September 2013

John Vincent Bellezza

Get ready for take off with another Flight of the Khyung! This month we jet between Mongolia and the High Plateau to regale you with stories of the present day and inform readers about the distant past. There is also a feature from my old journals set in northernmost Pakistan. So without further adieu, let’s begin with the recent symposium on Tibetan studies.

The IATS XIII in Ulan Bator

The Internal Association of Tibetan Studies (IATS) conference was held in Ulan Bator, Mongolia, during the last week of July. This was the 13th such convocation of worldwide experts on various facets of Tibet. These meetings are ordinarily held every three years. I was not planning to attend this year’s gathering of the great and the good in Tibetan studies, as I had other travel plans. However, just a few days before the conference was to begin, my plans changed and monies to attend the conference suddenly manifested. Although this might seem like magic, my attendance at the IATS XIII conference was made possible by the Lumbini International Research Institute, the premier educational facility established at the birthplace of the Buddha. Thanks to the efforts and generosity of the managing director of LIRI, Dr. Christoph Cueppers, I soon found myself in Mongolia among some 500 peers. I am most obliged to LIRI and Christoph Cueppers for enabling me to deliver a paper at the conference and for the valuable opportunity to meet and exchange with other scholars, some of whom I have known for years.

I also want heartily thank Professors Charles Ramble (then President of the IATS) and Hildegaard Diemberger (Chief Secretary of the IATS), who not only permitted me to attend the conference at the last minute, but also helped me get comfortably settled in Ulan Bator.

While making the transfer from Beijing, I ran into Frederique Darragon, a dear friend who happened to be waiting for the same flight to Ulan Bator. Frederique treated me to a big lunch in the Beijing airport (I am always ready to eat when the chance presents itself), and we chatted about our work and plans.

Frederique and I were on an architectural panel convened by Dr. Hubert Feiglstorfer, and both our talks were very well received. I spoke about prospects for the conservation of a handful of pre-Buddhist temples in Upper Tibet, which are still relatively intact. I also prepared a second paper on ideological differences between the pre-Buddhist sekhar and Buddhist gonpa, as reflected in their respective architectural styles and locations, but hardly needed it. Frederique Darragon discoursed on the towers of eastern Tibet, a stunning and diverse group of enigmatic structures.

The IATS conferences are rather hectic affairs with many panels being held concurrently. One has to make hard and quick decisions about which ones to attend. There is no time between lectures, which are organized promptly on the half hour, so one must literally race between venues. The colloquium was convened at the National University of Mongolia. The Mongols did an excellent job of organizing the event and were exquisite hosts in every way. For me this will be one of the most memorable IATS conferences ever.

There were many high quality presentations given by scholars at the IATS gathering. For one thing, I was struck by the maturing of economic development studies in Tibet. There are many ways to say something, but to find the most skillful can be a formidable challenge. The greatest textual discovery announced at the conference is that of a circa 12th century CE chronicle of the kings (rgyal-rabs) text from western Tibet, the subject of doctoral research by my friend David Pritzker. I was also much impressed by a paper given on the acoustical qualities of sacred sites by the Mongolianist, initiated shaman and accomplished poet, S. Magsarjav. In the very last session of the conference, Professor Robbie Barnett (another old comrade) regaled a big group of us with Chinese movie clips about Tibet, masterfully demonstrating how this film genre has developed over the last six decades. At a special plenary session, other friends of mine, Dr. Alex Gardner and Ms. Asha Kaufman, introduced the important website of Tibetan biographies, The Treasury of Lives, to conference members. For this key Tibetological resource, see http://treasuryoflives.org

I was able to meet quite a few other friends at the IATS XIII conference and attend a number of very fine papers unnoted above, but will not elaborate any further here. It must suffice to say that it was lovely seeing you all in Mongolia, and I earnestly hope that it won’t be another three years before we meet again!

One could observe that most well-known but older names in the field of Tibetology were not present in Mongolia. Generally speaking, there were few attendees over 70 years old, an age above retirement for most people. On the other hand, there were many new faces, as the baton of scholarship gets passed on through the generations. To see young scholars carry on with a tradition of humanistic and scientific inquiry that arose in the Renaissance (its Classical roots notwithstanding) gives me a sense of joy and pride.

The dorje: Symbol par excellence of Tibetan Buddhism

Fig. 1. A red ochre pictograph of the double or crossed dorje, the so-called ritual thunderbolt (approximately 10 cm in height). This pictograph is instantly recognizable, as it contains all the major elements of this holy symbol. The browning and ablation of the pigment indicates that the painting is of significant age. Perhaps, therefore, a date between the 11th and 16th century CE is best indicated for it, but this remains to be verified utilizing scientific means.

It is curious that in Buddhist rock art and among copper alloy talismans known as thokchas (thog-lcags) the crossed thunderbolt (rdo-rje rgya-gram) is seldom found. In fact, the rock art example shown above is the only one to come to light in Upper Tibet. Also, less than a dozen thokchas of this type with a full radial form have been published to date.* It may be that the great technical skill required to produce well-formed, miniature, crossed thunderbolts in metal dissuaded craftsmen from making them in large numbers. That this symbol epitomizes Tibetan Buddhism as no other does may also have played a role in its rarity as an actual three-dimensional, physical object. Perhaps crossed thunderbolt thokchas were considered only appropriate for use by high ranking clerics and sages. However, this symbol abounds in thangka and mural paintings and other Tibetan decorative arts. From what I can gather, the use of crossed thunderbolts in religious art has increased in popularity in recent centuries. It is now even used to decorate a variety of not very sacred objects including t-shirts and trinkets sold to tourists.

* See:

BELLEZZA, J. V. 1998. “Thogchags: Talismans of Tibet” in Arts of Asia, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 44–64. Hong Kong.

John, G. 2006. Tibetische Amulette aus Himmels-Eisen. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Tung-Kuang Lin. 2003. Antique Tibetan Thogchags and Seals. The Art of Tibet: Taipei.

Several simple (single axis) dorjes are known from the rock art record of Upper Tibet, and thousands of this kind of object were cast as thokchas (in various sizes and styles from circa the 7th century CE to around the 17th century CE). The dorje is a sign of the adamantine and perdurable nature of the Buddhist dharma. Seen as indestructible, universal in scope, and beneficial to all, the Buddhist teachings are encapsulated in the dorje. The crossed dorje also has the distinction of being a prime cosmogonic symbol, with the seed of existence first coalescing in this form before giving rise to the universe.

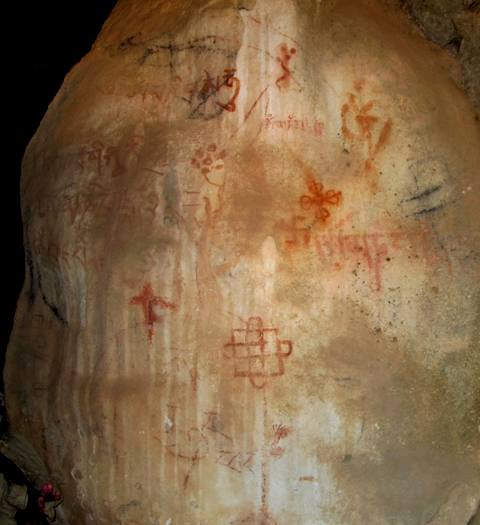

Fig. 2. The rock face upon which the crossed thunderbolt (seen in the upper right quarter of the image) was painted.

This rock face is situated in the rear of a small cave and is marked almost exclusively with red-ochre, Buddhist-period motifs (clockwise swastika and crossed dorje, as well as a flower and a crude cruciform) and mantras (Om, Om mani padme hum, Rigs-gsum mgon-po). The faint markings and lettering in a blue-gray pigment are more recent. The rock surface is rather uneven and not well endowed with that smooth, calcareous veneer favored by pictograph makers in the region. This glossy, light-colored, mineralized coating on the limestone acted as a kind of canvas, absorbing and securely fixing pigments to the stone. The cave does not provide standing room either; one must crouch down to access the rock with the paintings. Thus, this cave was not ideal for the creation of rock art and was largely ignored by pre-Buddhist artists.

It is precisely because of the marginal nature of the cave under study that it seems to have been chosen by Buddhists for their art and mantras: They could claim it as their own without having to navigate around or ritually cope with a proliferation of symbols, inscriptions, and illustrations belonging to the older native religion.

The endless knot may be the only non-Buddhist motif in the cave. In any case, this style of endless knot pictograph is associated with bon motifs and mantras at a few other Upper-Tibetan rock-art sites. It was drawn using a darker red, more cohesive ochre preparation, as were many early pictographs in the region. A non-Buddhist or bon identity is also suggested by the manner in which the stone surface immediately around the endless knot is devoid of art and inscriptions. It is as if Buddhist painters and scribes were attempting to avoid coming into contact with it. The location of the endless knot in the middle of the rock also seems to signal that it predates the patently Buddhist ochre applications. The oldest groups of pictographs are often situated in the middle of the rear wall of caves. This style of endless knot, consisting of nine squares surrounded by four prominent loops, is an early variety of the symbol. I estimate that it was produced sometime between the 8th or 9th century CE and 1300 CE.

Fig. 4. A copper alloy thokcha endless knot of the same style as the pictographic example. Two of the four outer rings have almost entirely worn away. Probably manufactured sometime between 900 and 1400 CE, this popular style talisman must have been used by Tibetans of all sectarian orientations. The endless knot is still highly regarded as an auspicious symbol by both Bonpo and Buddhists. Private collection.

These pictographs are likely to predate the crossed thunderbolt shown above. A clearly prehistoric cruciform was featured in the December 2012 Flight of the Khyung. These motifs encourage us to consider that even the most quintessential of Buddhist symbols, the crossed thunderbolt, may have been influenced by pre-existing forms of indigenous art. Be that as it may, the cruciform motif with bulbous arms predates the arrival of Buddhism in Upper Tibet. Perhaps archaic religious symbology also had an impact on the significance of the crossed thunderbolt, especially as it pertains to its cosmogonic function. This is, to be sure, a speculative statement, but one that should not be dismissed out of hand. We know that the indigenous cultures of Tibet affected Buddhist customs and rituals in a myriad of ways, many of which are still not well documented or understood.

A shadowy figure on the rock

Even in person it is hard to make out this pictograph as it almost blends in with the rock. The entire human figure is depicted. The painting appears to have been made with a chunk of red ochre functioning as a kind of crayon. A survey of pictographs created using this method of drafting indicates that they are of a more recent (historical) origin. Nevertheless, the browning and wear of the pigment suggests that the painting is of considerable age. Another almost life size anthropomorph can be seen in the same area: see December 2008 Flight of the Khyung.

Fig. 7. The head of the anthropomorphic figure. At first glance it appears that this figure may been horned but a closer examination indicates that it is probably not. The identity of this large pictograph is not apparent.

Slicing and dicing the past: More evidence from the rock art record

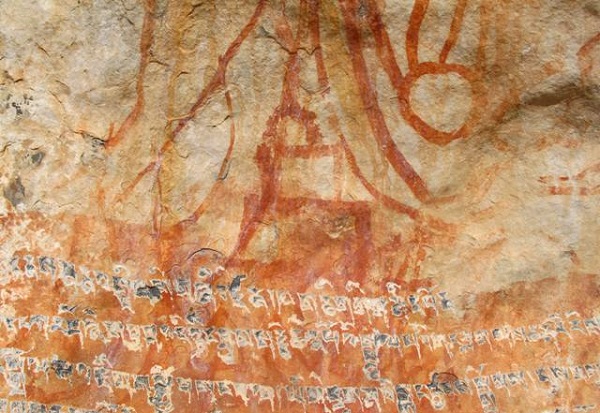

Fig. 8. A sheltered rock face where Buddhist prayers were written on and around earlier rock art.

A mani mantra was boldly scrawled (upper left side of image), probably to secure this location for Vajrayana Buddhism. To its right is another mani mantra and a few other letters. Below and to the left of the big mani mantra is an older inscription announcing the name of the location, confirming that this site has been endowed with the same toponym for many centuries (more on such inscriptions in a future issue of this newsletter). To the right of the red ochre inscriptions are various pictographs.

A mani mantra was boldly scrawled (upper left side of image), probably to secure this location for Vajrayana Buddhism. To its right is another mani mantra and a few other letters. Below and to the left of the big mani mantra is an older inscription announcing the name of the location, confirming that this site has been endowed with the same toponym for many centuries (more on such inscriptions in a future issue of this newsletter). To the right of the red ochre inscriptions are various pictographs. Inferior to all these pigment applications is a lengthy Buddhist sutra carved into the rock.

Great pains were taken to create a Buddhist shrine or landmark from this lakeside location. About 70 long lines (containing several thousand words) of a Buddhist sutra were finely carved in the middle section of the rock face shown. What appears to have been ochre rock art underneath the sutra has had the effect of tinting some of the letters red. The identification of the submerged rock art is not clear, as it was carved up thousands of times over by the inscribed sutra. The concentrations of pigment residue seem to indicate that there were two or three large vertically aligned pigment applications upon which the inscription was superimposed.

The carving of hundreds of verses of a Buddhist sutra was clearly an act of great religious devotion. Many weeks must have been allotted to this effort. The choice of locations is also telling. The activities of older artists were not allowed to stand at the site, presumably because they were representative of the antecedent religion. The placing of a sutra upon this art reflects the superseding of the old religious regime by the new. It is difficult to see how the Buddhist engravers could have been working without this historical and political notion in mind.

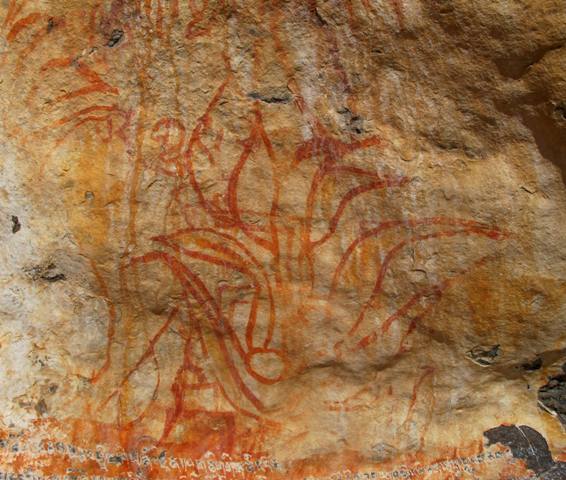

Above the carved inscription is a group of curvilinear motifs that appears to represent flaming jewels (nor-bu me-’bar), albeit in a unique style of depiction. Hampering positive identification is the ablation and running of the pigments, somewhat obscuring the paintings. The relationship between the obliterated pigment applications lying below the carved letters and these pictographs is not clear. In any case, the non-standard style of the flaming jewels recalls pictographs of other auspicious symbols in the region, which are aligned to non-Buddhist or bon religious traditions. These countervailing religious traditions are associated with the 800–1250 CE timeframe. Given the apparent dominance of earlier non-Buddhist cults, this sutra was probably carved subsequent to 1200 CE and the final expelling of ‘Bonpo’ from the region, as testified in Taklung Kagyu documents.

Fig. 10. What appears to be the flaming jewel motif on the right side of the panel. This graceful and quite beautiful red ochre depiction of a sacred symbol important to both Bonpo and Buddhists is juxtaposed against other pictographs. Note the curling tongues of fire rendered as if the rock itself was aflame.

Fig. 11. A chorten or other type of shrine located below the flaming jewel motif illustrated in fig. 10.

This shrine consists of at least three graduated tiers and a rounded top. The uppermost line of the sutra was engraved over the bottom tier of the shrine. This strongly suggests that this shrine was painted by non-Buddhists, as does its elementary form. A coating of red ochre clearly extends below the shrine, the vestiges ostensibly of other pictographs. Perhaps the intact shrine pictograph belonged to the now destroyed compositions found on the stone face below, while the flaming jewels were part of another period of painting. The extant pictographs appear to be too jumbled to have all been a part of an integral composition, suggesting that different time periods and artists may be represented.

Fig. 12. A close-up of the two flaming jewels on the left side of the rock panel. Note the three round jewels in the specimen on the left. Much of the example on the right has vanished with the centuries. The dynamism of this art is a telltale trait of Upper Tibetan non-Buddhist pictographs.

From my archives

Journal, volume 15, October 2, 1990

I chose this selection by chance, randomly opening the stack of photostats to this entry:

I am camped on the approximately 7 km long Shandur Top. The pass is flat and wide and divides District Chitral (NWFP) from District Gilgit (Northern Areas). I think the polo field straddles the very border. Yesterday, when it became apparent that I wasn’t going to get a lift easily, I decided to hike to Shandur and camp out for my birthday. It is sunny but cool this morning. I am very comfortable in my tent enjoying the beauty and tranquility. Camping out in such a place virtually precludes me having to face hassles that might otherwise arise on my birthday. My gift is the wonderful scenery. An azure blue tarn sits outside my tent. Snow capped peaks envelop the broad Shandur Top, whose grasses are a golden color this time of the year. I have plenty of food, so I shouldn’t be facing any problems. This is probably my last hike of the year. I may not get another opportunity like this before returning to America in December. It is very silent up here except for the birdsong. I wonder what kind they are?

Tomorrow I plan to hike to the first village in Chitral, Laspur, and then obtain transport to Mastuj. Hopefully by tomorrow evening I will be at the Mastuj high school seeing my friend of over seven years, the headmaster. What a glorious day. The peace and quiet compensate for having to spend the day alone. I wish the world well. My prayers and thoughts are with my family and friends. By the time I reach Laspur tomorrow I would have hiked approximately 40 miles from Shamaren, an unanticipated addition to this year’s ambulatory explorations. Puffy white clouds linger over the mountaintops, which leads me to believe that it will again turn stormy in the afternoon. My three month visa expires in six days so I will have to be at the Chitral police station by then.

This kind of extensive, flat alpine region is reminiscent of Tibet, and so are the subfreezing overnight temperatures. The monsoon is over, so now come the westerly disturbances. However, in such an arid region as the Hindu Kush, neither weather system brings a lot of precipitation. Shandur Top or thereabouts divides the Gilgit range from the Hindu Raj range. In a few more weeks snow should close the pass for the winter. I have crossed between Chitral and Gilgit four times, all on foot. This however is the first time I have been to Shandur. The name has always symbolized something aboriginal for me. Could it be the name of a forgotten ancient hero or deity? Ancient names often loose their original significance and come to just designate a place. How many times have people replied, it is just a name…

The day passively flows on as the sun arcs to the west. There have been no visitors and I expect none. Several jeeps and pedestrians heading toward Chitral have passed by on the road. I find camps on the crests of watersheds such as this one to be the choicest. The inward and outward views are the clearest. Both the Gilgit and Chitral (Kunar) rivers flow into the Indus; the Gilgit directly at Jagalot and the Chitral indirectly via the Kabul river in Afghanistan. I climbed a small hill and had a fair view of a larger lake to the west. Shandur Top is situated in an east-west direction. I also made out a red roofline visible above a moraine. Could this be the army outpost? I’ll know tomorrow when I cross Shandur. Presently, my camp is on the eastern edge of the flat-topped pass. On a slope above the pass “Chitral Scouts” has been written with painted (?) white rocks in block letters. Each letter must be six feet tall. This form of communication is popular in the Northern Areas. In Pasu and Mastuj, for instance, “Welcome Our Hazir Imam” has been written in a similar fashion. The large white letters contrast well with the dark slopes…

October 3, 1990:

Again, I began hiking early. I cut back to the jeep road and continued at a good pace. The red roofline I spied yesterday belongs to the Chitral Scouts. I think I was supposed to register at the check post, but it was too early for anyone to bother. I stand corrected: the polo ground is next to the outpost. Past the military outpost begins the the largest lake of Shandur, which is at least 2 km long. There are also two other small lakes behind the moraine that the outpost sits on, which I believe are interconnected to the larger lake. All four lakes of Shandur, including the one I was camped on for two nights, drain to the east into the Gilgit watershed. The actual pass is a small crest approximately 1 km beyond the western shores of the big lake. I came to learn later that the actual boundary between Chitral and Gilgit is disputed. Each side claims more of the pass.

From the highest point of Shandur Top the road drops into a narrow valley that leads to the village of Laspur. The descent to Laspur is fairly steep and must constitute a couple thousand vertical feet. I followed an older more direct trail to Laspur. I did not see any opportunity to eat in Laspur without soliciting for it, so I ate a couple handfuls of dried fruit and moved on. This is the beauty of an itinerant lifestyle: If you find yourself in a less than conducive environment you pack up and leave. I climbed atop a large boulder by the roadside a couple kilometers out of the village. I was lost in recollection when a tractor pulling a trailer came by. Without hesitation it stopped for me. For several hours I would endure a bone-jarring 10 km per hour ride to Mastuj. We passed through the villages of Baleen and Bok before stopping in Harchin to offload sacks of dung collected on Shandur. We also had a small meal, which was very much needed, as I had walked ten miles this morning on an empty stomach. I alighted from the tractor above the Mastuj high school…