March 2012

John Vincent Bellezza

Welcome to another glorious Flight of the Khyung! This month’s newsletter continues to probe the ancient rock art of Upper Tibet, bringing you intriguing compositions and the historical and cultural insights they engender. In last month’s issue, I promised to explore Bactrian camel art with you so let us do just that. Bactrian camels are uncommon in the Upper Tibetan rock art record, having only been documented at four different sites. We will also look at areas where my appraisal of rock art has changed over the years as more and more information about it becomes available.

Bactrian camels up on high

The Bactrian or double-humped camel (Camelus bactrianus) is native to the steppes and deserts of Central Asia. As I understand it, the critically endangered wild Bactrian camel is also found in the Nubra valley of Ladakh, on the northwestern edge of the Tibetan plateau. According to Amy Heller (“The Silver Jug of the Lhasa Jokhang”, www.asianart.com/articles/heller/index.html), wild Bactrian camels also live in the Tsho-ngoen (Mtsho-sngon) region of Amdo. The Bactrian camel is specially adapted to eating snow and ice, an essential capability in the frigid winter conditions of its range. Domesticated Bactrian camels are still widely used as pack animals in the heart of Asia.

Known as ngamong (rnga-mong) in Tibetan, the Bactrian camel has intimate associations with archaic and folk religious traditions. The late great spirit-medium Phowo Lhawang (Pho-bo lha-dbang), who traced his lineage to the 8th century CE, reported that camel hair was braided into protection cords and empowered by the deities of the trance. These cords were supposed to be effective against the predations of all classes of demons. According to the famous circa 11th century CE Bon historical text Drakpa Lingdrak (bsGrags pa gling grags), during the prosecution of [an early form] of the Bon religion in the reign of Tibet’s eighth king, Drigum Tsenpo (Dri-gum btsan-po), Bactrian camels among other animals were to be used to transport sacred texts to safety. The rare Bon ritual text entitled Offerings to the Lha and Purification of the Lha of the Four Types of Little People (Mi’u rigs bzhi lha sel lha mchod) on grammatical grounds can probably be dated to the 11th–13th century. It contains archaic lore and practices that, according to Bon tradition, originated in the mists of prehistory. The origins myth found in the text holds that a ritual to reestablish the balance between humans and the ancestral deities (pho-lha and mo-lha) was first practiced by prehistoric priests known as bon-gshen. These priests are recorded as wearing turbans and capes, and propitiating the ancestral spirits using various offerings including zoomorphic thrones such as that of the Bactrian camel. The Bactrian camel is also associated with Me-ri, a Bon tutelary deity connected to antiquated lore and ritual practices.

Fig. 1. A bowman taking aim at a Bactrian camel and a wild ungulate.

The Bactrian camel can be identified by its long neck and two humps. This deeply carved petroglyph is found in northwestern Tibet, and can be dated to the prehistoric era and perhaps more precisely to the Iron Age (700–100 BCE). This hunting composition suggests that wild Bactrian camels once roamed over the Tibetan plateau south and east of the Nubra valley. If so, this region (around 4500 m elevation) would have constituted the highest altitude habitat of the Bactrian camel in all of its native range. However, the relative rarity of Bactrian camel rock art in northwestern Tibetan suggests either that this animal was never especially common here and/or that it was not of great economic importance.

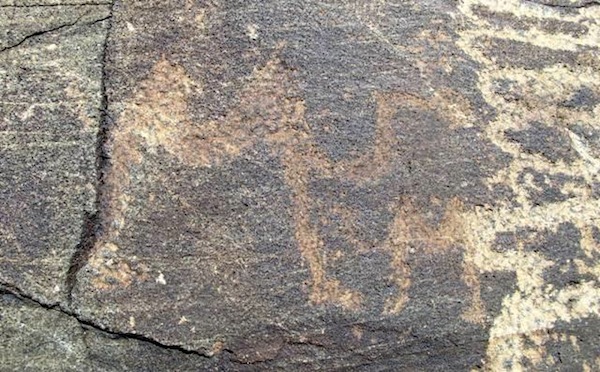

Fig. 2. Although it exhibits very different stylistic and fabrication traits, this Bactrian camel is also located in northwestern Tibet.

The two humps, long neck and head shape are unmistakable physical traits of the species. This Bactrian camel is part of a group of contiguous compositions that includes a fish, stag, boar (?), and several other animals, all of which were lightly pecked (an image of this rock panel was published in Sonam Wangdu’s Art of Tibetan Rock Paintings, Chengdu, 1994). These various wild animal compositions appear to date to the protohistoric period (100 BCE–650 CE). For some dating guidelines see earlier issues of this newsletter or my book Zhang Zhung.

Fig. 3. A large carved chorten (60 cm in height) superimposed on a variety of wild herbivores including five or six Bactrian camels.

This representation of a Buddhist chorten monument (identified by its conjoined sun and moon finial) appears to have been carved no later than the early second millennium CE. This is borne out by its style and the absence of later examples of rock art and inscriptions at this particular site. Like other animals on the same rock panel, the camels seem to represent the wild variety. In some proximate compositions archers on horseback are pursuing animals with bows and arrows. The hunting scenes and Bactrian camels were made by lightly abrading the rock and are now well re-patinated. They all date to before the dawn of the historic era in Tibet.

Fig. 4. A close-up of two Bactrian camels carved to the left of the chorten spire.

The head of the smaller Bactrian camel was obliterated by the chorten etching. The large even toes of the animal are depicted in both specimens, as are its long neck and two humps. Note the very different degrees of re-patination between the camels and chorten. These physical characteristics are liable to reflect many centuries separating the creation of the respective subjects.

Fig. 5. A Bactrian camel on the right side of the graduated base of the chorten.

Part of the chorten carving was superimposed on the rear half of this camel. Palimpsests are very common in Upper Tibet (as they are at many other rock art sites the world over). As I have explained in other publications, the superimposition of Buddhists motifs upon earlier rock art appears to have served several interrelated functions for their makers. These include: 1) the symbolic purification or subjugation of earlier cultural practices encapsulated in rock art such as hunting, 2) the ritual sealing of locales in order to bring them within the territorial fold of Buddhism, 3) recognition of the earlier or ancestral cultural significance of certain rock formations and panels.

Fig. 6. A human figure leading two Bactrian camels.

This highly eroded red ochre pictograph is found on the opposite side of Upper Tibet in the eastern Changthang. This composition by virtue of its camel driver depicts the domesticated variety of the animal. No wild Bactrian camel rock art has been documented in the eastern or central Changthang. This rock art is found along a corridor that saw much Mongol penetration from the 13th century CE onward. Our pictograph however dates to an earlier time. It is probably best placed in the protohistoric period but the scientific means to confirm this attribution are still lacking. The pictograph seems to chronicle a trade route coming from the north, connecting Upper Tibet with steppe regions. It was in the steppes that Bactrian camel domestication reached its highest level of development. If the periodization I have assigned the composition is correct, it seems to signal that communications between the eastern edge of Upper Tibet and the steppic north began long before the 13th century CE. This fits well with other archaeological evidence evincing cultural links between north Inner Asia and Upper Tibet. From our pictograph alone it cannot be determined whether there was widespread usage of Bactrian camels in the Changthang or if this animal was more of a novelty. Of course, it is also possible that the artist was documenting something he or she saw in lower elevation regions of Tibet. Bactrian camels did indeed travel to and live in the Lhasa environs in premodern times, as old black & white photographs portray.

Fig. 7. A close-up of the camel driver.

This figure dons a knee-length robe or caftan. The wide flat shape of the head is suggestive of the wearing of a turban. The vertical line below and just above the waist may possibly depict a style of dress that closed along the center of the body. This kind of closure was known among ancient Tibetans and Central Asians such as the Sogdians. It is also possible however that the vertical line portrays some kind of implement tucked into a sash.

Fig. 8. A red ochre line drawing of a Bactrian camel.

Above this camel are the human figures we concentrated on in last month’s newsletter. What appears to be a yak with a rectangular body was painted over the humps of the camel. The feet of the front legs of the camel were covered up by the painting of another yak. Red ochre running off the anthropomorphic figures has partially obscured the camel as well. I am inclined to see this more realistically rendered example of the animal as dating from the early historic period (650–1000) CE. This is potentially the only Bactrian camel in the rock art of Upper Tibet datable to the historic era.

Inner Asian rock art: more interconnected than I realized earlier

In my book Antiquities of Northern Tibet (2001: 199) I wrote, “…Byang thang rock art forms a separate branch of Eurasian animal art, with its own specific modes of expression, subject matter (sic) and cultural context. The uniqueness of Byang thang rock art is illustrated by the fact that five distinguishing features of steppic art – mascoids, animals in combat, heraldic pairs of carnivores, camels and chariots – are little represented or absent. Perhaps the most defining feature of this regional contrast is the chariot, which had a profound cultural impact on the steppes in the second and first millennium BC, while the Byang thang seems to have been little affected.”

Discoveries made since writing the above words demonstrate that the criteria I used to discern major differences between the rock art traditions of Upper Tibet and north Inner Asia require considerable amendment. As regular readers of this newsletter and my other works will know, in the last decade, I documented mascoids (see December 2011 newsletter), camels (see current) and chariots (see August 2010 and November 2011). As for animals in combat and ‘heraldic’ pairs of carnivores, other distinguishing criteria offered in Antiquities of Northern Tibet, these too must be revised.

Fig. 9. A pair of carnivores attacking what appears to be a wild ungulate. The carnivores (wolves?) are depicted with large upright ears (?) gaping jaws and long tails. Probably Iron Age.

Fig. 10. Here we see three carnivores taking down a large wild ungulate (wild sheep?). The hostile animals are deployed in standard positions for the disposal of prey. One carnivore is shown pulling at the snout, another one attacks from the rear, while the third partner goes for a flank of the unfortunate herbivore. Probably Iron Age.

The two attack scenes depicted above (and a third example) are found on the same panel as several chariots and appear to be thematically and chronologically related. Rather than merely recording the way in which wolves hunt, the carnivore-prey motif may well have had sociocultural value for its makers and intended audience. Qualities of the warrior could be embodied in it; demonstrations of fierceness and fearlessness for instance. These compositions and their ostensible association with chariots seem to have other important implications as well. It appears that trans-regional acculturation (possibly political and economic influences as well) involving Eastern Turkestan to the north or via Ladakh to the west were at play. The chariot and perhaps the strident aggression of animals as well is almost certainly the bequest of steppe-desert peoples who had contact (direct or indirect) with Upper Tibetans. The obvious lines of communications lie in that direction and not through the Himalayan barrier to India. Further comment on the nature of cultural intercourse between the steppes-deserts and plateau will be made in next month’s newsletter.

Although I was wrong about what differentiated Upper Tibetan rock art from that of north Inner Asia, my basic premise remains true: Byang-thang rock art forms a separate branch of Eurasian animal art, with its own specific modes of expression, subject matter and cultural context. The Upper Tibetan examples of even cognate motifs are unique esthetically. While its inhabitants from, say, the late Bronze Age were part of the larger world whirling around the mountains ringing their elevated homeland, theirs was a unique way of life with peculiar cultural, economic and linguistic characteristics.

Another key revision concerning the age of rock art

In my book Antiquities of Upper Tibet (2002: 140), I wrote that the word yak (g.yag) and a yak depiction below it were executed in the same fashion and display the same wear characteristic, thus they the date to the same timeframe (early historic period). I even went so far as to compare this yak with historic era animal petroglyphs and inscriptions from Ladakh studied by Philip Denwood, commenting that they were all stiffly executed and lack the gracefulness and vigor of prehistoric representational art. While this characterization may hold true for the Ladakh examples, it is not true of the Upper Tibetan example. In fact, further scrutiny of the inscription and petroglyph on the UTRAE II shows that they were produced in disparate periods.

We are focusing on this matter because it is an important one. My former interpretation colored an understanding of Upper Tibetan rock art chronology, making me believe in a longstanding anachronistic rock art style for which there is little basis (motifs did indeed often remain the same but the manner in which they were executed changed over time). I still maintain that the word ‘yak’ was written before 1000 or 1100 CE, as the few other inscriptions at the site are of a similar paleography and belong to the Old Tibetan language.

Fig. 11. The inscription and yak under question.

It can be clearly seen in the image that the inscription is less patinated than the depiction of the yak below it. This difference is indicative of some centuries of separation between these respective creations. Moreover, the techniques and probably also the tools used to produce the carvings vary greatly. The letters of the inscription were made using a tool / technique that removed much finer particles of stone with each hit or stroke. The etched lines of the yak are much rougher and deeper, the result of employing a different tool / technique. Perhaps the yak was made using stone tools. In any case, a great cache of microliths was discovered at the site on the UTRAE II. The style of the yak is another important indication of greater antiquity. It was rendered according to an archaic artistic tradition, which appears to have been discontinued before the dawn of the historic era. The animals in the petroglyphs studied by Philip Denwood referred to above do indeed possess the rigidity and perfuntoriness often associated with early historic rock art on the Tibetan Plateau (if I remember correctly: I do not have Denwood’s paper at hand). To compare the yak under inspection with this Ladakhi rock art was my error. However, there is no better time to come clean than the present! In my defense, as weak as it may be, I will say that digital photography has significantly aided the study of rock art. It allows one to take highly detailed images and as many of them as are needed for detailed analyses.

Fig. 12. A close-up of the inscription and the adjoining part of the yak. Variability in the modes of manufacture and ageing requires no further comment. Note that part of the final g of the inscription was carved over the tail of the yak.

Next month: Crucial information on the chronology of ancient civilization in Upper Tibet!