January 2011

John Vincent Bellezza

A Happy New Year to all of you! The wintery landscape of the northern hemisphere is no barrier to the Flight of the Khyung delivering its payload of fascinating information about ancient Tibet. This month’s issue focuses on the hoary edifices of Ladakh and on quirky inscriptions discovered in Upper Tibet.

The all-stone corbelled edifices of Ladakh

In Swastika or Eternal Bon historical literature it is claimed that Ladakh was part of the ancient Zhang Zhung kingdom. A king named Nyelo Werya is supposed to have been one of the Zhang Zhung rulers of Ladakh. While the prehistory and early ethnic make-up of this western region are still extremely obscure, the archaeological evidence now coming to the fore is beginning to shed light on these subjects. Both the rock art and monumental records demonstrate that ancient Ladakh and Upper Tibet shared certain cultural affinities. In this newsletter we shall look at common links in residential architecture.

Like Upper Tibet, Ladakh boasts all-stone corbelled residential architecture. Two sites employing this type of elite ancient construction have been positively documented: Nyarma and Stok Mon Khar. The all-stone edifice at Nyarma was first described by the researcher Neil Howard in 1989: “The development of the fortresses of Ladakh c. 950 to c. 1650 AD” in East And West, vol. 39. Nyarma has been resurveyed in greater detail by Quentin Devers, a Ph.D. candidate at the École Pratique des Hautes Études (Paris), whose discoveries also featured in last month’s Flight of the Khyung. On the indication of another researcher, Martin Vernier, Devers is the first to chart the remains of a large ruined fortress built in the archaic manner in Stok. As with many similarly constructed strongholds in Upper Tibet, the Stok castle is attributed to that shadowy ancient tribe known as the Mon. Devers has documented other residential complexes in Ladakh that may also have been raised using stone corbels, bridging stones and sheathing, but most of these structures are too degraded to discern architectonic traits.

While we eagerly await Devers’ doctoral dissertation and his publications to follow, he has graciously given me permission to showcase images of Nyarma and Stok Mon Khar. Those familiar with my work will see that these structures are closely identifiable with examples in Upper Tibet. Professor David Germano of the University of Virginia assures me that we are just about ready to launch the two-volume Antiquities of Zhang Zhung online, so you shall soon have much more comparative material at your fingertips. My friend Mickey Stockwell is proofreading the online version of the text at this time.

Nyarma and Stok Mon Khar demonstrate that the most prominent style of archaic residential architecture in Upper Tibet extended as far west as central Ladakh. As for its occurence further west in Zanskar or in Baltistan to the north, regions Bon claims were once part of the Zhang Zhung kingdom, remains to be determined. In themselves, the carcasses at Nyarma and Stok Mon Khar say little about ancient political affiliations, let alone prove that central Ladakh was once an integral part of Zhang Zhung. Even the nature of cultural connections between central Ladakh and Upper Tibet can only be guessed at, relying on these monuments alone. A style of architecture prevalent in one region could have been borrowed by another without recourse to its linguistic and ethnic make-up. All we can safely say is that in prehistoric and possibly in early historic times, builders in Ladakh and Upper Tibet partook of the same architectural canon. This shared tradition may have developed through trade, invasion and cultural exchange.

Alternatively, it could principally reflect preexisting cultural links between these conterminous regions of the Tibetan Plateau. If we take the oral traditions of Upper Tibet and Ladakh at face value, then, their all-stone corbelled installations were constructed by the same tribe or group of interrelated tribes. This is certainly a plausible scenario but one that will require further physical evidence to sustain. Hopefully, in the next few years we will achieve a better understanding of the cultural basis of highland corbelled architecture. I have not visited Nyarma or Stok Mon Khar. In fact, I have not returned to Ladakh since 1989.

Fig. 1: The ridge-top installation of Nyarma with its Buddhist ceremonial appendages. The original function of the main residential structure is unclear. Clearly an elite structure of some type, the historical roots of its Buddhist associations are not immediately apparent. Like several sites in Upper Tibet, it may possibly be a ‘first diffusion of Buddhism’ (bstan-pa snga-dar) installation dating to the early historical period. Nyarma appears to be most closely comparable to Monlam Dzong (sMon-lam rdzong) in Naktshang (a site studied in Antiquities of Upper Tibet). Photograph by Quentin Devers

Fig. 2: A close-up view of the main edifice at Nyarma. Note the protruding corbels at the intermediate level. They must have been knitted to an extension or dependency immediately to the right of the main edifice, an area that is now an open space enclosed by walls. Photograph by Quentin Devers

Fig. 3: The interior chamber in the main edifice at Nyarma. Note the roof assembly with its corbels, bridging stones and sheathing. Photograph by Quentin Devers

Fig. 4: One portion of Stok Mon Khar. Portions of this extensive facility may have been developed after its original foundation date, as exhibited in alternative modes of construction. Once we have Quentin’s final report we will know better. Note the staggered ramparts in the concave central slope, a defensive bulwark regularly encountered in the archaic fastholds of Upper Tibet. Also note the loopholes in the tall summit structure on the upper right hand side of the image. Such apertures are uncommon in all-stone corbelled citadel architecture of Upper Tibet, as is its circular plan. Photograph by Quentin Devers

Fig. 5: An intact vestibule in Stok Mon Khar showing the all-stone roof assembly. Photograph by Quentin Devers

Fig. 6: A section of Stok Mon Khar with an all-stone floor, as is encountered at certain sites in Upper Tibet. Underneath the stone flooring is a shallow vault, which created a level expanse above the underlying rock formation for the floor. Photograph by Quentin Devers

The magical letter A of Upper Tibet

Over the course of the last 16 years, I have documented numerous ancient inscriptions in Upper Tibet, only a fraction of which have been published thus far. The epigraphy of Upper Tibet is a highly interesting field of study to which I plan to devote more time. In an upcoming rock art project, inscriptions and ciphers play an integral part. In the meantime, let us focus on the first vowel of the Tibetan alphabet, which is none other than the grand letter A. In Buddhist and Bon concepts, the alpha is replete with mystic and doctrinal symbolism. It is a cosmogonic prop, psycho-physical marker, prime mantric syllable, and attribute of deities, in addition to having numerous other esoteric identities.

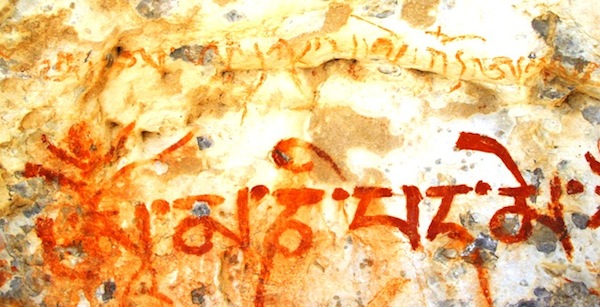

The historical origins of the Tibetan letter A can be pursued through red ochre inscriptions. The calligraphic variability of this one letter is surprisingly rich. In the early historic period, it was inscribed in many different ways, initiating the evolution of forms that remain with us to the present day. The more standard renditions of the letter A dominated by circa 1000 CE, becoming a calligraphic convention. All photos shown below were taken on the Upper Tibet Rock Art Expedition of 2010.

Fig. 7: The holy letter A.

This specimen has been singled out by devotees for treatment with dabs of butter and pieces of paper printed with prayers, warrior spirits and the celestial horse (rlung-rta). It is popularly believed that such inscriptions were magically self-formed (rang-byung) as a demonstration of miraculous religious powers. In reality, this ordinary form of the letter A was almost certainly painted by a Buddhist pilgrim or adept. A timeframe of circa 1000 to 1300 CE seems indicated, the period in which Lamaism emerged victorious in its struggle against the older religious cults of the Tibetan upland. There is much epigraphic evidence of sectarian conflict in this period in the form of defacements, erasures and palimpsests. Note the pigment applications underneath the letter A. These may well be the vestiges of an older non-Buddhist inscription.

Fig. 8: The first five syllables of the six-syllable mantra of the Bodhisattva of compassion, Chenresik (sPyan-ras-gzigs), are visible in this image.

These letters were boldly written in deep red ochre. The initial syllable Om with its superscribed tripartite vowel and consonant sign represents an obsolete calligraphic flourish. This paleographic trait suggests that the mantra was written prior to 1300 CE. As for a terminus a quo, a date before 1000 CE is not likely, because there is little archaeological evidence for a strong Buddhist presence in the Changthang prior to that time. Even more interesting is the upper inscription scribbled in orange-red ochre. This mantra belonged to a non-Buddhist cult (or perhaps more aptly, a pre-Buddhist cult) of Upper Tibet, which can be labeled ‘Bon’ in the most inclusive sense of the word. It reads: “A A A dkar sal le ’od A (followed by two or three largely illegible syllables that should read: yang Om’ ’du)”. This is the first part of the well-known mantra of Kuntu Sangpo (Kun-tu bzang-po), the primordial Buddha of the Great Perfection (Dzokchen, rDzogs-chen) tradition, a profound system of mind training and metaphysical speculation. This sacred ejaculation is supposed to have been first recited by Tonpa Shenrab, the legendary founder of the Eternal Bon religion. It is also worth pointing out that the letter A in Dzokchen represents the primal ground of consciousness. The terminus ad quem of this inscription is circa 1250 CE but it could actually be considerably earlier. In Tibetan literature, Bon and Buddhist Dzokchen are traced to the early historic period (Bonpos hold that it was even practiced in prehistoric times, but this cannot be conclusively established). Despite Kuntu Sangpo also being a deity of Tibetan Buddhism, this non-Buddhist mantra appears to have been deliberately smudged, as probably were other pigment applications underneath and adjacent to Chenresik’s mantra.

Fig. 9: In this image we see an archaic letter A of a non-Buddhist religious orientation upon which the six-syllable Chenresik was carved.

This action of engraving over the letter A has clear symbolic connotations and is an important indicator of historical developments in Upper Tibet. The Buddhists who superseded other religious cults saw their tenure in terms of a victory of Bodhidharma over the heretical non-Buddhist schools, the natural progression from false beliefs to the peerless liberating power of the valid faith.

Fig. 10: I could not resist showing you this inscription although I have already published it in two scholarly papers (see 2000: “Bon Rock Paintings at gNam mtsho: Glimpses of the Ancient Religion of Northern Tibet” in Rock Art Research, vol. 17, no. 1, and 1997: “Notes on Three Series of Unusual Symbols Discovered on the Byang thang” in East and West, vol. 47).

Again, we see what went on to become the first part of the most important Swastika Bon mantra for Kuntu Sangpo: “A A A sa le ’od A”. The next syllable in the standard mantra, yang, was never completed. Probably scrawled sometime between 750 and 1000 CE, this inscription furnishes epigraphic evidence for the existence of early historic period non-Buddhist Dzokchen practitioners in Upper Tibet. Interestingly, the letter A initially written three times was done so in a very non-standard manner, while the final A is instantly recognizable to anyone who reads Tibetan today. These letters were laid down in the same pigment and exhibit the same level of degradation; clearly, the writer was familiar with different styles of calligraphy. In close proximity is another inscription professing the name of the Primordial Buddha and strange anthropomorphous figures that may represent fierce telluric protectors (these are not visible in the image)

Fig. 11: Another archaic letter A of non-Buddhist persuasion.

While such vowels appear to belong to an early historic period chirography, there is a possibility that certain examples may be older. This is not to suggest that Tibetans had a system of writing before the first half of the seventh century CE, but that they may have adopted an Indic letter as a mystic symbol in protohistoric times (I briefly discuss this prospect in Zhang Zhung). So far, I have not discovered even a shred of epigraphic evidence that would permit me to believe Tibetans were literate prior the early historic period.

Fig. 12: Another letter A written in the early historic period or perhaps somewhat earlier. This unusually formed letter is heavily eroded and the pigment has browned significantly, an indication of considerable age.

Fig. 13: Yet another archaic letter A of strange strokes and proportions. Note the faint remains of the subscribed ‘little A’ (a-chung). I do not think this specimen is quite as old as the one depicted in figure 12

Next month: A magnificent copper alloy fibula from western Tibet and other antiquarian wonders for your delight!