February 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

This Flight of the Khyung glides further across space, keeping you up to date with some of the latest developments in Upper Tibetan cultural history and archaeology. This month we will examine pressing conservation issues as well as ancient rock art. Join me to elevate yourself to the heights of the highest part of the highest plateau on Earth.

A little more on the stone bust featured last month

If you have not already seen the extraordinary stone bust featured in the January newsletter, please do so now. Since posting that newsletter I have consulted with three highly respected Himalayan art experts: Jeff Watt (New York), Dawa Gyaltsen (Kathmandu) and Ian Alsop (Santa Fe). They all confirm that this image is unique by virtue of not falling into any known genre of Himalayan art. Some more conventional paintings and sculptures of Drenpa Namkha depict him with a topknot and/or vertical third eye. Perhaps these prominent iconographic features contributed to Khyungtrul Rinpoche’s identification of the statue as being the likeness of Drenpa Namkha? Pictures of six paintings and statues (made between the 14th and 19th century CE) of this great Bon saint can be found on the Himalayan Art Resources website under the heading “Bon Teacher”: http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=1044:

A tough and rough world: lovely Lake Nam Tsho violated

The limestone caves and formations of Nam Tsho, the giant sky-blue lake situated northwest of Lhasa, are one of the greatest repositories of ancient rock art in all of Tibet. Although pictographs from this exquisitely beautiful region have been published in various places, many of them still await study.

Through books, papers and the internet, I have done my best to bring Lake Nam Tsho’s rock art to the attention of the international community. I plan to continue these efforts, which should culminate in the creation of a comprehensive catalog of Upper Tibetan rock art. Sadly, my publications are the only record of an increasing number of destroyed pictographs and petroglyphs. Due to inappropriate development and the wrong-headed behavior of some individuals, this ancient art is disappearing at an alarming rate. This issue will focus on the significant losses incurred at Nam Tsho identified on the 2012 research mission.

Fig. 1. The stacking of yak dung for fuel use partially obscures a giant red ochre pictograph of an archaic chorten, Lake Nam Tsho. This is just one of many recent impingements on the early artistic heritage of this history laden region. Pictured is the largest pictograph discovered to date in Upper Tibet.

It is stunning to see how much rock art of Nam Tsho has been damaged or entirely destroyed in recent years. Present rates of destruction are greater than anytime in the past. The main factors accounting for this are: 1) the addition of graffiti to rock surfaces, 2) the construction of houses by local people, 3) the development of tourist facilities by commercial interests, and 4) the cutting of new roads around ecologically sensitive headlands. From what I observed less than two months ago, absolutely no measures for the conservation of Lake Nam Tsho’s archaeological heritage have yet been put in place by the authorities.

Fig. 2. The interior of a newly built house at Nam Tsho. The concrete ledge (as well as other structures in the house) have obliterated much rock art.

The biggest threat to ancient rock art and monuments at Nam Tsho comes from local Tibetans themselves. In 2012, a string of houses were built by pastoralists along the south side of the Tashi Do Chung headland, covering up and eradicating rock art and ancient residential remains. I have not yet tallied up the losses but they are very significant indeed. Simply put, archaeologically rich areas around the rocky headland should be protected by the government to curb Tibetans from continuing to build there. Houses already constructed in inappropriate places should be dismantled (with compensation paid to the owners), in order to secure what can be salvaged of the ancient rock art.

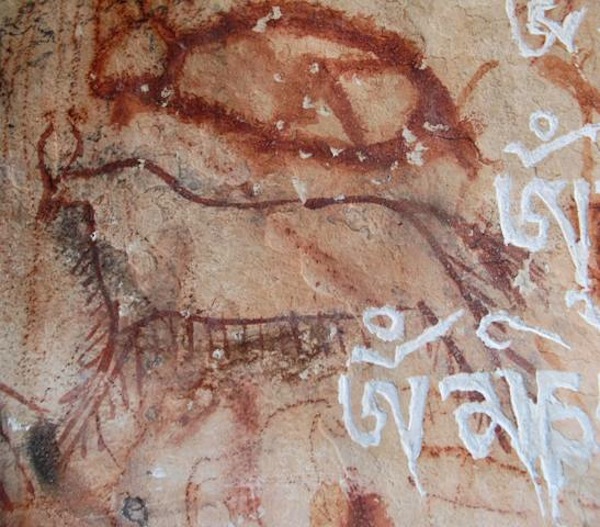

Fig. 3. Note the horse on the upper right side of the image. Along with other drawings, this horse was recently painted over ancient pigment applications.

Fig. 4. The application of butter to pictographs by pilgrims represents another threat to the rock art of Nam Tsho. It is often believed that pictographs were magically self-formed (rang-byon) in ancient times, as sacred demonstrations of saints and divinities. Butter, a potent solvent, can seriously damage ancient pigment applications and obscure otherwise sound images.

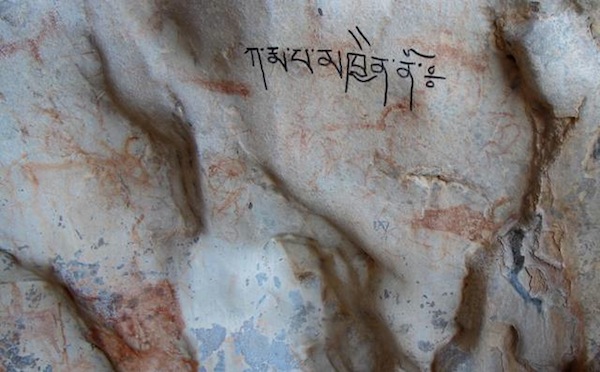

Fig. 5. While it is admirable to see Tibetans expressing their religious sentiments, this recent writing of a mantra (ka rma pa mkhyen no) over ancient art is decidedly unsuitable in its choice of locations.

Fig. 6. Another cave with mantras carved by pilgrims and local residents on rock surfaces hosting ancient art, west side of Lake Nam Tsho. As a result, much art has been disfigured at this site, paintings that only a few years ago were still in excellent condition.

Tibetans have been adding new compositions and inscriptions to the stone surfaces of Nam Tsho for many centuries. In fact, the consequent creation of palimpsests helps in the relative dating of rock art and aids in understanding the religious history of the region. However, never before have new motifs and inscriptions been created so aggressively as in the last few years. Armed with permanent markers and synthetic paints, those seeking to add their contribution to ancient art, harm what should be preserved for posterity.

The Bonpo and Buddhists seem to be mimicking times gone by, with each trying to outdo the other in the sacred caves of Tashi Do and other headlands. This dysfunctional writing and painting competition should be discouraged by fostering an appreciation of the cultural wealth of the region. If Tibetans are harming their own patrimony it is because they do not understand it better. Unfortunately, they have been given little guidance by those appointed to safeguard Tibet’s cultural heritage. A simple awareness program directed at herders could set this right, because most of them highly value their noble past and are seeking opportunities to express this.

Rock art and epigraphy, as precious ancient resources, should be better showcased at the provincial and county levels. This can be effected by adding a module on the conservation of Tibet’s ancient heritage to school curricula, the making of TV documentaries, the holding of academic seminars, the convening of cultural celebrations, etc. Time is of the essence. Events of the last year show that pressure on ancient cultural resources at Nam Tsho (and other regions in Upper Tibet) is intensifying. If nothing is instituted to stop this decline, the situation will only get worse. The initiative however must come from the TAR administration and other concerned government bodies of the PRC.

Fig. 7. The road built around the Tashi Do Chen headland in 2012. This road has degraded the headland and opened it up to further exploitation.

It may be better to close this road, as the area is ecologically sensitive and culturally important and should be left pristine. A patch of dwarf willow forest as well as the last musk deer in the region were found at Tashi Do Chen. The new road passes right through this extremely valuable habitat. Had a proper cultural and environmental assessment of Tashi Do been made, this encroachment may have been avoided. This omission highlights the need for a scientific survey of the area to be undertaken as soon as possible. In this regard, I am happy to help if called upon.

Fig. 8. In 2012, the floor of this sacred cave (one of the last in local folklore to retain a Bon mantle) was paved with stones and a walkway built right to its mouth.

The development of this cave as a touristic site supersedes longstanding pastoral usage by local shepherds. Also, the laying of pavement disturbed and covered up depositions on the cave floor, which could have archaeological value (this cave was an ancient ritual center). Moreover, without a proper conservation plan in place, vandalism of the rock art found inside the cave may increase.

There is certainly no shortage of revenue coming into the region: tourists (Chinese and foreign) must pay 120 yuan (approximately 20 USD) for the privilege of visiting Nam Tsho. I was told by reliable sources that during the summer season an average of three thousand people visit the place each day. Even at other times of the year there is a steady stream of visitors. Simple arithmetic shows that millions are collected each year in revenue. Thus there is no shortage of money that could be used for conservation, if only the will to act existed. In hope of raising ecological and cultural awareness, let me make a few more proposals here that may be of help to those concerned.

In addition to the ticket stub, each visitor to Nam Tsho should be provided with a booklet or brochure furnishing information on the history and culture of the region and spelling out the laws governing archaeological sites. An explanation of what is not permitted, stipulating for instance that local rock art, inscriptions and monuments must not be tampered with or destroyed, is needed. Such a publication could also stimulate an appreciation of the local herders and their age-old way of life. Secondly, a visitors center should be opened at Tashi Do, by far the most popular tourist destination at Nam Tsho. There guests could be further educated and inspired, which would enhance their travel experience and encourage them to pay a return visit.

Tibetans and their Chinese patrons should be able to do a much better job of preserving and propagating the astounding cultural and archaeological heritage of Nam Tsho. Ultimately, the world will serve as a judge of their success.

Of a different form: Tabernacles of the ancients

In the last few years this newsletter has featured a number of archaic shrines and tabernacles found in the rock art record. These depictions never cease to intrigue me simply because we know so little about them. Most are tiered structures that resemble rudimentary chortens of the Buddhists and Bonpo. Nevertheless, some of these representations predate the Lamaist chorten and possess a set of religious functions reflective of the pre-Buddhist cultural environment. While some carved and painted shrines date to the early historic period (650–1000 CE), others appear to be much older.

Some archaic shrines also survive as actual physical remains at ancient residential sites (images and information can be found in the book Zhang Zhung and online at Antiquities of Zhang Zhung: www.thlib.org/bellezza).

Bon textual accounts appear to have nominal correspondence with the archaic shrines of Upper Tibet. As I have noted before, these texts speak of various types of receptacles for deities (lha-rten, gsas-mkhar, rten-mkhar), which are purported to have existed in the prehistoric epoch. They relate tales of tabernacles used as ritual venues for the propitiation of deities such as the Zhang Zhung god Gekhod and his large circle of subsidiary spirits. It is written that propitiatory rituals were carried out in order to subdue enemies and harmful forces. That some rock art shrines had non-Buddhist functions is borne out by the inclusion of counterclockwise swastikas and stars in compositions.

Fig. 9. From left to right: tabernacle (14 cm in height), five-pointed star and two counterclockwise swastikas, eastern Changthang. This vase-like tabernacle has a high pedestal and a half circle midsection connected by a narrow neck to a broad top, which is surmounted by three protuberances. It probably dates to the early historic period, as a minor inscription found nearby exhibiting similar pigment and wear qualities indicates.

Fig. 10. Two archaic tabernacles or shrines discovered in December 2012, eastern Changthang. Note the three-pointed finial resting on the bulbous midsection. These pictographs are small in size and highly worn. The rock on which they were painted has a rough texture, which seems to have limited how much pigment could be applied as well as making the pictographs more susceptible to erosion. See individual images below.

Fig. 11. A close-up of the upper specimen in Figure 10. The prominent tricuspidate finial rests upon a base consisting of two or three tiers. Much of the pigmentation of this pictograph (5 cm in height) has been ablated and has browned as well. The style of the depicted object and its physical condition are indicative of considerable age. It dates either to the protohistoric period (100 BCE to 600 CE) or to the early historic period.

Fig. 12. A close-up of the lower specimen in Figure 10 digitally enhanced to bring out details. The base is made up of two graduated tiers supporting a midsection that tapers outwards towards the top (like the bumpa of some chortens). The finial (tog) is somewhat blurred but it also appears to have a three-pointed form. This tabernacle dates to the same period as the one above.

In the Bon religion of the last thousand years, the trident-like finial ornamenting chortens is called ‘horns of the bird, sword of the bird’ (bya-ru bya-gri). It is popularly said that nothing, not even birds, can land on the sharp points, a sign of the chorten’s exalted nature. The precursor of the horns of the ‘bird, sword of the bird’ is the tricuspidate vertices of archaic shrines, such as the examples under examination in this newsletter. It must be stressed that the Bon and archaic finials do not necessarily share the the same symbolism. With the domination of Buddhism and Buddhist-inspired religious traditions a millennium ago much changed in Tibet. Thus we cannot expect textual and popular interpretations of religious architecture to explain that of a previous age with perfect fidelity. Nonetheless, given the manifold historical continuities present in Tibetan culture, certain ideological and symbolic links can be found. Pinpointing these in each individual case however is very difficult to say the least.

Fig. 13. Another early tabernacle or ritual object (right) that in design is very similar to the specimen in Figure 9. It too has a prominent three-pointed top (connected to a splayed neck) that sits on a wide tablature. The semicircular midsection is supported by a narrow stem attached to a broad foot. Also like in Figure 9, a counterclockwise swastika and a five-pointed star were drawn as part of the composition. This image was taken in 2000 and still remains the only one I possess of this pictograph. Unfortunately, the photograph is slightly of focus, which prompted me to create a black & white copy of it for the book Antiquities of Upper Tibet (Adroit: 2002).

The ubiquitous presence of shrines at rock art sites dating to the protohistoric and early historic periods suggests that they once played a major role in the religious architecture of Upper Tibet. These appear in a surprisingly wide array of styles and were produced using different carving and painting techniques. The extant stone and mortar examples strengthen the impression that they were once widespread. The tiered construction of the archaic shrines is most noteworthy. This layering may have symbolized the five elements or the three vertical realms of the cosmos, as held in more recent conceptions of tabernacular monuments. In addition to Buddhist architectural influences coming from northern India, the Tibetan chortens of today owe their structural inspiration to the archaic shrines. They both possess graduated bases and rounded midsections. As noted by the famous Tibetan scholar Gedun Choephel, these monuments differ significantly from the stupas built in ancient India.

Next month: more recent discoveries!