October 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another enlivening Flight of the Khyung! This month’s issue and those to follow will present some of the latest archaeological discoveries in Tibet. See here for the first time images of an incredible cave sanctuary. Located in the heart of the Changthang, Tibet’s northern plains, this ancient religious refuge is hidden in a maze of canyons. Even few local people know of its existence. Thank goodness we had an intrepid driver who dared to go where others would stop dead in their tracks, otherwise it would have been a very long walk there.

On the recently completed Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition III (UTRAE III) I was able to chart three undocumented cave sanctuaries of much visual appeal. These long forgotten archaeological monuments afford us new insights into the introduction of Buddhist traditions in Tibet.

I was led to these highly remote sites by a Tibetan friend who lives in the area. Our past joint explorations whetted his appetite to know more about the early history of the region. Although a devout Buddhist, my friend has taken an interest in the Zhang Zhung kingdom and has combed local gorges looking for signs of ancient habitation. His reconnaissance made possible the documenting of enchanting places of ancient worship.

A new archaeological discovery in Upper Tibet: Early encounters between Buddhism and the indigenous cults

Historical background

The triumph of Buddhism (particularly its Indian tantric variant) in Tibet is a major theme in the religious histories (chos-’byung) of that country. It is traditionally held that through the efforts of the so-called Dharma Kings (Chos-rgyal), beginning with King Songtsen Gampo (Srong-btsan sgam-po, died circa 649 CE), and that of great sages and mystics such as Guru Rinpoche and Shantarakshita, Buddhism gradually came to prevail over preexisting religions known traditionally as ‘Bon’. An inverse perspective on this transformation comes from the later religion, also known as Bon, and its historical texts (bon-’byung), which chronicle the persecution of the doctrine and the extraordinary efforts made to save it for posterity. Both sources agree, nonetheless, that the Buddhacization of Tibet was a relentless and contentious affair some centuries in the making. According to Bon texts, a major watershed occurred in the 780s CE, when King Trisong Deutsen (Khri-srong lde’u-btsan) outlawed the practice of this religion.

With the arrival and spread of Buddhism in Tibet in the 7th to 9th centuries CE, great pressure was exerted upon in situ religious traditions. Perhaps beginning as a mass of disparate religious cults without any overarching ecclesiastic superstructure, that which came to be called Bon increasingly resembled Buddhism in terms of its teachings and organization. The specifics of this metamorphosis, however, are obscure due in large part to built-in biases in Bon and Buddhist religious histories. Bon maintains that it was in possession of sutra, tantra, and other Buddhist-like teachings long before Buddhism appeared in India; thus, it ignores or denies the great intellectual debt it owes the rival religion. Buddhism for its part emphasizes a uniqueness and superiority, hardly acknowledging the great cultural wealth it borrowed from the antecedent religions of Tibet.

Western scholars working over the last century have strove to pinpoint what each religious tradition borrowed from the other. Nevertheless, this is an ongoing project and one still surrounded by a considerable degree of uncertainty. The inherent historical stances taken by Bon and Buddhism have conspired to veil Tibetan religious history and this is not something easily undone or deconstructed. Although there is limited documentary evidence, there is wide agreement among Tibetologists that the encounter between the earlier religious traditions and Buddhism led to assimilation, cross-fertilization, and accommodation on an epic scale. Witness the numerous archaic spirits brought into the Buddhist fold, as well as the practice of many indigenous rites and customs now an integral part of that religion. Bon, particularly its five higher vehicles (’bras-bu’i theg-pa), has come to so resemble the teachings of the Nyingma sect that its due to Buddhism is self-evident.

The give and take between the old religions and Buddhism was an extremely complex phenomena, something the Tibetan literary record very imperfectly and incompletely describes. Fortunately, in addition to the literature, there is archaeology. As regular readers of this newsletter and my print publications will know, conflict between archaic (and hybridized) forms of religion and Buddhism in the early historic period (650–1000 CE) and vestigial period (1000–1250 CE) is substantiated in the inscriptions and rock art of Upper Tibet, with its erasures, palimpsests, and disfigurements. Yet, strife between competing religions is but one side of the coin. Yes, clashes were inevitable as different cultural and philosophical systems went head to head, but out of this came a merging of tradition that would dictate the course of Tibetan religion for another thousand years.

Introduction to the site of Churo (4835 m)

Fig. 1. The rock formation of Churo. This archaeological site occupies the hollow in the middle of the limestone mount. It faces in a southwestern direction, receiving plenty of sunlight. The revetment bounding the front of the site is just visible in the photograph.

Situated in an overhang in the middle of a towering blue and red limestone formation is an ancient sanctuary of significant historical value known as Churo (Chu-ro). It is a privilege to be able to document this site for the first time and to share it with readers all over the world. In addition to rock walls and pictographs, the site boasts three stone and mortar chortens (stupa), a common religious monument. While I have surveyed a number of cave sanctuaries of this type in the central Changthang,* this is the first one found with real chortens. Both the chortens and their pictographic depictions can be dated to the early historic period, and probably more precisely to the imperial period (circa 629–846 CE). Chortens of this age in Upper Tibet are rare and where they do survive they tend to be in much worse physical condition (such as those at what is locally called the monastery of Dpal-rgyas gling, in southwestern Tibet).

* For some of these sites, see Antiquities of Zhang Zhung, vol. 1 (<thlib.org/bellezza>).

Fig. 2. The mouth of the cavern in which forward retaining wall and one of the chortens of the sanctuary can be seen. On the rear wall of the cavern, in the middle of the photograph, two mainly white pictographs of chortens are discernible.

Fig. 3. Overview of Churo. The ruined chortens can be seen on the left side of the image while the structural remains of cliff shelters occupy the right side. Two of the painted chortens are located on the rock face directly above the masonry chorten on the right.

Churo is accessed by ascending approximately 20 m along the steep slopes of the formation. The front of the site is demarcated by a L-shaped revetment (7.4 m and 3.9 m in length).The entrance to the sanctuary was located to the west of the short arm of this L-shaped wall. The revetment is 2 m high on the outer side, forming a level space above it (19.5 m x 11.5 m), about half of which is sheltered by a large overhang in the formation. Along the rear wall of the site are the structural remains of several masonry buildings, now reduced to footings and small wall fragments. These structures appear to have been used for residential purposes, sheltering the occupants of the site from the fierce climate of the region. Perhaps upwards of one dozen people lived and worked among these edifices. The location of the site away from major pastures suggests an elite social purpose, as do the religious monuments and artwork. Given the structural evidence, Churo appears to have functioned as a religious center, one removed from the main spheres of economic life. A religious function is also supported by the existence of many other cave shelters in the region and further afield in the Changthang, which are embellished with red ochre chortens, swastikas and mantras, etc.

Fig. 5. Another rock shelter at the foot of the overhang. Note the stone covered niche at floor level.

The chronological development of Churo is still hypothetical. If indications from other cave sanctuaries in the central Changthang are applicable, it suggests that this site was founded prior to the early historic period, in either the Iron Age (700–100 BCE) or protohistoric period (100 BCE to 620 CE). If so, it means that Churo was constructed by archaic religious cults centuries before it was modified with chortens. That such cave sanctuaries were the province of archaic cults is demonstrated in the frequent painting of counterclockwise swastikas in them. Moreover, pictographs of chortens, religious masters, and other subjects at these sites have the appearance of being a more recent (early historic period) addition due to their improvised or supplementary placement. Finally, cave shelters, especially in the gorge country of the Changthang, constitute the original nuclei of sedentary settlement. Nevertheless, in the absence of chronometric data, the possibility that some of these cave sanctuaries were established in the early historic period must also be considered.

Architectural and artistic traits of Churo

The most conspicuous and unusual structural feature of Churo is the trio of chortens planted on the west side of the site, near the edge of the rock formation. Although the chortens, like the sanctuary itself, appear to have belonged to indigenous religious cults, the adoption of this kind of monument shows that Buddhism architectural symbolism exerted a powerful influence upon their development. This implies that these cults became familiar with the enshrining, cosmological, commemorative and protective capabilities assigned chortens by Buddhists, furnishing a precedent for the functions assumed by them in the Bon religion of today. We might speculate that, with the advance of Buddhism in the 7th to 9th centuries CE, even the most remote areas of Upper Tibet came into contact with this religion (the imposition of Buddhism in the region is expressed in a a body of localized Guru Rinpoche occupation myths). Along with the chorten, ideological aspects of Buddhist tradition must have also been introduced into the region at that time. Thus, the construction of chortens probably heralds the embracing of sutrayana and tantric traditions by at least some local groups. In certain cases this initiated fundamental changes that resulted in the creation of the prevailing (Yundrung) Bon religion circa 1000 CE. In other cases, as in much of the Changthang, these changes led to the population assuming a wholly Buddhist identity, 1000 to 1250 CE.

Fig. 8. The chortens were placed upon a wide masonry platform. Despite being highly degraded, it can be seen that this structure is elevated above the cave floor.

Despite centuries of degradation, it is plain to see that the three chortens were built to very precise architectural specifications, a tribute to the adept building skills of the highlanders. That such competent chortens existed in Upper Tibet prior to 1000 CE indicates they were part of a engrained tradition of religious architecture, which spread throughout the region. This is corroborated by rock art in Upper Tibet and its broad spectrum of chorten styles.

Fig. 9. Traces of what appear to be the original embellishment of one of the chortens, using red, yellow and white mineral pigments.

The three chortens are unusual in that they were constructed on top of extremely high masonry bases. The two most westerly chortens are interconnected, another uncommon architectural feature.* These two chortens form the front of a cave chamber. They were constructed primarily with stone blocks but the rounded upper sections (bum-pa) were made with small unbaked mud bricks. There are also larger adobe blocks interlaced in the base and intermediate stage of the twin chortens. From what is visible, the hollow space between the base and upper portions of the structures was spanned with stone corbels, as is also found in some chortens in northwestern Tibet and Ladakh.** The chortens were enrobed in mud plaster and then painted with colorful pigments.

* For another pair of chortens built on a very high base most likely belonging to a non-Buddhist tradition, see Antiquities of Zhang Zhung, vol. 1, site Sa rā, image HTWE58.2.

** For more on these stone corbelled chortens, see the December 2010 issue of Flight of the Khyung.

Although no longer extant, these chortens are liable to have had squat pyramidal spires, like those depicted on the pictographic variants at Churo. The high and narrow profile of the structures is more suited to such a spire rather than an elongated one. The single chorten has a base measuring 1.2 m x 1.2 m. It is now 2.7 m in height. The interconnected base of the twin chortens is 3.4 m in length and it is approximately 3.5 m in height. The south specimen is 90 cm wide at the base and the intermediate stage is 1.2 m wide. The upper stages of the north chorten are of similar dimensions, but the base is somewhat narrower than the one upon which the south chorten sits.

Their non-standard form notwithstanding, the Bon or non-Buddhist identity of the trio of chortens is suggested by the complete lack of Buddhist emblems at the site. There is not even a single inscribed plaque with the mani mantra at Churo, an almost ubiquitous presence at Buddhist sites. Nor does there seem to be any Buddhist folklore attached to Churo. It has been completely erased from the collective memory of local herders. No attempt was made to connect it to Buddhist sites in the region, an unusual state of affairs if the site was of this religious persuasion.

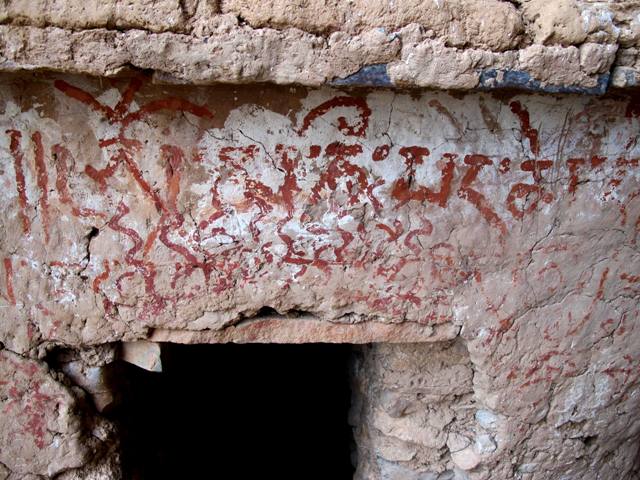

Fig. 10. A mani mantra written in red ochre. This inscription is of significant age (probably 1000–1400 CE), as indicated by the reverse i vowel sign inscribed above the letter na. Also note the wear. The mantra obscures other pigment applications, illustrating its adventitious placement on the chorten. Below the mani mantra is the entranceway to the interior of the chorten. This entranceway has a stone slab lintel.

Fig. 11. At the top of this image a mani mantra was sloppily or hastily written. What appears to be another mani mantra was scrawled below it in the same pale red pigment, which is obscured by a darker red inscription that seems to read: A ru lu… This superimposition may possibly point to a contested ownership of the site.

Fig. 12. A red ochre Lamaist visage drawn on one of the chortens. This figure appears to wear the five-lobed rig-lnga crown of mystic Buddhism. A red ochre conjoined sun and moon (nyi-zla) is also found on one chorten.

Adding to the site’s non-Buddhist or possibly heterodoxic Buddhist aura is sacred graffiti, a few mantras and motifs marking certain portions of the chortens. Written haphazardly, these inscriptions were obviously added at a later date. Some may have been made to bring these monuments within the auspices of Tibetan Buddhism, as it is now known. While I have not identified any patently Bon mantras on the chortens, the manner in which inscriptions are superimposed upon others seems to signal interplay between opposing religious traditions. We might therefore speculate that local inhabitants, sometime after 1000 CE, acted to to repudiate or suppress the antecedent religious affiliations of Churo with their writings.

While the hulks are fairly well preserved, the chortens appear to have been opened up long ago. The looting of these monuments may be related to a non-Buddhist identity. A monastic history indicates that the region around Churo has been dominated by Buddhism since the 11th century CE.

![Fig. 13. A ladder-like structure bisecting the four tiers on the north and east sides of the north chorten. This structure is related to what is called a ‘descent from the god [realm]’ chorten.](http://www.tibetarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Fig.-13.jpg)

Fig. 13. A ladder-like structure bisecting the four tiers on the north and east sides of the north chorten. This structure is related to what is called a ‘descent from the god [realm]’ chorten.

The twin chortens, located in the most westerly part of the site, are ornamented with ladder or stairway projections along the intermediate stage of the structure. The intermediate stage consists of four tiers, which is bisected by eight steps or rungs. Monuments of this general kind came to be called lhabab chorten (lha-babs mchod-rten), one of eight standard types in Tibetan Buddhist tradition. This class of chorten is represented in the rock art of Indus Kohistan and Ladakh, but interestingly, not in the rock art of Upper Tibet. In Ladakh there are also actual stone and mortar lhabab chortens of considerable antiquity, but their form is more in keeping with standard Buddhist iconometry.

Fig. 14. The twin chortens act as a façade to a shallow cave. A portion of the fire-blackened roof of the cave can be seen on the bottom left side of the image. Note the use of stone slabs at each stage of the chorten construction.

Fig. 15. The interior of the cave. The entranceway in the north specimen of the twin chortens is visible in the background. Note the corbelled stone ceiling.

The most peculiar trait of the twin chortens is the manner in which they create a chamber against the west wall of the formation. This chamber (3.5 m x 2 m) does not have standing room: it must have functioned as some kind of sanctum. The fires that once burnt here and the dung covering the floor are evidence of usage by local herders. The entrance (1.2 m x 50 cm) to the chamber is in the north chorten. This chorten overlies the enclosed space, while the south chorten stands in front of it. The north chorten is supported by corbels and bridging stones extending from its forward wall to the rock wall of the formation. That this structure still stands is testament to the durability of this style of construction. By the time the chortens of Churo were founded, Upper Tibetans already had many centuries of experience building all-stone corbelled edifices for both residential and ceremonial use.

Fig. 16. The three main pictographs rising above the stone and mortar chortens, consisting of a stylized handprint (?) and two chortens.

On the rear wall of the overhang suspended about 4 m above the floor are three major pictographs, consisting of what might be a stylized handprint and two chortens. These pictographs were adeptly painted in red ochre and a white pigment (apparently lime). They are very well conceived and executed. That much care went into their creation is reflected in the pargetting of the rock surface with mud/clay. In order to make these pictographs the artists must have used ladders or scaffolding. Placing them high up meant they were inaccessible to the casual visitor. This hard-to-reach position may possibly be related to the existence of contending religious groups accessing Churo. The chortens are approximately 65 cm tall and the handprint-like motif 25 cm in length.

Fig. 17. The red and white chorten on the right. The extremely wide pyramidal spire is an outdated architectural element. In more recent times Tibetans favored narrower spires. A section of the red ochre banner flanking the spire is discernible. Unfortunately none of the finial is intact. In any case, the general outline of this chorten conforms with styles still propagated by the Bonpo. Note the pargetted surface.

Fig. 18. The bichrome chorten on the left. The equilateral triangular spire is clearly an archaic feature. Note the red banner running diagonally from the spire on the left side of the photograph The finial is stylistically intermediate between the sun and moon of the Buddhists and the ‘horns of the bird, sword of the bird’ (bya-ru bya-gri) of the Bonpo. This type of crowning element is commonly seen in Upper Tibetan rock art.

Fig. 19. What may possibly be a handprint was also painted in two contrasting colors. In Tibetan religious tradition, handprints are used to seal a religious quality or blessing on a sacred article (such as a scroll painting). Perhaps a similar function was intended here: the securing of the site for the faction represented by the ‘handprint’.

Above the three pictographs are two small caves. One of them has a hewn threshold of stone and blue sheep horns are suspended in the mouth of the other cave. The function of these caves is not clear. They must have been reached with ladders.

There is another large chorten high up on the west wall of the site but it is in very poor condition and barely recognizable. This pictograph was also painted on a pargetted mud/clay surface. An extremely important image of the 8th century CE Bon saint Tapiritsa (Ta-pi hri-tsa) in a hermitage at Darok Tsho (Da-rog mtsho) is also found on similar pargetting.*

* For a photograph of this painting, click on the website’s photo gallery and go to the archaeology images.

Fig. 21. Near ground level on the rear wall of the overhang, east of the inaccessible pictographs, is another bichrome chorten. This simple tiered structure has a pole-like spire and a finial resembling the Bon ‘horns of the bird, sword of the bird’. This pictograph is 65 cm in height.

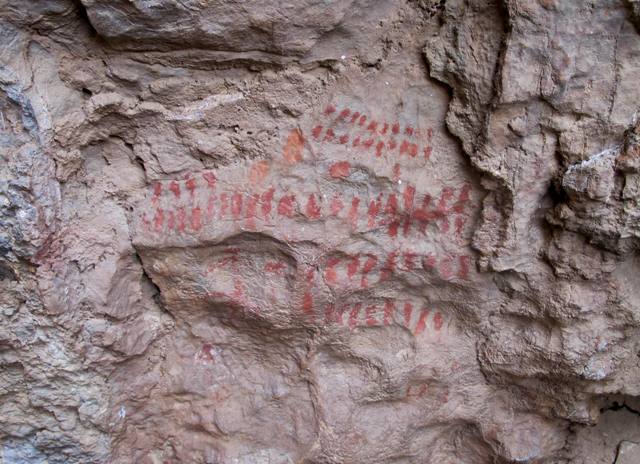

Fig. 22. Also on the rear wall of the overhang, near ground level, are rows of vertical lines or stripes. These may mark a periodic event such as the days or months of someone’s tenure at Churo.

Fig. 23. To the west of the big overhang and chorten is a smaller unmodified cave, which is also perched on the steep slopes of the limestone formation. This cave must have been of some importance because a stone-buttressed path was built to access it, as can be seen in the photograph.

Fig. 24. One of the cubic shrines on the valley floor below the Churo formation. It has been reduced to not much more than a pile of rubble.

There are in fact five cubic shrines in the valley below Churo. They may have had bulbous tops but none are sufficiently well preserved to know for certain. There are no Buddhist remains at any of the shrines. The vestiges of such archaic ceremonial structures are found throughout Upper Tibet. Next year, a special issue of Flight of the Khyung will be devoted to these curious constructions.

Next Month: More ancient cave sanctuaries complete with rock art and other surprises!