended about 30 m above the Spiti valley floor. The pictographs here include swastikas (facing in both directions), three or four anthropomorphs, sunbursts, crescent moons and minor figures. Thonsadrak 2 is situated below Thonsadrak 1 and is comprised of three pictographs of somewhat ambiguous identity. Thonsadrak 3, a southwest facing cliff, is located further downstream. Pictographs here include a wild herbivore, counterclockwise swastika inside a square divided into two parts, series of vertical lines, a circle divided into two parts, and a few faint red ochre applications.

The subject matter represented at Thonsadrak is comparable with the other three main pictographic sites in Spiti, suggesting that its significance was mainly religious in nature. These pictographs can be dated to the Protohistoric period.*

I was not able to access most of the pictographs in order to measure them but they are of average size: approximately 7 cm to 18 cm in height.

Fig. 26.1. Members of the Spiti Antiquities Expedition (May-June, 2015) examining rock art at Thonsadrak 1.

Fig. 26.2. One of the rock faces at Thonsadrak 1. On the upper portion of the panel are two anthropomorphs flanking a swastika and crescent moon (partially effaced). Below the anthropomorph on the right is another swastika. On the lower part of the panel is a sunburst and horizontal line.

Fig. 26.3. A close-up of the upper portion of the panel pictured in fig. 26.2.

The upper four pictographs appear to form an integral composition. The anthropomorph on the left may be wielding a bow or some other instrument. This figure seems to be depicted with male genitalia. The anthropomorph on the right has one arm akimbo and is gesturing towards the two central elements in the composition, a crescent moon and a swastika. These two symbolic forms can be seen as cult objects, the focus of attention for the two anthropomorphs, who are oriented towards them as their arms convey. The crescent moon and swastika may possibly have been signs of lunar and solar deities, clan emblems, magical objects of ritual power, or have had alternative sacred functions. The lower right swastika may possibly have been painted as part of the composition. Be that as it may, it is a complementary addition to the rock panel.

Fig. 26.4. Close-up of sunburst and horizontal line on the lower part of the panel pictured in fig. 26.2.

Fig. 26.5. Pictographs on the rock face of Thonsadrak 2. From left to right: anthropomorph, sunburst, crescent moon, and sunburst. The darker red ochre sunburst on the right was made on a different occasion. Nevertheless, these respective compositions complement one another.

Fig. 26.6. Series of vertical lines and bisected circle, Thonsadrak 3.

Fig. 26.7. A wild herbivore (probably an ibex), Thonsadrak 3. There are nondescript pigment applications around this animal.

Nyima Loksa Phuk

Nyima Loksa Phuk is situated on steep rocky slopes high above the Spiti valley. This otherwise raw cave (2 m x 5 m) punctuates a limestone outcrop forming one side of a couloir. Red ochre pictographs are found on the sloping north wall of the cave. As noted in the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, Nyima Loksa Phuk translates as ‘Cave of the Reversal of the Sun’. According to local lore, this cave marks the return of longer days and an increase in the minimum elevation of the sun at the time of the winter solstice. The name suggests that astronomical readings were once made from this cave, probably as part of ritual observances. The sacred character of rock art in Nyima Loksa Phuk indicates that ritual use of the site can be traced back to the pre-Buddhist cultural milieu.

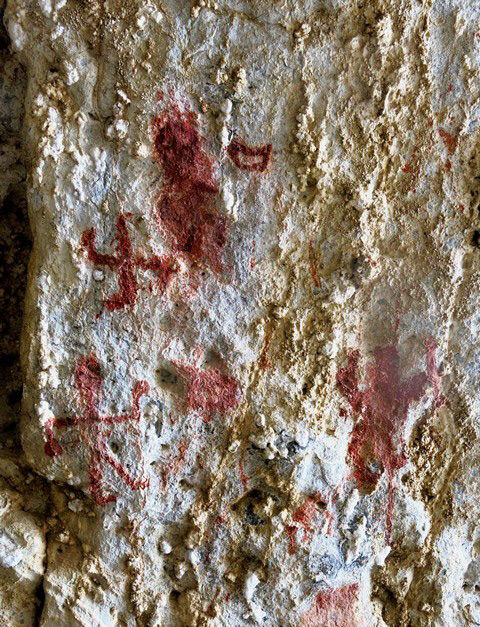

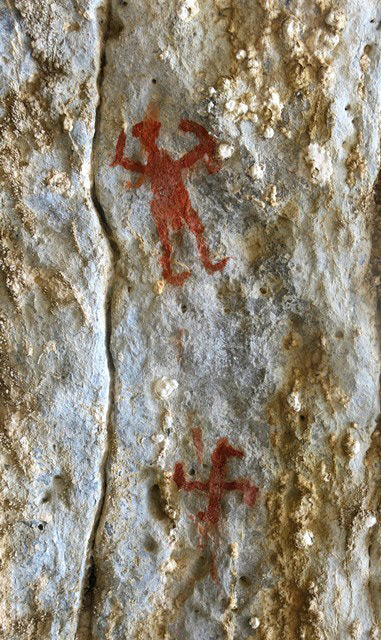

Like the other three main pictographic sites of Spiti, the pictographs at Nyima Loksa Phuk can be identified with the cult activities of a select group of people. In particular, the sun, moon, swastika and tree, four prominent subjects in the pictographs of Nyima Loksa Phuk, are closely connected to astronomical lore in the ancient ritual and cosmological literature of Tibet. The association of the cave with religious functions is also evident in its anthropomorphic art. Human figures in provocative aspects illustrative of a dance or some other type of ritualized movement are a conspicuous part of the site. These anthropomorphs gesture with their arms in close proximity to sacred symbols.

The pictographs of Nyima Loksa are attributable to the Protohistoric period. Although this array of red ochre paintings was created by different artists, thematically speaking, the various figures form a complementary whole. In the rock art of Upper Tibet portraying the same group of symbols, anthropomorphs are decidedly less numerous than in Spiti.

Fig. 27.1. The right half of the main panel at Nyima Loksa Phuk. Two anthropomorphs in matching poses reminiscent of a dance or some other kind of ritual behavior grace the upper portion of this part of the main panel. On the middle portion of the panel is an anthropomorph with outstretched arms and a swastika. On the lower portion (from right to left) is an anthropomorph with raised arms, tree and swastika.

Fig. 27.2. The left half of the main panel at Nyima Loksa Phuk. The upper portion consists of two swastikas, sun and crescent moon. On the lower portion of the panel are two anthropomorphs including one also seen in fig. 27.1.

Fig. 27.3. An adjacent part of the north wall of Nyima Loksa Phuk, with anthropomorph and swastika. These two pictographs may possibly have been painted at the same time.

Fig. 27.4. Upper right anthropomorphic figure (15 cm high) pictured in fig. 27.1. This figure has one arm akimbo and one arm flexed in some kind of demonstrative portrayal. It appears to be depicted with close-fitting headgear (perhaps a turban). Note the calcareous depositions that have formed over the ochre pigment, a process presumably centuries in the making.

Fig. 27.5. Upper left anthropomorph (16 cm high) in fig. 27.1. This figure matches the appearance of the anthropomorph in fig. 27.4 but it was probably made by another hand. These two figures face each other.

Fig. 27.6. The lower right anthropomorph (14 cm tall) in fig. 27.1. Arms outstretched, this figure may be depicted wearing a knee-length outer garment.

Fig. 27.7. Tree (15 cm high) on lower part of panel illustrated in fig. 27.1. This style of tree is typical of both Spiti and Upper Tibet.

Fig. 27.8. Close-up of the sun and moon pictured in fig. 27.2. The sun pictograph has been damaged by the smearing of the pigment. It appears to consist of a circle with a cross or swastika inside.

Fig. 27.9. Anthropomorphic figure (16 cm tall) on lower left half of panel pictured in fig. 27.2. While it was drawn in a different style from others already examined (stick arms and legs, round hands and teardrop-shaped head and upper torso), the arms of the figure are in a similar position to the specimens in figs. 27.4 and 27.5 and is also comparable to the aspect of two anthropomorphs at Thonsadrak 1.

Fig. 27.10. Close-up of anthropomorph (17 cm high) in fig. 27.3. This figure brandishes what looks like a shield and sword and appears to have male genitalia. Any depiction of weapons might be directly relatable to accounts in Tibetan literature of pre-Buddhist priests (bon and gshen) and their warlike activities. As already mentioned, much of the anthropomorphic rock art of Spiti is unambiguously marked as male.

Fig. 27.11. Swastika on panel illustrated in fig. 27.2.

Fig. 27.12. Another swastika in Nyima Loksa Phuk. Note how the ends of the vertical axis of the swastika are out of sync with one another. This is a common feature in the ancient rock art of the western part of the Tibetan plateau, which still persists today in some of the region’s folk-art.

Fig. 27.13. Another tree (19 cm tall) in Nyima Loksa Phuk.

Sinmo Khadang

A description of Sinmo Khadang (Gaping Mouth of the Cannibalistic Fiend) is found in the August 2015 Flight of the Khyung and I will not repeat it here. There are approximately 100 red ochre pictographs in this 80 m-long large cave, situated just below a summit dividing the main Spiti valley from the tributary valley of Kibbar (dKyil-bar).

The repertoire of rock art at Sinmo Khadang is comparable with the other pictographic sites of Spiti. In addition to trees, suns, moons, swastikas and anthropomorphs, there are two paintings of ibexes and a raptor pictograph in the cave. The pictographs of Sinmo Khadang were made by many different people. They primarily date to the Protohistoric period but some may possibly have been made subsequently in the Early Historic period. There is also a more recent red ochre pictograph consisting of a clockwise swastika with four dots painted inside its arms, as well as an obscured inscription in the uchen (dbu-can) script.

As explained in the August newsletter, there are calendrical cairns standing on the ridgeline above Sinmo Khadang that were used in premodern times to mark the passage of the seasons. As with celestial lore connected to Nyima Loksa Phuk, this may suggest that ritualized astronomical observances were once made from Sinmo Khadang. Unlike many large caves in Upper Tibet used for cult purposes, Sinmo Khadang does not appear to have had walls barricading its two mouths. This is one of a number of indications demonstrating that Spiti was not as well developed architecturally in early times as its large neighbor to the east (the ancient monuments of Spiti are explored in the December 2015 and January 2016 Flight of the Khyung).

Fig. 28.1. The south mouth of Sinmo Khadang overlooking the Spiti river valley.

Fig. 28.2. Members of the Spiti Antiquities Expedition exploring Sinmo Khadang.

Fig. 28.3. The largest concentration of pictographs at Sinmo Khadang. They are situated on the west wall of the cave near its south mouth.

Fig. 28.4. The lower right portion of the main concentration of pictographs, Sinmo Khadang.

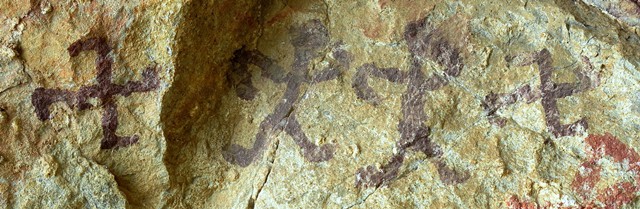

A raptor with diamond wings can be seen in the bottom center of the image (see August 2015 Flight of the Khyung, fig. 17). Above this raptor in ascending order is a pair of anthropomorphs, swastika, unidentified subject to left of swastika, swastika (far right), circle and more angular geometric forms, tree and swastika, swastika and crescent moon, and bell-like form.

Fig. 28.5. Pair of anthropomorphs (around 9 cm high), arms and legs spread, pictured in fig. 28.4. These two figures constitute an integral composition.

Fig. 28.6. Close-up of circle and other geometric forms in fig. 28.4. These figures appear to form a single composition. The identity of these pictographs is unclear.

Fig. 28.7. Close-up of tree (17 cm high) in fig. 28.4. To its left is a swastika (only partially visible in the image).

Fig. 28.8. Swastika, crescent moon (15 cm long) and campanulate form illustrated in fig. 28.4. The swastika and crescent form one composition. The dark red bell-like subject was painted separately.

Fig. 28.9. A composition consisting of a pair of anthropomorphic figures (around 9 cm high) located in middle of the cave wall pictured in fig. 28.3. Their arms and legs swing wide, suggesting that these figures are dancing or engaged in some other kind of coordinated behavior suggestive of ritualism.

Fig. 28.10. Pictographs on west wall of Sinmo Khadang situated above rock face in fig. 28.3. There is a large sunburst in the middle of the image. Above it is a pair of anthropomorphs flanked by swastikas forming a single composition.

Fig. 28.11. Close-up of sunburst in fig. 28.10. This sun has nine points and some internal elements. The numerical arrangement of the sunrays is not liable to be a coincidence. The number nine played a prominent role in the archaic religious traditions of Tibet, as a survey of Tibetan literature confirms. In Tibet the number nine still carries connotations of a ‘multitude’, ‘completeness’ and ‘universality’.

Fig. 28.12. Another pair of anthropomorphs in an aspect very similar to that assumed by human figures in Thonsadrak and Nyima Loksa Phuk (see figs. 26.2, 27.4 and 27.5).

The swastikas clearly play an important part in this integral composition, lending it a cult context. In the vein of speculation: perhaps these swastikas represent the presence or benefaction of clan or tutelary deities. The red ochre pigment used to paint the composition has an unusually dark hue. It is the only example of this type of pigment found in the rock art of Spiti.

We can infer from the anthropomorphic rock art of Sinmo Khadang, Nyima Loksa Phuk and Thonsadrak that figures with one arm curled up and one arm bent down constituted a conventionalized gesture or motion. What this might have signified is matter of speculation. What can be stated is that the placement of the arms and the spreading of the legs in these and in other anthropomorphic pictographs of Spiti convey a highly expressive and dynamic theme.

Arms extended out or raised overhead in this rock art is at variance with many of the anthropomorphic petroglyphs in Spiti. The carved figures (some of which are considerably older) are frequently depicted with their arms in a downward position. Arms and hands oriented towards the ground seem to allude to chthonic imagery and symbolism. On the other hand, the pictographic figures of Sinmo Khadang, Nyima Loksa Phuk and Thonsadrak hint at a celestial perspective or background, which is enhanced by the lofty setting of the three sites. The socioeconomic backdrop of the pictographs and petroglyphs is also at variance. The petroglyphic figures are directly or indirectly associated with the hunting of wild caprids (primarily blue sheep and ibex), while venatic themes are virtually absent in the pictographs.

Fig. 28.13. Tree (13 cm high), sun and swastika on west wall of Sinmo Khadang. This integral composition has strong symbolic overtones.

Fig. 28.14. Tree (20 cm high) and swastika on east wall of Sinmo Khadang.

Fig. 28.15. Counterclockwise swastika on east wall of Srinmo Khadang.

Fig. 28.16. Sunburst (14 cm long) on west wall of Sinmo Khadang.

Fig. 28.17. Ibex (8 cm long) in close proximity to sun pictured in fig. 28.16.

Fig. 28.18. Ibex painted on west wall of Sinmo Khadang.

Fig. 28.19. Crescent moon and swastika situated near the north mouth of Sinmo Khadang. There is also a red ochre tree pictograph in the vicinity.

Fig. 28.20. Swastika with dots between the arms. This is a much more recent pictograph, undoubtedly inspired by the earlier rock art of Sinmo Khadang. Below the swastika are a few Tibetan letters of considerable age.

Ahead into the Historical Era: Non-Tibetan rock inscriptions in Spiti

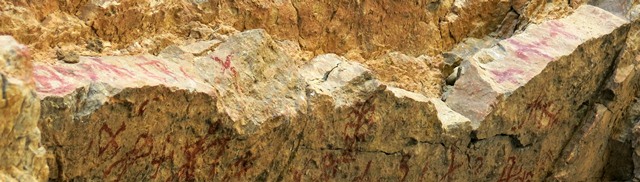

This brief article presents three sets of carvings that may possibly be inscriptions. All three sets of engravings are found among the rock art of the lower portion of Spiti (sPi-ti gsham). They exhibit a significant degree of wear and re-patination consonant with considerable age.

The three sets of engravings are not readily identifiable due to their brevity (two to four units each) and the unusual formation of each of the ‘characters’. It is possible that these engravings were derived from or inspired by the proto-Sarada alphabet of the 10th–12th centuries CE, but this remains to be confirmed. It is also possible that they are the handiwork of individuals merely imitating scripts used in the wider region, creating pseudo-inscriptions. Alternatively, the engravings may be alphabetical abbreviations of some kind. These last two possibilities are rendered more likely by the very short length of each set of engravings. Alternatively, these carvings may be symbols or ciphers or have ideographic value.

Fig. 1. These carvings are found on top of a boulder in close proximity to two nondescript petroglyphs created in the same time frame.

Fig. 2. The two carvings were made on a boulder with older zoomorphic petroglyphs. This boulder is located in the uppermost part of District Kinnaur, across the Spiti river from lower Spiti.

Fig.3. These two carvings are found on the opposite side of the boulder pictured in fig. 2.

Next Month: Up and away to the ancient strongholds of Spiti!