September 2011

John Vincent Bellezza

The big event in Chengdu, China

This month’s Flight of the Khyung buzzes in and out of Tibet to provide readers with news from a recent archaeological conference in Chengdu, Sichuan. The International Conference on the Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau was held between August 21 and August 24. It was sponsored by the Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University. Harvard University also provided some sponsorship. Airport transfers, hotel accommodation and meals for participants were provided free of charge by the sponsors. Thank you to all concerned!

Nearly 40 archaeologists from the PRC, USA, India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Germany gave presentations. The topic matter varied greatly as did the methodologies and approaches used. This conference was no doubt a shot in the arm for international collaboration in the field of Tibetan archaeology, giving scholars from diverse backgrounds the opportunity to see what colleagues from other countries and institutions are doing. Hopefully, this will lead to further multidisciplinary international cooperation in Tibet.

The International Conference on the Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau was superbly organized and the events, accommodation and meals were of a high standard. Everything ran like clockwork, a tribute to the hard work of both faculty and students of the Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University. One of the most exciting aspects of the entire conference was to see and meet young Chinese scholars working towards their PhD’s in archaeology. They have much promise and with them archaeological research in Tibet should move away from largely salvage and trophy operations towards hard science approaches to comprehending the distant past. Hopefully, more ethnic Tibetans will make archaeology their calling; at the conference only one Tibetan made a presentation, showing how much still needs to be done to make this field more inclusive. A second Tibetan participant from the Cultural Relics Administration, Lhasa, was invited but at the last minute he could not attend.

The keynote address was delivered by Professor Huo Wei, the director of the Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University. Another important convener was Professor Li Yongxian of the same institute. I have known both of these fine individuals for over a decade. I heartily thank them for inviting me to the conference and for picking up some of my travel expenses. This was the third such Tibet archaeology conference. The first one was held in Beijing in 2003. I was able to attend that one but missed the second one convened in Chengdu a few years later.

Fig. 1. The conference attendees. Photo courtesy of the official conference photographers

The individual presentations

The remainder of this issue will focus on specific presentations. I naturally devote more attention to conference papers that are directly relevant to the Upper Tibetan scene. The length and angle of my coverage is therefore dictated by my personal interests and does not reflect the perceived value of any of the research presented. It was to be three days of presentations packed tightly together in a rather intense show of human knowledge and ingenuity. On the second day of the proceedings there were also lectures after dinner. Each speaker was given 30 minutes including time for questions taken from the audience. Some speakers being fluent in both Chinese and English acted as their own translators.

The conference proceedings are due to be published around the end of 2012. I urge all readers interested in Tibetan archaeology to obtain a copy. I am only able to furnish limited information about a selection of presentations in this newsletter.

- Ofer Bar-Yosef (Dept. of Anthropology, Harvard University): Archaeologically recognizing the interactions between farmers, pastoralists and hunter-gatherers

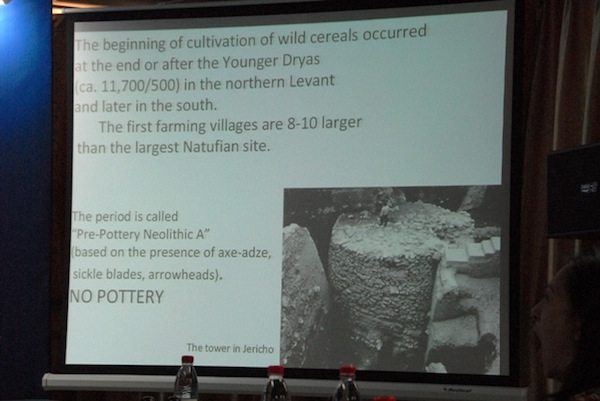

One of the main theses of this first presentation is that in the early Neolithic, agriculturalists began to displace hunter-gatherers by occupying and developing arable lands. Hunters and gathers were subsequently further displaced by early pastoralists. Professor Bar-Yosef illustrated this phenomenon by furnishing paleocultural examples from the Levant, a relatively small but archaeologically rich region. In the Levant, the first cultivation of cereal crops and the first farming villages appeared about 11,500 years ago, very early in the annals of such human innovation. By 8400 BCE, from this cradle of agriculture farming was spreading northward towards Europe and eastward towards the Indus.

In his highly illuminating presentation, Professor Bar-Yosef showed photographs of monumental stone pillars at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. Up to 5.6 m in height, these pillars were carved with spectacular animal designs some 10,000 years ago. These highly competent carvings were executed only using stone tools in a pre-ceramics stage of cultural development. In the question and answer period that followed the talk, we learned that there are several other such sites of carved pillars in Turkey, clearly one of the greatest technological accomplishments of that age. In further discussions, Professor Bar-Yosef observed how his methodologies for determining the displacement of hunter-gatherers might be transferred to Tibetan archaeology, using the example of the Kharro (Mkhar-ro) Neolithic site in Chamdo (Chab-mdo).

Fig. 2. From the presentation of Ofer Bar-Yosef. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

- Bing Su (Kunming Institute of Zoology): Genetic studies of human origins and adaptation of the Tibetan Plateau

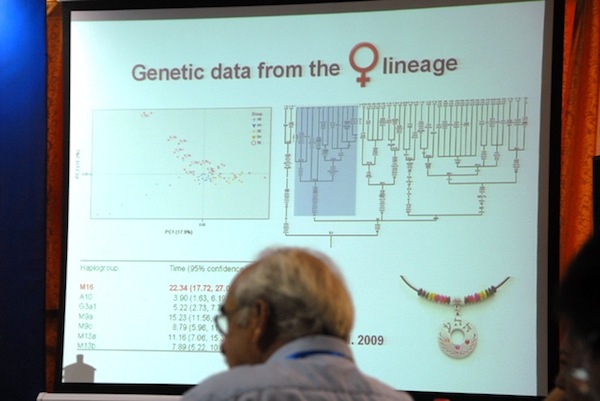

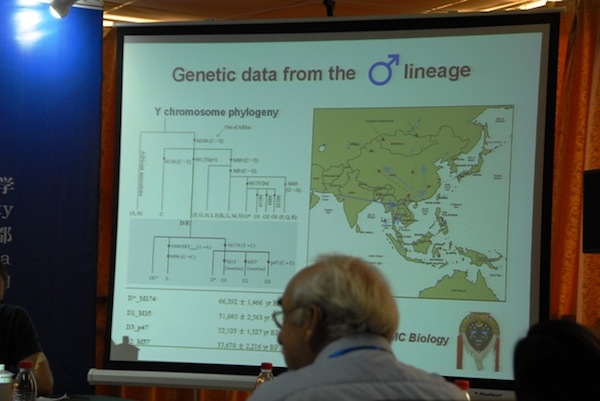

In one of the most innovative presentations made at the conference Professor Su Bing addressed the big questions of when modern humans first occupied the Tibetan plateau and how they developed a genetically based physiological adaptation to living at extremely high altitudes. Professor Su first gave his audience a review of archaeological evidence for the habitation of the Tibetan Plateau in the Paleolithic and Neolithic. He then discussed the current scientific limitations to using modern human genomic data for studies extending back in time. There are 10 million sequenced polymorphisms known in the human genome but chronologically gauging rates of genetic mutation is still problematic, requiring further research and experimentation. Unfortunately, it is relatively rare to have intact fossil genetic data available for analysis, especially in Tibet. The genetic research of Su Bing strongly indicates that the Tibetan and Chinese genomes are indeed distinctive. Tibetans are also relatively genetically distinct from other populations. The Tibetan M16 haplogroup of mitochondrial (maternal) DNA can be traced back about 23,000 years ago. The Y-chromosome (paternal) DNA with its similar phylogeny possesses a haplogroup peculiar to Tibetans known as M57. This set of chromosomes made its appearance on the Tibetan Plateau as much as 37,000 years ago. These haplogroups and other genomic data suggest that the Tibetans are indeed an ancient indigenous population with multiple geographic origins, one that is approximately 30,000 years old. A wide-scale genetic amalgamation also took place 8000 to 10,000 years ago, further diversifying the Tibetan genome.

Tibetans are well adapted against hypoxia due to their elevated resting ventilation, low hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstrictor response, high level of blood oxygen saturation, and low hemoglobin level as compared to acclimatized lowlanders.

Fig. 3. From the presentation of Su Bing. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

Fig. 4. From the presentation of Su Bing. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

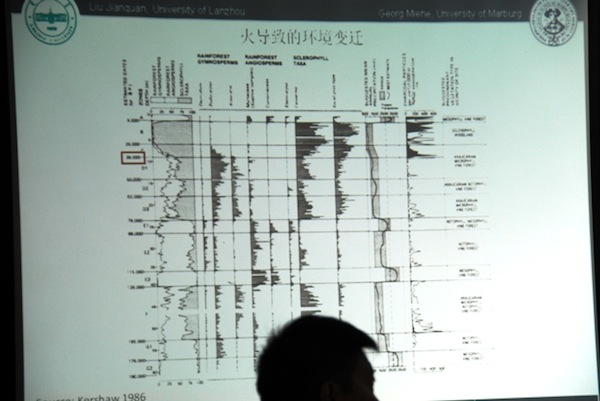

- George Miehe (Faculty of Geography, University of Marburg): How to detect the origin of pastoralism of the Tibetan plateau? An ecologist’s view

Dr. George Miehe, a paleoglaciologist and palynologist, began his presentation by discussing the main constraints to the human occupation of the Tibetan plateau: much more energy is needed to move uphill versus walking on a level surface, water loss from the human body is far greater at high elevations and the onset of menses is progressively delayed the higher one lives. Dr. Miehe observed that large fire-induced changes to the environment can be caused by a relatively small population. In Tibet charcoal found in peat dating back about 9000 years ago, corresponds to the period (early Holocene) in which forests began to be converted to grasslands. George Miehe hypothesizes that humans were the cause. To further his case, he cited the example of relict forests in Tibet. As for Tibetan pastureland, it contains 30% endemic species (an unusually high percentage) and extends from 4000 m to nearly 6000 m, the largest alpine elevational range anywhere in the world. The main floral component of Tibetan pastures is Kobresia pygmaea, which has much of its phtyo-mass below the reach of grazing animals. George Miehe attributes the predominance of this species to long acting grazing pressures. Moreover, ‘weeds’ such as plantago found in Tibetan alpine pastures occur along with grazing. To account for his physical evidence, he suggests that domestic animals of the so-called Neolithic package may have arrived in Tibet far earlier than most archaeologists suppose. Dr. Miehe readily admits though that there is a chronological discrepancy here of around 4000 years. How to close it?

My comments: In discussions with George Miehe, I suggested the possibility of the taming of wild ungulates (such as deer and gazelle) may be responsible for what appear to be grazing-induced changes to the Tibetan landscape. This is not domestication per se, but a human-animal relationship based on intensive interactions that may have included corralling, feeding, sheering, and perhaps riding in certain circumstances. In any case, Old Tibetan language texts speak of the ritual exploitation of wild ungulates for milk and hair. Herds of deer in western Tibet are also mentioned in the Old Tibetan Chronicle.

Fig. 5. From the presentation of George Miehe. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

- Christine Lee (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences): Paleopathological evidence for a warrior lifestyle at the Taojiazhai cemetery, Xining, Qinghai

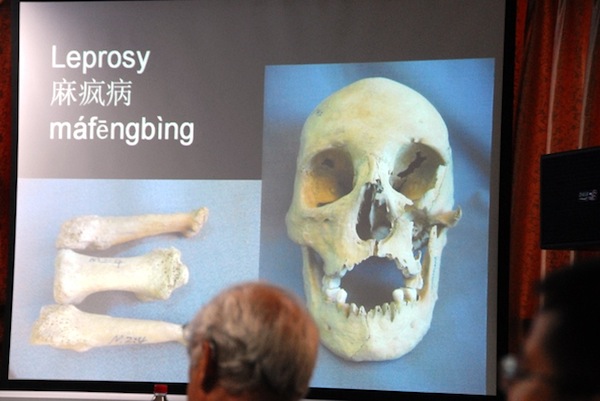

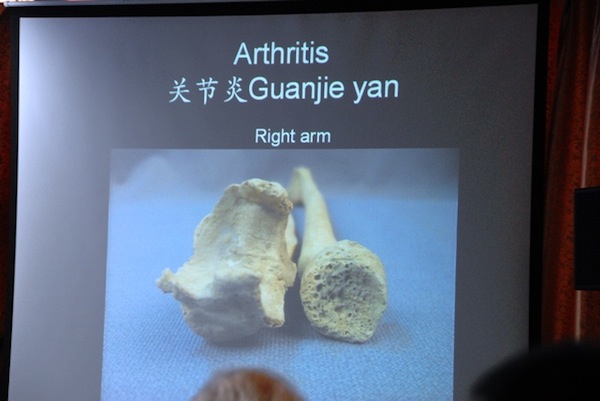

This fascinating talk by Dr. Christine Lee focused on a cemetery of a population related to modern Tibetans found at 2300 m near Xining. Dating to Han times, Dr. Lee’s osteological research shows that those interred at the Taojiazhai cemetery shared familial relationships. Congenital defects were detected in bone remains of the coccyx. Arthritis due to heavy labor (farming, etc.) was widespread. Arthritis in the chest and second finger of the right hand may have been caused by archery. Arthritis in the feet and knees is consistent with heavy walking and carrying loads. At the Taojiazhai cemetery there is much evidence for trauma, accidental and of a military nature. Recurring patterns of trauma to the bones is consistent with organized military operations. A number of victims survived serious injuries, which is indicative of a relatively high standard of medical care. Trepanation among other surgical operations was carried out. Leprosy and TB have also left their telltale marks in the skeletal remains of the cemetery.

My comments: Dr. Christine Lee’s presentation gave participants some inking of what is possible in the field of forensic archaeology. Clearly, the scientific methodologies she relies upon could be introduced on the Tibetan plateau. To date, almost no osteological analyses have been carried out on the many hundreds of corpses unearthed in Tibet. This means that much valuable information about human conditions in ancient Tibet has been lost and is still being lost. Nevertheless, as regards other burials, it is never too late to begin anew.

Fig. 6. From the presentation of Christine Lee. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

Fig. 7. From the presentation of Christine Lee. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

- Wu Xiaohong (School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University): Some issues on chronology in Tibet archaeology

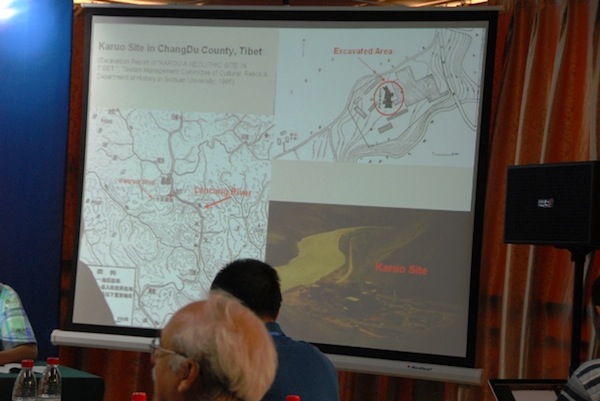

Professor Wu Xiahong has subjected the cultural remains discovered at the Kharro site in eastern Tibet to more stringent chronological testing and analysis. Her findings indicate that certain assumptions about the site (excavated in the 1970s and again in 2002) must be called into question. For example, it cannot be necessarily assumed that all the domiciles with round plans predate those with square plans. Discrepancies also exist in the stratigraphic distribution of radiocarbon dates at Kharro, which are yet to be fully explained.

My comments: Professor Wu Xiahong, head of the National Lab of Quaternary Chronology, has also gently pointed the way forward for Tibetan archaeology. Chronological studies should not be an afterthought, but an integral aspect of any excavation plan. Only by bringing sampling protocols and chronometric testing up to international standards will some of the most basic questions about life in ancient Tibet be answered.

Fig. 8. From the presentation of Wu Xiaohong. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

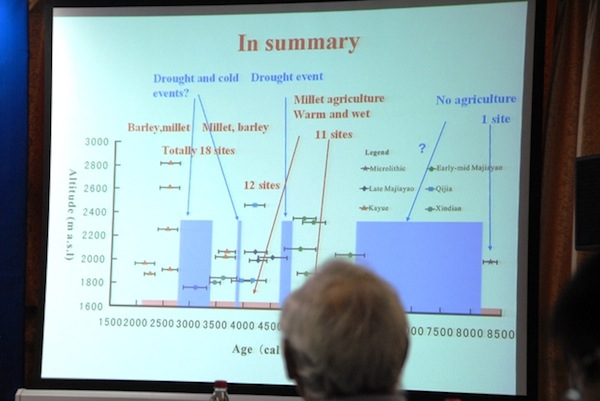

- Jade D’alpoim Guedes (Dept. of Anthropology, Harvard University): Early agriculture on the Tibetan plateau: A review of the archaeobotanical evidence

Archaeobotanical evidence thus far assembled indicates that there were three major introductions of domestic grains to the Tibetan plateau: 1) broom millet and foxtail millet to the eastern plateau circa 3500 BCE, 2) naked barley and wheat to the central plateau no later than 1500 years ago, and 3) hulled barley into western Tibet possibly around 500 BCE. Evidence for millet cultivation comes from the Kharro site. In a later period of occupation (circa 2500 BCE) both types of millet were discovered. Also, pig, bovid, hare, fish, cervid, caprid and gazelle bones were recovered at Kharro. The Neolithic package of millet, pigs and ceramics appears to have been introduced to the site from western China, as part of wider diffusive processes.

Hulled barley, naked barley, wheat, lentils and peas are all domesticates of Near Eastern origins. These crops were being cultivated in the Indus valley by circa 3000 BCE. Wheat and barley reached China by 1700 BCE. These introductions in proximate regions may well have had a direct bearing on Tibet. In the Central Tibetan site of Chugong (Chos-gong), charcoal (not from seeds) has been dated to circa 1370 BCE. The naked barley, foxtail millet, wheat, and peas discovered at this site appear to be from that period. Interestingly, the wheat is a free-threshing variety, as is also found in India, but not in many other places. Ms. D’alpoim Guedes noted that very little zooarchaeological work has been conducted in Tibet, thus the introduction of domestic animals is still an unknown quantity. From the available evidence, she estimates that yaks, sheep, goats, and pigs were first domesticated in Tibet sometime between 1750 and 1000 BCE.

At the Mebrak and Phudzeling sites of upper Mustang, naked barley, lentils, buckwheat, cannabis and other crops were being cultivated between 1000 and 400 BCE. In Kohla, Nepal, free-threshing wheat, barley, oats, buckwheat and foxtail millet were being cultivated, 1385–780 BCE.

It is well established that two-row hulled barley was being cultivated in southwest Asia, circa 8000 BCE. Circa 6500 BCE six-row barley appeared in the same region. Circa 6000 BCE, naked barley cultivation began; this variety is easier to thresh and process, as the spikelets do not adhere to the seeds. Naked barley reached Central Asia in the 1500 to 500 BCE timeframe and was often accompanied by wheat. Naked barley but not hulled barley was found at the Dindun (Sdings-zlum) site in western Tibet, circa 400–100 BCE. At Khardong (Mkhar-gdong), also in western Tibet, both naked and hulled barley seeds have been dated circa 80–340 CE. Given this archaeological evidence, Jade D’alpoim Guedes theorizes that barley cultivation in western Tibet began no later than 500 BCE. She also observed that hulled barley is more resistant to cold and aridity.

My comments: The introduction of hulled barley in western Tibet may be directly related to a pronounced cold and dry period that appears to have set in after 300 BCE. The introduction of domestic grain cultivation in western Tibet, as explicated by Jade D’alpoim Guedes, fits nicely with ancient monumental evidence in the region. The construction of ancient citadels at agricultural enclaves accords well with the archaeobotancial evidence. Perhaps the origins of the agrarian strongholds can even be extended back to 1000 or 800 BCE in western Tibet, pending the acquisition of more chronometric data.

Hopefully, archaeobotany and archaezoology will soon gain ground in Tibet. So much is at stake here, if we are to better understand the development of Tibetan civilization

Fig. 9. From the presentation of Jade D’alpoim Guedes. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

- Lai Zhongping (Luminescence Dating Group, Key Laboratory of Salt Lake Resources and Chemistry): When did prehistoric human beings migrate to the harsh Tibetan plateau: Luminescence and 14C dating results

Dr. Lai Zhongping discussed recent scientific claims for the peopling of the Tibetan plateau, concluding that humans could not have occupied this largest and highest tableland before 13,000 BCE. His conclusions set off a lively debate among the attendees. There are of course those archaeologists who argue for a Middle Paleolithic date regarding the occupation of the Tibetan plateau.

My comments: At this juncture, I belong to the latter camp because an earlier date for the human occupation of the Tibetan plateau seems to best fit the available scientific evidence. During the debate, I noted that even taking Lai Zhongping’s estimates that there existed five to seven times more ice in the last major glacial advance (Younger Dryas event) than at present, this was hardly enough mass to have inundated the Tibetan plateau. An order of magnitude of many tens or hundreds of times more ice would have been needed for that to have occurred. For his part, Dr Mark Aldenderfer defended the OSL dating results for handprints at Chusang. According to Dr. George Miehe, a piece of juniper wood from Lake Dangra may hold an important key to the debate. As the Tibetan juniper genome is marked by long-established hapolotypes, any such analogous genetic material from the Changthang could only have existed if annual average temperatures were not more than 2° centigrade colder, the thermal threshold for juniper growth. There is no altitudinal (warmer) refuge below 4500 m in the Changthang. This Lake Dangra juniper specimen is now with George Miehe and will undergo molecular analysis. Watch this space for the results.

Scientific differences of opinion such as that surrounding human colonization of the Plateau are both stimulating and productive, getting all concerned to reexamine their findings and set out to collect more data.

Fig. 10. Lai Zhongping delivering his lecture. Photo courtesy of the official conference photographers

- Habhibu (Tibet Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology): The condition of archaeological work in Tibet Autonomous Region from 2006 to 2011

Dr. Habhibu announced that an archaeological survey of the TAR was initiated in 2007 and completed this year. He reported that a total of 3013 new sites (including 150 thought to date to the Neolithic) have been discovered, the majority of which are funerary in nature. Dr. Habhibu also presented some archaeological findings from the Mekong river (’Bri-chu) valley of eastern Tibet. Various tombs were recently discovered in this region, which are believed to date from 4500 BCE to 1000 CE. Dr. Habhibu also presented an intriguing ethnographic study of salt collection from the banks of the Mekong river.

My comments: I very much look forward to the publication of the 2007–2011 TAR archaeological survey.

Fig. 11. Habhibu delivering his lecture. Photo courtesy of the official conference photographers

- Li Yongxian (Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University): Regional characteristics of rock art in prehistoric Tibet

Professor Li Yongxian treated us to an overview of rock art discoveries on the Tibetan plateau. He explained that rock art was first discovered in Tibet in Ruthok (Ru-thok) in 1985. Since then some 80 sites have been documented. In recent years, in the Jinsha river valley of southwestern Tibet, 24 rock art sites (20 of which are pictographic) have been discovered. These sites are found at an elevation of 1500–2900 m. Professor Li Yongxian also furnished a typology of Tibetan rock art.

Fig. 12. From the presentation of Li Yongxian. Photo courtesy of Chen Jian

- John Vincent Bellezza (Tibet Center, University of Virginia): Diverting history from oblivion: A plan to conserve the archaeological heritage of Upper Tibet

I was the last speaker on the first day of the presentations. Originally, I was slated to talk about archaeological discoveries made in 2009 and 2010, but I changed my topic to one of the conservation of archaeological sites in Upper Tibet. This is needless to say an extremely urgent and important matter. I reproduce the first paragraph of my paper below:

For 20 years, I have been documenting the pre-Buddhist archaeological resources of Upper Tibet, the vast part of the Tibetan plateau north of the Transhimalaya and west of Central Tibet. This reconnaissance work was carried as part of efforts to elucidate Iron Age (700–100 BCE), protohistoric (100 BCE–650 CE) and early historic (650–1000 CE) civilization in highland Tibet. Through yearly field surveys of early monumental remains in Upper Tibet, it has become evident that manmade threats to archaeological sites have grown alarmingly in recent years. These pressures on what remains of Upper Tibet’s ancient material cultural legacy have four major causes: 1) the robbing of tombs in order to recover marketable artifacts, 2) the pilferage of stones for use in domestic building projects, 3) state-sponsored development projects, and 4) vandalism.

I also gave a presentation on the second evening of the conference. This one introduced the participants to the Antiquities of Zhang Zhung website (thlib.org/bellezza), which was published in July of this year. It would be helpful if other archaeological surveys in Tibet are also systematically compiled and made freely available on the worldwide web.

I also spoke about the need in academic writing for Tibetan place names and other Tibetan proper nouns to be rendered in a phonetic and/or transliterated Tibetan form. As it now stands, most Sinicized toponyms used in Chinese publications are unrecognizable to Tibetans, complicating efforts to identify them. Moreover, as the Tibetan plateau has been traditionally inhabited by Tibetans for thousands of years, using their place names recognizes their tenure and cultural identity. Finally, there is often something in an authentic name; it may encapsulate historical or mythological information pertinent to the site to which it is attached.

Fig. 13. Yours truly delivering his presentation. Photo courtesy of the official conference photographers

Fig. 14. A new retaining wall and parapet wall at Chiu Khar (Byi’u-mkhar). This structure has obliterated the remains of ramparts that belonged to an ancient castle at Byi’u. For more information on this site, see thlib.org/bellezza

Next month: Remarkable archaeological discoveries announced at the International Conference on the Prehistory of the Tibetan Plateau!