March 2016

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to Flight of the Khyung as we take in the most ancient bronzes of Tibet! This month’s newsletter presents the second part of an article on the art history and archaeometallurgy of pre-Buddhist copper alloy objects from the Western Tibetan Plateau and adjoining regions. Part 2 is primarily focused on cross-cultural contacts between the Tibetan Plateau and other regions of Inner Asia in the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

For the first part of the article, see last month’s newsletter: “A Preliminary Study of the Origins and Early Development of Bronze Metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Part 1: The ‘Eurasian animal style’, an art historical perspective”. It is advised that readers begin with Part 1 of the article in order to acquaint themselves with the material.

A Preliminary Study of the Origins and Early Development of Bronze Metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau

Part 2: Intercultural contacts in the Bronze Age and Iron Age, an archaeometallurgical perspective

Abstract

An analysis of a broad range of art historical and archaeological evidence indicates that the pre-Buddhist corpus of Tibetan bronze objects known as thokchas originated from a cross-fertilization of technological and ideological elements of the Northern Metallurgical Province of the Late Bronze Age and Scythic cultures of the Iron Age with the creative capabilities of autochthonous Tibetan cultures.

Introduction

This part of the article explores the origins and development of bronze metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau (WTP). Most of the comments and insights offered below are predicated on an assessment of the styles and designs of small Tibetan bronze objects known as thokchas, and examining these artifacts in light of archaeological findings from Inner Asia.

The extent of copper and bronze metallurgy on the WTP in the Bronze Age is still obscure. Nonetheless, as we saw last month in the first part of this article, affinities between bronze metallurgy on the WTP and neighboring regions during the Iron Age have been documented through a variety of metallic objects available for study. It was in the Iron Age that production of copper alloy talismans and other types of metallic objects increased substantially in Tibet, part and parcel of new forms of development in the technological, architectural and social spheres.

The origins of metallurgy on the WTP are shrouded in mystery. The same can be said for Central Tibet (dBus-gtsang, Lho-kha and rKong-po) as well. Only a relatively small number of ancient copper, bronze, silver, gold items have been discovered by archaeologists in these regions and very few objects have been dated in a scientifically sound matter. Moreover, little attempt has been made by Chinese archaeologists to integrate artifacts recovered into a comprehensive typological and analytical framework.* The loss of an incalculable number of ancient copper and bronze artifacts to the arts and antiquities market over the last forty years further complicates the picture.

A preliminary survey of ancient metal artifacts in Tibet was recently written by Huo Wei, an archaeologist at Sichuan University. His work is a helpful review of some findings made by Chinese archaeologists in Tibet since the 1980s. Huo Wei integrates information presented in Chinese and foreign publications (some of these sources are cited in his article, others are not). See Huo Wei. 2014: “Shi lun Xizang faxian de zaoqi jinshuqi he zaoqi jinshu shidai (On the Early Metal Wares and Early Metal Age in Tibet)”, in Kaogu Xuebao, no. 3, pp. 327–350. Beijing: Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

This study utilizes thokchas from private collections around the world. As part of my ongoing efforts to understand the cultural and historical complexion of pre-Buddhist Tibet, I have tried to gain access to as many private collections of Tibetan bronze artifacts as possible. Over the last three decades, I have also made extensive observations in the Chinese and international arts and antiquities market, significantly expanding the range of objects available for study. Since 1986, these methods have permitted me to view no less than 10,000 thokchas (around 2300 of which appear in various publications).

Having recourse to a large body of data is essential in understanding the ancient tradition of Tibetan metallurgy. However, I was only able to obtain photographs of a small fraction of all the thokchas observed. Those who sell such wares are not often amenable to having their stock photographed for what they might see as dubious purposes. Although I have viewed many thokchas, countless more have escaped my eye. There are a number of collections known to me worldwide that have not been published and there are surely other collections as well. In the last few years, the dispersal of thokchas to those wanting Tibetan religious symbols or good luck pieces in China, Taiwan and other countries has further muddied the waters for any encompassing appraisal of the subject.

Archaeometallurgy (archaeological study of ancient metals) is based upon scientific methods, including the retrieval of materials in secure contexts and their study using an array of modern tools. These methods permit a picture to emerge of the production and use of metals in particular cultural, chronological and geographic settings. Central to archaeometallurgy is ascertaining what relationships ancient metals have to other archaeological materials and processes, in order to determine their roles in the cultural, economic, political, and religious lives of ancient peoples. Unfortunately, the uncontrolled procurement of bronze artifacts from art and antiquities markets strips them of much scientific significance, obscuring spatial and temporal values essential to quantifiable, verifiable and reproducible forms of analyses.

The spread of bronze metallurgy to Xinjiang, northwest China and far eastern Tibet

Before we return to an examination of Tibetan bronze objects, let us review the broader region through an archaeometallurgical perspective. Except for some parts of southeastern Tibet (in northwestern Yunnan and western Sichuan), it has not been determined when metallurgy or imported metal objects first came to Tibet. It has been confirmed though that far eastern Tibet was heavily influenced by northern metallurgical traditions.

Recent evidence indicates that bronze metallurgy was introduced to southeastern Tibet through northwestern China (Gansu and Qinghai) in the Bronze Age (these regions were outside the Han cultural and ethnic sphere in that period).* It was previously thought that bronze metallurgy in southeastern Tibet dated to circa 800–500 BCE, but recent Sino-Japanese excavations have pushed back its origins to the 15th to 12th centuries BCE (ibid., 87). Bronze halberds from the site of Yan’erlong dated to second half of the second millennium BCE and other halberds discovered in the general region have affinities to Bronze Age cultures of the steppes (Karasuk and Andronovo),† which provided the historical inspiration behind production of these weapons (ibid., 82).

See Miyamoto, Kazuo. 2014: “The Emergence and Chronology of Early Bronzes on the Eastern Rim of the Tibetan Plateau”, in The Crescent-Shaped Cultural-Communication Belt: Tong Enzheng’s Model in Retrospect: An examination of the methodological, theoretical and material concerns of long-distance interactions in East Asia (ed. A Hein), pp. 79–88. BAR International Series 2679. Oxford: Archaeopress. This study came out of a Sino-Japanese archaeological project that carried out excavations of tombs at the Yan’erlong site (ca. 1670–1050 BCE), in the upper Yalong river valley, Yunnan, in 2008–2010 (pp. 80. 82). Findings from southeastern Tibet suggest that bronze production in southwest and northeast China developed separately, casting doubt on Tong Enzheng’s crescent-shaped diffusion model. Rather, eastern Tibet was directly linked to the “Northern Zone” (ditto, northwestern China; ibid., p. 87).

Note that in this and other articles cited reference is made to a number of different archaeological cultures. An archaeological culture is determined through analogous bodies of artifacts, architecture and burials within defined geographic and chronological limits. An archaeological culture does not necessarily correspond to how a prehistoric people defined their own cultural status, thus it may say little or nothing about language, tradition, ethnicity or identity. Although of practical utility in scientific study, it is increasingly recognized that the concept of an archaeological culture has inherent limitations. This is essentially because it applies a static set of criteria to a definition of culture, a dynamic and largely intangible shaper of human behavior.

A handled mirror found at the Galazong burial site (1390–530 BCE) in northwestern Yunnan indicates that Gansu-Qinghai influenced the production of metal objects in southeastern Tibet, as part of the same northern bronze metallurgical tradition (ibid., 81, 82). Based on double-handled ceramics, metal weapons and cist tombs in northwestern Yunnan and western Sichuan, it can be shown that complex influences and transfers were involved in this process, not just a single wave of diffusion.* However, the nature of cultural interrelationships between these conterminous regions remains unclear (ibid., 4, 5). In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, there was another phase of interaction between southeastern Tibet and the Northern Zone, marked by bronze belt plaques, iron daggers with bronze handles, and the remains of animal sacrifice (Miyamoto 2014: 87). Many of these objects feature art in the Eurasian animal style.

See Hein, Anke. 2014: “Introduction: Diffusionism, Migration and the Archaeology of the Chinese Border Regions”, in The Crescent-Shaped Cultural-Communication Belt: Tong Enzheng’s Model in Retrospect: An examination of the methodological, theoretical and material concerns of long-distance interactions in East Asia (ed. A Hein), pp. 1–17. BAR International Series 2679. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Small amounts of copper and bronze objects (mostly rings and fc vbnm,/ were discovered in northeastern Tibet, in Bagou, Tongde County (’Ba’-rdzong), Qinghai (Amdo), in the mid-1990s.* Believed to date to the Bronze Age, these artifacts have been categorized in an archaeological culture styled Late Zongri (ibid.). This culture is thought to have had associations with the Qijia and Majiayao cultures of lower elevation regions of Qinghai (ibid.). Unfortunately, to date, very little has been published on the so-called Late Zongri culture.

See p. 38 of Jianjun Mei / Xu Jianwei / Chen Kunlong / Shen Lu / Wang Hui. 2012: “Recent Research on Early Bronze Metallurgy in Northwest China”, in Scientific Research on Ancient Asian Metallurgy. Proceedings of the Fifth Forbes Symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art, pp. 37–46. Washington, D.C.: Archetype Publications with the Freer Gallery of Art.

Archaeological evidence strongly suggests that bronze metallurgy in the Eurasian steppes preceded its development in northwestern China, which predates its emergence in southwestern China.* The Eurasian steppes and northwestern China also had some impact on the appearance of bronze metallurgy in the central plains of China and in southeast Asia. It is not clear however how bronze metallurgy was carried from the steppes to northwestern China, or what role independent innovation might have played in the process. It is generally thought that there were probably two major bands of diffusion: one coming from the mountains and deserts to the west and another one issuing from Mongolia in the north. The characteristics of metal objects (composition, metallurgical technologies and object types) in northwestern China in the early second millennium BCE is related to southern Siberia, suggesting the movement of newcomers into the Hexi (Gansu) corridor who may have been horse riders of Andronovo cultural affiliation.†

For an understanding of the key role played by the Eurasian steppes in the dissemination of bronze metallurgy to Xinjiang and northwestern China, see:

Bunker, E. C. 1998: “Cultural diversity in the Tarim Basin vicinity and its impact on ancient Chinese culture”, in The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age peoples of eastern Central Asia (ed. V. H. Mair), pp. 604–618. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania Museum Publications.

Debaine-Francfort, Corinne. 2001: “Xinjiang and northwestern China around 1000 bc: Cultural contacts and transmissions”, in Migration und Kulturtransfer: Der Wandel vorder-und zentralasiatischer Kulturen im Umbruch vom 2. zum 1. vorchrislichen Jahrtausend (eds. R. Eichmann and H. Parzinger), pp. 57–70. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

Debaine-Francfort, Corinne. 1995: Du néolithique à l’âge du bronze en Chine du nord-ouest: La culture de Qijia et ses connexions. Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations.

Kuzmina, E. E. 1998: “Cultural connections of the Tarim Basin people and the pastoralists of the Asian steppe in the Bronze Age”, in The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age peoples of eastern Central Asia, (ed. V. H. Mair), pp. 63-93., Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania Museum Publications.

See Linduff, Katheryn M. and Jianjun Mei. 2015. “Metallurgy in Ancient Eastern Asia: Retrospect and Prospects”, in Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Synthesis (eds. B. W. Roberts and C. Thornton), pp. 785–803. New York: Springer.

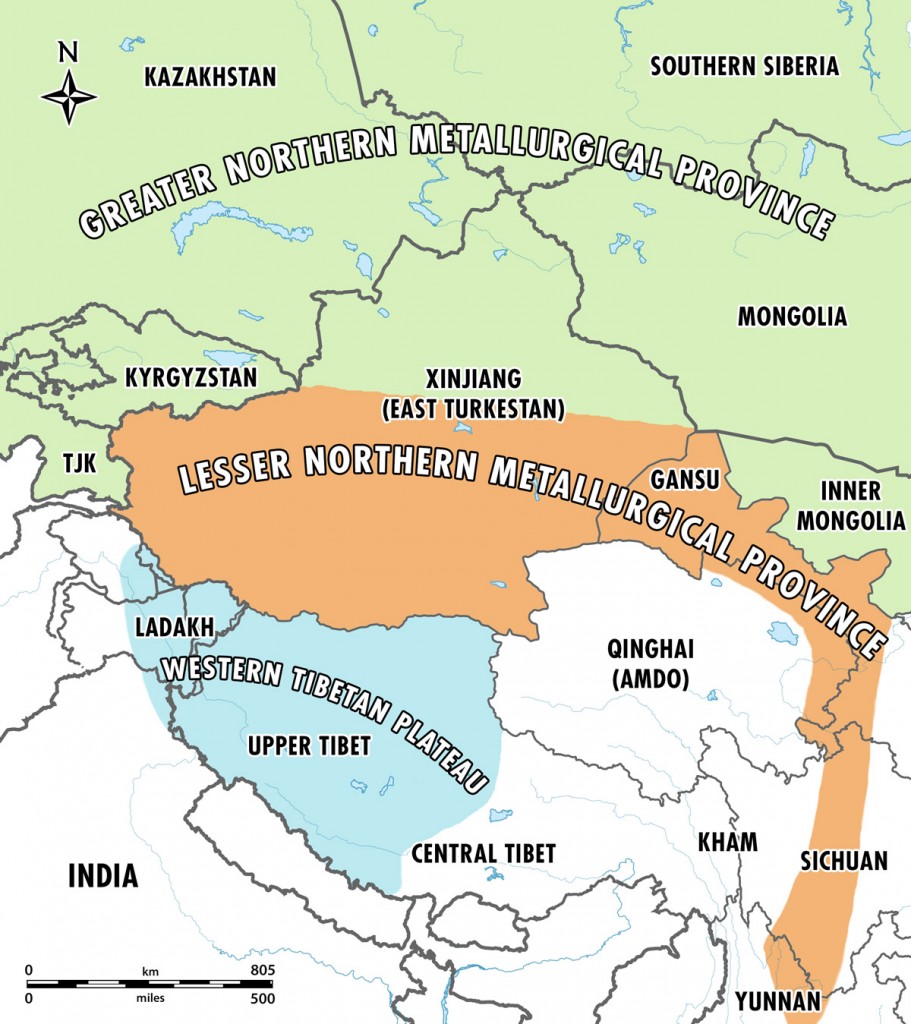

Map of Inner Asian metallurgical relations in the Late Bronze Age. Note that only some modern names of countries shown are designated. Modern international and internal boundaries delineated are approximations only. Map by Brian Sebastian and John Vincent Bellezza.

It is increasingly accepted that cognate forms and technologies in the various assemblages of bronze objects make it permissible to speak of a “Northern Bronze Complex” or “East Asian Metallurgical Province” comprised of the Sayan-Altai, Mongolia and Gobi, which according to E. N. Chernykh, represents the rapid expansion eastward of Karasuk culture metallic forms, circa 1400–1000 BCE.* Given the multifarious affinities in bronze metallurgy, this zone of allied traditions can be expanded to include Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet. For the purposes of this article, this augmented territory will be referred to as the “Greater Northern Metallurgical Province” (GNMP). As a subsidiary part of this metallurgical realm, southern Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet will be labeled the “Lesser Northern Metallurgical Province” (LNMP).

See pp. 139–141 of Chernykh, Evengii, N. 2009: “Formation of the Eurasian Steppe Belt Cultures: Viewed Through the Lens of Archaeometallurgy and Radiocarbon Dating”, in Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility (eds. B. K. Hanks and K. M. Linduff), pp. 115–145. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. On the Eurasian steppe tradition of bronze metallurgy and its spread to northwestern China, also see Jianjun Mei et al. 2012, p. 36.

There is considerable evidence in Inner Mongolia after 1500 BCE for objects of the Northern Bronze Complex, which closely resembles bronze artifacts of the Karasuk culture (ca. 1500 BCE to first millennium BCE) in southern Siberia and objects of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon (ca. 1900–1500 BCE). See p. 17 of Shellac-Lavi, Gideon. 2015: “Steppe Land Interactions and Their Effects on Chinese Cultures during the Second and Early First Millennia BCE”, in Nomads as Agents of Cultural Change: The Mongols and their Eurasian Predessecors (eds. R. Amitai and M. Biran), pp. 10–31. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

The Seima-Turbino phenomenon denotes the relatively rapid and widespread dispersal of tin-bronze objects (socketed spearheads and axes and knife-daggers) across the Eurasian steppes. It appears to have originated in the Altai and central Mongolia with their abundant tin deposits and spread to the east and to the west.

Recent studies have confirmed the crucial role the Gansu-Qinghai region played in the development of copper and bronze metallurgy in northwest China during the first half of the second millennium BC.* Most of the early copper and bronze objects discovered in the Gansu-Qinghai region are associated with the so-called Qijia (upper Yellow River valley [rMa-chu]), ca. 2200–1600 BCE) and Siba (Hexi corridor, ca. 1600–1000 BCE) cultures (ibid.). Metallurgical analyses demonstrate that cupreous objects of the Qijia and Siba cultures are made from arsenical bronze, tin-bronze and pure copper and are largely of indigenous production (ibid.). These cultures produced copper and bronze knives, mirrors, axes, awls, earrings, and spearheads, etc.

See discussions in Jianjun Mei / Pu Wang / Kunlong Chen / Lu Wang / Yingchen Wang / Yaxiong Liu. 2015: Archaeometallurgical studies in China: Some recent developments and challenging issues”, in Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 56, pp. 221–232. Elsevier.

It is thought that the Qijia and Siba were probably most closely connected to cultures in the west. Be that as it may, these two archaeological cultures extend from the northeast corner of the Tibetan Plateau to the Hexi corridor, making it unlikely that they were monolithic cultural groups in the anthropological sense of the word. At the very least, the great environmental contrasts between lowland and highland sites would have required dissimilar adaptation strategies. It is more plausible that the interrelated material repertoire of the particularly diverse Qijia territory is the product of two or more ancient cultures in contact with one another.

It has been established that Bronze Age Xinjiang (East Turkestan) lay on a path of interactions extending from the steppe to Qinghai-Gansu.* Painted pottery spread westward from Gansu into Xinjiang and bronze technology spread westward from the Eurasian steppe to Xinjiang, indicating two-way cultural transmissions.† It is now generally accepted that metallurgical contacts between southern Xinjiang and southern Siberia can be traced to the beginning of the second millennium BCE or somewhat earlier.

There was probably a wide range of metallurgical exchanges between southern Siberia, Gansu and Xinjiang in the late third to early second millennium BCE. Qijia bronze objects show strong affinities with the Seima-Turbino phenomenon, which reached northwestern China either from Xinjiang but more probably from the Mongolian Altai. See pp. 837, 838 of White, Joyce, C. and Hamilton, Elizabeth, G. 2015: “The Transmission of Early Bronze Technology to Thailand: New Perspectives”, in Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective: Methods and Syntheses (eds. Benjamin W. Roberts, Christopher Thornton), pp. 805–851. New York: Springer.

See pp. 216, 217 of Jianjun Mei. 2009: “Early Metallurgy and Socio-Cultural Complexity: Archaeological Discoveries in Northwest China”, in Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility (eds. B. K. Hanks and K. M. Linduff), pp. 215–232. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The earliest Bronze Age remains (including metals) in Xinjiang are quite limited, suggesting that the region was sparsely populated before the arrival of Europoids from the west prior to 1800 BCE.* This early population is commonly equated with the Tocharians.† It is also thought that herders from the Altai migrated to the Tarim Basin at a somewhat earlier date, forming the Shamirshak (Uighur) / Qiemu’qiereke (Chinese) culture.‡ It exhibits traits of archaeological cultures from the western and eastern steppes including the Afanasievo, Okunev and Catacomb-Poltavka cultures (ibid., 67).

See pp. 92, 93 of Kohl, Philip, L. 2014: “Concluding Comments: Reconfiguring the Silk Road or When Does the Silk Road Emerge and How Does it Qualitatively Change Over Time?”, in Reconfiguring the Silk Road: New Research on East-West Exchange in Antiquity (eds. V. H. Mair and J. Hickman), pp. 89–94. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

On the Tocharians in Xinjiang, see Mallory, J. P. 2015: The Problem of Tocharian Origins. Sino-Platonic Papers, vol. 259. Philadelphia: Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp259_tocharian_origins.pdf

See p. 66 of Anthony, David, W. and Brown, Dorcas, R. 2014: “Horseback Riding and Bronze Age Pastoralism in the Eurasian Steppes”, in Reconfiguring the Silk Road: New Research on East-West Exchange in Antiquity (eds. V. H. Mair and J. Hickman), pp. 55–72. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

One of the most important earlier Bronze Age (first half of second millennium BCE) sites in Xinjiang is the cemetery at Xiaohe, situated on the eastern edge of the Tarim Basin. Wheat (a crop introduced from the west) and millet (a crop introduced from the east) were being cultivated in Xiaohe, circa 2000 BCE.* No metal implements were found at Xiaohe (only small strips of tin-bronze and leaded bronze and gold earrings), but cut marks on coffins and ceremonial poles suggest metal tools were used to make them (Jianjun Mei 2009: 224; Jianjun Mei et al. 2012: 37, 40). Electrum earrings from Xiaohe are believed to have been imported, as there are no known gold deposits in the Tarim Basin (Jianjun Mei et al. 2012: 40).

See p. xi of Renfrew, Colin. 2014: “Foreword: The Silk Roads before Silk”, in Reconfiguring the Silk Road: New Research on East-West Exchange in Antiquity (eds. V. H. Mair and J. Hickman), pp. xi–xvi. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Typological analysis of socketed spearheads and axes, mirrors, and awls and knives with bone handles of the Qijia and Siba cultures and the Tianshanbeilu culture (eastern Xinjiang, ca. 2000–1550 BCE) shows that these types of objects have cognate forms, as part of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon and as part of the Andronovo culture (ca. 2000–1400 BCE) and Okunev culture (ca. 2200–1800 BCE) of the eastern steppes (Jianjun Mei 2009: 217).* Nevertheless, many typical metal objects of the steppes such as socketed celts with geometric patterns and daggers and knives with zoomorphic handle decorations (Seima-Turbino phenomenon) and shaft-hole axes (Andronovo) are not represented among the metal objects of the Qijia, Siba and Tianshanbeilu cultures,† which according to Jianjun Mei, suggest that communications between these cultures were indirect, small-scale and sporadic and not involving large demic transfers (2009: 218). To support his view, Jianjun notes that certain designs and styles in the bronze cultures of northwestern China are indicative of local technological and esthetic innovation (ibid. 219).‡

There is substantial evidence for bronze metallurgy in various parts of Xinjiang exhibiting Andronovo influences. These influences are particularly strong in northwestern Xinjiang, but also extend to Gumugou situated in Lop Nor (probably of same archaeological culture and time period as Xiaohe) along the east side of Tarim Basin, and Aketala near Kashgar. Thus far evidence for Andronovo contacts does not seem to extend to the southern rim of the Tarim Basin. In addition to mostly stray finds of copper and bronze artifacts, Andronovo cultural affinities in Xinjiang are present in funerary structures, animal sacrifice rituals and ceramic vessels (in form and in decorative treatment comprised of incised diagonal lines). See Jianjun Mei and Shell Colin. 1999: “The existence of Andronovo cultural influence in Xinjiang during the 2nd Millennium BC”, in Antiquity, vol. 73, pp. 570–578. Durham: Department of Archaeology, Durham University.

The Tianshanbeilu culture appears to have been an intermediary link between the Hexi Corridor and the Eurasian steppe, thus eastern Xinjiang was crucial in tying together the Bronze Age cultures of the wider region. This is indicated by a typological and technological analysis of bronze objects. See pp. pp. 17–21 of Jianjun Mei. 2003a: “Cultural Interaction between China and Central Asia in the Bronze Age”, in Proceedings of the British Academy, vol. 121, pp. 1–39. Oxford: The British Academy, Oxford University Press. The Tianshanbeilu copper and bronze assemblage represents the oldest occurrence of metals discovered to date in Xinjiang (Jianjun Mei et al. 2012: 40).

Use of arsenical copper in northwest China in the second millennium BCE and in Xinjiang in the second and first millennia BCE is presaged by the central and western parts of the Eurasian steppes during the late third and early second millennia BCE. The transmission of this alloy east would have encompassed many intermediaries, suggesting that arsenical copper was locally produced in Xinjiang as part of a chain of transference. See pp. 43, 44 of Jianjun Mei. 2003b: “Qijia and Seima-Turbino: The Question of Early Contacts Between Northwest China and the Eurasian Steppe”, in The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (Östasiatiska Museet). Stockholm. Bulletin No. 75, pp. 31–54. Stockholm: The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. The tin-bronze repertoires of the Tianshanbeilu, Qijia and Siba cultures are comparable to that of the Okunev culture of the steppes, which in turn has strong similarities to the Seima-Turbino complex (ibid., 40, 41). Earrings with trumpet-shaped ends, sickles, flat axes, awls and open-socketed axes also suggest eastward penetration of Andronovo cultural influences (ibid., 41). However, plain mirrors are found at Tianshanbeilu, Qijia and Siba sites but not at Seima-Turbino or Okunev sites, and only a few plain mirrors have been discovered at Andronovo sites, suggesting that these mirrors were actually made in Xinjiang and northwestern China (ibid., 42).

Recent research conducted on a small sample of metal objects discovered at the Xiaohe cemetery furnish more evidence for the use of tin-bronze in Xinjiang during the early and middle second millennium BCE. See Jianjun Mei et al. 2015: 222.

Cultural processes involved in the adoption of bronze metallurgy in Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet

Prospects for the truly independent invention of bronze metallurgy in any one culture of the eastern steppes and LNMP (southern Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet) in the Late Bronze Age appear to be rather limited. That a single people in this region in complete isolation developed all of the technologies required on their own is discounted in current scholarly thinking. In any event, the discussion to follow is focused on interregional processes and how these may have facilitated the adoption of bronze metallurgy in the LNMP.

It is widely considered that a generally colder and drier climate in eastern Eurasia in the Late Bronze Age may have set in motion migrations and other social and cultural changes associated with the development of bronze metallurgy in the region.

The broad array of ethnicities, cultures and languages involved in the dissemination of bronze metallurgy is known to us in proxy through the archaeological cultures of Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet. The diffusion of copper alloy objects and technologies in these regions in the Late Bronze Age, however, was not simply predicated on a two-way avenue linking a handful of archaeological cultures. Vectors of transference are better seen as multifaceted, encompassing a wide cross-section of languages, ethnicities and cultures.

The expansive territory of the LNMP was home to an unknown number of distinctive peoples, each with their own sets of customs, traditions, social structures, identities, political systems, economic patterns, etc.; all those things constituting the highly complex human phenomenon called ‘culture’. I take as my departure point the assumption that an inclusive set of human behaviors, activities and beliefs, directly or indirectly, is embodied in archaeological materials and processes. Simply put, archaeological phenomena are imprinted with culture expressed through society. Utilizing an anthropological model to characterize the cultural complexion of the 2500-km long swathe of territory between northern Xinjiang and southeastern Tibet paves the way to a nuanced theoretical discussion regarding the spread of bronze metallurgy there.

In my view, the diffusion of bronze metallurgy in the LNMP was dependent on a web of sociocultural forces and the multi-articulated communications they spawned in the region. A conjunction of different peoples served to project technological innovation farther and farther afield, effectively as part of the Zeitgeist or interregional consciousness of the times. It appears to me that the transfer of bronze objects and metallurgy was not a sporadic occurrence but a sustained progression (rapid or otherwise) engulfing one people after another in Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet. This technological contagion is likely to have expedited a wide range of interactions (symbiotic and conflictive) between societies in the Late Bronze Age, both pastoral and agrarian.*

For a profitable discussion on technological and ideological contagion in the global context of Bronze Age Eurasia, see Anthony, David, W. 2010: The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

For a model of Bronze Age social interaction in the eastern Eurasian steppes predicated on pastoralist strategies redefining local landscapes and promoting wider networks of exchange, which seem to have led on occasion to flashes of rapid connectivity and diffusion, see Frachetti, Michael D. 2008: Pastoralist Landscapes and Social Interaction in Bronze Age Eurasia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

The spread of bronze metallurgy was but one mechanism in interactions between peoples over a wide geographical compass. Other crucial mechanisms advancing long-distance communications in the Late Bronze Age included the spread of cultivars, stock-rearing, ceramics production, and mobile economies.

The actual transfers of bronze metallurgy in the LNMP entailed either the short or long distance movement of craftsmen and technologists. Migration of workers could have taken place under any manner of compulsions or incentives, the vanguard of a process with significant sociocultural ramifications.

While the general movement of bronze metallurgy appears to have been from west to east and north to south, other patterns of propagation may have been in operation as well. Very isolated areas or particularly conservative cultures could have adopted metallurgy later than peoples to their east or south. Conversely, more progressive cultures may have developed it earlier than their neighbors.*

Postulating alinear vectors of transmission may help to explain the dating of bronze objects that do not match the geographic trends. For example, there is evidence for possible local bronze production in the Hexi Corridor in the late third millennium BCE (Jianjun Mei 2015 et al.: 222), and a few copper and bronze objects found at Majiayao and Machang sites in Gansu are thought to date to the early and late third millennium BCE respectively (Jianjun Mei 2009: 220, 222). This evidence for metallurgy in northwestern China is earlier than would be expected if solely east-west and north-south directional impulses were in operation.

I believe that the pervasive dispersal of metallurgy in the LNMP was fostered by the intrinsic qualities of metal objects. These qualities can be summarized as follows: utility (objects have a wide range of practical applications), mobility (they are easily transported), fungibility (they are readily exchanged), and prestige (they are status enhancing).

I maintain that the adoption of bronze metallurgy was essentially an endogenous process, leading to its naturalization among each people that lay along the web of diffusion. This indigenization was of course informed by interregional cultural, political and economic currents. As bronze metallurgy spread, its technologies and forms were recreated and reinterpreted by each adopting polity and culture, accounting for the localized assemblages of bronze objects produced in Xinjiang, Qinghai and Gansu, etc. An organic or multicentric system of transfers does not preclude the intrusion or import of foreign bronze technologies and objects over long distances, but its main effect was to spur on metallurgical developments of a largely indigenous persuasion. I think it is along these lines that a synthesis of diffusionist and localizationist models may be attempted.

I concur with Jianjun Mei (supra) that one does not necessarily need to postulate the mass movement of people to account for the widespread dispersal of Seima-Turbino, Okunev, Andronovo or Karasuk bronze objects and influences in the LNMP. However, I do see interregional contacts as being extremely consequential to overall technological and cultural development in the Late Bronze Age. The acquisition of metallurgical capabilities and materials emanating from the Eurasian steppe and their reconfiguration in sundry cultures of Xinjiang and northwestern China, etc. must have helped to enhance strategic goals and consolidate political relationships among the full gamut of adopters. Bronze metallurgy purposed as a military emblem and political tool can be seen as a powerful magnet in its transfer across many geographic, linguistic and cultural divides.

Although pragmatic considerations such as political advantage and military prowess were in all probability instrumental in the propagation of bronze industries in Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet, these were undoubtedly manifested in tandem with potent ceremonial and religious factors.* The awe and respect that bronze metallurgy commanded in the late third and second millennia BCE would have engendered a novel ideological universe in order to promote its uptake and utilization. The incorporation of bronze tools, weapons and ornaments into the mythology, cult and solemnities of polities and cultures in Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet was therefore of critical importance.

Recognition of the importance of ideologies and other abstract components of cultures has come full circle in archaeology in recent years. Of relevance to our discussion on how metallurgy might have been spread in the Bronze Age is a recent study by Michael F. Frachetti (2014) entitled, “Seeds for the Soul: Ideology and Diffusion of Domesticated Grains across Inner Asia”, in Reconfiguring the Silk Road: New Research on East-West Exchange in Antiquity (eds. V. H. Mair and J. Hickman), pp. 41–54. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Frachetti examines early evidence in Central Eurasia for the ritual use of wheat and broomcorn barley at Begash, southeastern Kazakhstan, circa 2300 BCE, a site characterized by a fully developed mobile pastoral economy. Wheat and broomcorn millet were also recovered from tombs in Begash and from Xinjiang mortuary sites, pointing to a highly developed network of interactions between Kazakhstan and Xinjiang. There were no signs of the processing of grain at Begash (only two seeds were recovered from a domestic hearth and no caches were detected). Thus, Frachetti believes that ideological factors were important in the spread of these two crops across Inner Asia, along an east-west communications channel spanning deserts and mountain ranges he calls the “Inner Asian Mountain Corridor”.

For the earliest direct evidence of wheat cultivation in China (ca. 1800 BCE), and the importance of the Hexi Corridor in the transmission of this crop eastwards, see Flad, Rowan / Li Shuicheng / Wu Xiaohong / Zhao Zhijun. 2010: “Early wheat in China: Results from new studies at Donghuishan in the Hexi Corridor”, in The Holocene, vol. 20 (no. 6), pp. 955–965. Los Angeles: Sage Journals.

The spread of wheat to northwestern China has a positive correlation with the diffusion of bronze metallurgy, perhaps as part of a package of food crops and materials emanating from Central Asia.

Whether it was socketed celts and spearheads, awls and daggers with bone handles, earrings with flared ends, or any other class of bronze object found in Xinjiang, northwestern China or far eastern Tibet, each entailed considerable intellectual investment by a people to confer religious value and symbolic import as well as historical meaning, social relevance and magic power upon it.*

Intriguing ideas about the mythology and symbolism of metals in prehistoric Tibet were articulated by S. Hummel (1998). As Hummel remarks, because of their command of fire and metals, smiths in many countries were generally thought to be keepers of occult knowledge. Hummel maintains that the divine blacksmith of Tibet, mGar-ba nag-po (now considered an emanation of the Buddhist god rDo-rje legs-pa), corresponds to the fire and lightning deity Hephaestus who forged the weapons of Zeus. A Tibetan tradition holds that mGar-ba nag-po was originally a smith in western Tibet. According to Hummel, the early historical nature of mGar-ba nag-po is visible in mythological traditions of the Na-khi, a people of the Sino-Tibetan borderlands. Like the god of the archetypal blacksmith of the Na-khi, Yu-ma (Tibetan = Wer-ma), rDo-rje-legs-pa has a retinue of 360 members, representing the solar days of a year. This numerical arrangement suggests that cosmic concepts were at play in the cult of the divine smith. Once probably seen as divinities, heroes and founders of clans, smiths were eventually relegated to an inferior position in Tibet. See pp. 6, 7, 20, 42–52 of Hummel, Siegbert. 1998: Eurasian Mythology in the Tibetan Epic of Ge-sar (trans. G. Vogliotti). Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives.

In contemporary tradition, the principal mountain abode of mGar-ba nag-po is situated on the southeastern edge of Upper Tibet. mGar-ba nag-po, an extremely wrathful figure, is one of the most common objects of spirit-mediumship in that vast region. This territorial god (yul-lha) is considered a protector of treasures (gter-bdag) and a warrior spirit (dgra-lha), the patron of those with practical and martial aims. See pp. 18, 38, 302–311 of Bellezza, John V. 2005: Calling Down the Gods: Spirit-Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bon Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet, Tibetan Studies Library, vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. For a 14th century CE account of Tibetan metalworking practices set in the prehistoric era, see Bellezza 2008, pp. 239–242.

Cultural and historical factors associated with the introduction of bronze metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau

Now that we have reviewed the formation of the Lesser Northern Metallurgical Province (LNMP: southern Xinjiang, northwestern China and far eastern Tibet), let us examine questions concerning this entity’s possible impact on the Western Tibetan Plateau (WTP). It must be noted, however, that there is still no incontrovertible evidence for the spread of bronze metallurgy from the LNMP to the WTP.

There has been an informal consensus in Chinese archaeological discourse that metallurgy came relatively late to Tibet, with dates of 800 to 300 BCE being suggested. However, as we have seen, recent archaeological evidence from both southeastern and northeastern Tibet indicates that an Iron Age periodization for this introduction is simply too late.

Bereft of contextual archaeological findings, let us examine the circumstantial evidence for the introduction of metallurgy on the WTP in the Late Bronze Age (1500–800 BCE). By the second half of the second millennia BCE, bronze metallurgy had enveloped Central Asia, Xinjiang, northwestern China, and far eastern Tibet. The WTP is interposed between India and Xinjiang, regions with well developed metallurgical traditions in the Late Bronze Age. The sheer geographic scope of these technological and cultural traditions would make the WTP an outlier in the greater region had they not reached there too. Moreover, a typological study of bronze artifacts from Tibet suggests that bronze metallurgy may have reached the WTP in the Late Bronze Age.

The rock art of the WTP with its mushroom-shaped anthropomorphs, so-called giants, mascoids (anthropomorphs in emblematic form), chariots, birthing figures, and certain big game hunting scenes have numerous analogies in the rock art of Central Asia and north Inner Asia, which is regularly attributed by archaeologists to the Bronze Age. The northern variants are ascribed to the Okunev, Andronovo, Karasuk and other cultures of that time. Providing that this periodization is accurate (many questions around the chronology of rock art remain), cultural contacts between the WTP and regions to the north began no later than the Late Bronze Age.

Fig. 13. Carved chariot with spoked wheels, round car and two draught animals along the pole. Upper Tibet.

Fig. 14. Engraved chariot with charioteer in the square box (the Z-shaped line on the extreme right side is part of another carving). This chariot petroglyph has wheels with 20 or more spokes and is pulled by two horses. Upper Tibet.

The horse-drawn chariot is a particularly significant rock art subject, one frequently dated in the north Inner Asian context to the second half of the second millennium BCE. Many chariot petroglyphs were made using a split perspective (draught animals depicted back to back), presented as seen from overhead. This split perspective is also found at several different rock art theatres in Ladakh and Upper Tibet, reaching as far east as Shentsa (Shan-rtsa) County. However, chariots have not been documented in the rock art of the eastern Changthang or Central Tibet, suggesting that their transmission to the WTP was directly from the north, the closest and most accessible area (to the west, the Himalaya, Hindu Kush and Karakorum form the highest and most extensive knot of mountain ranges in the world). A northern source for chariot rock art is supported by the restricted distribution of mascoids in Ladakh and northwestern Tibet. Had mascoids been transmitted across the vastness of the Tibetan Plateau from the east, they should appear in the rock art record of intervening areas but they do not.*

In the north Inner Asian context, chariot rock art is often interpreted as vehicles used by male warriors and the aristocracy or as conveyances in ritual performances. It is theorized that in the Bronze Age chariots move eastwards from Kazakhstan with cattle-herding cultures. However, no wheeled vehicles have been discovered in Afanasiev, Okunev, Karasuk or Andronovo burials. Most chariot carvings in the Mongolian Altai are situated on boulders on high, inaccessible slopes and could not have been driven in such terrain nor seen from major travel routes. Some of these rock art chariots are depicted with prone drivers. Thus, they may have been used symbolically in local funerary rites. Chariots and carts seem to disappear from Altaian rock art at the inception of the Early Iron Age. For this summation, see pp. 193–211 of Jacobson-Tepfer, Esther. 2015: The Hunter, the Stag, and the Mother of Animals: Image, Monument and Landscape in Ancient North Asia. New York: Oxford University Press.

It should be noted that the largest concentration of chariot rock art on the WTP at Du-ru-can is likewise situated on inaccessible rocky slopes, suggesting symbolic and ritual functions for them as well.

There is now a broad consensus that the introduction of the chariot in China was part of a spectrum of contacts with Mongolia, Central Asia and even territories further west.* A critical body of evidence for these contacts is bronze and gold objects (including earrings and hairpins) in the cultures of northwestern China as early as the early second millennium BCE, which are indicative of Andronovo and Karasuk influences (Shelach-Lavi 2015: 16). Jianjun Mei (2003a: 31, 32) sees rock art chariots of the Altai, Tuva, Mongolia and northern frontier of China as indirect evidence for the steppe road being paramount in the spread of the chariot to the central plains of China in the second half of the second millennium BCE. He questions an alternative scholarly view holding that chariots were introduced from western Central Asia to Xinjiang and then to Gansu and Qinghai, as there was little tangible evidence to support this perspective. However, that no longer seems to be the case.

Two dozen chariot petroglyphs at three different sites in Ruthok (Ru-thog) and Ladakh (La-dwags), regions not more than 300 km from the southwestern rim of the Tarim Basin strongly suggests that Xinjiang was of pivotal importance in the diffusion of knowledge pertaining to the chariot to the WTP. Adjoining Ladakh and Ruthok, Xinjiang is the closest and most approachable region of the LNMP. This adds merit to the theory that there was indeed a main channel of interaction in the diffusion of bronze metallurgy along a western mountain-desert route.

Also of interest is the recurve bow, which is found in the rock art of the WTP including its early phases (see March 2013 Flight of the Khyung). According to Anthony and Brown (2014: 56, 57), the invention of the short recurve bow in eastern Eurasia perhaps around 1200 BCE, provided riders with a versatile and agile weapon that encouraged the institution of mounted warfare. Around the same time, improved arrowheads including socketed types appeared (ibid).

That chariots, mascoids, recurve bows, and other types of rock art associated with bronze-using cultures in north Inner Asia occur on the WTP is of course no guarantee that alternative seminal traits of the Bronze Age such as bronze metallurgy and wheat and barley cultivation were practiced there in the same period. It is possible that the people of Upper Tibet and Ladakh only selected rock art figuration, neglecting other Bronze Age techno-cultural innovations. Nevertheless, I think that the evidence from the rock art record increases substantially the likelihood that western cultivars and bronze metallurgy were adopted in the same timeframe, as part of a material and ideological package that diffused widely in the Late Bronze Age. This would have drawn the WTP into the same circle of intercultural affairs as other parts of Inner Asia and beyond.

Another body of archaeological evidence linking the Upper Tibetan part of the WTP to the archaeology of the Eurasian steppe is standing stones or menhirs with a funerary ritual function. Known as long-stones (rdo-ring) in Tibetan, one or more stones were erected inside enclosures and rows of them were appended to temple-tombs.* The earliest calibrated date associated with these sites is circa the 8th or 9th century BCE (Bellezza 2008: 91), but how and when this non-burial monument developed in Upper Tibet or how long it persisted are still unknown.† The erection of standing stones may possibly be related to the debut of other customs and traditions of Eurasian origins on the WTP in the Late Bronze Age.

For more information on the long-stones of Upper Tibetan including cross-cultural analyses and extensive site surveys, see my:

2014a: Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: A Comprehensive Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Sites on the Tibetan Upland, Ceremonial Monuments, vol. 2. Miscellaneous Series – 29. Sarnath: Central University of Tibetan Studies. Online version: Tibetan & Himalayan Library (THlib.org): http://www.thlib.org/bellezza, 2011.

2014b: The Dawn of Tibet: The Ancient Civilization on the Roof of the World. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

2011: “Territorial Characteristics of the Pre-Buddhist Zhang-zhung Paleocultural Entity: A Comparative Analysis of Archaeological Evidence and Popular Bon Literary Sources”, in Emerging Bon: The Formation of Bon Traditions in Tibet at the Turn of the First Millennium AD (ed. H. Blezer), pp. 51–116. PIATS 2006: Proceedings of the Eleventh Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Königswinter 2006: Halle: International Institute for Tibetan and Buddhist Studies GmbH.

2008: Zhang Zhung: Foundations of Civilization in Tibet.

2002: Antiquities of Upper Tibet: An Inventory of Pre-Buddhist Archaeological Sites on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

2001: Antiquities of Northern Tibet: Archaeological Discoveries on the High Plateau, Delhi: Adroit.

The plain long-stones erected inside low-lying stone enclosures and rows of long-stones appended to mortuary structures of Upper Tibet share a number of morphological parallels to the plain standing stones of far western Mongolia, situated 2000 km to the northeast. The Mongolian variants are thought to date to the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age; see Jacobson-Tepfer, Esther / Meacham, James, E. / Tepfer, Gary. 2010. Archaeology and Landscape in the Mongolian Altai: An Atlas. Redlands: ESRI Press. In Mongolia and southern Siberia over a period of no less than 1500 years (beginning with the carved stelae of the Okunev culture), groups of standing stones were oriented in north-south rows with the two broader faces and the long sides of any framing walls oriented in an east-west direction. Altars or other accompanying structures are found to the east of the rows of standing stones. Almost always, east is the privileged direction of long vistas. This eastern bias is observable in carved monoliths of the Middle Bronze Age, deer stones of the Late Bronze Age and Turkic effigy stones (ca. 350–600 CE). This suggests that there were persistent beliefs regarding the cycle of life and death in ancient north Asia. See Jacobson-Tepfer 2015, pp. 356–362.

There does not appear to be a strong positive correlation between the standing stones of the Mongolian Altai and the deposition of bronze objects, which is probably explained by a non-sepulchral function for these monuments.

In Upper Tibet rows of long-stones and appended funerary structures were also aligned in the cardinal directions but they are oriented in opposite directions. Rows run east-west and the broad sides of menhirs face north-south. Accompanying mortuary temples are situated to the west of the rows of long-stones. Nevertheless, profound vistas are usually located to the east of these kinds of monuments, suggesting that this too was the privileged direction. I have hypothesized that the trajectory of the sun was perceived of as paralleling the passage from life to the afterlife.

Also in the Sayan-Altai region there are rectangular and sometimes ovoid enclosures, often with double-course walls and internal elements that resemble rooms and hearths. These structures appear to have had a non-burial funerary function and to date to the Late Bronze Age. See ibid., pp. 206, 207, 254, 255. Similar enclosures are common in Upper Tibet but they have fewer internal structural elements than those of north Inner Asia.

In addition to an examination of collateral archaeological evidence, the potential infiltration of technologies and ideologies associated with the LNMP (e.g., ceramics production, knowledge of chariots, wheat and barley cultivation) into the bulk of Tibet can be investigated through the comparative typological study of bronze and copper artifacts.* Affinities abound: similarly appearing copper and bronze objects of the thokcha class.† The paucity of archaeological sequenced bronze objects in Tibet, however, precludes the determination of actual cognate forms. At this juncture, the age, source, composition and structure of analogous Tibetan bronzes remain unknown. Spectrographic analysis of thokchas indicates that they are composed of pure copper, arsenical copper, tin-bronze, and leaded bronze (John 2006: 212–229). However, little attempt has been made yet to correlate the composition of thokchas with chronological and geographic parameters. Given these scientific limitations, comparison of thokchas to Bronze Age metallic objects of the GNMP and LNMP remains a tenuous exercise.

The origins of ceramics production on the WTP are unknown. The forms of vessels dating to the Iron Age and Protohistoric period in western Tibet share some affinity with those from Xinjiang. See January 2016 Flight of the Khyung. There are various Neolithic sites with ceramics in eastern and Central Tibet but they have not yet been positively identified on the WTP. For a review of Neolithic ceramics in Tibet, see March 2015 Flight of the Khyung.

Until the dawn of the Buddhist era (ca. 700 CE) Tibetan copper and bronze artifacts share few obvious affinities with objects from tropical India or the Central Plains of China. The relatively late introduction of Buddhism in Tibet is likely to be a major factor in the retention of archaic forms reminiscent of the Bronze Age and Iron Age repertoires.

Among the most common categories of Tibetan bronzes for comparison are plain and patterned mirrors (some with handles and some with fastening loops on the back), buttons with attachment bars on the reverse, and knives with loop handles. My examination of many dozens of Tibetan specimens indicates that buttons, mirrors and loop-handled knives have particular forms that evolved locally. Nevertheless, at this stage of the investigation, none of these objects can be indubitably linked to the Late Bronze Age. On the other hand, certain small buttons, plain mirrors and bronze daggers of Tibetan manufacture are attributable to the Iron Age. Typological and comparative study shows that other types of Tibetan bronze mirrors and buttons should be assigned to still later periods, extending perhaps as recently as 1500 or 1600 CE.

Tibetan bronze objects with Late Bronze Age antecedents

In figs. 11 and 12 (supra, Part 1), we examined a handsome figured mirror in the Amdo Tsegyal collection. A patterned mirror of the Qijia culture has some correspondence in style and design to this thokcha.* Another patterned bronze mirror with the attachment apparatus on the same face as the embossing was found at the Tianshanbeilu cemetery in Xinjiang.† This circular mirror is embossed with four concentric rings with many radial lines cutting across them.‡ Given correspondences with northern types, the Tsegyal bronze may possibly date as early as the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age.

See Bronze mirror, Qijia culture, Gansu. National Museum of China. Photograph by Gary Lee Todd:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronze_Mirror,_Qijia_Culture,_GansuNational_Museum,Beijing.jpg

For photograph of this mirror (and two others) see 2014: Xiyu wen wu kao gu quan ji (ed. Zhongguo Xinjiang Weiwuer Zizhiqu wen wu ju), vol. 36, p. 59. Alhambra: Kruger Publishing House. For a line drawing of same object, see Jianjun Mei 2009, p. 221 (fig. 12.5, no. 29); Jianjun Mei. 2003a, p.17 (fig. 7, no. 29).

Chinese bronze mirrors also customarily bear the embossing and fastening loop on one side but in design and form are different than the Tsegyal thokcha.

A patterned mirror made of tin-bronze ascribed to the Qijia culture, which is described as “with a geometric pattern on the back”, was discovered in the Gamatai cemetery (Jianjun Mei et al. 2012: 38). This site also yielded 48 other copper and bronze objects, mostly consisting of finger rings and buttons (ibid.). However, no excavation report was ever released (ibid.). Gamatai is situated squarely on the Tibetan Plateau in Guinan County (Mang-rdzong). It remains to be determined if classes of thokcha mirrors with the fastening loop on the back are genetically related to the Gamatai specimen.

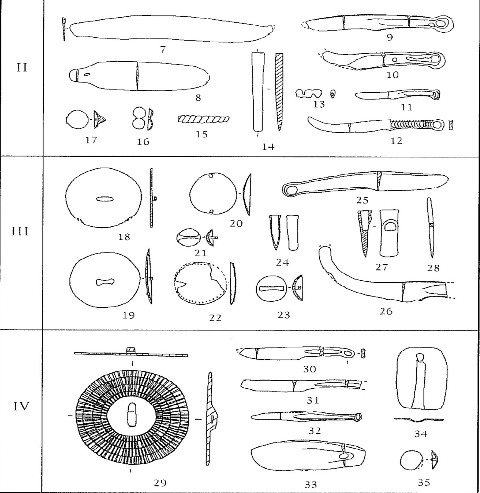

Fig. 15. Copper and bronze artifacts from the Mogou site of the Qijia culture. Of interest in the comparative study of thokchas is the object consisting of two diamond-shaped ends and rounded central portion (no. 12) and curved button with attachment bar on back (no. 14). Image credit: Jianjun Mei et al. 2015: p. 224 (fig. 2); Jianjun Mei et al. 2012, pp. 39, 40 (fig. 4).

Fig. 16. Copper and bronze artifacts from the Tainshanbeilu cemetery, Xinjiang. Of comparative interest are various arched-back cum loop-handled knives, object consisting of double hemispheres (no. 16), flat and curved mirrors (nos. 18–22) and buttons (nos. 23, 35). Image Credit: Jianjun Mei 2003b, p. 53 (fig. 5), after Lū et al. 2001.

Bronze and copper artifacts found at the Tianshanbeilu cemetery in Hami (ca. 2000–1550 BCE), Xinjiang, to which thokchas can be compared include mirrors, buttons and arched-back cum loop-handled knives. These types of knives are similar to those from the Seima-Turbino phenomenon of the eastern Eurasian steppes, indicating some kind of relationship between them (Jianjun Mei 2003a: 20). In the Tianshanbeilu assemblage are plain hemispherical buttons and those with embossed dots along the edge, and flat and slightly curved mirrors with attachment loops on the reverse side (Jianjun Mei 2009: 221 [fig. 12.5]). There are analogous forms among Tibetan thokchas. Also, comparable to a thokcha type is a small bronze object consisting of two hemispheres joined side by side (ibid.). These objects from Tianshanbeilu date to the various phases of the culture. Mirrors with geometric decorations from the Qijia and Tianshanbeilu cultures exhibit local features not seen in the steppes (Jianjun Mei et al. 2012: 42).*

Other bronze objects of Xinjiang and northwestern China similar in form to Tibetan thokchas include:

Jianjun Mei. 2003a:

- P. 4 (fig. 2): arch-backed knife with tiny loop handle of the Qijia culture.

- P. 8 (fig. 5): arch-backed loop-handle knives, slightly curved mirror with attachment ring on back, hemispherical button with rear attachment bar and slightly curved mirror with attachment bar on back of the Siba culture.

- P. 18 (fig. 8, nos. 19, 20): circular button with curved profile and crosshatching around the outer edge, small mirror with two perforations on edge, also arched-backed cum loop-handled knives. These are copper and bronze artifacts from Tianshanbeilu cemetery.

Several Tibetan bronze mirrors and buttons with stylistic and design affinities to northern bronze cultures are presented below. The provenance of these Tibetan artifacts is unknown. Most seem to postdate the Bronze Age and are probably best seen as having been influenced by metallurgical traditions circulating around north Inner Asia in the Iron Age, which were themselves inspired by Late Bronze Age cultures of the LNMP.

Basic bronze forms bridging the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age had a long life history in various cultures of Inner Asia.* Certain types of early thokchas even have later cognate forms, indicating that the retention of anachronistic bronze styles and designs was especially pronounced in Tibet. Methods of manufacture may have changed but classes of Tibetan bronze objects such as buttons and mirrors endured. A parallel can be drawn with the rock art of Spiti and Upper Tibet: certain themes (e.g., solo portraits of wild yaks, wild yak hunting, tiered shrines, etc.) were extremely persistent.

For a comparison of bronze mirrors and buttons of the so-called Slab Grave culture (Iron Age) of eastern Mongolia and similar thokcha forms, see Bellezza 2008, p. 103; May 2010 Flight of the Khyung. Most of the thokchas illustrated in these works appear to be vestigial forms that postdate the Iron Age. The Slab Grave specimens can be seen as successors to objects from bronze cultures of the GNMP.

In slab graves of Mongolia the emphasis is on grave goods of non-local origins such as cowries, mother-of-pearl, special types of ceramics, white bronze, etc. See pp. 345, 360, 361 of Honeychurch, William / Wright Joshua / Amartuvshin, Chunag. 2009: “Re-Writing Monumental Landscapes as Inner Asian Political Processes”, in Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility (eds. B. K. Hanks and K. M. Linduff), pp. 330–357. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The presence of exotic materials in slab graves presupposes the existence of a highly extensive network of trade and exchange. Interregional communications incumbent in such a network probably help to explain parallels in bronze objects of the Slab Grave culture and Iron Age cultures of Xinjiang, northwestern China and Tibet.

Fig. 17. Hemispherical mirror with two perforations for attachment. Moke Mokotoff collection, New York.

Fig. 18. Reverse side of object in fig. 17.

Although the general form of this small mirror recalls objects of the LNMP, it belongs to a later period. This type of object is common in the Tibetan repertoire of thokchas, indicating that whatever it’s ultimate origins it came to be closely associated with the Bodic cultural milieu. There are many variations in size, design and style of such mirrors. A typological study suggests that they were forged in Tibet from perhaps the Iron Age to at least the Early Historic period.*

For two other examples of this class of thokchas, also see Lin Tung-kuang 2003, p. 35 (top, upper left).

Fig. 19. Hemispherical mirror with a band of embossed ‘eyes’ (mig). Note the perforation in the object made so that it could be suspended. Such mirrors were worn on the headgear and over the mantles of Tibet sprit-mediums. Moke Mokotoff collection, New York.

Fig. 20. Reverse side of object in fig. 19.

Mirrors with a series of eyes circumscribing the edge of the object in many different styles are another common form in Tibetan thokchas. They were probably naturalized in Tibet in the Iron Age and continued to be produced until the Early Historic period or Vestigial period (1000–1300 CE). The Mokotoff specimen can be attributed to a middle phase in the production of this genre of bronze mirrors.*

For another Tibetan specimen, see Bellezza 1998, p. 52 (fig. 4). Similarly, a parallel line of historical continuity is recognizable in bronze mirrors with an analogous ‘eye’ motif of various Scythic cultures. For example, see p. 113 (fig. 22, c) of Dvornichenko, Vladimir V. 1995: “Sauromatian Culture”, in Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age (eds. J. Davis-Kimball, V. A. Bashilov, L. T. Yablonsky), pp. 105–119. Berkeley: Zinat Press. Also see p. 311 (fig. 18, f–i) of Bokovenko, Nikolai, A. 1995a: “The Tagar Culture in the Minusinsk Basin”, in Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age (eds. J. Davis-Kimball, V. A. Bashilov, L. T. Yablonsky), pp. 299–314. Berkeley: Zinat Press.

Recognition that the WTP had contacts with the Scythic world, as determined through comparison of a bird thokcha with northern bronze objects, was already made more than 30 years ago. See Koenig, Gerd, G. 1982: “Skythen in Tibet?” in Der Weg zum Dach der Welt (eds. C. C. Müller and W. Raunig), pp. 318-320. Innsbruck: Pinguin-Verlag.

Fig. 21. Disc with slightly raised center surrounded by two rings punctuated with square nubs and an outer band of triangles. Bob Brundage collection, USA. Photo: Bob Brundage.

Fig. 22. Reverse of disc in fig. 21. Note the four raised bands of metal used, it appears, for fastening the object to something else. Photo: Bob Brundage.

This object was presumably made somewhere in Tibet and appears to belong to the earliest horizon of metallurgy on the Plateau.* If any Tibetan patterned bronze mirrors are of Late Bronze Age antiquity, it is one like this that seems most eligible for this attribution.

This object was first published in Bellezza 1998, p. 63 (fig. 70).

Fig. 23. Button with cruciform design, central nipple and four surrounding dots. Bob Brundage collection, USA. Photo: Bob Brundage.

Fig. 24. Rear of button in fig. 23. Photo: Bob Brundage.

This button appears to belong to an early phase of Tibetan bronze metallurgy. I have selected this specimen for illustration here because it may possibly date to the Late Bronze Age. Buttons, especially plain ones with hemispherical forms and more flattened profiles and various kinds attachment loops on the rear were commonly produced in Tibet over a long swathe of time.* Some Tibetan buttons have prominent attachment bars recalling those of the Qijia and Tianshanbeilu cultures.

For images of Tibetan bronze buttons, see Lin, Tung-Kuang. 2003, p. 163; John 2006, p. 176 (fig. R-609).

Fig. 25. Thokcha talisman consisting of two joined hemispherical forms. Moke Mokotoff collection, New York.

Fig. 26. Back side of copper alloy object in fig. 25. Note the two attachment rings which are now broken.

While the earliest objects of this general form belong to the LNMP, comparable artifacts of a more recent date are known in both the Tibetan and the Scytho-Siberian worlds.* This type of thokcha was discovered in an Iron Age burial of western Tibet.† Others are reported by dealers to have been procured in the same region. They come in numerous styles which in aggregate constitute a distinctive class of Tibetan bronze objects.

For two other examples of this type of thokcha, see See Lin 2003, p. 122. For examples of analogous objects in horse halters of Scytho-Siberian cultures of the Iron Age, see pp. 240 (fig. 2), 305 (figs. 4, 5, 11) of Shulga, Peter I. 2015: “Saddle Horse Gear in Mountain Altai and Upper Ob Area, Part II (6th–3d B.C.)”. Novosibirsk: Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (in Russian).

See Huo Wei 2014, p. 330 ( fig. 9). This object was discovered in a tomb of the rGya-gling cemetery, Guge, which is dated to the second half of first millennium BCE.

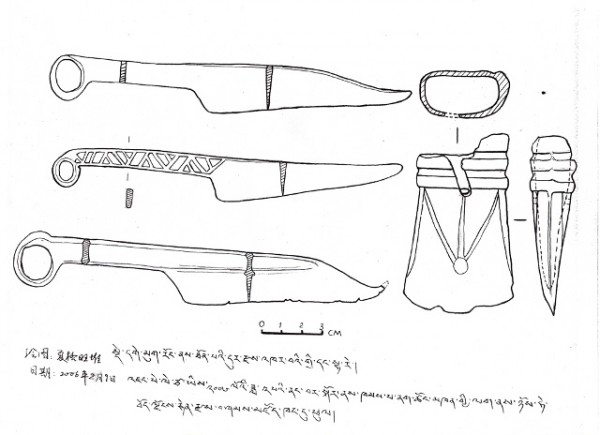

Fig. 27. Line drawings of three knives and axe head, Tibet Museum, Lhasa, 2006.

Fig. 28. Photograph of the three knives illustrated in fig. 27.

Of special interest in investigating the penetration of northern bronze metallurgical traditions into the the Tibetan Plateau are three bronze knives and an axe head procured in one lot from the Tibetan antiques market in 2006. I purchased these artifacts with monies donated by the Tibetan Medical Foundation with the express intention of donating them to the Tibet Museum (Bod-ljongs rten-rdzas bshams-mdzod khang) in Lhasa. They help fill a void in the museum’s scanty pre-Buddhist holdings. Even today there are few bronze objects in the Tibet Museum dating to what the Chinese call the ‘Early Metal Age’ (an ambiguous chronological categorization). I was given a receipt by the Tibet Museum containing drawings of the three knives and axe, background information I obtained from the seller, and a record of the date of my donation. Unfortunately, the knives and ax have still not been put on display.

According to the seller, the three bronze knives were discovered in a cist grave in Dege Mukrong (sDe-dge Mug-rong), situated near the eastern bank of the ’Bri-chu (Upper Yangtze River). In this region the ’Bri-chu forms the boundary of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Tibetan areas (Khams) incorporated into the Chinese province of Sichuan. These bronze objects are noteworthy for the putative location of their discovery. To my knowledge, loop-handled knives in this region have not been reported in academic literature.

Although the three knives have clear affinities with those found in Xinjiang and northwestern China, they constitute a distinctive class of knives whose manufacture is probably attributable to the wider region in which they were reportedly found. Only the upper specimen in fig. 27 can be called arch-backed. The other two have straighter spines. All three knives have turned up points, a distinguishing feature of this class of knives, bringing them into alliance with Mongolian variants.* The middle specimen has a ribbed handle forming a geometric design of rectangles and triangles. All three weapons have prominent loops at the end of the handle. These knives are well designed and stylistically well evolved.† On cross-cultural grounds, they can be assigned to the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age (900–600 BCE).

For arched-back knives with upturned points (with and without loop handles) from Mongolia, see p. 322 (figs. i, k, j, m) of Volkov, Vitali, V. 1995: “Early Nomads of Mongolia”, in Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age (eds. J. Davis-Kimball, V. A. Bashilov, L. T. Yablonsky), pp. 319–333. Berkeley: Zinat Press. These are dated by Volkov (ibid., 321) to the Late Bronze Age. Although these Mongolian knives share major design features with the Tibetan knives, they belong to culturally different groups of artifacts. Arched-backed cum loop-handled knives of Tuva, the Minusinsk Basin and the Sayan-Altai also exhibit distinctive regional characteristics. Categorical differences in loop-handled knives seem to mirror significant cultural, linguistic, ethnic variability in Inner Asia, Tibet included.

For a dagger in an entirely different style also dated to the Early Iron Age (800–500 BCE), reported to have been found in Nang-chen (northeastern Khams), see p. 408 (fig. 2) of Ronge, Namgyal G. 1988: “Thog-lčags of Tibet” in Proceedings of the 4th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies. Schloss Hohenkammer – Munich 1985 (eds. H. Uebach and J. L. Panglung), pp. 405–412. Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. This is a double-edged dagger with a symmetrical blade, prominent central spine and handle with geometric design (consisting of six concentric circles contained in squares), pointed guard and broad pummel. The fine form and finishing of this dagger shows that it belongs to a mature metallurgical tradition. Ronge (ibid., 427) comments that it has similarities to ones discovered in the Ordos but that it is likely to be of Tibetan manufacture.

The blade and handle of the Ronge dagger are indeed comparable to Scythian types. For example, see Saka bronze dagger with somewhat similar form and design characteristics from the Tamdinski cemetery, Pamirs (dated to 8th–6th century BCE): p. 236 (fig. 100, d) of Yablonsky, Leonid, T. 1995: “The Material Culture of the Saka and Historical Reconstruction”, in Nomads of the Eurasian Steppes in the Early Iron Age (eds. J. Davis-Kimball, V. A. Bashilov, L. T. Yablonsky), pp. 200–239. Berkeley: Zinat Press. Also see Tagar culture daggers from the Minusinsk Basin in Bokovenko 1995a, p. 304. For comparable daggers from Mongolia see Volkov 1995, p. 322 (fig. e).

Unlike the more universally designed buttons and small mirrors examined above, the defining morphological and stylistic traits of these knives furnish sufficient evidence to assign them to LNMP.* The three knives from Dege Mukrong can be seen as epitomizing the geographical and chronological extension of the LNMP deep into Tibet, where it was transformed or indigenized in a remarkable fashion. The existence of these knives adds weight to the view that the bronze buttons and mirrors of Tibet were also inspired by the LNMP. These affinities demonstrate that there was indeed intercourse between north Inner Asia and the Tibetan Plateau (not just far eastern Tibet), beginning as early as the Late Bronze Age. This should come as no surprise because lines of trade and communications across the Tibetan Plateau are relatively open. The loop-handled knives of Dege help establish the antiquity of these pathways.

An arched-back knife with loop handle is unique among a group of northern bronze objects illustrated (see Shelach-Lavi, p. 17, fig. 2.1). This knife may possibly have come from Tibet. If this is shown to be the case, it demonstrates that there was movement of Tibetan metallic items north to the LNMP. However, exceedingly few bronze objects from the WTP and Central Tibet appear in northern assemblages, intimating that any such importation was uncommon. On the other hand, the widespread distribution of cowries and carnelian beads suggests that there were well established avenues of trade linking Tibet with north Inner Asia in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Like the three knives, the socketed axe head from Dege Mukrong (fig. 27) also appears to be distinctively Tibetan and of Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age antiquity. The mouth of the socket is reinforced by two ridges of metal that circumscribe it.* This ribbed socket is a distinctive feature of Tibetan axes. The blade of this tool has decorative tracing. I have seen similar axes and those with rounded rather than wedge-shaped heads for sale in the Tibetan antiques markets.

For axes with a similar style wedge shape and socket design but without decorative embossing on the sides, see Ronge 1998, p. 47 (fig. 1); John 2006, pp. 172 (figs. R-576), 206. According to a report received by Ronge (ibid.), the ax and two copper rings came from the Tsangpo (gTsang-po) valley of Central Tibet. If this geographic information is reliable, it indicates that wedge-shaped bronze axes were used over a large portion of the Tibetan Plateau, as one might expect of a utilitarian implement of elementary design. Ronge (ibid.) assigns the ax to 1800–1200 BCE. If there is any merit in his dating of these objects so early in the Bronze Age, they are very important signposts for determining the origins of metallurgy in Tibet. However, it must be kept in mind that axe heads, like simple bronze buttons and discs, are utilitarian objects that cannot be dated on form alone, as styles and designs were recycled over a long period of time.

Tibetan copper and bronze objects analogous in form to northern examples of the Late Bronze Age seem to typify the long-term persistence of certain styles and designs on the Plateau. Therefore, we might see Tibetan variants as historical offshoots in a convoluted trajectory ultimately originating in the LNMP. If any mirrors, buttons and knives or other copper and bronze objects produced on the WTP or in Central Tibet actually date to the Late Bronze Age, they are best accounted for as directly resulting from contacts with technologies, ideologies, peoples and objects of the LNMP. For those aspects of the material culture of the WTP and Central Tibet that arose in the Iron Age, bronze-making traditions in various northern regions and cultures of that period must be sought out.

After exposure to Bronze Age and/or Iron Age metallurgical traditions from the north, the WTP and Central Tibet went on to devise their own technological and esthetic idioms. The distinctive forms of Tibetan knives, mirrors and buttons are surely the product of local innovation, albeit one that borrowed from prototypic objects, skills and ideas emanating from the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Xinjiang or other northern regions. These kinds of bronze objects on the WTP and Central Tibet were transformed through acculturation and technological indigenization. Attenuated by the size and distinctiveness of Tibet, the northern bronze traditions so conspicuously seen in the eastern steppes, Xinjiang, northwestern China, and far eastern Tibet arose as something new, metallurgical systems peculiar to the WTP and Central Tibet.

Thokchas and other bronze objects (vessels, fittings, figurines, etc.) belong to an unique ensemble of cultural, technical, economic and environmental features clearly recognizable as Tibetan. Thokchas retained old-fashioned features well into the historical era (post-630 CE), one of a number of indications of an inherent conservatism in Tibetan cultures and their retention en masse of archaic customs and traditions.*

This conservatism is evident in both the literary and ethnographic records, pointing to the durability and robustness of certain traditions in Tibet. It is important to add however that this does not negate significant cultural development and change in other areas. It is also worth noting here that Tibet did not and does not have a single culture. According to a prevalent tradition in Tibetan historical literature, there were a number of major languages and polities on the Tibetan Plateau before the Imperial period (ca. 630–850 CE). These included entities such as Zhang Zhung (Upper Tibet), Sum-pa (north central Tibet), sPu-rgyal bod (Central Tibet), A-zha (northeastern Tibet), Mi-nyag (far northeastern Tibet), lJang (southeastern Tibet), and Mon (southern Tibet). It is recorded in Tibetan literature that before the time of these proto-states, Tibet was ruled by a succession of chieftains, human and nonhuman. While these accounts of Tibet’s cultural and political past are heavily mythologized, they do encapsulate historical lore. To this day there are some 40 languages and major dialects on the Tibetan Plateau, including those that are linguistically non-Bodish and even languages that are non-Tibetic (such as the Qiangic languages of rGyal-rong). As we speak of Persian, Indian or Chinese civilization, so too its Tibetan manifestation.

This article furnishes evidence to indicate that the WTP and Central Tibet were influenced by cultural and technological activities connected to the LNMP. The intensity and nature of this influence, however, cannot be assessed until more archaeological data become available. We can reasonably assume that metallurgical traditions established in far eastern Tibet travelled further west, transferring technological and cultural elements to the Tibetan hinterland. Moreover, the WTP probably received an LNMP bequest from the Pamirs, Tarim Basin or other western regions. Rock art attributed to the Bronze Age located on the western parts of the Tibetan Plateau supports this assertion. The standing stones of Upper Tibet may have been part of the same package of Late Bronze Age technological and cultural traits imported onto the WTP from north Inner Asia. Barley, wheat and peas as belonging to the same suite of Late Bronze Age inputs on the WTP must also be given serious consideration.

What is needed now is the smoking gun: the discovery in archaeologically secure contexts of bronze artifacts, botanical and zoological specimens, and other materials of Bronze Age antiquity on the WTP.

Bronze metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau and adjoining regions in the Iron Age

While there is still scant evidence with which to adduce the introduction of copper and bronze metallurgy on the Western Tibetan Plateau (WTP) in the Late Bronze Age, there is considerably more to go on for the Iron Age. A growing body of Tibetan bronze objects attributable to the Iron Age permits us to develop a sharper picture of interactions between the WTP and north Inner Asia in that period.