June 2010

John Vincent Bellezza

In the annual migration across the Great Himalayan divide, the Flight of the Khyung reaches the Tibetan Plateau. This month’s issue comes to you from Lhasa, the holy city of Buddhism in the center of Tibet. From the state of the environment to an exciting new book and back to the ancient past, there is quite a bit to ponder in this newsletter.

A little side note on climate change

Please skip this section! It is probably not worth your perusal. I admit that it has been added to this brief out of a macabre sense of fascination and concern. There was a blip in the Nepalese media a couple weeks ago. Two species of mosquitoes that carry dengue fever have now been detected in the Kathmandu Valley. In the years to come, if the summers stay this hot, these little rogues could make life distinctly more difficult for the inhabitants of the fair Nepal Mandal.

Thus far, Central Tibet is very dry this year. There has been little rain or snow and some rivers and streams are at alarmingly low levels. Farmers and shepherds are reporting that the water situation is becoming critical. Skip to the Dhauladhar Range, in the Great Western Himalaya, portions of which constitute the wettest climate in the northwestern Subcontinent. This year for the first time in living memory, rivers coming off the mountains went dry. I concede that this might all be a coincidence, a particularly rough year in the normal cycle of climatic events. The trends of the last two decades on both sides of the Himalaya, however, encourage a contrary conclusion. Let me illustrate this with a personal anecdote.

I have just completed the Ganden to Samye trek, an 80 km traipse across the rugged range that separates the Yarlung Tsangpo and Kyichu valleys. I first did this walk in January 1987, losing the companionship of my two fellow trekkers to the -30° C cold. Fortunately they both survived the experience, but not without some health issues. I was left to fend for myself, traversing several frozen waterfalls along the way. In the summer of 1998, I again walked the trail connecting Ganden to Samye via the Shuga La, a distinctly more pleasurable journey. This year the trek was even faster and easier. I traveled with a veteran yak driver from Trubshi village.

One of the most delightful parts of the trek is the jaunt through the forested valley above Samye monastery. In a portion of the valley sheltered from the desiccating winds of the Yarlung Tsangpo valley and endowed with the clouds and moisture that come with higher elevation, survives one of Central Tibet’s last highland forests. This relict forest is found further west than almost any other in Tibet (cis-Himalayan examples notwithstanding). In this sylvan wonderland, junipers dominate the south-facing slopes, while rhododendrons, willow, birch, and other woody species thrive on moister northern slopes.

The ancient juniper at the heart of the sanctum for the forest’s territorial deity, Dorje Yudronma (rDo-rje g.yu-sgron-ma: Adamantine Turquoise Lamp), lives on, but only by the slimmest of margins. Just one portion of this centuries-old sacred tree is still viable (location: 29° 29.525′ / 91° 31.805′ / 4165 m). Its ineluctable fate seems to reflect that of the forest in general. The trees and understory did not seem as luxuriant as I imagined them to be. I had come at different times of the year and forest ecology is certainly not my forte, but a degrading of the environment was palpable. I consulted my 57-year old yak handler, someone who knows that Ganden to Samye route very well. He confirmed that the forest is both receding and thinning.

At least esthetically, if not in substance, youth driving convoys of motorcycles deep into the forest does not help the situation. Nor does their mission: to dig up that fungus-infected caterpillar, a substance that reputedly possesses powerful rejuvenescent qualities, Yarsa Gunbu (dByar-sa dgun-bu). The collection of this bizarre medicine causes much disturbance of the delicate alpine topsoil. Despite this heavy-handed foraging, deforestation is likely to be the main culprit in the debasement of the alpine forest. Climate change is the other prime suspect.

The Tibetan Plateau’s westernmost relict forests are a key environmental indicator in this most sensitive of geographic zones. Their study may determine how the ecology of Central Tibet will fare in the coming years, as well as providing insights into the dynamics of forest loss over the millennia. The life of at least one juniper, Dorje Yudronma’s, hangs in the balance. May she have many more years of verdancy to come!

Murder and mystery in the Himalaya

Recently, I had the pleasure of reading The Oriental Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, by Ted Riccardi, a professor emeritus at Columbia University. First published with Random House in 2003, this very charming book has just been reprinted by Himal Books, Kathmandu. I confess that the murder and mystery genre never grabbed me and I considered Sherlock Holmes a stuffy Victorian light years removed from the realities of the modern world. After reading The Oriental Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, I must reconsider on both counts. The fluency and atmospheric quality of the writing notwithstanding, one of the book’s chief appeals is the way in which Himalayan history and culture are interlarded in tales of intrigue and suspense. Characters include those that speak archaic Himalayan dialects, the great minds of 19th century Oriental studies and British Raj administrators. In the various stories Sherlock Holmes in his ‘lost years’ journeys around the Himalaya in a lethal struggle with the masterminds of international crime. Colorful, erudite and highly entertaining, if you haven’t read this book yet, consider doing so as soon as you can.

The in situ natural mind: A 1000-year old Bon hermitage in Upper Tibet

In 1999, my discovery of a remarkable series of archaeological sites on the north shore of one of the Changthang’s greatest lakes was published in The Tibet Journal (vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 56–90). In addition to the remains of residential structures dating to prehistoric and early historic times, I found an archaeological site of a later period. This was once a Yungdrung Bon hermitage boasting a series of unique paintings and inscriptions. During my reconnaissance in 1997, I recorded its name as Lha-khang dmar-chag (Red-colored Temple), relying on information obtained remotely. More recently, my friends Mariette Wiebenga and Mimi Church informed me that this site is actually known as Sha-ba gdong lha-khang (Deer Face Temple), a place of retreat associated with sNang-bzher lod-po of the 8th century CE (in my 1999 paper, another lakeshore site is identified as Sha-ba gdong lha-khang). Mariette and Mimi are the only other Westerners I know of who have visited this fascinating Bon holy place.

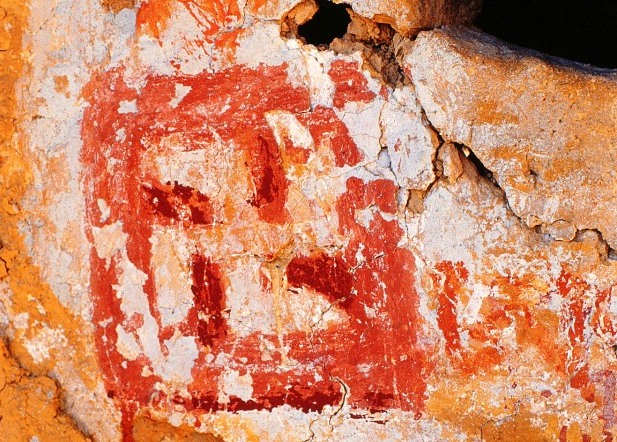

Lhakhang Marchak or Shawa Dong Lhakhang, as you like, consists of several small ruined chapels. They are nestled deep in a cleft punctuating a limestone mount that towers above the scintillating waters of the holy lake. The setting is absolutely spectacular, perfect for the pursuance of Dzogchen, the esoteric religious tradition practiced at Lhakhang Marchak. This is made clear by the lovely image of Ta-pi hri-tsa, on pargetting. Painted circa 1000 to 1250 CE, this extremely rare likeness celebrates the 24th member of the “Zhang Zhung snyan-rgyud”, a tradition of profound mind training perpetuated by a single line of masters. Tapihritsa was the guru of the famous Zhang Zhung sage Nangzher Lödpo. Tapihristsa is said to have first appeared to the incredulous Nangzher Lödpo in the guise of a small boy. In Bon scriptures Nangzher Lödpo is credited with coming to the defense of Zhang Zhung and the Bon religion when they came under attack by Central Tibet’s King Trisong Deutsen. The discovery of Lhakhang Marchak corroborates that upwards of 1000 years ago legends of renowned Dzogchen masters of the 8th century CE were already known in western Tibet.

The main means I used to date Lhakhang Marchak are epigraphic in nature. The hermitage contains a number of inscriptions, mainly stock Bon mantras written in the script and grammar of Classical Tibetan. Some of these inscriptions appear as a kind of sacred graffiti, apparently written after the demise of the facility. There are also inscriptions contemporaneous with the hermitage. The most interesting and unique of these, a collection of still common Bon mantras, was painted in red and blue mineral pigments, each letter and the accompanying symbols studded with tiny shells obtained from the lake below. A masonry plinth or platform in another chapel features favorable auspices (dga’-’khyil), the triple gems and other sacred symbols. This structure may have been used to display tormas (gtor-ma: ritual cakes) and other constituents of Bon liturgical practices.

Clearly those following in the footsteps of Tapihristsa and Nangzher Lödpo occupied and maintained Lhakhang Marchak. In this highly isolated location they must have been left to their own devices. At some point in time and under unknown circumstances, however, the hermitage was abandoned. This is most likely to have occurred in the 12th or 13th centuries CE with the definitive conversion of this remote corner of Tibet to Buddhism under the Kagyüdpa and Sakyapa sects. I hasten to add this is my hypothesis, for nowhere does the historical evolution of Lhakhang Marchak/Shawa Dong Lhakhang appear in written form, at least to my knowledge.

Enjoy the images of the site below. They chronicle a lost but noble chapter in Tibetan history. Fortunately, the Zhang Zhung snyan-rgyud tradition is alive and well. It forms part of the supreme vehicle of Bon, a philosophical and psychological system par excellence.

1. Lha-khang dmar-chag sheltered in a great overhang

2. Lha-khang dmar-chag hermitage

3. Ta-pi hri-tsa, the 8th century Bon mystic, in the attitude of meditation

4. A panel of shell-studded inscriptions and symbols

5. The bee-hive-shaped structure

6. Exterior of temple with shell-studded inscriptions. Note the swastikas, endless knots and other items

7. A plinth decorated in sacred symbols

8. Bon swastika and the Tibetan letter ‘A’ painted in various shades of red ochre and white

9. The great insular sites of Da-rog mtsho, February 2006. Left – Sle-dmar che, center – mTsho-do right – Do dril-bu