October 2011

John Vincent Bellezza

The latest in Tibetan archaeology

This month’s Flight of the Khyung returns to the International Conference on the Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau, held between August 21 and August 24 in Chengdu, China. This issue is fully devoted to new archaeological discoveries made in western Tibet and other important matters presented at the conference. We take up exactly where we left off last month; that is, with the second and third days of the proceedings. As already noted, I am only able to provide a review of select presentations in this newsletter.

- Mark Aldenderfer (School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Art, University of California, Merced) et al.: Transhimalayan migrations in upper Mustang

Professor Mark Aldenderfer began by bringing our attention to longstanding questions concerning the movements of people in the Himalaya and surrounding regions. In order to answer these questions more focused interdisciplinary studies of Himalayan migrations are required. For no less than 3000 years, migrations to Mustang have been taking place, some of which are likely to have been tied to the salt trade. In the 1100 to 1600 CE timeframe, a historically documented migration of people from Tibet to Mustang took place. Many of these residents lived in caves hewn from the formations; some so tall and intricate that they can be described as ‘apartment complexes’. As for earlier periods of tenure in the region, there is the Chokhopani (1200–450 BCE) and Mebrak (450 BCE to 50 AD) periods. The site of Samdzong was occupied circa 400–500 CE. Rather than open cavities, there is physical evidence to show that many burials consisted of shaft tombs.

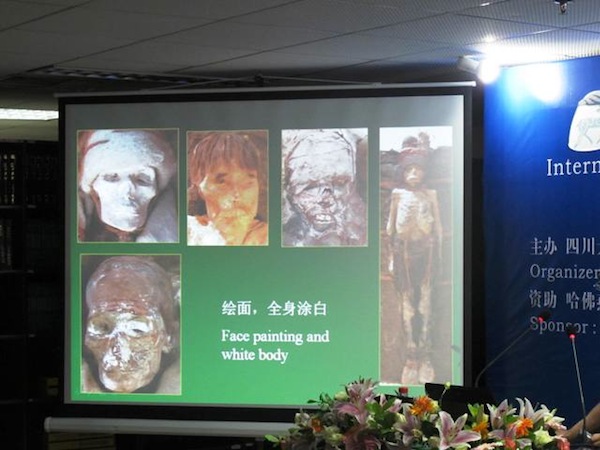

At Mebrak, it is the upper ‘caves’ that had mortuary functions. Defleshing of corpses was widely practiced as indicated by cut marks on the bones. Professor Aldenderfer sees this as possibly being a precursor to sky burial practices of the historic era. Many tombs contain the full range of age groups and both sexes.

Genetic studies of mitochondrial DNA recovered from human remains at Mebrak demonstrate that the population was relatively cosmopolitan. The haplogroups M3, M4 and M25 are specific to the Indian Subcontinent, while the haplogroups M10, D4 and D45 are of Tibetan or east Asian origins. The analysis of strontium isotopes from dental enamel, a signal of where a person was born, indicate that most of the population was native to Mustang (note: place of birth may have little to do with genetic ancestry). One individual from the Samdzong site that underwent molecular analysis had a genome remarkably similar to that of an early Bronze Age person from Xinjiang. Copper beads found at this site are probably of southeast Asian origin.

Although the scientific data reflects various human movements in Mustang, hard evidence directly linking the region to Tibet has yet to be compiled. However, metal artifacts found in the tombs are yet to be sourced.

My comments: The widespread use of what appear to be mountaintop ossuaries in the western Changthang (Byang-thang) is another example of disposal were defleshing or desiccation must have taken place. I relate these Upper Tibetan burials to the practice of excarnation, whereby enshrined human bones were invested with magical / sacred properties. As for the placement of shaft tombs at the tops of the cave complexes, this is liable to be related to Tibetan archaic eschatological beliefs concerning skyward passage to the celestial afterlife.

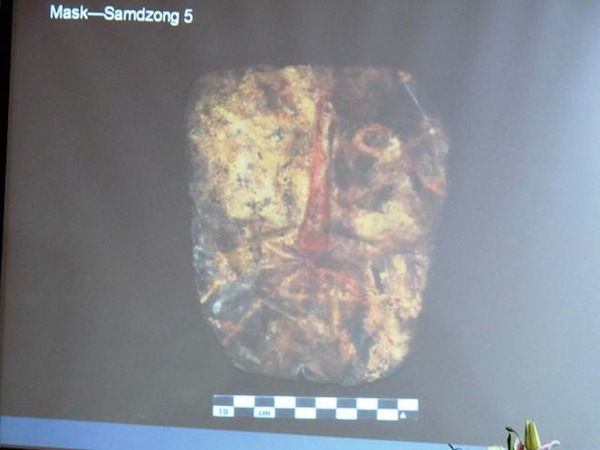

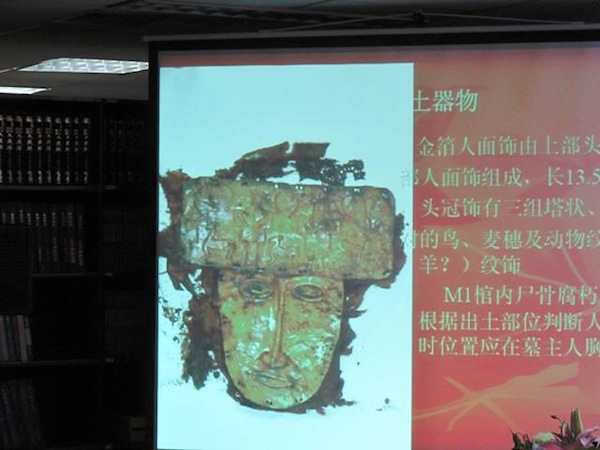

Fig. 1. The gold mask from Samdzong, Nepal. From the presentation of Mark Aldenderfer

- Tong Tao (Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences): Archaeological data for cultural exchange between west Tibet and south Xinjiang before the imperial Tibet period – significance of Kaerdong cemetery

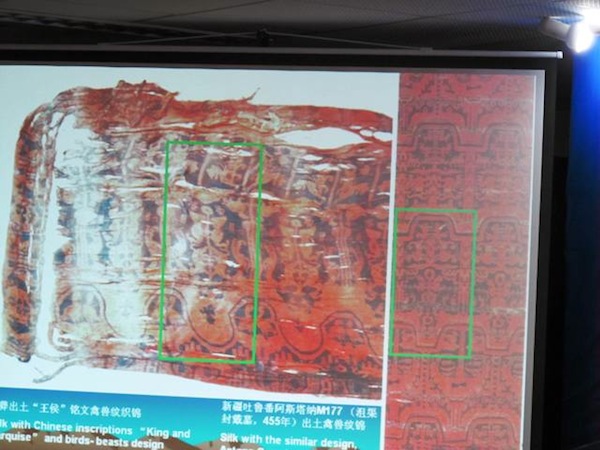

Dr. Tong Tao observed that a silk from the Astana cemetery in Xinjiang dated to circa 455 CE has the same two-color scheme and broad design parallels with the silk recently discovered at Khardong (Mkhar-gdong). Another comparable silk was discovered in the Yuli cemetery, Xinjiang. Dr. Tong believes that the copper alloy vessels found in the Khardong burial were imported from Xinjiang. Gilt silver fragments were also recovered from this burial. Dr. Tong compared a perforated wooden slip from Mazar Tagh with wooden fragments from the Khardong burial. On a circular wooden vessel found at Khardong there are traces of paint. Dr. Tong sees the woven cane object recovered at Khardong as being a basket. A grave good that points to Transhimalayan trade links cited by Dr. Tao is birch bark. The wooden combs found in the Khardong burial are similar to those found in Xinjiang. In Xinjiang, those combs with a rounded form can be dated to the 3rd to 5th centuries CE. Dr. Tong compared the ceramics of the Khardong burial to those from far afield. He theorizes that this was a princely burial of Zhang Zhung. He further notes that the funerary objects indicate the formation of a pathway of communications to Xinjiang.

My comments: I concur with Dr. Tong Tao’s general conclusions that the Khardong burial was of an individual with a high occupational rank and/or high social status and that it has cultural affinities to Xinjiang. It should be noted that this burial is actually located at Gurgyam (Gur-gyam) and not Khardong. Dr Tong’s comparisons with specific silks discovered in Xinjiang is also helpful (although the Gurgyam specimen is somewhat older). My preliminary assessment is that the copper alloy vessels of the so-called Khardong burial are of local manufacture. Sanctioned and illegal excavations in western Tibet have consistently turned up protohistoric metal objects of a very high manufacturing and esthetic standard (including types like those found at Gurgyam). Moreover, geometric and zoomorphic ornamentation on metal objects found in western Tibet is in an indigenous style. Nevertheless, a detailed typological study of copper alloy vessels is needed to definitively fix the provenance of the Gurgyam examples. The wooden slip from Mazar Tagh, a Tibetan record keeping device (byang-bu) from the imperial period occupation of Central Asia shown in Dr. Tong’s presentation, is not directly comparable to wooden objects found at Gurgyam, for the latter date to the protohistoric period. As for the ceramic assemblage of the Gurgyam burial, it is most comparable to those recovered from other western Tibetan mortuary sites. Finally, I should point out that the woven cane item appears to be a shoe, and is excellent evidence for Transhimalayan trade links having existed in the time of the burial (circa 300 CE). For more information on the Gurgyam interment and its radiocarbon date, please see my October 2010 newsletter.

Fig. 3. The silk from the Gurgyam burial (left) and one from Xinjiang, PRC. From the presentation of Tong Tao

- Vinod Nautiyal (Dept. of History and Archaeology, HNB Garwhal University): Archaeological, geophysical and scientific investigations of high mountain cave burials of Malari, Uttarakhand Himalaya, India

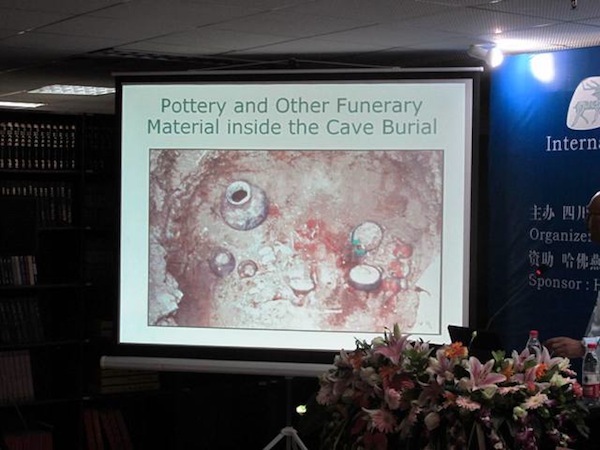

Malari is the name of a village and archaeological site in the Alaknanda valley of the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand. There are a number of archaeological sites in the Alaknanda valley that can be broadly dated 1000 BCE to 800 CE. Some ceramics recovered from this region are of a type associated with the plains of India. This appears to indicate that peoples from the plains had begun to move into the Uttarakhand Himalaya by 1000 BCE. The burials of Malari were hewn from calcareous formations and the mouths of the graves were blocked by large boulders. These burial chambers measure around 1.5 m x 2.5 m. In one burial the complete skeleton of a yak hybrid was found. At burial sites in Khinga, Nepal, skeletons of yak hybrids were also discovered. As a beast of burden, the hybrid yak was venerated by the cultures that carried out these burials. Also, skeletal remains of a juvenile human were discovered in the Malari cave burials. Carbon isotopic analysis of these remains is now being conducted in an attempt to reconstruct the paleodiet of the region. In order to survey the region more thoroughly, magnetic gradiometry is being carried out.

Recently, during road construction, cist burials were discovered along the bank of the Sutlej river, below Kunam village in Himachal Pradesh. Among the burials was an entire human skeleton, dated to circa 2300 BCE. Professor Vinod Nautiyal theorizes that the burials of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Mustang and western Tibet of circa 2000 to 2700 years ago represent an interrelated cultural regime.

My comments: Finally, after so many years the archaeological evidence from the Central Himalaya is starting to build in both quantity and quality. Hopefully, this is the beginning of a period of more intensive and more rigorous investigation of the region. While cultural affinities between far-flung Himalayan valleys can be divined, improved scientific methodologies are required to determine the true nature and extent of interregional cultural and demic correspondences.

I would like to suggest an alternative hypothesis to explain the deposition of hybrid yaks (mdzo) in the tombs of the Central Himalaya. According to Old Tibetan funerary documents (written circa 700–1000 CE, but harking back to earlier times), hybrid yaks were sacrificed as offerings to appease the demons of death, freeing the dead to make the journey to the afterlife. Female hybrid yaks and steeds were also used as mystic vehicles for the transport of the dead (females and males respectively) to the otherworld.

Fig. 4. The grave goods from a burial in Malari, Uttarakhand, India. From the presentation of Vinod Nautiyal

Fig. 5. The golden burial mask discovered in Malari. Photograph courtesy of Vinod Nautiyal

- R. C. Bhatt (Dept. of History and Archaeology, HNB Garwhal University): Malari cave burials, funerary gold mask and evolved ceramic tradition in Uttarakhand Himalaya, India

Professor R. C. Bhat began his presentation by stressing trade links between Malari and western Tibet that existed until 1962. The Painted Greyware culture of north India extended into the hills of the Ganga-Yamuna doab. However, the black and redware of the north Indian megalithic burials is not known in these Himalayan foothills. Some ancient ceramics recovered in Uttarakhand have strong affinities with the Gandharan grave culture of Swat. There are fine examples of this type of ceramics from the Malari cave burials. Also copper utensils were recovered from these tombs. Professor Bhat believes that a gold mask found in a Malari grave is of royal significance. This mask (8 cm x 7 cm) is made of beaten gold less than 1 mm in thickness. It may have been formed from an impression. A gold pendant was also found in Malari.

My comments: The facial features and shape of the head of the Malari burial mask are not unlike wooden and metal masks from western Nepal, which were used for worship, protection and ritual purposes. The Nepalese masks, however, date from after the 16th century CE. It should be possible to historically trace the anthropomorphic form in the art of the Central Himalaya more closely.

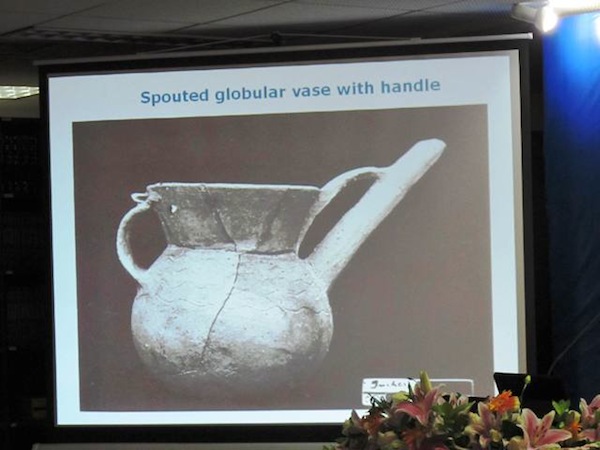

Fig. 6. Ceramic pot with supporting arm over the spout. From the presentation of R. C. Bhatt

- Lin Linhui (Tibet Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology): New archaeological discovery found in Ngari, Tibet: Quta cemetery

In his presentation, Dr. Lin Linhui showed a map with 40 archaeological sites of various types and periods in far western Tibet. Recently, two tombs were discovered in Guge (Gu-ge) during road construction. The Quta cemetery is close to the famous monastery of Tholing (Mtho-lding). Tomb M1 (approximately 5 m²) consists of a pit and passageway to the surface. A wooden coffin was found on the south side of the grave pit. Among the human remains was a mask (13.5 cm in length), which Dr. Linhui speculates may have been used as a pectoral ornament. An iron arrowhead and ceramics similar to those discovered on the other side of the Himalaya were found in Tomb M1. Ceramic amphorae were also deposited in this tomb. Tomb M2 consisted of a single chamber containing a mortuary crib upon which rested two flexed corpses. Ceramics and weaving implements were placed in the tomb. Dr. Lin noted that the ceramic vessels with high pedestals are similar to those found in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. In some ceramics there is a white powder residue. To the left of the burial there was a peach-shaped box, to the right of the burial lay a square stone tray. Also, ironware, gold ware, weapons and ornaments were discovered in Tomb M2.

Dr. Lin compares the Quta burials to those of Khardong, Kharpoche (Mkhar-po che) and Gebusailu, dated to circa 2600–2100 years before present. The earliest of these cemeteries was Gebusailu, which like Quta has shaft tombs. However, while some gold objects were discovered in Gebusailu its tombs did not contain wooden coffins. According to Dr. Lin, the Quta burials are about 2000 years old.

My comments: Dr. Lin Linhui was so generous as to give me a copy of his entire power point presentation, so that I could inspect his discoveries in more detail. I heartily thank him for it and hope that some of my comments might prove useful. Clearly, the Quta site is one of the most important tomb discoveries made in western Tibet, a huge contribution to ongoing archaeological inquiry in the region. The excavation of the two Quta tombs was a salvage operation, in which the priority was to save significant material objects from oblivion. In what way organic and inorganic objects were deposited in the tomb and subsequently collected remains to be disclosed.

When the conference members saw the ceramics and mask from the Quta burials an exclamatory sound rung out across the hall. It was plain for all to see how much these objects resembled those found in Malari. This of course reflects certain technological and cultural affinities between these two funerary sites straddling the Himalaya, but the precise nature of their interrelationship is yet to be determined. Axiomatic in archaeology is that just because objects from different sites resemble each other this does not necessarily mean that those who made and used them shared the same life-ways, language or history. It is even possible that a culture Y and a culture X, although sharing close material cultural correspondences, did not even know of each other’s existence, let alone have direct lines of communication. Still, despite these admonitions, I think it is likely that the peoples of the Quta and Malari burials enjoyed cooperative economic and cultural relations. Material cultural analogues can be accounted for in sundry ways having to do with trade, political alliances, hegemony, vassalage, diplomacy, ceremonial transfer of prestige objects, and concurrent interregional / intercultural trends in the exercise of technical and design information, among other mechanisms that inform parallel material cultural development.

Dr. Lin believes the Quta mask is composed of gold but he was not certain. From the photograph available to me, the mask appears to be made of a thin layer of gold applied over a silver base. Likewise, Dr Lin could not say what the substances attached to the edges of the mask were. In any case, they appear to have included a textile. Dr. Lin indicated that an analysis of the Quta grave goods is now underway.

The mask consists of two sheets of metal connected to one another through a series of linked holes. Leather throngs may have been used to tie the two sheets together, but we must await more information and better photographs to know for certain.

The lower sheet of the mask is a likeness of the human face. It exhibits somewhat similar features to the Malari mask: a long nose, lips simulating the faintest of smiles and wide oval eyes. These facial features do not appear to be very Mongoloid. In Upper Tibet, the oral tradition abounds with tales of the Mon, an ethnic group believed to be of Himalayan stock that is supposed to have controlled much of the Changthang and western Tibet in ancient times. The Bon textual tradition for its part maintains that in prehistoric times bon priests were active in both the temperate Himalaya and in Upper Tibet. Given the countenance of the mask and the Tibetan cultural traditions, one possible hypothesis is that at least some of the social elite of western Tibet some 2000 years ago were indeed of cis-Himalayan origins.

The upper plate of the Quta mask is rectangular and is ornamented with two rows of repoussé animals. The lower row consists of three wild ungulates that resemble blue sheep, each facing to the left. Each of these animals occupies the bottom portion of a three tiered object surmounted by a bulbous structure. These are representations of ceremonial structures known in Tibetan literature as a sekhar (gsas-mkhar), tenkhar (rten-mkhar) or lhaten (lha-rten). According to a Bon text from the Ge-khod cycle, these elementary tiered shrines were first used in the Upper Tibetan kingdom of Zhang Zhung in pre-Buddhist times (see my book Zhang Zhung for more information). These types of shrines (complete with the bulbous upper section) abound in the rock art of highland Tibet. They are also known in the form of stone and metal models and miniature copper alloy talismans. In my writings, I have consistently maintained that tiered shrines may have originated long before Buddhism and stupas gained a foothold in Tibet. The discovery of embossed variants on the Quta burial mask shows this to be the case (but let us await chronometric data from the burial to make this official). What was unknown until the Quta mask came to light is that some of these ceremonial structures had funerary ritual significance. In Bon literature, they are assigned with cosmological and deity enshrining functions. The upper row of the upper plate is comprised of six birds: two confronted pairs in the middle and solitary birds at either end of the row. This line of avian figures is set between the upper sections of the three shrines. These birds may represent aquatic species or possibly cranes. Various birds and wild ungulates are well attested in the Tibetan archaic funerary tradition. Stylistically, these animals are comparable to both Upper Tibetan rock art and zoomorphic talismans known as thokchas (thog-lcags). Between one confronted pair of birds there is what appears to be a tree.

As for the function of the Quta mask, I am inclined to see it as a likeness of the deceased used for ritual purposes. The Tibetan archaic ritual tradition places much stock in the ‘golden face’ (gser-zhal), which was used as a receptacle for the soul of the deceased during the evocation rite held before burial. According to Bon religious tradition, this object consisted of a facsimile or effigy of the departed (see Zhang Zhung for further information). It may therefore be the case that the golden burial masks found in Guge and the high Himalaya are the precursors of this type of imperial period funerary ritual instrument (interestingly, the origins myths attached to the explication of the funerary ritual armory are often set in primal or prehistoric times). The embossed animals on the mask may well be representations of the zoomorphic spirit allies that were believed to usher the dead to the afterlife (for more on these pyschopomps, see my forthcoming book, Death and Beyond in Ancient Tibet). These zoomorphic deities helped protect the dead from the predation of the demons of death, malevolent beings intent on keeping the deceased in their clutches. The embossed tree appears to be another type of soul receptacle. In the textual tradition, a juniper tree usually fulfills this function. The Quta and Malari burial masks (also the one discovered in Samdzong, Nepal) were probably placed over the face of the deceased, a practice found in a variety of Eurasian funerary cultures. The Quta mask suggests that a textile shroud was originally attached to perforations around the edge of the Malari mask as well.

As for the white powder found in vessels at Quta: the broad, shallow form of some of these vessels is not of the type normally used to store liquids. If milk contains even a modicum of fat, it will not remain white in color for long, but it will discolor and through bacterial action it will be chemically transformed and may all but disappear. Even pure milk serum (whey) tends to darken with age and if deposited as a liquid, it will usually dehydrate as a granular mass, not as a fine white powder.

Fig. 7. The golden burial mask discovered in a Quta burial, Guge, TAR. From the presentation of Lin Linhui

Fig. 8. Ceramics, arrowhead and other objects from tomb M1, Quta, Guge, TAR. Of special interest to us is the vase with the spout, which is directly comparable to those discovered in Malari on the opposite side of the Himalayan range (see fig. 6). From the presentation of Lin Linhui

Fig. 9. A copper alloy talisman in the form of three-tiered ceremonial structure with bulbous top. Protohistoric period or early historic period. Private collection

Fig. 10. A rock carving of a similar style ceremonial structure found in Ruthok. Protohistoric period

- Dorji Penjore (The centre for Bhutan Studies): Constructing prehistory in Bhutan through archaeological evidence

This presentation by Mr. Dorji Penjore provided a much needed overview of the state of archaeological research in Bhutan. He explained that archaeological evidence for prehistory in Bhutan is disappearing due to natural and anthropogenic forces. Buddhism also acted to reinterpret the distant past, obscuring the early cultural heritage of Bhutan. Stone tools chanced upon in fields are thought to be ‘iron’ from the sky, the weapons of the gods. They are collected to use as talismans. Mr. Dorji Penjore on typological grounds dates one stone adze to 2000–1500 BCE. Stone pillars are found at monasteries, in the mountains and as border markers. At the Nabje temple, a pillar is thought to have been erected by Guru Rinpoche (8th century CE), when he brokered a peace deal between two warring kings. Mr. Dorji Penjore believes that some of these pillars are of prehistoric origins. Many old bowl-shaped concavities in boulders were used for grinding.

The 200 m long Drapham Dzong in Bumthang (circa 1500–1700 CE) was excavated by the Swiss. A tomb at Batapalathang has been dated to 665–980 CE. The Lasay Tsangma castle, according to the oral tradition, was built by the younger brother of Lang Darma (Glang dar-ma, the last emperor of Tibet). Mr. Dorji Penjore sees this site as a good candidate for excavation. At Mazang Daza, a stone-lined tomb was discovered by farmers. It bears some resemblance to other cis-Himalayan tombs. The Bangtsho fortress castle is reputed to have nine underground levels. The first level was excavated by the Bhutanese government but the results were less than fully satisfactory.

The first Bhutanese archaeologist completed his training in 2006. The Bhutanese government would like to conduct more excavations in due course.

My comments: I think it might prove worthwhile if Bhutan carried out a comprehensive inventory of its archaeological assets before too many other precious sites and objects are lost.

- Lu Hongliang (Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University): Transhimalayan interaction in prehistory

Dr. Lu Hongliang explained that his presentation was derived from his dissertation, which he plans to publish. Dr Lu critiqued the so-called three-step model of the peopling of the Tibetan plateau proposed by Dr. Jeffery Brantingham as being regionally biased. This model focuses almost entirely on the Qinghai plateau. Paleolithic hand-axes from Pakistan and Nepal and those found in the TAR may point to other entry points for the human colonization of the Tibetan plateau. Majiayao Neolithic ceramics are not found in Tibet. The Tibetan Neolithic ceramics assemblage is qualitatively different, says Dr. Lu. Dr. Lu also briefly discussed the perforated semi-crescent shaped sickles found in Burzahom (Kashmir), Chusang (central Tibet) and Kharro (eastern Tibet). Birch bark found in the tombs of Gyaling (Rgya-gling, in western Tibet) appears to have come from the south side of the Himalaya, another example of Transhimalayan interaction. Dr. Lu also compared the ceramic vessels found in Gyaling and Mustang with those carved on rocks in Ruthok. He places the bronze dagger discovered in Kharpoche (western Tibet) with those of southwestern China. In conclusion, Dr. Lu matched the standing stones in Asota, Pakistan with those of Upper Tibet. From these various material parallels he postulates western Transhimalayan and Inner Asian links, having to do with trade. Finally, he called for a multidisciplinary project to better understand these links.

My comments: Dr Lu Hongliang’s presentation featured many intriguing parallels over a vast area extending well beyond the Tibetan Plateau. His premise that the peopling of the Tibetan plateau was multidirectional demands careful consideration by all scholars working on such questions. His thesis that the Tibetan Neolithic was not a mere extension of the Majiayao culture also has merit. For too long archaeologists working in the field have disregarded differences in the drive to find similarities in Neolithic ceramic assemblages. Moreover, theories regarding the direction of material culture transfers have often been made without much critical attention to the underlying premises upon which these are based.

Finding similarities in the material cultures of proximate regions is the raw material for further inquiry based on a well defined methodological regimen. Subsequent study could benefit from the devising of systematic comparative criteria applied to a theoretical template that includes models of demic diffusion, acculturation, trading activity, among other processes that may account for material cultural parallels over wide areas. This is a field of research that has gained much ground in Western archaeology in recent years, but a lot still needs to be done to refine the models and to interpret material remains with more precision.

Fig. 11. From the presentation of Lu Hongliang

- Anke Hein (Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles): Movements on the eastern rim of the Tibetan Plateau – The prehistoric Liangshan region as multi-cultural intersection

Ms. Anke Hein’s presentation was focused on the amazing geographic juncture of the Nangzhao plateau, Tibetan Plateau and the meridian ranges of western Sichuan. She furnished participants with an overview of the extremely rich ecological, cultural and archaeological characteristics of this region. Many material cultural commonalities exist in this region’s archaeological record. A variety of causal mechanisms potentially need to be considered in accounting for material analogues. First off, it should be determined whether material cultural parallels are the result of independent development in different geographic centers. Secondly, if interregional contacts are indicated, were they direct or indirect in nature. Direct contacts may include migrations, the temporary movements of people, trade, and emissary gift-giving, among others.

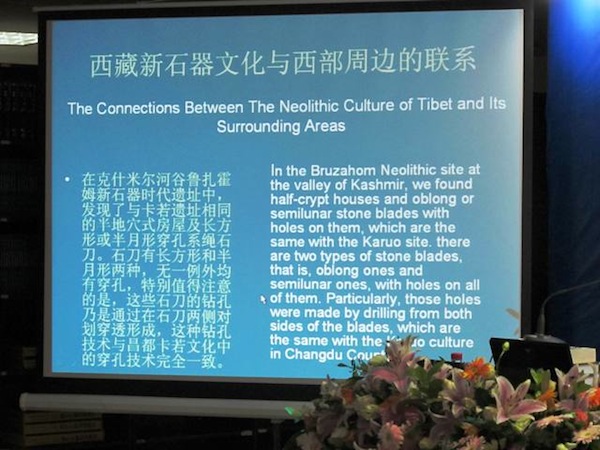

- Shishuo (Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University): The culture of Tibet Neolithic and its connection with surrounding areas

According to Mr. Shishuo, there were four main regional Neolithic centers on the Tibetan plateau: northeast (Majiayao), southeast (Kharro), central (Chos-gong, Chu-shur, Mal-gro gung-dkar) and western (Sdings-zlum). As for Neolithic sites on the Changthang, he connects these to stone monuments and petroglyphs. According to Shishuo, the Changthang Neolithic was probably an integral regional nomadic culture distinct from Majiayao but closely related to Kharro, as determined through a typological survey of microliths.

Mr. Shishuo reports that the Neolithic peoples of the upper Yellow river basin, Kharro, central Tibet, and western Tibet were closely related and that they may have enjoyed systematized relationships. He proposes that the upper Yellow river Neolithic had a heavy influence on Kharro which in turn spread to central Tibet. Also, some Neolithic features of Kashmir spread to central Tibet. He also believes that certain Kashmir Neolithic traits originated in eastern Tibet. To illustrate his ideas, Shishuo compared the various ceramic, microlith, stone mace, and semi-crescent adze assemblages.

My comments: It is essential that Mr Shishuo’s hypotheses (many of which were borrowed from earlier contributions to the field) and other notions about the Tibetan Neolithic are tested with much greater rigor. This is an exciting project that could engage a new generation of archaeologists. I should also note that to date not one rock art or megalithic site in the Changthang has been securely dated to the Neolithic.

Fig. 12. From the presentation of Shishou

- Yidilisi Abuduresule (Xinjiang Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology): The Xiaohe culture and the recent development of its multi-disciplinary research

Dr. Yidilisi Abuduresule provided us with an update of Bronze Age and Iron Age discoveries in Xinjiang, complete with many spectacular photographs. In 2008, a cemetery was excavated at Keliya in the Taklamakan, significantly extending the scope of the Xiaohe culture.

Fig. 13. From the presentation of Yidilisi Abuduresule